186049 Preisdatenbank Los(e) gefunden, die Ihrer Suche entsprechen

186049 Lose gefunden, die zu Ihrer Suche passen. Abonnieren Sie die Preisdatenbank, um sofortigen Zugriff auf alle Dienstleistungen der Preisdatenbank zu haben.

Preisdatenbank abonnieren- Liste

- Galerie

-

186049 Los(e)/Seite

Early 20th century German three train architectural bracket clock, the case with architectural arched foliate pediment above rectangular aperture flanked by reeded Corinthian columns, overall decorated with scroll work and paterae. Steel, wood and engine turned Roman face with strike silent and regulatory dials, three train German brass movement, strikes on four gongs. Included pendulum. Overall 48.5cm high approx. (B.P. 21% + VAT) Rather grubby and dusty.

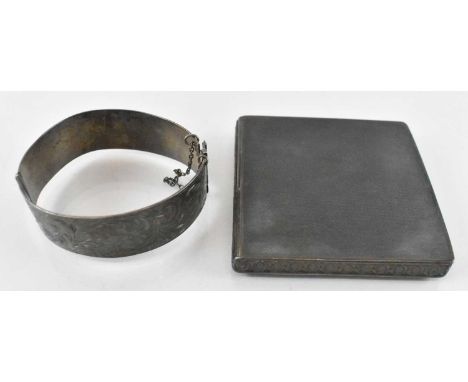

George V silver cigar box, of rectangular form, possibly Mappin & Webb, the hinged lid with engine turned designs above a three section interior, raised and standing on four shaped feet. London 1935. 18x10x6cm approx. (B.P. 21% + VAT) Good clear hallmarks. Minor dinks but overall good. Hinge working well.

1981 Mercedes 280SL Drop Head Sports Car, reg No. DHL 706. R107 Model. 2746ccs, six cylinder engine with four speed automatic transmission. Fabric retractable hood , factory hard top with stand. Long term local ownership (1998), now requiring some restoration and repair to obtain MOT certificate. Most recently MOT'd 2021-22. The car has stood since then and not been run. It has had an overhauled fuel system. V5c(w) document with transferable registration number (subject to MOT). Includes much history, bills, old MOTs, Mercedes Benz maintenance booklet etc. Historic Tax. (B.P. 15% + VAT) No guarantee or warranty of any kind implied or given. Sold as seen. Sold as seen with no warranty or guarantee of any kind. Vehicle requires restoration and repair.

A Baume gentleman's 18ct gold cased pocket watch, open face, key wind, circular enamel dial bearing Roman numerals, subsidiary seconds dial, movement number 3622, base metal cuvette, the case with engine turned decoration, vacant shield and garter reserve, 65.9g all in, together with keys, chains and a fob seal.

The Second War D.S.M. and Bar group of six awarded to Able Seaman S. D. Bennett, Royal Navy, who, having been originally decorated for his part in the famous boarding of the Altmark off Norway in February 1940, went on to win a Bar to his D.S.M. for services in H.M. Submarine Saracen in the Mediterranean: taken P.O.W. following her loss off Bastia in July 1943, he made at least two bids for freedom, one of them leading to him enjoying a period of several months at large, when he worked with the Italian partisans Distinguished Service Medal, G.VI.R., with Second Award Bar (JX. 136296 S. D. Bennett, A.B, H.M.S. Aurora.); 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; Africa Star; Italy Star; War Medal 1939-45, mounted as worn, extremely fine (6) £5,000-£7,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Sotheby’s, May 1989; Ron Penhall Collection, Dix Noonan Webb, September 2006. Eight D.S.Ms were awarded for the ‘Altmark Incident’, which with the addition of a Bar for services in submarines probably makes Bennett’s award unique; approximately 150 Bars to the D.S.M. were issued in the 1939-45 War. D.S.M. London Gazette 12 April 1940: ‘For gallantry and devotion to duty in the boarding of the Altmark.’ D.S.M. Second Award Bar London Gazette 20 July 1943. The original recommendation states: ‘During her one patrol at home, and eight in the Mediterranean, Saracen has sunk by torpedo two enemy supply ships and one transport, totalling 20,000 tons, two U-Boats and one destroyer; and by gunfire two large tugs and one anti-submarine schooner, and bombarded one shipyard; and damaged one large tanker by torpedo and carried out one successful special operation. Except in the case of the U-Boat, the attacks have been carried out against escorted ships and the Saracen has been depth-charged in consequence. Able Seaman Bennett is recommended for outstanding skill and devotion to duty as gunlayer during the above successful patrols in Saracen.’ Stanley Douglas Bennett was born in November 1915 and entered the Royal Navy in October 1931. Appointed an Able Seaman in 1934, he commenced his wartime career aboard the cruiser H.M.S. Aurora and, in common with a few other crew members, was transferred to the destroyer Cossack off Norway in early 1940. The Altmark Incident On the night of 16 February 1940, in an episode that would be widely reported in the home press, Captain Philip Vian, R.N., C.O. of the Cossack, commanded a brilliant enterprise in neutral waters in Josing Fjord, Norway, when 300 British merchant seamen were rescued from appalling conditions in the holds of the German auxiliary ship Altmark, all of them victims of earlier sinkings in the South Atlantic by the Graf Spee prior to her demise in the River Plate; their rescue was effected by a boarding party from Cossack, armed with revolvers, rifles and bayonets, one of whom was Able Seaman Stanley Douglas Bennett. As a result of the unfortunate delays caused by the implications of the Altmark being in neutral waters, and the presence of two Norwegian torpedo-boats ordered to prevent British intervention, Vian had patiently awaited Admiralty orders before embarking on his desperate mission, but when they arrived, with all the hallmarks of the First Sea Lord, Winston Churchill’s hand upon it, he moved swiftly. Vian’s account takes up the story: ‘Having placed Cossack in a position from which our pom-poms could play upon Norwegian decks, whilst their torpedo tubes were no instant menace to us, I said we could parley no longer, and must board and search the Altmark forthwith, whether we fought them or not. Kjell’s captain decided that honour was served by submitting to superior force, and withdrew. On rounding the bend in the fjord, Altmark at last came into view. She lay bows inshore, encased in ice, her great bulk standing black against the snow-clad mountains. Thoughts of the six-inch guns with which the Altmark was said to be armed were naturally in our minds. Though our own guns were manned we were obviously an easy target, and the enemy’s first shots might well immobilise us at once. There was nothing for it, however, but to go ahead and get to grips as quickly as possible. The Altmark’s Captain was determined to resist being boarded. On sighting Cossack, he trained his searchlight on our bridge to blind the command, and came astern at full power through the channel which his entry into the ice had made. His idea was to ram us. Unless something was done very quickly the great mass of the tanker’s counter was going to crash heavily into Cossack’s port bow. There followed a period of manoeuvring in which disaster, as serious collision must have entailed, was avoided by the skill of my imperturbable navigator, McLean, and by the speed with which the main engine manoeuvring valves were operated by their artificers. Lieutenant Bradwell Turner, the leader of the boarding party, anticipated Cossack’s arrival alongside Altmark with a leap which became famous. Petty Officer Atkins, who followed him, fell short, and hung by his hands until Turner heaved him on deck. The two quickly made fast a hemp hawser from Cossack’s fo’c’s’le, and the rest of the party scrambled across. When Turner arrived on Altmark’s bridge he found the engine telegraphs set to full speed in an endeavour to force Cossack ashore. On Turner’s appearance, the captain and others surrendered, except the third officer, who interfered with the telegraphs, which Turner had set to stop. Turner forbore to shoot him. It was now clear that as a result of her manoeuvres Altmark would ground by the stern, which she did, but not before Cossack, the boarding party all being transferred, had cast off, to avoid the same fate. It was expected, with the surrender of the German captain, that the release of our prisoners would be a drawing-room affair. That this was not so was due to the action of a member of the armed guard which Graf Spee had put aboard. He gratuitously shot Gunner Smith, of the boarding party, in an alleyway. This invoked retaliation, upon which the armed guard decamped; they fled across the ice, and began to snipe the boarding party from an eminence on shore. Silhouetted against the snow they made easy targets, and their fire was quickly silenced by Turner and his men. In the end German casualties were few, six killed and six badly wounded. The boarding party had none, save unlucky Gunner Smith, and even he was not fatally wounded. Resistance overcome, Turner was able to turn to the business of the day. The prisoners were under locked hatches in the holds; when these had been broken open Turner hailed the men below with the words: “Any British down there?” He was greeted with a tremendous yell of “Yes! We’re all British!” “Come on up then,” said Turner, “The Navy’s here!” I received many letters from the public after this affair: a number wrote to say that, as I had failed to shoot, or hang, the captain of Altmark, I ought to be shot myself.’ In point of fact Vian and his men were hailed as heroes the land over, Winston Churchill setting the pace with mention of their exploits in an address to veterans of the Battle of the River Plate at the Guildhall just four days after the Altmark had been boarded: “To the glorious action of the Plate there has recently been added an epilogue - the rescue last week by the Cossack and her flotilla - under the noses of the enemy, and amid the tangles of o...

The superb Great War C.B.E., Gallipoli ‘Y’ Beach D.S.O. group of six awarded to Commander A. St. V. Keyes, Royal Navy: the brother of Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes, his other claims to fame included service as a pioneer submariner in the Edwardian era, command of the Royal Canadian Navy’s first ever submarine flotilla in 1914, and the successful beaching of the ‘Q’ ship Mavis after she had been torpedoed in June 1917 The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, C.B.E. (Military) Commander’s 1st type neck badge, silver-gilt and enamels; Distinguished Service Order, G.V.R., silver-gilt and enamels, with integral top riband bar; 1914-15 Star (Lt. Commr. A. St. V. Keyes, D.S.O. R.N.); British War and Victory Medals (Capt. A. St. V. Keyes. R.N.); Coronation 1911, good very fine and better (6) £9,000-£12,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Dix Noonan Webb, September 2004. C.B.E. London Gazette 11 June 1919. D.S.O. London Gazette 16 August 1915: ‘In recognition of services as mentioned in the foregoing despatch.’ The despatch referred to was that of Vice-Admiral Sir John de Robeck, describing the landings on the Gallipoli Peninsula on 25-26 April 1915, and included General Sir Ian Hamilton’s report, which stated that ‘Lieutenant-Commander Keyes showed great coolness, gallantry and ability. The success of the landing on ‘Y’ Beach was largely due to his good service. When circumstances compelled the force landed there to re-embark, this officer showed exceptional resource and leadership in successfully conducting that difficult operation.’ Adrian St. Vincent Keyes was born in Secunderabad, India in December 1882, the son of General Sir Charles Keyes, G.C.B., and was appointed a Midshipman in May 1898 on passing out of the R.N. College Britannia. Advanced to Sub. Lieutenant in December 1901, and to Lieutenant in the following year, he joined the Royal Navy’s fledgling submarine branch in May 1903, in which trade he served more or less continuously until 1909, latterly with his own command - although his service record does note that he incurred their Lordships displeasure at the end of 1905 for some damage caused to the engine of H.M. submarine B3. Having survived this undoubtedly hazardous stint of “underwater service”, young Keyes returned to more regular seagoing duties, and in 1910, the year in which he was advanced to Lieutenant-Commander, he was appointed captain of the destroyer H.M.S. Fawn. According to a contemporary, although blessed with a ‘quick and brilliant brain’, Keyes was fortunate to squeeze through his destroyer C.O’s course - worse for wear as the result of a bad hangover, he bought a copy of The Daily Mail on his way to his final examination, and quickly memorised ‘the time of moon-rise, sunrise, high-water at Tower Bridge, and any other meteorological data the paper propounded’, thereby impressing their Lordships with his remarkably up-to-date knowledge. Interestingly, it was about this time that his brother, Roger, then a Captain, R.N., became senior officer of the submarine branch, an appointment that would act as the springboard to his rapid advancement in the Great War. For his own part, after another seagoing command, the Basilisk, Adrian Keyes was placed on the Retired List in June 1912. The outbreak of hostilities in 1914 found him out in Canada, where he was quickly appointed to the command of the Royal Canadian Navy’s first submarine flotilla, at Shearwater Island, in the rank of Lieutenant-Commander, the force comprising a brace of Holland-type submarines that had just been purchased by the somewhat eccentric Sir Richard McBride, K.C.M.G., the conservative premier of British Columbia - they had originally been built for the Chilean Navy in 1913. Duly christened the CC1 and CC2, Keyes took command of the former, while the latter went to another retired R.N. Officer, Lieutenant Bertram Jones. They were interesting days, not least since all of the labels and instructions in the two submarines were in Spanish. But Keyes and Jones showed great ingenuity in the face of adversity, even making some wooden torpedoes for battle practice until some real ones could be delivered from Toronto. Their respective crews, meanwhile, were packed off to Victoria public baths to practice underwater escape methods. In fact such rapid progress was made with the flotilla’s training programme that Keyes was in a position to sanction its first patrol, a 24-hour run down the Strait of Juan de Fuca, by the end of September 1914. Realistically, however, he realised that his chances of seeing combat in the immediate future were slim, so in January 1915, he successfully applied for an appointment in the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. Before his departure, however, he was presented with a splendid gold pocket watch by the CC1’s crew. Happily, as luck would have it, he joined his brother Roger - by now Chief of Staff to Vice-Admiral Sir John de Robeck - in H.M.S. Queen Elizabeth, the Admiral’s flagship, as ‘additional for disembarkation duties’, Roger noting in his memoirs how delighted he was to hear of the appointment. Indeed he would also describe in his memoir the events that took place at ‘Y’ Beach on 25-26 April 1915, and the subsequent deeds of his brother, Adrian: ‘There was to be another subsidiary landing on the western flank of the Peninsula at ‘Y’ beach by the Scottish Borderers, the Plymouth Division of the Royal Marines - borrowed from the Naval Division - and a company of the South Wales Borderers ... This landing was to be conducted by my brother Adrian, who had trained the troops to a high state of efficiency in boat work and speedy silent landing ...’ Although the ‘landing proceeded exactly as planned’, subsequent Turkish assaults penetrated the British line, and, at length, the military commanders offshore ordered that the beach be evacuated. Roger Keyes continues: ‘The captain of the destroyer Wolverine was killed on the morning of the 28th; she was a sister ship to the Basilisk, which my brother Adrian had commanded just before he retired, so the Admiral gave him the vacancy. Adrian could not be found until the following day, as after his ‘Y’ Beach had been given up, he attached himself to the troops which were to assault Achi Baba, where he was to establish a naval observation station directly it was captured. He came aboard to report himself on the 29th. I think his feelings were mixed; he said he could hardly bear to tear himself away from the Army. We could get very little out of him, except his intense admiration for the 29th Division and his sorrow at seeing most of the officers of the Scottish Borderers, with whom he had made great friends, killed alongside him. We gathered from him that Brigadier-General Marshall, who was wounded on the 25th but remained in action, like the two Brigadiers of the Division, was always in the thick of every action. I think my brother’s condition was typical of that of the 29th Division - dead dog-tired. He had been fighting incessantly since the 25th, and had hardly slept since the night of the 23rd. His new ship was undergoing repairs, half of her bridge having been shot away, when her captain was killed, so I made him lie on my bed, where he lay like a log for several hours ...’ Adrian Keyes was duly decorated for his work with the Army, three senior military commanders remarking how glad they were to hear of his D.S.O. And he went on to perform ster...

The ‘Juba River 1893’ group of four awarded to Able Seaman Charles Clift, Royal Navy East & West Africa 1887-1900, 2 clasps, Witu August 1893, Juba River 1893 (C. Clift, A.B., H.M.S. Blanche.); 1914-15 Star (129434, C. Clift. A.B. R.N.); British War and Victory Medals (129434 C. Clift. A.B. R.N.) mounted court style for display, very fine and better (4) £3,000-£4,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Alan Hall Collection, June 2000. 42 clasps for ‘Juba River 1893’ issued to the Royal Navy, 24 in combination with the clasp ‘Witu August 1893’. Charles Clift was born on 8 December 1869, in the village of Freshford in Somerset. He joined the Royal Navy on 9 December 1884, aged 15 years, as a Boy 2nd Class aboard the Training Ship H.M.S. Impregnable. On 20 December 1884, less than a month after first joining Impregnable, he was transferred to H.M.S. Lion. Whilst serving, he was advanced to Boy 1st Class on 17 February 1886, and on paying off in October 1886 he was sent to the Receiving Ship Royal Adelaide. Clift was next afloat aboard the Audacious, Flagship China Station, Vice Admiral R. V. Hamilton, C.B., which he joined in November 1886. Over the course of the three years he served aboard this ship he was advanced to Ordinary Seaman on 8 December 1887, and thus began his adult service. On paying off he joined the Duke of Wellington in February 1890. He next served aboard the Active from June 1890; the Vivid from December 1890; and Blanche from December 1890. Whilst in the latter vessel he was advanced to Able Seaman on 1 May 1891. During the three and a half years he spent in the 3rd Class Cruiser Blanche, Commander G. R. Lindley R.N., much of which was in East African waters, Clift was twice landed for service on shore with the ship's Naval Brigade. On the first occasion he was a member of a Naval Brigade consisting of 10 officers, 220 seamen and 36 Royal Marines drawn from H.M. Ships Blanche, Sparrow and Swallow. The Naval Brigade landed at Lamu on 7 August 1893, to punish Furno Omari, Sultan of Witu, who was openly rebellious and defiant, and had committed a number of atrocities. The stronghold villages of Pumwani and Tongeri were attacked; the gates of Pumwani were blown up by a field gun and war rockets and both towns were taken after a short, sharp fight. The Naval Brigade lost one stoker killed, and had two officers and six seamen wounded. Following their successful action, the members of the Naval Brigade returned to their respective ships on 15 August 1893. Each member was later to receive the East and West Africa Medal with Clasp 'Witu August 1893 '. A week after returning on board Blanche, Clift again volunteered to land as part of a much smaller Naval Brigade under Lieutenant P. V. Lewes, R.N. On hearing the news that Mr W. G. Hamilton, Superintendent of Askaris, had been murdered at Turki Hill, and that Count Lovattelli and Mr Farrant of the Imperial British East Africa Company were under siege at the British Residency at Kismayu, Commander G. R. Lindley of H.M.S. Blanche took the decision to land a small Naval Brigade to rescue them. The all-volunteer party of 42 sailors and stokers were joined by an additional 50 loyal Keribotos when they landed at the mouth of the Juba. Following a tiring night march, the force arrived at Turki Hill on 24 August, which was taken after a brisk fight. The small defending force at the Residency was relieved; upon hearing that Captain Tritton and Mr McDougall were trapped aboard the British Imperial East Africa Company's steamer Kenia at nearby Gobwen on the Juba River, Lieutenant Lewes and his small force set out to rescue them. On finding the two Englishmen safe, Lieutenant Lewes decided to fortify the steamer by placing iron plates, cut-up canoes, sand bags and bales of goods around the sides. Two maxim guns were mounted, and the Hotchkiss gun in the bow was manned. On 25 August the steamer set off up river to punish the mutineers and to destroy the town of Kajwalla. After proceeding only a short distance, the engine donkey feed pump broke down and the boiler fires had to be drawn. The element of surprise had been lost and the Kenia came under heavy fire from the mutineers concealed on the banks of the Juba River. The repairs to the pump, which took four hours to complete, were carried out by the engine room ratings. The steamer then continued upriver to shell and destroy the village of Magarada. After further shelling and firing of rockets, 30 men were landed from the Kenia, and after one hour of fighting, the town of Kajwalla was taken, burned and destroyed. The Kenia then crossed to the other side of the river, landed every available man, and after a brisk fight the town of Majawen was captured and destroyed. The Naval Brigade then returned to the Kenia and soon after rejoined the Blanche. For his services, Lieutenant P. V. Lewes received the Distinguished Service Order. The members of the Naval Brigade received the East & West Africa Medal with clasp 'Juba River 1893'. Those who were present at the previous action at Witu earlier in the month received the clasp only. On returning to England, Clift subsequently served short spells aboard the following ships: Victory I from March 1894; Excellent from June 1894; and Enchantress from October 1894. He then joined the Inflexible in May 1895; Victory I in September 1896; Vulcan in October 1896; and Victory I once again in October 1897. In January 1898, Clift joined the battleship Majestic, Flag Ship of the Channel Squadron, Vice Admiral Sir Harry Rawson, K.C.B. In this vessel he served a four-year commission before being paid off to the Duke of Wellington in January 1902. After three months on shore he joined, in April 1902, the 1st Class Battleship Vengence, Channel Squadron. In April 1902 he joined the 1st Class Battleship Barfleur, Flagship Reserve Division, Portsmouth, Rear Admiral R. L. Groome C.V.O. His stay in Barfleur was short, for a month later in May he had already been transferred to the Vivid. In October 1905 he joined Impregnable, Flagship, Devonport, Admiral Sir Lewis A. Beaumont, K.C.B., K.C.M.G. Following two years spent aboard the latter ship, Able Seaman Clift was pensioned ashore having completed twenty years’ adult service. He was never awarded a Long Service and Good Conduct Medal, since on three separate occasions his character assessment fell below 'Very Good'. Shortly after his discharge, he joined the Royal Fleet Reserve at Devonport on 5 January 1908, and was mobilised on 2 August 1914 as an Able Seaman aboard the Majestic Class Battleship Caesar, serving with the 7th Battle Squadron in the English Channel. He remained aboard Caesar when the ship was transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet early in 1915. Following a short period aboard Vivid, which he joined in October 1917, Clift was transferred in February 1918 to Hecla II, Base Ship at Buncrana, and remained in this posting until he was demobilised in November 1919, having served his country for a total of 25 years. Sold with research including copied record of service.

The Great War C.G.M. group of seven awarded to Officer’s Steward R. J. Starling, for gallantry in action in the Q ship Stock Force on the occasion that Lieutenant Harold Auten won the Victoria Cross Conspicuous Gallantry Medal, G.V.R. (L.6027. R. J. Starling, Off. Std. 2Cl. English Channel. 30th July 1918) some official corrections to location; British War and Victory Medals (L.6027 R. J. Starling, O.S. 2. R.N.); Defence and War Medals 1939-45; Efficiency Medal, Territorial, G.VI.R., with two additional service bars (2217345 Cpl. R. J. Starling, R.E.); France, 3rd Republic, Medaille Militaire, mounted for display, good very fine (7) £10,000-£14,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Douglas-Morris Collection, Dix Noonan Webb, February 1997. C.G.M. London Gazette 14 September 1918. Medal Militaire London Gazette 17 March 1919. The ‘Q’ Ship H.M.S. Stock Force, also known as Charyce, under the command of Lieutenant Harold Auten, D.S.C., R.N., was torpedoed by the U.98 at 5pm on 30 July 1918. The torpedo struck the ship abreast of No. 1 hatch, entirely wrecking the fore part of the ship including the bridge, and wounding three ratings. Officer’s Steward Starling was pinned under the wreckage of the foremost gun, his head gashed, his jaw smashed and one arm sprained. A tremendous shower of planks, unexploded shells, hatches and other debris followed the explosion, wounding the first lieutenant, Lieutenant E. J. Gray, and the navigating officer Lieutenant L. E. Workman, and adding to the injuries of the foremost gun’s crew and a number of other ratings. The ship settled down forward, flooding the foremost magazine and between decks to the depth of about three feet. The ‘Panic party’, in the charge of Lieutenant Workman, immediately took to the boat and abandoned ship, and the wounded were removed to the lower deck, where the surgeon, working up to his waist in water, attended to their injuries. Meanwhile Auten, two gun’s crews and the engine-room staff, remained at their posts. The submarine came to the surface ahead of the ship half a mile distant, and remained there a quarter of an hour, apparently watching the ship for any doubtful movement. The ‘Panic party’ in the boat accordingly commenced to row back to the ship in an endeavour to decoy the submarine within the range of the hidden guns. The submarine followed, coming slowly down the side of Stock Force, about 300 yards away. Lieutenant Auten, however, withheld his fire until she was abeam, when both of his guns could bear. Fire was opened at 5.40pm; the first shot carried away one of the periscopes, and the second hit the conning tower, blowing it away and throwing the occupants high in the air. The next round struck the submarine on the waterline tearing her open following which the enemy subsided several feet into the water and her bows rose. She thus presented a large and immobile target into which Stock Force poured shell after shell until the submarine sank by the stern, leaving a quantity of debris on the water. During the whole of the action, Officer’s Steward Starling remained pinned down under the foremost gun after the explosion of the torpedo, and remained there cheerfully and without complaint, although the ship was slowly sinking under him. The Stock Force was a ship of 360 tons, and despite the severity of the shock sustained by the officers and men, she was kept afloat by the exertions of her ship’s crew until 9.25pm. She then sank with colours flying, and the officers and men were taken off by two torpedo boats and a trawler. The action is cited as one of the finest ever fought by a ‘Q’ Ship, and the well-deserved award of the Victoria Cross to the Lieutenant Harold Auten, D.S.C. was announced in the London Gazette on 14 September 1918. Officer’s Steward Starling survived the action and was awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal. Sold with copied extract from “Q” Boat Adventures, by Lieut.-Commander Harold Auten, V.C., R.N.R., covering this action.

The rare Great War ‘East Africa, Lindi operations C.G.M. group of eight awarded to Able Seaman Harry Johns, H.M.S. Thistle, who showed exemplary conduct in at once going below into the after flat, when the ship was hit by an enemy 4.1 inch shell, in order to assist in extinguishing the fire’ Conspicuous Gallantry Medal, G.V.R. (183788. H. Johns, A.B. H.M.S. Thistle. Lindi. 11. June 1917.); Africa General Service 1902-56, 1 clasp, Somaliland 1902-04 (H. Johns, Lg. Sea., H.M.S. Fox.); 1914-15 Star (183788. H. Johns. A.B., R.N.); British War and Victory Medals (183788. H. Johns. A.B. R.N.); Royal Navy L.S. & G.C., G.V.R., 1st issue (183788. Harry Johns. A.B. H.M.S. Thistle.); France, Third Republic, Medaille Militarie, blue enamel badly chipped on this; Croix de Guerre 1914 1917, with bronze palme, mounted as worn, contact marks, otherwise nearly very fine or better (8) £8,000-£10,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- C.G.M. London Gazette 19 December 1917: ‘For conspicuous gallantry during combined naval and military operations in the neighbourhood of Lindi, East Africa, on the 10th and 11th June, 1917. He showed exemplary conduct in at once going below into the after flat, when the ship was hit by an enemy 4.1 inch shell, in order to assist in extinguishing the fire, and by his coolness and judgement prevented the fire from spreading.’ Three C.G.M.s awarded for the Lindi operations in East Africa. Medaille Militaire London Gazette 28 August 1918. Croix de Guerre London Gazette 14 September 1918. Lindi, a port of German East Africa, was occupied by the British Forces in September, 1915, but ever since that time had been practically ‘bottled up’, the surrounding country being held by the Germans. Lindi does not lie on the coast, but on the northern shore of the estuary of the river Lukuledi, which is some seventy miles north of the Portuguese frontier. In view of operations that had been planned, it became very desirable in the summer of 1917, to clear a larger area round Lindi in order to secure a better water supply and to prepare the main exits from the town and harbour. With this object in view, the main Military force moved out on June 10th, 1917, and in three days had cleared the enemy from the estuary of the river. During these operations a surprise landing was carried out at a creek on the south side, where the Germans had a 4.1" gun which commanded the estuary and had proved very troublesome. This was a combined naval and military operation. Upon the Navy, represented by the Hyacinth, Severn, Thistle and Echo, devolved the duty of embarking some 2,800 troops and 700 porters and conveying them to their starting point. This had to be done under cover of night. To reach the selected landing place the heavily laden boats had to pass close to enemy positions. The passage by water started at 1800 on the 10th September, the night being dark and the tide fair. An officer, Lieut. Charlewood, D.S.C., of the Echo, led the advance in a motor boat and placed lights, invisible to the enemy, on prominent points as leading marks. Although the Germans appeared to know that there was some movement on foot they either reserved their fire or did not observe the tows of boats passing them. The Thistle and Severn, which were following the boats, were sniped at. The main column was successfully landed by 2230 and by 0600 the next morning had occupied the hills covering the landing. It was not until 0300 on the 11th that the Germans opened fire with their 4.8" gun. Their shooting was very wild and caused no damage. The Thistle, which had anchored to superintend and cover a landing, was obliged, by the low state of the tide, to remain stationary, but fortunately, she was hidden from the enemy by a thick mist which lasted till 0700. When the mist cleared away the Germans immediately opened fire on her and after about 20 rounds, scored one hit. This killed an E.R.A. and wounded a leading stoker, also causing extensive damage. The auxiliary exhaust, fire mains, dynamo pipes, and two bulkheads were pierced. The shell, after passing through the ship's side, struck the after magazine hatch, which it completely broke up. A fire started in the magazine flat, a small confined space with the magazine below it. After the burst of the shell, the flat was on fire, and filled with fumes, smoke and steam from the holed exhaust pipe. Mr. Mark Methuen, Gunner, followed by Leading Stoker George Pascall and Able Seaman Harry Johns went into the flat and succeeded in extinguishing the fire before any further harm resulted. They all suffered from the effect of the fumes, Mr. Methuen having to go on the sick list. When the fire was extinguished, Leading Stoker Pascall went to assist in the Engine Room. Here he found that the E.R.A. had been killed, but that Leading Stoker James Leach, who was wounded in two places, had continued to stand by the engines although the engine room was filled with steam and water was pouring through the burst fire mains. Leading Stoker Leach persisted in carrying on with his duty until ordered to go up for medical treatment. The expedition was successful, the enemy being driven from his positions and forced to retire inland. Mr. Methuen received the D.S.C., and Leading Stoker Pascal, A.B. Johns and Leading Stoker Leach were awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal for their conduct on this occasion. Harry Johns was born at Bristol on 1 December 1879, and joined the Royal Navy as a Boy 2nd Class on 10 May 1895. Hr progressively through the rates to become Petty Officer 2nd Class on 22 June 1905, but for some reason reverted to Able Seaman just 11 days later and remained as such until the expiration of his Continuous Service engagement on 3 December 1909. Joining the Royal Fleet Reserve on the following day, he was recalled for service on 2 August 1914, joining H.M.S. Challenger. He removed to H.M.S. Thistle on 17 April 1916, and to H.M.S. Defiance on 1 October 1918, from which ship he was Shore Demobilised on 16 May 1919. He received his L.S. & G.C. medal on 12 November 1917, shortly before he received the C.G.M. These and the two French awards are all confirmed on his record of service. Sold with copied record of service.

The extremely rare Empire Gallantry Medal pair awarded to Coxswain and R.N.L.I. Gold Medallist John Howells, Fishguard Lifeboat Empire Gallantry Medal, G.V.R., Civil Division (John Howells); Royal National Lifeboat Institution, G.V.R., gold (John Howells, Voted 17th December 1920.) good very fine or better (2) £7,000-£9,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- A total of 130 Empire Gallantry Medals were awarded in the period 1922-40, 62 Military, 64 Civil, and 4 Honorary awards. The Empire Gallantry Medal was superseded by the George Cross in September 1940 and surviving holders of the E.G.M. were required to exchange their award for the George Cross. Coxswain Howells had by this time died and his award is, therefore, in addition to the four Honorary awards which were not eligible for exchange, one of only ten E.G.M’s not exchanged for the George Cross. 11 Gold R.N.L.I. Medals and one Bar awarded during the reign of King George V, from a total of 118 gold awards from 1824-1996. E.G.M. London Gazette 30 June 1924: ‘Ex-Coxswain John Howells, Fishguard Motor Life-Boat. For rescuing, in circumstances of great peril, seven of the crew of the motor schooner Hermina of Rotterdam, which was wrecked in a N.W. gale on Needle Rock, off Fishguard, on the night of 3rd December 1920. To effect the rescue involved taking the life-boat into a position of great danger among rocks.’ Coxswain Howells was also awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution, together with three Silver and nine Bronze awards to the crew members of his life-boat: ‘3 December 1920. The three masted Dutch motor schooner Hermina, anchored outside Fishguard breakwater, Pembrokeshire, was dragging her anchors in a north-westerly gale. The self-righting motor lifeboat Charterhouse launched but, when she arrived, the schooner was grinding heavily on the rocks with tremendous seas making a clean breach over her. Veering down, in spite of great difficulties, seven men were taken off but the Master and two Mates refused to leave. Coxswain Howells prepared to return to Fishguard, but the lifeboat had sprung a leak and it was found impossible to restart her engine. Her sail was hoisted, but she lost her mizzen sail, which left her with only the mainsail set. Second Coxswain Davies and crew member Holmes succeeded in setting the jib sail and, although waterlogged, the lifeboat managed to reach her station at midnight, three hours later. Although flares were shortly after seen from the Hermina, the lifeboat was unable to return, and the schooner’s Master and First Mate were rescued by life saving apparatus; the Second Mate had drowned.’ In April, 1921, Coxswain Howells, his crew and lifeboat went on the train to London to receive their R.N.L.I. awards. Howells was 66 years old at the time of the rescue. As part of the R.N.L.I. Centenary celebrations in 1924, seven of the eight surviving Gold medallists were received at Buckingham Palace on 30 June by King George V, who presented each man with the Empire Gallantry Medal. The Charterhouse was the Fishguard Lifeboat from 1901 to 1931. It was instrumental in many gallant rescues but none more so than the famous rescue of the crew of the Dutch motor schooner Hermina at needle rock located between Fishguard lower town and Dinas Head. She was the first motorised lifeboat but also had the capacity for up to 12 persons to row. In 1920 Coxwain John Howells aged 66, received a call that flares had been sighted at needle rock and so on that cold dark December night he immediately put the Charterhouse to sea in perilous conditions and made way across the bay for needle rock. The Hermina under the command of Captain Vooitgedacht was on a return journey back to Rotterdam but diverted to Fishguard to escape the teeth of the strong NW gale. Once in the bay she dragged her anchors and ended up in a perilous position, being bashed by huge waves in between needle rock and the tall sheer north cliffs. Once the Charterhouse arrived, Howells gave order to anchor down wind and run a line between the two vessels, but this proved very perilous and after an hour of struggling against horrendous seas, the crew of the Charterhouse managed to get 7 men off the Hermina. The Chief Officer and Mate would not leave the ship despite the efforts of persuasion by the lifeboat crew. They were later rescued from the base of the cliffs by the coastguard. Their troubles at this point were far from over, the lifeboat’s engine would not restart and in a desperate situation the crew took to the oars in a frantic effort to get away from the cliffs but with little effect. The mizzen sail was then raised but caught the wind and ripped to shreds. In absolute frantic desperation a jib sail was lashed together which involved two men risking their lives climbing across the forefront of the lifeboat with waves crashing over them to set a temporary sail. In great relief they managed to pull away from the cliffs and sail 2 miles out to sea before getting sufficient angle to eventually be able to sail back into Goodwick harbour. The Dutch Government awarded Howells a gold pocket watch and silver pocket watches to all the lifeboat crew; the R.N.L.I. also awarded medals to all the crew of the Charterhouse and to John Howells the highest honour of a gold medal. The Charterhouse was loaded onto a train at Goodwick railway station and the entire crew made for London to meet the Duke of Windsor, President of the R.N.L.I. to receive their medals. The Charterhouse remained for one week on display outside the houses of parliament. The Charterhouse now resides at the West Wales Maritime Museum in Pembroke Dock where she is undergoing restoration to preserve this very important piece of Pembrokeshire maritime history. John Howells, as a young man served in the Royal Navy and was a shipmate of King George, then a naval cadet. On leaving the Navy, he entered the service of the Great Western Railway Company, and when Fishguard Harbour was opened for Irish traffic in 1907, he was put in charge of the coaling gang at the harbour under the Marine Department. He was a deacon of Bethesda Baptist Church, for many years its Honorary Treasurer, and Superintendent of the Sunday School. He was Coxswain of the Fishguard Lifeboat from 1910-21 and died at Fishguard on 14 March 1925, aged 72.

The rare Siberia 1919 ‘Kama River Flotilla’ M.S.M. group of four awarded to Private F. J. Williamson, Royal Marine Light Infantry, H.M.S. Kent 1914-15 Star (PLY. 15043. Pte. F. J. Williamson. R.M.L.I.); British War and Victory Medals (PLY. 15043. Pte. F. J. Williamson. R.M.L.I.); Royal Naval Meritorious Service Medal, G.V.R. (PLY/15043 Pte. F. J. Williamson. R.M.L.I. “Kent” Kama River May 1919.) mounted for wear, nearly extremely fine and rare (4) £600-£800 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- M.S.M. London Gazette 5 March 1920 'Honours for services in Siberia.' H.M.S. Kent relieved H.M.S. Suffolk at Vladivostock in January 1919. Williamson had been serving with the Armoured train manned by parties from the Suffolk, but with the arrival of Kent he transferred to that ship. It was decided to take the 6-inch gun and the four 12-pounders out of the armoured trains and place them in two ships of the Russian Naval Flotilla at Perm. Volunteers were called for from the Royal Marine Detachment of H.M.S. Kent and at the beginning of April, Captain T. H. Jameson and 34 Royal Marines, one mate, one surgeon-lieutenant, one warrant officer, one armourer and one sick berth attendant, Royal Navy, proceeded to Perm arriving on the 27th April on which day the ice broke and started to flow down the river. The Naval Mission remained first at Perm and then at Omsk whilst the Naval Force under command of Captain Jameson, R.M.L.I. joined the Flotilla. Practically all the ice had disappeared by the 1st May and they were introduced to Admiral Smirnoff, C.M.G., in command of the Russian Flotilla and were handed the two ships to be gunned and manned by the British. The British Force were allotted to the Third Division of the Flotilla, commanded by Captain Fierdoroff; the ships allotted to them were a fast oil driven tug and a barge. The 12-pounders were mounted in the tug which was christened the Kent and the 6-inch in the barge named Suffolk. Throughout May and June Kent and Suffolk were constantly and heavily engaged in fighting against Bolshevik forces, both on the river and providing artillery support for the land forces. All was to no avail, however, with the front troops falling back daily from the advancing Bolsheviks, and it was therefore decided to disarm the First and Third Divisions, the Second remaining at the front. On the 26th June Kent proceeded to the magazine, near which was the British Naval armoured train and commenced to dismantle, placing armour, guns, ammunition and stores in the train; on this day the Suffolk engaged the enemy in the Veltanka district, and again the next day at the village of Stralka she routed large numbers of the enemy at close range. She fired 256 rounds and having expended all her amunition was recalled to Perm, arriving at Motavaileka Works on the 28th. As no workmen could be obtained the crews of the two ships were obliged to dismantle the ships themselves and to load the material, all 225 tons of it, onto railway trucks for which they had no engine. Perm was expected to fall that night, confusion was everywhere, the station overflowing with refugees and every train was loaded to the fullest extent. As a last resort they searched the repair shop for an engine and took the only one available, which the Russians reluctantly gave them; it was only just capable of drawing the train and they eventually left Perm at 6 a.m. on 29th June, having sunk Kent and Suffolk the previous afternoon. The party of 37 of all ranks was crowded into two wooden trucks and travelling was very slow; their rations consisted of the biscuits and beef of their reserve rations. On arriving at Omsk they volunteered to form the British Naval Armoured Train but the Admiralty decided to withdraw the Force completely. Accordingly, they proceeded in two waggons to Vladivostock arriving there on 18th August, having taken 52 days to complete the journey from Perm. They were taken on board H.M.S. Carlisle and transferred at Shanghai to H.M.S. Colombo, reaching England on 10 November 1919. This gallant band of men received the following awards for their part in this remarkable episode: 1 D.S.O., 2 D.S.C.’s, 1 D.S.M. and 8 M.S.M.’s. Frank James Williamson was born on 24 December 1891 in the village of Freethorpe in Norfolk. He earned his living as a footman prior to joining the Plymouth Division of the Royal Marines on 10 August 1910. After recruit training at Deal he joined H.M.S. Hawke in February 1912, transferred to Merlin in March 1913 and returned to shore early in 1914. He next joined Benbow in October 1914 and served in this battleship until January 1917, taking part in the Battle of Jutland. He joined Suffolk in May 1917 and landed in Siberia for active service with Suffolk’s Armoured Train in August 1918 on the Ufa front. He transferred to Kent in January 1919 and landed as part of the Kama River Naval Expeditionary Force from which he returned to england via Carlisle and Colombo. He returned to the Plymouth Division in November 1919 and joined Valiant, his last seagoing ship, in May 1920 and remained with her until June 1922 when he was discharged having completed 12 years. He joined the Royal Marine Police where he served until discharged on 15 December 1945. Sold with full research including a copy of Captain Jameson’s ‘Report on the proceedings of the British Naval Force acting with the Kama River Flotilla.’

A Great War O.B.E. group of four awarded to Engineer Lieutenant-Commander F. J. Baker, Royal Navy, one of only six naval recipients of the Q.S.A. with clasp ‘Rhodesia’ The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, O.B.E. (Military) Officer’s 1st type, breast badge, reverse hallmarked London 1917; Queen’s South Africa 1899-1902, 1 clasp, Rhodesia (Art: Eng. F. G. Baker, R.N. H.M.S. Partridge) note second initial; British War Medal 1914-20 (Eng. Lt. Cr. F. J. Baker. R.N.); Royal Navy L.S. & G.C., V.R., narrow suspension (F. J. Baker, E.R.A. 2nd Cl., H.M.S. Anson) impressed naming, mounted court-style as worn, good very fine (4) £1,600-£2,000a --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Alan Hall Collection, June 2000. Only 6 Q.S.A. medals with clasp 'Rhodesia' awarded to the Royal Navy; all were awarded to Officers or Warrant Officers. O.B.E. (Military) London Gazette 16 September 1919: 'For valuable services at H.M. Dockyard, Sheerness'. Frederick John Baker was born on 25 November 1862, at Rochester, Kent. Prior to joining the Royal Navy at Pembroke on 7 January 1884 he was employed as a turner and fitter. Not surprisingly he elected to join the Engineering Branch of the Royal Navy and became an Acting Engine Room Artificer 4th Class Official No. 126,083. On leaving Pembroke having completed his basic training on 8 May 1884, he joined the receiving ship Victor Emannuel in Hong Kong. From this vessel he later joined the despatch vessel Vigilant on 24 June 1884. He was transferred to the gunboat Midge on 4 July 1884, and whilst in this ship he was advanced to Engine-Room Artificer 3rd Class on 7 January 1887. He returned to England in February 1889 and rejoined Pembroke. His next seagoing post was to the battleship Rodney which he joined on 14 May 1891. He was advanced to Engine-Room Artificer 2nd Class on 2 February 1891 and awarded his second Good Conduct Badge on 3 February 1892. He paid off from Rodney on 27 May 1892, and rejoined Pembroke. He remained on shore until 12 September 1893 when he joined the battleship Anson. During the three years he served in this ship he was advanced to Chief Engine-Room Artificer on 13 November 1894. He was awarded his Long Service & Good Conduct medal under the ten year rule on 19 September 1894. He returned to Pembroke II in November 1896 and passed his examination for Artificer Engineer (Warrant Officer rank) on 27 January 1898, and was promoted to the rank with seniority of 1 April 1898. As a Warrant Officer he was appointed in May 1899 to the gunboat Partridge, serving on the Cape of Good Hope and West Coast of Africa Station. The Queen's South Africa Medal Roll shows that 3 Lieutenants, 1 Surgeon and 2 Warrant Officers landed at Beira on the instruction of their Commanding Officer and as a result were later able to claim the Queen's South Africa Medal with clasp 'Rhodesia'. On leaving Partridge he was next appointed to the torpedo boat destroyer Hardy, which he joined on 29 September 1902. On promotion to Chief Artificer Engineer on 1 April 1903 he joined in April 1904 the cruiser Lancaster, serving on the Mediterranean Station. Whilst in this ship he was promoted to Engineer Lieutenant on April 1905. His next appointment on 17 June 1905, was to President where he was Assistant to the resident Naval Engineer Overseer Midland District. After three years in this post he was next appointed in October 1908 to the Zulu, torpedo boat destroyer building at Hawthom Leslie & Co., Newcastle upon Tyne. In May 1909 he joined Orion, coast defence and depot ship for torpedo boat destroyers, Malta. In this post he was responsible for training Malta reserve stokers and for supervision of boats etc. He subsequently served aboard the battleship Ocean, Third Fleet at the Nore which he joined in March 1911, followed by Wildfire October 1911 for service with the Commander of the Sheerness Dockyard. On 28 April 1916 he was promoted to Engineer Lieutenant-Commander and remained in this post for the duration of World War I. He was placed on the Retired List in January 1920, and died circa 1942-43. Sold with copied record of service and medal roll confirmation.

The unique and outstanding Great War Zeebrugge-Ostend D.S.C. and Bar group of six awarded to Captain C. F. B. Bowlby, Royal Navy, a founding father of Coastal Forces, he was awarded the D.S.C. and Bar for his gallant command of Coastal Motor Boat (C.M.B.) 26B in the Zeebrugge and second Ostend Raids in April-May 1918, the only officer so honoured. And he later added the C.B.E. to his accolades as a senior operative of M.I.6’s ‘Inter-Services Liaison Department’ in the last war, when recommended for his ‘outstanding leadership and skill in organising special operations in the campaigns fought in Africa, Sicily, Italy and the Balkans’; likewise the C.M.G. upon his retirement in 1956 for intelligence work during the ‘Cold War’ Distinguished Service Cross, George V, with Second Award Bar, the reverse privately engraved ‘Lieut. C. F. B. Bowlby, R.N., 23rd April 1918, Zeebrugge’, the reverse of the Bar privately engraved ‘May. 9-10. 1918.’; 1914-15 Star (S. Lt. C. F. B. Bowlby, R.N.); British War and Victory Medals, with M.I.D. oak leaves (Lieut. C. F. B. Bowlby. R.N.); Jubilee 1935; Coronation 1937, mounted court-style, very fine and better (6) £5,000-£7,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Sotheby’s, July 1998. C.M.G. London Gazette 2 January 1956. C.B.E. London Gazette 3 July 1945: ‘For excellent service in the organisation of special operations in the Near East.’ The original recommendation states: ‘Captain Bowlby has, since 1941, been in command of the intelligence organisation in the Mediterranean area which has been responsible for obtaining from the enemy, and enemy occupied territory, much important naval intelligence which has been used operationally to the discomfiture of the enemy. He is responsible for building this organisation up from zero and for maintaining a large network of intelligence agents which operated behind enemy lines in the Desert, Tunisia, Italy, Greece, and other parts of the Mediterranean area. The award of the C.B.E. to this officer is highly recommended.’ D.S.C. London Gazette 23 July 1918: ‘In recognition of distinguished services during the operations against Zeebrugge and Ostend on the night of 22-23 April 1918: Lieut. Cuthbert F. B. Bowlby, R.N. In command of a coastal motor boat. Showed great coolness under very heavy fire, stopping his boat abreast the seaplane sheds at a range of 60 to 70 yards, and continued firing, making numerous hits.’ D.S.C. Second Award Bar London Gazette 23 August 1918: ‘I have the honour to bring to the notice of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty the names of the following officers and men who performed distinguished service in the second blocking operation against Ostend on the night of 9-10 May 1918: Lieut. Cuthbert F. B. Bowlby, D.S.C., R.N. In command of a coastal motor boat, and escorted Vindictive close up to the entrance, then ran ahead, and finding one of the piers, fired a torpedo at it. The water being shallow and the range short, the explosion shook the boat so severely as to damage her engines and open up her seams. She commenced to sink, but by his presence of mind he got the leak stopped, engines going again, and brought his boat out of the fire zone, where, he was taken in tow by H.M.S. Broke.’ M.I.D. London Gazette 28 August 1918: ‘Ostend blocking operations 9-10 May 1918.’ Cuthbert Francis Bond Bowlby was born in Buckinghamshire on 23 August 1895, the son of the Rev. Henry Thomas Bowlby, and was educated at the Royal Naval Colleges Osborne and Dartmouth. A Midshipman serving in the battle cruiser H.M.S. New Zealand on the outbreak of war, he quickly saw action at the battles of Heligoland Bight in August 1914 and Dogger Bank in January 1915, in which latter month be became a Temporary Sub. Lieutenant. Zeebrugge and Ostend, April and May, 1918 In July 1916, Bowlby removed to a new ‘special service’ appointment on the Thames, namely to conduct early trials in prototype Coastal Motor Boats (C.M.Bs). Duly qualified in the type, he was advanced to Lieutenant and took command of C.M.B 26B in May 1917, and it was in this capacity that he was awarded his unique D.S.C. and Bar for the Zeebrugge raid on 22-23 April 1918 and the second Ostend raid on 9-10 May 1918. On the former occasion, he ‘showed great coolness under a very heavy fire’, when he stopped C.M.B. 26B 60-70 yards off the seaplane sheds, which he then engaged with accurate fire. On the latter occasion, as recounted by Sir Roger Keyes in his relevant despatch, Bowlby escorted Vindictive close to the entrance, and then ran ahead, for he had caught an all-important sighting of one of the piers: ‘Escorting Vindictive on her final approaches to the canal were two fifty-five-foot Coastal Motor Boats, 25B (Lieutenant R. H. McBean) and 26B (Lieutenant C. F. B. Bowlby). Their orders were to proceed ahead of Vindictive until within sight of the canal mouth, whereupon they would drop calcium light buoys and fire flare rockets to burst above and illuminate the canal entrance.

In thick fog this was much easier said than done, and Lieutenant Bowlby proceeded with a commendable caution which with anything other than damned bad luck should have been duly rewarded. For a moment, in fact, he thought it would be so rewarded, for there was a momentary gap in the fog and he glimpsed the eastern pier head at the very moment when his boat, his guns and his torpedo-tube pointed exactly at it. He pressed the button, discharged the torpedo and increased speed, with the result that he was directly above his torpedo when it hit either the bottom or a submerged object and exploded, blowing C.M.B. 26B several feet up into the air. She did not sink immediately, but her seams were badly parted, her communication system wrecked, and her signal and lighting arrangements reduced to chaos. Lieutenant Bowlby turned her away and took her slowly to seaward, with the port engine firing on six cylinders and the starboard engine bone dry, for the connections had burst and the engine casing was empty. C.M.B. 26B made nearly three miles before the port engine seized up and she was eventually towed home … ’ Subsequent career – Naval spook for the S.I.S. Bowlby was appointed a Flag Lieutenant in the battleship Glory at the war’s end and went on to enjoy a succession of seagoing appointments, including tours of duty in the battleships Valiant and Hood. So, too, steady promotion to Commander in June 1930. He also held his first major command, the aircraft carrier Hermes. Soon after the renewal of hostilities, however, he was borne on the books of President ‘for duties outside the Admiralty’, the first indication of his new-found career in the Secret Intelligence Service (S.I.S.). As revealed by the historian Nigel West in his related history of M.I. 6, Bowlby was to remain likewise employed until 1955. He had been personally selected by Stewart Menzies, then head of the organisation, to establish its credentials in the Middle East; as revealed by a captured enemy intelligence report after the war, his new appointment was duly registered by the Reich Security Agency. In his capacity as an Assistant Chief Staff Officer – or ‘G’ Officer in spook’s parlance – Bowlby was to spend three years in Egypt, running the Cairo post, where he oversaw the creation of the Inter Service Liaison Department (I.S.L.D.), prior to establishing similar posts at Algiers ...

The Second War ‘Fall of Singapore’ D.S.M. group of six awarded to Stoker P. A. H. Dunne, Royal Navy, for a motor launch versus Japanese destroyer action of “Li Wo” proportions: few escaped the resultant carnage inflicted by several point-blank hits on H.M.M.L. 311’s hull and upper deck and those that did had to endure over four years as a P.O.W. of the Japanese, the wounded Dunne amongst them Distinguished Service Medal, G.VI.R. (Sto. P. A. H. Dunne, P/KX 132616); 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; Pacific Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, mounted as worn, minor contact marks, good very fine or better (6) £4,000-£5,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- D.S.M. London Gazette 19 February 1946: ‘For great gallantry, although wounded, in keeping the engine room services of H.M.M.L. 311 in action after an attack by a Japanese destroyer on 15 February 1942.’ The original recommendation states: ‘During the engagement between H.M.M.L. 311 and a heavy Japanese destroyer on 15 February 1942, when the remainder of the Engine Room personnel had been killed, and heavy damage sustained in the Engine Room, the above rating continued to keep the Engine Room services in action, under the most trying conditions. Throughout the engagement, being himself wounded in the leg, Stoker Dunne worked in close proximity to blazing petrol tanks, and in additional danger from pans of live Lewis gun ammunition bursting into flames, some of which penetrated the Engine Room. He remained carrying out E.R. duties until the order to abandon ship was received.’ Percy Albert Holmes Dunne, a native of Whitley Bay, Northumberland, who was born in November 1921, was recommended for his immediate D.S.M. by Commander V. C. F. Clarke, D.S.C.*, R.N., in October 1945, when the latter, the senior surviving officer from H.M.M.L. 331, submitted his official report of the action to Their Lordships: ‘I have the honour to submit the following report of the passage of H.M.M.L. 311 from Singapore to Banka Straits and her sinking there by enemy action. This report is forwarded by me, as Senior Naval Officer on board, in the absence of her Commanding Officer, Lieutenant E. J. H. Christmas, R.A.N.V.R., whose subsequent fate is unknown. I embarked on H.M.M.L. 311 on the afternoon of 13 February 1942, as a passenger. Orders were later received from R.A.M.Y., through Commander Alexander, R.N., to embark about 55 Army personnel after dark, then proceed to Batavia via the Durian Straits ... At daylight on the 15th, we sighted what appeared to be a warship from 2 to 3 miles distant, almost dead ahead, in the swept channel, at a fine inclination, stern towards us and to all appearances almost stopped. We maintained our course, being under the impression that this was probably a Dutch destroyer. When about a mile away the destroyer altered course to port and was immediately recognised by its distinctive stem as a Japanese destroyer of a large type. At Lieutenant Christmas’ request, I took command of the ship and increased to 18 knots, maintaining my course, to close within effective range. The enemy opened fire and, with the first salvo, scored two hits, one of which penetrated the forecastle deck, laying out the gun’s crew, putting the gun out of action and killing the helmsman. Lieutenant Christmas took the wheel, and I increased speed to approximately 20 knots, and made a four-point alteration of course to starboard to open ‘A’ arcs for the Lewis guns, now within extreme range. This brought me on a course roughly parallel and opposite to the enemy enclosing the Sumatra shore, which, in the almost certain event of being sunk, should enable the crew and the troops to swim to the mainland. On my enquiring, after the alteration, why the 3-pounder was not firing, I was informed it was out of action. By constant zig-zagging further direct hits were avoided for a short time, during which the light guns continued to engage the enemy. The enemy, however, having circled round astern of me, was closing and soon shrapnel and direct hits began to take their toll both above and below decks. The petrol tanks were on fire, blazing amidships, and there was a fire on the messdecks. The engine room casing was blown up and two out of three E.R. personnel had been killed, whilst the third, a Stoker [Dunne], was wounded in the leg. The port engine was put out of action. The E.R. services as a whole, however, were maintained throughout the action. Finally, Lieutenant Christmas at the helm reported the steering broken down with the rudder jammed to starboard. We began circling at a range of about 1000 yards. Further offensive or defensive action being impossible, with all guns out of action and the ship ablaze amidships, I stopped engines and ordered ‘abandon ship’. Casualties were heavy. I estimate that barely 20 men, including wounded, took to the water. The Japanese destroyer lay off and, although the White Ensign remained flying, ceased fire but made no attempt to pick up survivors. I advised men to make for the mainland shore but a number are believed to have made for the middle of the Strait in the hope of being picked up. The action lasted about ten minutes. The captain of the Mata Hari (Lieutenant Carson), who witnessed the action, states that the Japanese ship fired 14 six-gun salvoes. There were four, or possibly five, direct hits, and, in addition to the damage from these, most regrettable carnage was caused on the closely stowed upper deck by bursts from several “shorts”. The ship sank not long after being abandoned, burning furiously.’ Other than Dunne, no other officer or rating appears to have been decorated for the action, Clark’s D.S.C. and Bar having stemmed from acts of gallantry in the Second Battle of Narvik and during earlier air attacks off Singapore; sadly the fate of Lieutenant E. J. H. Christmas, R.A.N.V.R., was never fully established, and he is assumed to have died on 15 February 1942. Sold with the recipient’s original Buckingham Palace returning P.O.W’s message, dated September 1945, together with a quantity of related research, including copied recommendation, Japanese POW card, and a copy of Commander Victor Clark’s memoirs, Triumph and Disaster, in which he describes the demise of H.M.M.L. 311 in detail.

The Great War D.S.O. group of five awarded to Captain J. E. A. Mocatta, Royal Navy, who was decorated for his magnificent bravery and skill in command of the destroyer Nicator at Jutland, where he once engaged the enemy at the suicidal range of 600 yards, under ‘a perfectly hair-raising bombardment’, all the while ‘leaning coolly against the front of the bridge, smoking his pipe, and giving orders to his helmsman’ Distinguished Service Order, G.V.R., silver-gilt and enamels, with integral top riband bar; 1914-15 Star (Lieut. J. E. A. Mocatta, R.N.); British War and Victory Medals, with M.I.D. oak leaves (Lt. Commr. J. E. A. Mocatta, R.N.); Russia, Empire, Order of St Stanislas, 3rd Class neck badge with swords, 40mm x 40mm., gold and enamel, manufacturer’s name (probably Edouard) on reverse, ‘56’ gold mark for St. Petersburg 1908-17 on eyelet, further stamp marks on sword hilts, mounted for display, good very fine and better (5) £6,000-£8,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: R. C. Witte Collection, Dix Noonan Webb, December 2007. D.S.O. London Gazette 15 September 1916: ‘He supported Commander Bingham of Nestor in his gallant action against destroyers, battle-cruisers and battleships, in the most courageous and effective manner.’ M.I.D. London Gazette 6 July 1916. Order of St Stanislas, 3rd Class London Gazette 5 June 1917. Jack Ernest Albert Mocatta was born in Paddington, London in April 1887 and entered the Royal Navy as a Naval Cadet in Britannia in May 1902, and was appointed Midshipman in the Empress of India on the Mediterranean Station in October 1903. Advanced to Lieutenant in October 1909, after surviving the loss of the Gala in a collision in the previous year, he was serving in the destroyer Brisk on the outbreak of hostilities in August 1914. As it transpired, he would remain actively employed in destroyers for the remainder of the War, his subsequent pre-Jutland appointments being the Angler (March to September 1915), the Sunflower as C.O. (September 1915 to January 1916), and the Sandfly as C.O. (February to May 1916), in which latter month he removed to the Nicator. And judging by assorted reports on his service record, he was the very epitomy of a destroyer captain - dashing, plucky, skilful and energetic, and blessed with a healthy disregard for minor detail and paperwork. At Jutland, Mocatta’s Nicator was in the 2nd Division of the 13th Destroyer Flotilla, and the port division of that force was commanded by the equally dashing Harry Bingham, the son of an Anglo-Irish nobleman, in Nestor; the team was completed by Nomad, under Lieutenant-Commander Paul Whitfield. Very shortly the home press would be buzzing with tales of their exploits, not least of the award of the V.C. to Barry Bingham, and, as the following account confirms, no-one lent better support to that gallant officer than Mocatta of the Nicator: ‘At 4.15 the port division, led by Commander the Hon. Barry Bingham in the Nestor, swerved out of line at full speed to attack. Other divisions followed, until, steaming at full speeds of nearly 34 knots, as fast as they could be driven, a dozen destroyers were tearing for the area of “No Man’s Sea” between the opposing squadrons. It was a chance vouchsafed to few destroyer officers, and then only once in a lifetime. They had started on the most exciting race in the world, a race towards the enemy, a race which had as its prizes honour and glory - possibly death. Almost as soon as our destroyers moved out to attack, 15 enemy destroyers, accompanied by a light-cruiser, the Regensburg, emerged from the head of the German battle-cruisers to deliver an attack upon our battle-cruisers. The British destroyers steered at full speed for a position on the enemy’s bow whence to fire their torpedoes, their course gradually converging on that of the German flotilla. At 4.40 the Nestor, Commander Bingham, followed by the Nicator, Lieutenant Jack Mocatta, and the Nomad, Lieutenant-Commander Paul Whitfield, swung round to north to fire their torpedoes, and also to beat off the enemy’s destroyer attack. These three ships were followed at intervals by the Petard, Lieutenant-Commander E. C. O. Thomson, and the Turbulent, Lieutenant-Commander Dudley Stuart. Immediately the Nestor, Nicator and Nomad turned in to attack the enemy’s light-cruisers, the German flotilla turned to an appropriately parallel course. Almost at once the destroyer fight started at a range of about 9,000 yards. Both sides fired rapidly as the distance decreased, and to onlookers the opposing flotillas were only seen as lean black shapes pouring smoke from their funnels as, with their guns blazing, they tore at full speed through a welter of shell-splashes. At about 4.45 the Nomad was hit in the engine-room, the explosion killing or wounding many men and destroying steam-pipes. At full speed, the Nestor and Nicator, followed at an interval by the Petard and Turbulent, and supported by the other destroyers, engaged the enemy flotilla at a distance which eventually dropped to about 600 yards - almost point-blank range. The Germans were outgunned, and in a very few minutes their attack was beaten off. Leaving two sinking ships behind them, and with several more hit and damaged, they made at full speed for the comparative safety at the head and tail of their battle-cruisers, closely pursued by our craft. The enemy had actually fired 12 torpedoes at the British battle-cruisers, though, thanks to our destroyers onslaught, they had been unable to approach within a range that gave them much chance of hitting. The Nestor and Nicator each fired two torpedoes at the enemy’s battle-cruiser line at a range of about 5,000 yards, while continuing to engage the German destroyers. The torpedoes missed, for, seeing the tell-tale splashes as they left their tubes, the German Admiral turned his ships away. The Petard, firing three torpedoes later at a range of about 7,000 yards, was luckier, for one of hers hit the Seydlitz, tore a hole 13 by 39 feet under her armoured belt, and put one heavy gun out of action. Swinging round to the eastward, followed by the solitary Nicator, the Nestor found herself rapidly approaching the head of the enemy battle-cruiser line, all four ships of which were soon pouring in a withering fire from their secondary armaments. The sea vomited splashes and spray fountains; but, pressing home his attack, Bingham fired his third torpedo at a range of about 3,500 yards. Throughout this period both the Nestor and Nicator were escaping destruction by a few inches, for the shell was falling all round them. According to one of Nicator’s officers, that ship avoided being hit by altering course towards each salvo as it fell, thereby confusing the enemy’s spotting corrections. “Throughout the whole action,” says the same officer, “the captain [Mocatta] was leaning coolly against the front of the bridge smoking his pipe, and giving orders to the helmsman.” His work done, Bingham still followed by the faithful Nicator, swung round through 180 degrees and made off at full speed to the westward to rejoin the British battle-cruisers, which, at 4.40, having sighted the approaching High Seas Fleet, had altered course to the northward. Here there occurs a slight discrepancy between the official reports of the Nestor and Nicator. Mocatta states that during the run back both ships were subjected to a very heavy fire at a range of about 3,000 yards from the leading battleships of the High Seas Fleet. Bingham says nothing of the batt...

The poignant Great War D.S.O. group of four awarded to Flight Lieutenant C. W. Graham, Royal Naval Air Service, a pioneer scout pilot in No. 1 Wing at Dunkerque who downed ‘a large German seaplane’ off the Belgian coast in December 1915; he was killed in September 1916, when, having taken off on an operational patrol from Great Yarmouth, his Short 184 Seaplane dived into the sea from 200 feet, the impact exploding his bomb load Distinguished Service Order, G.V.R., silver-gilt and enamels, with integral top riband bar; 1914-15 Star (Flt. S. Lt. C. W. Graham. R.N.A.S.); British War and Victory Medals (Flt. Lt. C. W. Graham. R.N.A.S.) together with Memorial Plaque (Charles Walter Graham) generally extremely fine (4) £5,000-£7,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- D.S.O. London Gazette 24 February 1916: ‘For his services on 14 December 1915, when with Flight Sub. Lieutenant Ince as observer and gunner he attacked and destroyed a German seaplane off the Belgian coast.’ Charles Walter Graham was born at St. Helier, Jersey on 12 November 1893, the son of Charles Knott Graham and his wife Helen. He was educated at Merchant Taylors’ School, where he excelled as a gymnast and fostered an interest in engineering. Shortly after leaving school, in 1913, he won the private owners’ prize and gold medal in the Warwickshire Club’s 100-Mile Open Motor Cycle Event. He was at Stuttgart when war broke out in August 1914 but managed to get home via Switzerland, following which he took up aviation at Hendon and qualified for his Royal Aero Club certificate (No. 2238) in a Grahame-White biplane on 12 February 1915; he also collected Third Prize in an “Impromptu” Speed Contest held there on 5 April 1915. A week later, Graham obtained a commission as a Temporary Flight Sub. Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Air Service and was posted to No. 1 Wing at Dunkerque, where he became a pioneer scout pilot. On 14 December 1915, flying Nieuport 3971, with Flight Sub. Lieutenant Ince as his Observer, he attacked and shot down ‘a big German seaplane’ off La Panne: ‘A merchant vessel was stranded on the sandbank near the Whistle Buoy on the 12th, owing to stormy weather, and was unable to be towed off. At 10 a.m. a report was received that two German Aviatiks were attacking her with bombs. Machines were sent out, and from 10.30 a.m. onwards, a continuous patrol was maintained, all hostile machines being driven off. At 3.15 p.m. on the 14th Flight Sub.-Lieutenant B. (sic) Graham, with Sub.-Lieutenant Ince as observer, in a Nieuport Scout, which was much faster, gave chase, and got within 100 yards’ range, the position being practically over the steamer. Flight Sub.-Lieutenant Graham dived and manoeuvred his machine so as to enable his passenger to train his gun upwards under the enemy’s tail at fifty tards’ range. This manoeuvre was repeated altogether three times, a number of rounds being fired into the enemy on each occasion. Upon the third occasion, when five rounds had been fired, the hostile machine suddenly turned sharply down, nose-dived vertically into the water, and was observed to be a flaming wreck. The pilot then vol-planed down to investigate more closely; his engine failed to pick up, and he was forced to descend into the sea close to the paddle minesweeper Balmoral. The Nieuport turned over on striking the water, and Flight Sub. Lieutenant Graham had great difficulty in releasing his belt under water and extricating himself. Eventually both he and his observer got clear, and within a few minutes the Balmoral had lowered a boat and with great promptness rescued the two officers.’ (The Dover Patrol, refers). A confidential report on his services was submitted on 22 December 1915: ‘Exceptional skill and courage. Has been continually employed on reconnaissance work and hostile aircraft patrols over the enemy’s lines. Specially recommended for promotion.’ He was indeed promoted to Flight Lieutenant in January 1916, shortly before the announcement of his well-deserved D.S.O. On 8 February 1916, Graham was seriously injured in a flying accident, following engine failure. He was admitted to the R.N.H. Haslar with ‘severe injuries to head, concussion and possibly base fracture of skull’ and there he remained until discharged on sick leave on 14 March 1916. In the interim, on the 15 February, the Vice-Admiral Dover Patrol mentioned Graham in despatches ‘for continuous meritorious service over the enemy’s lines’ and recommended him for special recognition and reward. His service record further states that he was still unfit to be medically re-surveyed in mid-April 1916, followed by the tragic news that he had been killed flying a Short 184 Type Seaplane (No. 8385) on 8 September 1916. Having taken off on an operational patrol from Great Yarmouth, his aircraft dived into the sea from 200 feet, the impact exploding his bomb load. It took two weeks to recover the wreckage and his body, his father taking possession of the latter on 27 September 1916. Just 23-years-old, Graham was buried in the Old Cemetery at Barnes, London, near where his parents were living at the time. Sold with an impressive array of awards for Gymnastics at Merchant Taylors’ School, comprising a winner’s cap, in velvet, with silver-wire embroidered ‘MTS’ motif, ‘Gymnasium’ and the dates ‘1910’, ‘1911’ and ‘1912’; a prize medal, in bronze, the obverse with school motto and crest, and reverse engraved ‘Gymnastics’ and ‘C. W. Graham, June 1907’, in its fitted Kenning & Son case of issue; together with others identical (2), but in silver, these named and dated ‘1911’ and ‘1912’, and in fitted Kenning & Son, London cases of issue; and his London Aerodrome Hendon prize medal for Third Place in the “Impromtu” Speed Contest, bronze, the obverse engraved, ‘Won by C. W. Graham, April 5th 1915’, 50mm. diam., in its fitted red leather Elkington & Co. Ltd. case of issue. Also sold with a copy Freedom of the City of London certificate, in the name of ‘Charles Walter Graham, son of the late Charles Knott Graham, Citizen of London and Merchant Taylor’, and Buckingham Palace forwarding slip for his memorial plaque.