A BOWIE KNIFE, JOSEPH RODGERS & SONS, NO. 6 NORFOLK STREET, SHEFFIELD, LATE 19TH CENTURY with single-edged fullered blade formed with a false swage, rectangular ricasso stamped with the maker’s details including cross and star mark, iron guard, German silver pommel and natural staghorn grip, in leather scabbard, 25.0 cm blade LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 261. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

We found 239713 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 239713 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

239713 item(s)/page

A FINE BOWIE KNIFE, JOSEPH RODGERS & SONS, CUTLERS TO HER MAJESTY, LAST QUARTER OF THE 19TH CENTURY with broad blade formed with a clipped-back point, struck with the maker’s details, the royal letters ‘VR’ divided by a crown and star and cross mark on one face, the reverse etched ‘Never draw me without reason’ and ‘nor sheath me without honour’ (faint in places), oval German silver guard, and chequered horn scales retained by three rivets, in its leather scabbard with German silver locket and chape and belt loop with vacant German silver escutcheon, 15.3 cm blade LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 265. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A BOWIE KNIFE, JOSEPH RODGERS & SONS, NO. 6 NORFOLK STREET, SHEFFIELD, EARLY 20TH CENTURY with tapering blade formed with a clipped-back point, rectangular ricasso stamped with the maker’s details including cross and star mark and the Royal letters ‘ER’ divided by a crown, German silver guard with globular terminals, natural staghorn scales, vacant German silver escutcheon in its German silver-mounted leather scabbard with belt loop, 20.2 cm blade LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 261. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A BOWIE KNIFE, JOSEPH RODGERS & SONS, NO. 6 NORFOLK STREET, SHEFFIELD, EARLY 20TH CENTURY with tapering blade formed with a spear point, rectangular ricasso stamped with the maker’s details including cross and star mark and the Royal letters ‘GR’ divided by a crown, German silver oval guard, natural staghorn scales, in its leather scabbard with belt loop, embossed ‘H. Hidden’, 17.5 cm blade LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 261. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A MASSIVE KNIFE FOR EXHBITION, JOSEPH RODGERS & SONS, NO. 6 NORFOLK STREET, SHEFFIELD, LATE 19TH CENTURY with strongly tapering blade engraved ‘The Camp Knife’ in capitals, signed in full and with star and cross mark on one face, formed with a scrolled fluted back-edge and recessed at the ricasso, engraved silver-plated hilt of derived scimitar form decorated with flowers and foliage (losses) and gutta percha grips, 64.5 cm overall LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 102. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A FIXED-BLADE CAMPAIGN KNIFE, JOSEPH RODGERS & SONS, CUTLERS TO HER MAJESTY, LATE 19TH CENTURY, POSSIBLY MADE FOR PRESENTATION BY ALBERT EDWARD, PRINCE OF WALES AND LATER KING EDWARD VII (1841-1910) with fixed blade with clipped-back point and filed back-edge, struck with the maker’s details, ‘VR’ divided by a crown, and star and cross, with four folding elements including corkscrew, button hook and awl, further accessories including tweezers, pincers, scissors and pricker concealed in the German silver pommel, the latter engraved ‘1875’ and ‘AE’, chequered horn scales, in its German silver-mounted leather scabbard engraved ‘AE’ ‘1875’ and with the crowned Most Noble Order of the Garter on the locket, with a loop for suspension, 22.0 cm overall (the knife) LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 97. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A HUNTING KNIFE, JOSEPH RODGERS & SONS CUTLERS TO HER MAJESTY, SHEFFIELD, CIRCA 1860 with tapering blade formed with a spear point, stamped with the maker’s details on one face, and ‘The Hunter’s Companion’ in script, rectangular ricasso struck with star and cross mark, German silver hilt comprising recurved quillons with flattened scrolling terminals, cap pommel (fitted with later copper alloy oval), and spirally-bound fishskin-covered grip, in its leather scabbard with German silver chape and locket, the latter with a belt hook, 23.5 cm blade LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 262. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A HUNTING KNIFE, JOSEPH RODGERS & SONS CUTLERS TO HER MAJESTY, SHEFFIELD, CIRCA 1860 with tapering blade formed with a false swage, engraved ‘The Hunter’s Companion’ in script, rectangular ricasso stamped with the maker’s details and star and cross mark, iron cross-guard, German silver small ferule, and shaped chequered grip, in its leather scabbard with German silver locket and chape, the former with an iron spring catch, 20.4 cm blade LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 262. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A SMALL DIRK, JOSEPH RODGERS & SONS, CUTLERS TO THEIR MAJESTIES, NO. 6 NORFOLK STREET, SHEFFIELD, CIRCA 1880 with double-edged polished blade of diamond section swelling towards the point, stamped with the maker’s details including cross and star mark on one face, German silver recurved guard, mother-of-pearl grip. In its German silver-mounted leather scabbard and in fine condition throughout, 13.0 cm blade LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 259. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A SMALL DAGGER, RODGERS, CUTLERS TO HER MAJESTY AND ANOTHER, UNSIGNED, LATE 19TH CENTURY the first with tapering double-edged blade, signed ricasso with star and cross mark, German silver hilt comprising straight guard with globular terminals, and beadwork grip, in associated scabbard; the second with tapering double-edged blade German silver beadwork hilt, and a pair of staghorn scales, in its leather scabbard, the first: 13.5 cm (2) LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, pp. 298 and 303. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A DIRK BY JOSEPH RODGERS & SONS, CUTLERS TO THEIR MAJESTIES, NO. 6 NORFOLK STREET, SHEFFIELD, LAST QUARTER OF THE 19TH CENTURY with tapering blade formed with a false swage point and struck with the maker’s details including cross and star mark on one face, rectangular ricasso formed with two pairs of small notches, moulded ferrule, German silver pommel, spirally carved horn grip bound with plaited copper alloy wire, leather scabbard with large German silver chape and locket, the latter with belt hook, 15.5 cm blade LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 265. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

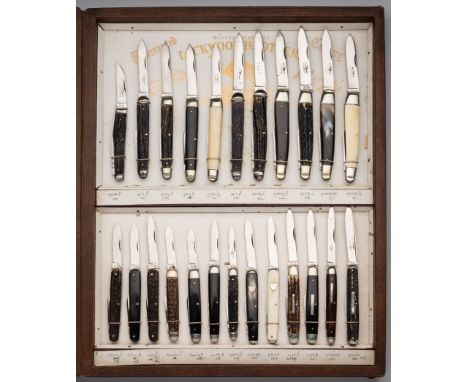

A CASED SET OF CARVING KNIVES, JOSEPH RODGERS & SONS, CUTLERS TO HIS MAJESTY, SHEFFIELD, EARLY 20TH CENTURY AND ANOTHER comprising knife struck with maker’s details, crown dividing the royal initials ‘GR’, and ‘Shear steel', natural staghorn grip, and nickel silver pommel, fork and steel en suite in its leatherette case lined in blue with the maker’s detail inside the lid in gilt letters; the second, T. Glossop, Sheffield, similar, in its mahogany case, the first case 41.5 cm (2) LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 192. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.