Six: Chief Engine Room Artificer T. Dyer, Royal Navy, killed in action on H.M.S. Black Prince at the Battle of Jutland, 1 June 1916 Queen’s South Africa 1899-1902, no clasp (E.R.A. 4 Cl., H.M.S. Terrible) large impressed naming; China 1900, no clasp (E.R.A. 3 Cl., H.M.S. Terrible), these both slightly later issues; 1914-15 Star (269017 C.E.R.A.1, R.N.); British War and Victory Medals (269017 C.E.R.A.1, R.N.); Royal Navy L.S. & G.C., G.V.R., 1st issue (269017 Thomas Dyer, C.E.R.A. 1Cl., H.M.S. Topaze) very fine and better (6) £350-400 Thomas Dyer was born in Alverstoke, Hampshire on 2 September 1874. A Fitter and Turner by occupation, he enlisted into the Royal Navy as an Acting Engine Room Artificer 4th Class on Victory II on 27 April 1897. He served on the 1st class cruiser Terrible, March 1898-October 1902, being confirmed in his rank in July 1898 and promoted to E.R.A. 3rd Class in April 1900. Awarded both the Q.S.A. and China 1900 Medals without clasp - the published roll states that duplicates of both were issued to the recipient. He was advanced to Acting Chief Engine Room Artificer 2nd Class when on Drake in October 1903 and confirmed in that rank in October 1904 when based at Firequeen; he attained the rank of C.E.R.A. 1st Class based at Victory II in 1909. In April 1914 Dyer was posted to the armoured cruiser Black Prince. He was killed in action serving on the ship at the battle of Jutland, 1 June 1916. During the late afternoon and night of 31 May the Black Prince had lost touch with the main fleet. At about 00.15 on 1 June she found herself 1,600 yards from ships of the German 1st Battle Squadron. Illuminated by searchlights, several German battleships then swept her with fire at point blank range. Unable to respond, she burst into flames and four minutes later after a terrific explosion she sank with all hands - 37 officers, 815 ratings and 5 civilians being killed. Dyer being one of the dead was the husband of Isabel Dyer of 244 Chichester Road, North End, Portsmouth. His name was commemorated on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial. Sold with copied service paper. .

186062 Preisdatenbank Los(e) gefunden, die Ihrer Suche entsprechen

186062 Lose gefunden, die zu Ihrer Suche passen. Abonnieren Sie die Preisdatenbank, um sofortigen Zugriff auf alle Dienstleistungen der Preisdatenbank zu haben.

Preisdatenbank abonnieren- Liste

- Galerie

-

186062 Los(e)/Seite

Four: Engineer Captain W. Dawson, Royal Navy Queen’s South Africa 1899-1902, no clasp (Ast. Engr., R.N., H.M.S. Sybille) engraved naming; 1914-15 Star (Eng. Commr., R.N.); British War and Victory Medals (Eng. Commr, R.N.) the first with a few edge nicks, generally very fine and better (4) £500-600 A total of 272 Queen’s South Africa Medals were awarded to the ship’s company of H.M.S. Sybille, 187 of them without clasp. William Dawson was born at New Brompton, Kent in January 1876 and was appointed a probationary Engineer in the Royal Navy in July 1896. Advanced to Assistant Engineer in July 1897, he served in H.M.S. Sybille from October 1900 until she was wrecked in Lambert’s Bay on 16 January 1901, thereby becoming the only Royal Navy ship to be lost during the Boer War. However, unlike four of his fellow officers who were severely reprimanded at the subsequent Court Martial held aboard the Monarch at Simonstown, Dawson was actually commended by his captain for removing and saving the Sybille’s gun-bedplates - he had, in fact, been asleep when the ship struck the reef, but immediately went below and ordered the watertight doors to be shut in the port and starboard engine rooms. Commendably prompt as these actions were, he still considered it dangerous for the engine room staff to remain because of the ship’s severe list to starboard and the resultant risk of the engines being lifted off their beds, in addition to which, there was a growing risk of steam escaping from fractured pipes. The subsequent order for the engine room staff to make for the upper deck was most likely, therefore, prompted by his swift and accurate report of such dangers to his senior - and may well have been responsible for avoiding loss of life. By the outbreak of hostilities in August 1914, he was serving in the rank of Engineer Commander as 1st Assistant to the Chief Engineer at Hong Kong Dockyard, where he had been employed since August 1911. In August 1915, however, he returned to sea with an appointment in the cruiser H.M.S. Blonde, in which ship he was commended for his services when she had to be refloated in August 1916. Then in January 1918, he removed to the Thunderer, in which battleship he remained employed until July 1919, when he returned to Hong Kong to resume his pre-war duties as 1st Assistant at the Dockyard. Placed on the Retired List in the rank of Engineer Captain at his own request in January 1923, Dawson settled in Budleigh Salterton, Devon, where he died in July 1948. Sold with a fine quality portrait photograph, copied service papers, roll extract and other research.

An interesting Second World War and Korean War pilot’s group of eight awarded to Captain P. Maxwell, South African Air Force South African Korea 1950-53 (Lt. P. Maxwell) officially impressed; 1939-45 Star; Italy Star; War Medal; Africa Service Medal, these four all officially impressed (206941 P. Maxwell); U.S.A. Air Medal (Pieter Maxwell); U.N. Korea (Lt. P. Maxwell) officially impressed; South Korean Campaign Medal, unnamed as issued, good very fine (8) £1600-2000 U.S.A. Air Medal - By direction of the President of the United States under provisions of AFR 30-14 and Section VII, General Orders Number 63, Department of the Air Force, 19 September 1950: ‘Lieutenant Pieter Maxwell, South African Air Force. While participating in aerial flights against forces of the enemy in the Korean Campaign, Lieutenant Pieter Maxwell distinguished himself by meritorious achievement. By successfully completing numerous combat missions in F-51 type aircraft from 20 July 1952 to 2 September 1952, he greatly aided the effort of the United Nations Forces and seriously damaged the military potential of the enemy. Lieutenant Maxwell, flying at dangerously low altitudes in adverse weather over enemy-held territory, rocketed, strafed, and bombed enemy supplies, troops, equipment and transportation facilities. By his agressive leadership and courage and by his superior judgement and flying skill, Lieutenant Maxwell has brought great credit upon himself and the United States Air Force. His actions are in keeping with the high traditions of the South African Air Force.’ Peter Maxwell was born in Pretoria, South Africa, on 16 March 1923. He was educated at Pretoria Boys High School and the Pretoria Technical College, metriculating in November 1940. He joined the S.A.A.F. in July 1941 and began training as a pupil pilot. He left for the Middle East in June 1943, was promoted T/Lieut. and W/S/Lieut. in November 1943, and saw service in Italy with Nos. 7 and 41 Squadrons. Lieutenant Peter Maxwell volunteered for service with the S.A.A.F. during the Korean War, leaving South Africa on 19 June 1952. Joining up with No. 2 (Cheetah) Squadron in Korea, he flew many combat missions, often providing cover to the U.S.A.F. 18th Fighter Bomber Wing. The following incident is recorded in South Africans Flying Cheetahs in Korea by Moore and Bagshaw: ‘The Cheetahs also took a hand in the large-scale outpost battles during October and November. The battle for ‘White Horse Hill ‘and ‘Arrowhead ‘raged between 6 and 15 October and cost the communists 10,000 men.. 61 night bombing missions were flown by 2 Squadron (S.A.A.F.).. It was during one of these missions that Peter Maxwell made a forced landing behind the U.N. front lines. He took off in the afternoon of 14 October with three U.S.A.F. pilots from 67 Squadron to support the defenders of ‘White Horse Hill. ‘On reaching the target he found that his radio was unserviceable. The leader indicated that he should circle to the south and stand by. Peter watched the rest of the flight make three passes at a concentration of enemy troops and then decided to follow his American comrades into the next attack. He wanted to join in the action. It was only when committed to the dive that he noticed the gun sight and all other instruments were not working and then the engine cut out. He pulled out of the dive and, after an unsuccessful attempt to restart the engine, he lined up for a landing on a short emergency strip just behind the U.N. front lines. He overshot the strip and the aircraft was damaged beyond repair, but he himself was unhurt.’ After the Korean War, Maxwell decided to remain in the S.A.A.F. (Permanent Force) and received various postings, including the Central Flying School at Dunottar. He was killed in a flying accident in a Harvard at the flying school at Potchefstroom, while attempting a low altitude roll, on 29 June 1965. Sold with comprehensive research and an original photograph of Maxwell receiving his Air Medal on 9 December 1952.

A rare and emotive Second World War clandestine operations M.B.E. group of three awarded to Lieutenant A. W. O. Newton, an ‘F’ Section, S.O.E. agent who was parachuted into France as a saboteur instructor in June 1942, captured in April 1943, and brutally tortured before being sent to Buchenwald: his brother suffered the same fate but both survived to be liberated by the advancing Allies in April 1945 The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, M.B.E. (Military) Member’s 2nd type breast badge, in its Royal Mint case of issue; 1939-45 Star; War Medal 1939-45, together with related G.VI.R. ‘Loyal Service ‘badge and original O.B.E. warrant, this in the name of ‘Alfred Willie Oscar Newton, Lieutenant in Our Army’ and dated 13 August 1945, the medals very fine and better, the warrant torn in several places (Lot) £400-500 M.B.E. London Gazette 30 August 1945. The original recommendation states: ‘This officer was parachuted into France with his brother on 30 June 1942 as a saboteur instructor to a circuit in the unoccupied zone. In this capacity he worked for a period of nine months, throughout which period he showed outstanding courage and devotion to duty. He travelled continuously and organised and trained sabotage cells in various regions, in particular Lyon, St. Etienne and Le Puy. These groups subsequently carried out effective sabotage on enemy industrial installations and railway communications. Newton was arrested in April 1943 with his brother and incarcerated at Fresnes, where he spent over a year in solitary confinement. He was later transferred to Buchenwald concentration camp where he suffered grave hardships. He was liberated in April 1945 when American forces occupied the camp. For his courageous work in the French Resistance and his remarkable endurance during his two years in captivity, it is recommended that he be appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (Military Division).’ No better summary of the wartime story of S.O.E’s famous ‘Twins ‘, Alfred and Henry Newton, maybe found than that published in E. H. Cookridge’s Inside S.O.E.: ‘The two saboteurs selected for the job by Buckmaster [the destruction of the German radio station at St. Assise] were Alfred and Henry Newton, twin sons of a former Lancashire jockey who had been a racing trainer in France and had lived there with his family for many years. The brothers had become well-known on the Continent as variety artistes, ‘The Boorn Twins ‘, performing a comic tap-dancing act. When the Germans invasion came, Alfred and Henry, who had both married French girls, decided to try and bring their families to England. Alfred Newton had three children, Gigi 10, Jimmy 9 and Coco 3. They trecked in night marish conditions along roads crowded with refugees to Penzon in the Vendome. There the men were apprehended by the Vichy police, interned as ‘enemy aliens ‘and put into a works battalion. After many difficulties the twins escaped to Spain, were arrested by Franco’s police and taken to the internment camp at Miranda de Ebro. They were not released until Christmas 1941. At the British Embassy in Madrid they learned that their families had been evacuated from France by the Red Cross and brought to Lisbon for repatriation to Britain. During the sea journey they had all been drowned, when their ship, the Avoceta, was torpedoed in an Atlantic gale on 25 September 1941. By the time the brothers arrived in London they had but a single thought between them - vengeance on the Nazis. They were given an opportunity almost immediately. I know of hardly another case where a rank-and-file agent was directly enrolled with S.O.E. Nearly always the volunteers came from the Forces. But the story of the Newton twins had become known to British Intelligence officers at Gibraltar and was reported to Headquarters in London. When they arrived aboard the destroyer H.M.S. Hesperus in Liverpool, they were taken to a Field Security Officer, given tickets to London and asked to see a Major at the War Office. This officer gave them an address near Baker Street. The address was 6 Orchard Court, Portman Square, and the man who welcolmed them was Major Lewis Gielgud, the chief recruiting officer of the French Section of S.O.E. Henry Newton spoke for them both: ‘Give us a couple of tommy guns and a bunch of hand grenades and we know bloody well what we’re going to do. ‘Major Gielgud had some difficulty in explaining that it was not as simple as that. But he realized that he had two men who would shirk no task, however dangerous or difficult. He decided they were ideal material for training as saboteurs. For several weeks, at Special Training School No. 17 for industrial sabotage at Hertfordshire, the twins were put through their paces. They were circus acrobats and as tough as they come. When the Chiefs of Staff ordered the destruction of St. Assise transmitter, Buckmaster had no doubt whom he wanted for this job. At last the big day came. Peter Churchill was to be dropped ahead of the Newtons, who had become ‘Arthure ‘and ‘Hubert ‘, two French artisans, to conduct them to the German radio station. The signal heralding their arrival to the local reception group was to be: Les durs des durs arrivent (The toughest of the tough are arriving). The target was of the utmost importance. The St. Assise station was used by the German naval command for directing U-boats in the Atlantic. Its destruction would have caused a breakdown in these communications and probably saved the lives of many British and Allied seamen. Many weeks of preparations preceded the despatch of the two saboteurs. The Newton twins were taken to the big S.O.E. radio station at Rugby and shown all over its installation, to learn what they had to look for at St. Assise. A ‘safe house ‘was prepared at Le Pepiniere, eight kilometres from St. Leu, in the vicinity of the German transmitter. R.A.F. reconnaissance aircraft brought back scores of aerial photographs of St. Assise and the twins were briefed for endless hours. On 28 May Buckmaster and Major Guelis, the briefing officer, came to Wanborough Manor with the latest report of the Meteorological Department, which forecast perfect weather. Eventually they all drove to Tempsford airfield. ‘Arthure ‘and ‘Hubert ‘, rigged up in old suits of an authentic French cut, were put aboard a Whitely, with a load of propaganda leaflets from the political Welfare Executive which were to be scattered on the way. But the aircraft developed engine trouble and the S.O.E. men had to be transferred to a Wellington. Just when they were inspecting their parachuting gear, ‘Gerry ‘Morel ran on to the tarmac. ‘The operation is off. Sorry, you’ll have to get out, ‘he told them. The twins were livid.’ However, as confirmed by the activities described in the above recommendation, the ‘Twins ‘were indeed actively employed in France shortly afterwards. Cookridge continues: ‘A few weeks later Alfred and Henry Newton were dropped on another mission - to teach sabotage to Resistance groups in the Lyons area. They were getting into their stride and did some excellent work when, through the betrayal of a V-man, an Alsatian named Robert Alesch who posed as a priest and was known as ‘The Bishop ‘, they were caught by the Gestapo. The twins underwent unspeakable torture at the Gestapo H.Q. at Lyons, at the hands of it notorious commander, S.S. Sturmbann-Fuhrer Barbie and his thugs. They never gave any of their comrades away and spent the last two years of the War at Buchenwald, where they had a miraculous escape from the gallows, and were freed in 1945.’ Robert Alesch was tried and executed after the War.

The rare and important Second World War St. Nazaire raid D.S.C. group of seven awarded to Lieutenant-Commander (E.) W. H. Locke, Royal Navy, who was Warrant Engineer aboard H.M.S. Campbeltown and taken P.O.W. after the loss of M.L. 177 Distinguished Service Cross, G.VI.R., the reverse officially dated ‘1945’; 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; Africa Star; War Medal 1939-45; Korea 1950-53 (Lt. Cdr., R.N.); U.N. Korea, mounted court-style, generally good very fine or better (7) £20,000-25,000 Only 17 Distinguished Service Crosses were awarded for the St. Nazaire raid, the vast majority to men of Coastal Forces, Locke’s award being one of just two to the Campbeltown. D.S.C. London Gazette 11 September 1945: ‘For gallantry, determination and devotion to duty in H.M.S. Campbeltown in the raid on St. Nazaire in March 1942.’ Wilfrid Harry Locke, who was appointed as a Warrant Engineer in October 1941, was placed in charge of the engine-room of the former American four-stacker Campbeltown in early 1942, which ship had been allocated a key role in forthcoming ‘Operation Chariot ‘, namely to ram the southern caisson of the Normandie Dock in St. Nazaire, laden with delayed action explosives, thereby destroying the facility and denying the mighty Tirpitz use of the only suitable dry-dock on the Atlantic coast. Accordingly, over a two week period in March 1942, the Campbeltown was fitted out at Devonport and outwardly altered to resemble a German Mowe-class torpedo boat, while internally she was fitted with a special tank containing four tons of T.N.T. and eight-hour delay fuses which were to be activated two hours before she reached the Normandie Dock. Setting out on her final voyage with the raiding force on 26 March, she took over as Force Leader shortly after midnight on the 28th, when seven and a half miles remained in the run-up the Loire. Finally, at about 0130, with less than two miles to go, the German defences awoke. C. E. Lucas Phillips takes up the story in The Greatest Raid of All: ‘A continuous stream of projectiles of all sorts was now striking the Campbeltown, but so violent was the sound of our own weapons that the ring of bullets on her hull and the crack of small shells was hardly noticed; but when larger shells shook her from stem to stern none could be unaware, and what every survivor was to remember for ever afterwards was the unchecked flow of the darts of red and green tracer flashing and hissing across her deck and the quadruple whistle of the Bofors shells. Bullets penetrated her engine and boiler-rooms, ricocheting from surface to surface like hornets, and Locke, the Warrant Engineer, ordered hands to take cover between the main engines of the condensers, except for the throttle watchkeepers ..’ With 200 yards to go a searchlight fortuitously illuminated the check-point of the lighthouse on the end of the Old Mole, enabling Lieutenant-Commander S. H. Beattie on the Campbeltown’s bridge to correct his aim on the caisson. Having then ploughed through the steel anti-torpedo net, the old four-stacker closed on her collision course at 20 knots, and every man aboard braced himself for the impact. At 0134 the Campbeltown crashed into the gate, rearing up and tearing the bottom out of her bows for nearly 40 feet. Commando assault and demolition parties streamed ashore, while below the sea cocks were opened to ensure the Germans could not remove her before she blew up. As she settled by the stern, Beattie evacuated the crew via M.G.B. 314, and Lieutenant Mark Rodier’s M.L. 177. Locke and Beattie, with some 30 or more of Campbeltown’s crew boarded the latter vessel, and started off down river at 0157 hours. Lucas Phillips continues: ‘The boat was embarassingly overcrowded but Winthrop, Campbeltown’s doctor, helped by Hargreaves, the Torpedo-Gunner, continued to dress and attend to the wounded both above and below deck. Very soon, however, they were picked up again by the searchlights lower down the river and came under fire from Dieckmann’s dangerous 75mm. and 6.6-inch guns. Rodier took evasive action as he was straddled with increasing accuracy. The end came after they had gone some three miles. A shell .. hit the boat on the port side of the engine-room lifting one engine bodily on top of the other and stopping both. Toy, the Flotilla Engineer Officer, went below at once. Beattie left the bridge and went down also. He had no sooner left than another shell hit the bridge direct. Rodier was mortally wounded and died a few minutes afterwards .. The engine room was on fire, burning fiercely, and the sprayer mechanism for fire-fighting had also been put out of action. Toy, who had come up momentarily, at once returned to the blazing compartment but was never seen again. Locke, Campeltown’s Warrant Engineer, was able partially to repair the extinguisher mechanism. The flames amidships divided the crowded ship in two, but the ship’s company continued to fight the fire for some three hours by whatever means available. At length, when all means had failed and the fire had spread throughout the boat, the order to abandon ship was given at about 5 a.m. One Carley raft had been damaged, but few of the wounded ratings were got away on the other, and the remainder of those alive entered the icy water, many of them succumbing to the ordeal. All of Campbeltown’s officers were lost except Beattie and Locke, among those who perished being the brilliant and devoted Tibbets, to whose skill and resourcefulness the epic success of the raid was so much due and whose work was soon to be triumphantly fulfilled.’ Locke and the other survivors had been rounded up by the Germans by 0930 hours, which was expected to be the last possible time for the acid-eating, delayed action fuses in Campbeltown to work. Thus it was with all the more satisfaction that at 1035 hours the British prisoners, gathered together in small groups across the St. Nazaire area, heard the terrific explosion which blew in the caisson and vaporised Campbeltown’s bows. The stern section was swept forward on a great surge of water and carried inside the Normandie Dock where it sank. Thus the main goal of the operation was achieved for a cost of 169 dead and about 200 taken P.O.W., many of them wounded, out of an original raiding force of 611 men. Yet only six of Campbeltown’s gallant crew were eventually decorated, Beattie being awarded the Victoria Cross. For his own part, Locke was incarcerated at Marlag und Milag Nord camp at Tarnstedt, and was not gazetted for his award of the D.S.C. until after being liberated, a distinction that prompted his former ‘Chief ‘, Mountbatten, to write: ‘From my personal knowledge as Chief of Combined Operations, I know how well deserved this recognition is and am delighted to see that the part you played in such a hazardous expedition has been recognised nearly four years afterwards. I hope that you have fully recovered from your captivity and should like to wish you the best of good fortune in the future.’ Locke remained in the Royal Navy after the War, seeing service aboard the Padstow Boy, Jason and the aircraft carrier Indefatigable, and was present in operation off Korea in the Hart as a Lieutenant-Commander (E.). Having then removed to the Bellerophon, he was placed on the Retired List in 1955; sold with a copy of The Art of Jack Russell, with a signed dedication to Locke’s bravery at St. Nazaire.

Family group: The rare and important Second World War St. Nazaire raid D.S.M. group of seven awarded to Chief Engine Room Artificer Harry Howard, Royal Navy, who was responsible for scuttling H.M.S. Campbeltown after she had rammed the dock gate - and fortunate indeed to make his escape in M.G.B. 314 - a story related by him under the title ‘Stand by to Ram ‘in Carl Olsson’s wartime publication From Hell to Breakfast Distinguished Service Medal, G.VI.R. (M. 31976 H. Howard, C.E.R.A.); British War Medal 1914-20 (M. 31976 Act. E.R.A. 4, R.N.); 1939-45 Star; Africa Star; Italy Star; War Medal 1939-45; Royal Navy L.S. & G.C., G.V.R., 3rd issue, coinage bust (M. 31976 E.R.A. 1, H.M.S. Cairo), together with Boston War Heroes Day Presentation Gold Medal (Mayor Maurice J. Tobin), 10-carat, dated 10 July 1942, the reverse engraved, ‘Harry Howard’, and Mayor of Salt Lake City Presentation Key, dated 23 June 1942, this engraved ‘Chief Artificer Harry Howard’, minor official correction to number on the second, the earlier awards a little polished, but otherwise very fine and better The Second World War campaign group of three awarded to his brother Sergeant J. A. Howard, Royal Army Ordnance Corps, who was taken P.O.W. at Dunkirk 1939-45 Star; War Medal 1939-45; Efficiency Medal, G.VI.R., Territorial (7599542 Sjt., R.A.O.C.), these extremely fine (12) £20,000-25,000() Only 24 Distinguished Service Medals were awarded for the St. Nazaire raid, the vast majority to men of Coastal Forces, Howard’s award being one of three to the Campbeltown. D.S.M. London Gazette 21 May 1942: ‘For great gallantry, daring and skill in the attack on the German naval base at St. Nazaire.’ The overall movements and events aboard H.M.S. Campbeltown have largely been related in the footnote to the D.S.C. awarded to Warrant Engineer W. H. Locke (see Lot 1197), but luckily for posterity’s sake Harry Howard, a native of Sheffield, later published his own account of the raid in Carl Ollson’s wartime anthology From Hell to Breakfast, from which the following extracts have been taken: ‘At about 1.20 the Engineer Officer, who had been popping up and down from the deck, came to see me in the engine-room and said, ‘Only about ten minutes more. ‘I went into the stokehold for a last look round where men were watching the clock and handling the fuel controls. It was silent here except for the droning of the feed pumps and the roar of the oil burners. I made sure every man knew the handhold he was to cling to when the ‘Stand by to Ram ‘order came through .. By now the ship was shaking, and above the whine of the engines I could hear the sound of gun-fire. In the same instant the telegraph rang full steam ahead, and we pushed in every ounce of steam pressure we had. The old Campbeltown began to tremble till all the footplates were quivering and rattling. ‘Now for it, ‘I thought. My mouth felt a bit dry. Another minute or so, and then the loud speaker blared from the bridge - ‘Stand by to Ram! ‘Each man threw himself at his selected handhold, some at steel ladder rungs, others clasping stanchions. In a flickering glimpse I saw the Engineer Officer wedging his body against one of the side ribs in the engine-room, and then I sprang at the big wheel I had picked. But she struck even as I was leaping, and I was flung a full six yards down the engine-room, hitting a Chief Engineer full in the stomach and nearly knocking him out. All the lights went out, leaving only the blue glimmer of emergency lamps. There was an instant stillness, except for the hell that was now breaking loose on deck. The loud speaker called again: ‘Abandon ship! ‘That was not the order we expected. We had been told that if we jammed the gate properly, the order would be: ‘Finished with main engines. ‘With a sick feeling of disappointment I thought at first we had bounced off the gates (Nobody could know, when we planned this party, whether in fact that might not happen. The specially strengthened bows of the Campbeltown might have given way under the impact). So stopping some of the men who were leaving the stokehold, in case there might have been a slip-up in the order and we might after all still want steam, I rushed up on deck to the bridge to find the Captain. He told me: ‘Get your men up and away to hell out of it. ‘And as I looked forward I saw that I needn’t have asked about that order. The Campbeltown was jammed slap into the lock-gate, nearly at the point where it joined the dock wall. Her bows were buried inside the gate, and she was right on the place aimed for on the sketch plan at the conference two days before. As a piece of masterly navigation on the part of the Captain that was the most wonderful thing I have ever seen in all my years at sea. I had no time to look at more or notice what else was going on around me. And there was plenty. The night had gone crazy with flashes and bangs and whistles from flying metal. I just legged it back to the engine-room and said, ‘It’s all right to come up, and you can get ashore all right from the fo’c’sle head. Beat it, everybody. ‘Then I went to do the final job to which I had been assigned. That was to unbolt the condenser inlet covers and to open the inlets, so that even if the explosive charges failed to go off, the Campbeltown would scuttle and block the channel into the dock and perhaps tear away part of the lock gate as well, as she sank. I had picked a young E.R.A. to do this job with me, and we worked by torchlight in the empty engine-room, because all the lights had now gone out. We worked quickly, but the job did not in fact take long, because I had previously loosened and removed many of the bolts. As I passed through the engine-room to go on deck for the last time I saw a young electrician busy with screwdriver and torch making some adjustments to the switchboard controlling the explosive fuses. He was whistling softly as though he was merely intent on a pleasantly interesting job. I never saw him again .. ‘Back on Campbeltown’s deck, Howard was compelled to get down and crawl amidst bullets and splinters which were rattling against the armour-plate along the rails: ‘It was bright moonlight and there was a vast pandemonium going on. Mixed with the din of their gun-fire I could hear the Campbeltown’s steam escape blowing off .. There were some wounded men being carried along towards the escape ladders and some dead .. Machine-guns were firing tracers towards us from the top of the lock pumping-house. Suddenly the firing stopped as the Commandos got there and wiped out the German crews with grenades .. The fo’c’sle was on fire, but we managed to get ashore by means of one of the bamboo scaling ladders used by the Commandos. I landed on the plank-covered top of the long deep channel slit into the dock wall which was designed to receive the lock gate. I slipped just as I was stepping off on to the level ground, and some ratings caught me. I could see the glare of the searchlights and gun-flashes that they were holding up a badly wounded Commando officer in kilts, and were getting him to rescue boats .. It is a sight I shall always remember; to see the dark forms of the dead and wounded men being carried aloft on the shoulders of their comrades, silhouetted against the glare of burning buildings and explosions, towards the rescue boats .. I had covered about 200 yards when we were challenged near the corner of some buildings. I flicked the answering colour on my signal torch and gave the password. They were two Commandos, placed there as guides to the boat. They had white armbands on, and stood there as calmly as though they were road cops seeing children safely over a school crossing. They waved us on in the right direction. At the boat a young Lieutenant on the bridge was calling out, ‘Come along, come along! ‘and then, ‘Any more for the Skylark? Any more for the Skylark? ‘I checked all my men on boar

A particularly fine Second World War Coastal Forces D.S.M. group of five awarded to Temporary Lieutenant (E.) R. J. A. Bunce, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, who was decorated for his gallant deeds as a Chief Motor Mechanic in the 50th M.G.B. Flotilla Distinguished Service Medal, G.VI.R. (A.C.M.M. R. J. A. Bunce, P/MX. 98931); 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star, clasp, France and Germany; War Medal 1939-45; Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve L.S. & G.C., G.VI.R., 2nd issue (Ty. Sub. Lieut. (E.) R. Bunce, R.N.V.R.), mounted as worn, together with his wartime identity disc, good very fine or better (6) £1400-1600 D.S.M. London Gazette 9 May 1944. The original recommendation states: ‘Acting Chief Motor Mechanic Bunce has consistently shown skill and devotion to duty of a high order. On the night of 3 August 1943, when in M.G.B. 604 under my command, the boat was rammed in the engine room. Bunce worked up to his waist in oil and water, with the engine room full of wreckage and steam, and kept one partly submerged engine running for six hours and 33 minutes. He repeatedly dived below the engine, at great risk of being caught in the turning shafts, and was eventually successful in cutting the water inlet suction pipe so that the engine drew water out of the bilges. During the action on the night of 24-25 October 1943, the lights failed in the plotting house, on the bridge, and down the whole port side of the ship [M.G.B. 609], due to a sudden short. He effected emergency repairs under difficulty in 30 seconds, thus materially assisting in the continuation of the action.’ Robert Joseph Arthur Bunce was born in Tooting, London in July 1915 and joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve as an Ordinary Seaman in March 1936. A Signalman serving aboard the cruiser H.M.S. Ceres on the outbreak of hostilities, he came ashore in October 1940 to take up successive appointments in the naval bases Lanka in Ceylon and Sheba in Aden, following which he returned to the U.K. in June 1941. Thereafter, as verified by his service record, he was ‘discharged to R.N. engagement’, and by May 1942 was serving as an Acting Chief Motor Mechanic at the Portland Coastal Forces’ base Attack - here then the commencement of his long association with M.G.Bs. Moving to the Lowestoft base Mantis in June 1942, where he was recommended for a decoration for services in M.G.B. 21 that September, Bunce remained similarly employed until removing to the 50th M.G.B. Flotilla, operating out of Midge at Great Yarmouth, in May 1943. And it was in the course of this latter appointment, for gallant service in M.G.Bs 604 - when rammed and flooded - and 609, that he won his D.S.M. An indication of the importance of the actions fought by M.G.B. 609 and her consorts on the night of 24-25 October 1943 is to be found in the London Gazette of 15 October 1948, for therein was published a full account of the night’s proceedings, via Admiral of the Fleet Jack Tovey’s original despatch of 18 November 1943 - one of just four epic Coastal Forces’ actions chosen for post-war publication to represent the many daring feats and sacrifices made by that gallant body of men in the ‘Battle of the Narrow Seas ‘, and beyond. In it, Tovey describes a series of ferocious firefights with around 30 E-boats, at least two of which failed to return to base. As part of the 50th Flotilla, operating out of Midge at Great Yarmouth, M.G.Bs 609 and 610 formed ‘Unit R ‘that night, the former commanded by Lieutenant P. N. ‘Pat ‘Edge, R.N.V.R., with Bunce aboard, and the latter by Lieutenant W. ‘Bob ‘Harrop, R.N.V.R. - both officers shortly to be D.S.Cs. One and all were in for a busy night, but by dawn the two ‘Dogboats ‘had contributed towards a significant turning point in Coastal Forces’ fortunes, the whole by means of highly skilled radar work and disciplined gunnery - and cold blooded courage of a high order. In summary of 609’s and 610’s engagements that night, Tovey stated in his famous ‘Coastal Forces Despatch ‘: ‘Unit R - M.G.Bs 609 and 610 - moved up to their northerly position at about 0100, and obtained hydrophone contact and then radar contact even before they were alerted by shore radar. From 0100 to 0141 Unit R stalked the enemy, keeping between him and the convoy. As soon as the enemy showed signs of closing the convoy, Unit R attacked, twice forcing him to withdraw to the eastward, the second time for good. The second boat in the line, on which 609 and 610 concentrated their fire, was undoubtedly hit hard and forced to leave the line. This group of E-Boats was the only one to operate north of 57F buoy, east of Sheringham .. the Senior Officer of this unit, Lieutenant P. Edge, showed a quick and sound appreciation of the C.-in-C’s object in fleeting the unit, i.e., the defence of the northbound convoy, and throughout handled his unit with tactical ability of a high order. Skilful use of radar gave him an exact picture of the enemy’s movements and enabled him to go into action at a moment of his own choosing. The moment he chose was entirely correct and there is no doubt that this well fought action saved the convoy from being located and attacked.’ Bunce remained actively employed in 609 until May 1944, when he removed to M.T.B. 734, in which boat he served off Normandy prior to coming ashore in mid-July. Having then been commissioned as a Temporary Sub. Lieutenant (E.), he would appear to have ended his war with an appointment in the frigate Grindall. Sold with a quantity of original documentation, including Admiralty letter of notification for the award of the recipient’s D.S.M., dated 11 May 1944, and related Buckingham Palace forwarding letter in the name of ‘Sub. Lieutenant (E.) R. J. A. Bunce, D.S.M., R.N.V.R.’; official letters regarding the award of his L.S. & G.C. Medal, dated in March and May 1949; his R.N. and R.N.V.R. Certificates of Service and Signal History Sheet; a Sea Cadet Corps letter confirming his advancement to the rank of Temporary Lieutenant; and an interesting selection of wartime photographs (approximately 10), including M.G.B. crew line-up and scenes of the U-532 arriving at Liverpool on 17 May 1945.

A rare and impressive East Africa 1941 operations immediate D.F.M. group of six awarded to Sergeant J. G. P. Burl, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve: in the unenvious position of being a Lysander air gunner under attack - and having had two or three bullets pass through one of his hands - he managed to force down an Italian CA. 133 and damage a CR. 42, following which his own aircraft crash-landed after serious damage inflicted by Italian fighter ace Maresciallo Soffritti - still under attack, he then proceeded to drag his unconscious pilot clear of the Lysander’s wreckage before leading him through difficult terrain to the safety of a Sudan Defence Force camp Distinguished Flying Medal, G.VI.R. (776358 Sgt. J. G. P. Gurl, R.A.F.), note surname spelling; 1939-45 Star; Africa Star; Italy Star; Defence and War Medals, generally good very fine (6) £2500-3000 D.F.M. London Gazette 1 April 1941. The original recommendation states: ‘On 2 February 1941, while on reconnaissance patrol off the Scipitale-Tole road in Lysander N. 1206, three CA. 133 aircraft were encountered. After a careful search which failed to locate escorting fighters, Flying Officer Johnson attacked the formation. As a result of this attack, one CA. 133 was forced to land but crashed in doing so. Flying Officer Johnson was then attacked himself by three CR. 42s which had evidently been ‘sitting in the sun ‘. In the first attack, Sergeant J. G. P. Burl, the Air Gunner, was wounded in the hand by two or three bullets which passed through it. However, in spite of this, he succeeded in firing off three pans of ammunition and evidently caused some damage to one of the enemy fighters as it was seen to break off its attack with smoke emanating from the engine area. Enemy fire caused the destruction of the flying controls of the Lysander and the pilot was forced to attempt a landing by increasing the engine revolutions and momentarily he succeeded in clearing a ridge ahead of him, although the elevators were ineffective, and throttled back to effect a landing on the other side. By a combination of wing dropping, which could not be corrected as the ailerons were not under control and an obstruction in the landing path, the aircraft crashed on landing and Flying Officer Johnson was rendered unconscious. He was extricated from the wreckage by Sergeant Burl. While this was being done, one CR. 42 continued the attack. The engagement occurred in the hills to the end of Tole and, when Flying Officer Johnson recovered, the crew set off on foot in a northerly direction in order to avoid possible Italian forces withdrawing along the road. The country was difficult and after a few miles, Sergeant Burl found it necessary to give Flying Officer Johnson considerable assistance in addition to carrying a three gallon water tank which he had removed from the aircraft. Later, they met some natives who put them on donkeys and led them into a Sudan Defence Force H.Q. camp where they received first aid attention and they were subsequently sent back by ambulance.’ John Graham Ponsonby Burl was serving in No. 237 Squadron at the time of the above deeds, the subsequent award of his immediate D.F.M. being erroneously announced in the London Gazette under the surname ‘Gurl’. His pilot, Flying Officer Miles Johnson, was awarded the D.F.C. No. 237 Squadron was formed from No. 1 Squadron, Southern Rhodesia Air Force, in April 1940 and went operational against the Italians in East Africa in June 1940, flying out of Nairobi, Kenya. Thus ensued a busy round of operations against enemy positions, troops and transport, in addition to Army co-operation work alongside such units as the King’s African Rifles, an agenda that gathered pace with the Squadron’s move to the Sudan that September - Burl’s brother, Alan, was also serving as an Air Gunner in 237 and became the Squadron’s first fatality when killed in a combat against CR. 42s on 27 November. In early 1941, 237 lent valuable support to the ground offensive against the Italians at Kassala and Keren, and it was in a related mission on 2 February that Burl won his immediate D.F.M. - in addition to the remarkable engagement recounted above, it is worth noting from the Squadron’s history that a Daily Express correspondent was on hand to witness Burl and Johnson stagger back into their base: ‘He reported that Burl, though in great pain and suffering from loss of blood, had carried the pilot a considerable distance on his shoulders. It had taken the men two days to reach British lines.’ In March 1941, the Squadron was re-equipped with Gladiators and remained actively engaged until that May, so it is probable that Burl witnessed further action in the intervening period - certainly 12 accompanying original photographs include images of Gladiators, in addition to wrecked Italian aircraft.

Clark (Daniel Kinnear) The Steam Engine, A Treatise on Steam Engines and Boilers, 1889, four half volumes, folding plates, cloth; Kennedy (John) The History of Steam Navigation, 1903, illustrated, cloth; MacArthur (Iain C.) The Caledonian Steam Packet Co. Limited, 1971, dust wrapper; with fifteen others (21)

A pair of Empire style gilt metal candelabra each with a central caryatid draped in a chemise supporting three engine turned sconces, on scrolling anthemion branches united by a similarly decorated tapering column, on verde antico marble and gilt metal framed stepped plinth bases with paw feet (2) 18cm wide, 45cm high, 11cm deep

A French late 19th century white marble and gilt metal mounted mantel timepiece the drum shaped engine turned dial with enamelled Roman and Arabic chapters between twin columns with pineapple finials surmounted by an urn, the stepped plinth base on bun feet, movement stamped 'Gossellin, A Paris' 16cm wide, 28cm high, 9cm deep

AN 8MM FRENCH FIVE-SHOT CENTRE-FIRE GAULOIS PATENT PALM PISTOL BY ARMES ET CYLCES MANUFACTURE FRANCAISE, ST ETIENNE, NO. T16244, CIRCA 1880 with short sighted barrel retaining traces of inscription on the flat, engraved engine turned blued action decorated with a trellis pattern filled with flowerheads, fitted with safety on the left, sprung squeezer action, and bakelite palm: in its felt case with German silver clasp (light moth damage) 13cm; 5 1/8in See L. Winant 1956, p.83 fig. 74.

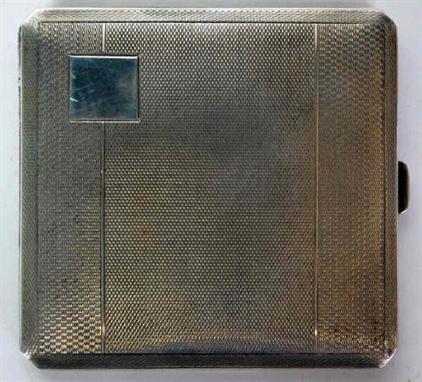

[Fox hunting interest] A Victorian silver rectangular snuff box by Francis Clark, Birmingham 1843, the cover engraved with hounds chasing a fox, within flower and foliate chased shaped borders with chamfered edges and a conforming chased thumbpiece, the sides engine turned, the engine turned base engraved with a crest, the interior gilt, 9.8cm (4in) wide, 206g (6.5 oz)

An Art Deco mother of pearl dress set, circa 1930, the double sided cufflinks centrally set with a half pearl above a mother of pearl panel and engine turned corners, with 4 buttons and 2 studs en suite, all stamped '9ct', in a fitted gilt tooled red leather Cartier case with a later silk lining for Tessiers 26 New Bond Street

Le Roy & Son, London, an 18 carat gold open faced pocket watch, London 1886, ref 48028, the two piece case with engine turned Arabic dial, the English lever fusee movement with a bimetallic split balance and over sprung balance spring, with a fancy fetter and three Albert chain to a 'T' bar clasp with a foiled seal engraved citrine seal attached, 39g gross

A George IV silver snuff box, raised floral borders and engine turned, to the hinged cover an engraved panel of a coursing scene, gilded interior with inscription 'Presented by The Strathern Coursing Club to Mr James Robertson, Farmer, in Henhill; As a mark of the high sense the Members entertain of the uniform kindness and attention they have on all occasions received from him, since the establishment of the Club, 14th February 1824', Birmingham 1823, maker Thomas Shaw, 9cm (3 1/2in) wide, 5.5 troy oz

Five Pieces of Turned Coromandel Treen: Two round flat snuffboxes with screw-on lids; one with engine turned geometric ornamentation. Two small cylindrical cases with screw-on lids; one with flat lid, the other with stepped lid centred by an ivory finial knop. A needle case with finialed screw-on lid and tapering sides on a pedestal foot.

-

186062 Los(e)/Seite

![[Fox hunting interest] A Victorian silver rectangular snuff box by Francis Clark, Birmingham 1843, the cover engraved with h](http://lot-images.atgmedia.com/SR/10011/2744562/671-166-10011_468x382.jpg)