We found 239713 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 239713 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

239713 item(s)/page

A mid 19th Century portrait miniature of a young lady in period costume and wearing a multi-strand pearl necklace, painted on ivory, signed 'HK' lower right under convex glass in an ornate gilt metal frame, 6 x 5 cm excluding suspender, (Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) registered. Not available for export)

A William IV silver melon teapot, with relief embossed and chased floral decoration, flowerhead knop, scrolled acanthus leaf handle with ivory insulators, Edward, Edward Junior, John & William Barnard, London 1830, height 14cm, 25.4oz. This item has been registered as exempt from the UK Ivory Act 2018 on account of it being made before 3rd March 1947 with less than 10% ivory by volume. Ivory declaration submission reference 4ND2SBH91 lobe on body has a small dent otherwise no damage or repair, light wear to high points, hinge lid working perfectly, hallmarks clear

A Victorian matched three piece Aesthetic silver tea service to include teapot, sugar bowl and milk jug, each body engraved with Asian scene depicting pagodas and building by riverscape, three figures crossing a bridge, boat, birds and foliage, the reverse side with large crest within floral wreath cartouche, geometric banding to upper and lower sections, the teapot with bone handle and finial, hallmarked by Thomas Smily, London, 1868; the sugar bowl and milk jug hallmarked by The Goldsmith's Alliance, London, 1877, retailers stamp to bases, approx gross weight 43.56 ozt (1355 grams) together with two napkin rings and a pair of ornate teaspoons, all hallmarked, 2.43 ozt (75.3 grams) Further details: marks clear, bone handle loose in setting This item is offered for sale in accordance with the Ivory Act 2018 and has been assigned Submission Ref No. XYEVAKG3

A pair of early 20th Century Coalport two handles vases and covers, shape no: 7586, cobalt blue ground the central panels painted with titled scenes by E D Ball "Loch Doon & Loch Ewe., ornate gilt decoration to ivory ground collars and feet., green factory stamp and gilt painted: V7586D - 3rd 186, the cover with pagoda finials, 27cm high Further details:

A matched Scottish George IV three piece tea service comprising teapot, sugar bowl and milk jug, boat shaped engraved with flowers and foliage, with cast floral borders, on four foliage and paw feet, the teapot with acanthus thumbpiece, gilt interiors, hallmarked by William Marshall, Edinburgh, 1821, the teapot 1820 gross 48.57 ozt (1510.6 grams) This item is offered for sale in accordance with the Ivory Act 2018 and has been assigned Submission Ref. No. NADZ1V3N

A Royal Worcester blush ivory ewer, shape no: 789, shield shaped body painted with cattle drinking in river landscape within gilt cartouche framing, the reverse with thistles and wild flower bouquet, the handle with grotesque fish and Green Man mask terminals, the collar with blue enamel oval decoration, green factory marks, date code circa 1900, 44cm high overall

A Royal Worcester large blush ivory pot pourris, lid and domed cover, of lobed tapered form, decorated with flowers, gilt moulded strapwork to collar, the coronet style cover with pierced sand green glaze sections, gilt heightened, puce factory mark, shape no: 1312, Rd No: 112589, impressed marks, date code for 1897, approx 26cm high overall (3)

A Royal Worcester blush ivory large urn shaped ewer, shape no: 1309, decorated with wild flowers including poppies, wheat sheaves, insects and butterflies, signed with artist's monogram ER., with gilt heightened acanthus scroll handle, stepped circular foot, puce factory marks, date code circa 1893, Rg No: 111573, impressed marks and artist's initials, 42cm high overall Further details:

A matched pair of Royal Worcester blush ivory two handled pedestal bowls, boat shaped bodies painted with pink roses and foliage, signed by S Pilsbury, a single pink rose to interior, with gilt acanthus leaf handles, fluted socle above four grotesque marks and spreading circular bases, puce factory marks, shape no: H 194, date code for 1926 and 1928, approx 18cm at highest point (2) Further details:

Two Royal Worcester blush ivory pieces to include: a double ended vase, modelled as a piece of bamboo with shaped bamboo handle and leaves to body, gilt heighted, factory stamp, shape no: 858 and date code for 1907, approx 20cm long overall together with a two handled posy vase, painted with flowers, shape no: 982. date code for circa 1899, 17cm high (2)

Attributed to Albrecht Durer (1471-1528)The peasant and his wife at market, 1519engraving - black on ivory paper, 11.5 x 7cm, framed and glazed Further details: damage to paper upper section (tears at date and faces - see photographs), artist's monogram scratched / lacking from the boulder lower right section

A Victorian Aesthetic silver four piece tea service including tea pot, coffee pot, sugar bowl and milk jug, all with profusely engraved scroll work and geometric work, each with cartouche engraved with initials, the tea pot having script "Presented to John Popplewell by the congregation of Holy Trinity Church Bradford on the completion of 20 years of most zealous and efficient voluntary service as choirmaster, December 15th 1884" to side, all hallmarked London by Josiah Williams & Co, the tea pot and coffee pot dated 1883 and sugar bowl and milk jug for 1882. All within an original rectangular wooden and felt lined chest, with brass carry handles and two drawers to inside. With key. Weight approx. 2380.6 grams (76.5ozt)Further details: The service is in clean, good condition. The case being worn, slightly damaged to edges commensurate to age, scratched and possibly re-lined to inside. This item is offered for sale in accordance with the Ivory Act 2018 and has been assigned Submission Ref No. MKW3JCJA

A Victorian silver coffee pot, baluster shaped body engraved with lambrequins, geometric decoration and vacant quatrefoil cartouches, chased ornate pelmet border to upper section of body on four ornate scroll feet, domed cover with baluster finial, hallmarked by George Richards, London, 1854, numbered 3789, approx 29.95 ozt (931.7 grams), approx 26cm high overall Further details: marks clear to undersideThis item is offered for sale in accordance with the Ivory Act 2018 and has been assigned Submission Ref No. WZLMUSBY

ABDOULAYE DIARRASSOUBA 'ABOUDIA' (B. 1983)Untitled circa 2017 signedacrylic, spray paint, oil stick and paper collage on canvas149 by 149 cm.58 11/16 by 58 11/16 in. This work was executed in circa 2017. Footnotes:ProvenanceGalerie Santa Maria, Ivory Coast Private Collection, SwitzerlandAcquired from the above by the present ownerThis lot is subject to the following lot symbols: ** VAT on imported items at a preferential rate of 5% on Hammer Price and the prevailing rate on Buyer's Premium.For further information on this lot please visit Bonhams.com

ABDOULAYE DIARRASSOUBA 'ABOUDIA' (B. 1983)Untitled circa 2017 signedacrylic, spray paint, oil stick and paper collage on canvas98.9 by 99.8 cm.38 15/16 by 39 5/16 in.This work was executed circa 2017.Footnotes:ProvenanceGalerie Santa Maria, Ivory Coast Private Collection, SwitzerlandAcquired from the above by the present ownerThis lot is subject to the following lot symbols: ** VAT on imported items at a preferential rate of 5% on Hammer Price and the prevailing rate on Buyer's Premium.For further information on this lot please visit Bonhams.com

˜ AN AMERICAN SKINNING KNIFE, ONTARIO KNIFE CO., USA, EARLY 20TH CENTURY, AND SIX FURTHER SKINNING TRADE KNIVES, 20TH CENTURY the first with signed blade and hardwood grip stamped ‘Old Hickory’, in its leather scabbard; the second inscribed ‘Bushman’s friend’ in a scroll on the blade, with ivory-mounted steel, in its leather scabbard; the third stamped ‘Lockwood Brothers’ and ‘Pampa’ on the blade, in its leather scabbard stamped en suite; the fourth by the same, in its leather scabbard; three further knives, similar, by I. Wilson, ex Syracuse St., Sheffield, with wooden grips impressed ‘Hudsons Bay Company 1870’, the first: 15.7 cm blade (7) LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, pp. 245-246. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

˜ AN EXCEPTIONAL HUNTING DAGGER OF PRESENTATION QUALITY, BROOKES & CROOKES, SHEFFIELD, WITH SILVER-MOUNTED SCABBARD, H. W. & L. DEE, LONDON 1877 with heavy polished blade formed with a slender fuller on each face and with knurled back-edge, etched on one face with a frosted panel filled with a hunting scene involving three elephants with howdahs, scrolling foliage, and the maker’s details with bell symbol within an oval, rectangular ricasso, shaped thick silver-plated iron cross-guard with knurled border en suite with the blade, silver-plated tang (silver with small losses), brass fillets, and a pair of ivory grip-scales retained by five rivets, each carved with finely detailed Prince of Wales’ feathers issuant from a crown at the pommel, in its original wooden scabbard encased in tooled leather decorated with large panels of trellis (small losses and minor damage), with engraved silver locket and chape, each engraved with a symmetrical design of scrolling flowers and foliage, and the locket complete with a ring for suspension, 33.0 cm blade LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 98. The present knife was probably made as an exhibition piece with a view to winning Royal commissions, subsequent to the Prince of Wales’s tour of India in 1875-6. Brookes & Crookes was established in 1858 by two Nonconformists, John Brookes (1825-1865) and Thomas Crookes (1826-1912). In their founding year the partners entertained their employees with a day of cricket and toasting, where Brookes underlined their intention to produce first-class goods and Crookes promised fair remuneration for labour. Though common sentiments at the time, Brookes and Crookes were already known for paying bonuses for new designs. Sadly, the partnership was short-lived as Brookes died from apoplexy at West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum, near Wakefield, on 14 February 1865 aged only 39 years. Crookes took over the business helped by his works manager William Westby who moved with his family to the factory at Atlantic Works in 1861. The ‘Bell’ trade mark became a badge of excellence and they were famed for the variety of their sportsman’s and multi-blade knives. A UK Ivory Act 2018 certificate for this lot will be made available to the purchaser Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

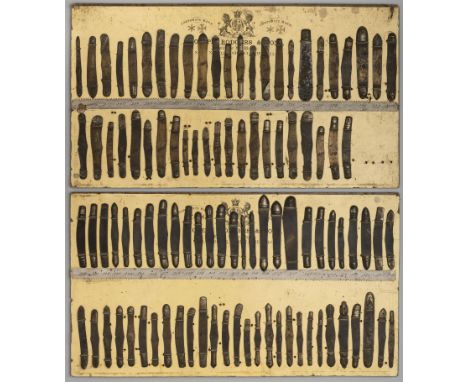

˜ AN EXCEPTIONAL DISPLAY OF TWELVE MINUTE PAIRS OF SCISSORS, SHEFFIELD, 19TH CENTURY, PROBABLY JOSEPH RODGERS & SONS the scissors of burnished steel, mounted on a pad on a balance of finely chiselled burnished steel, the opposing balance with a single small square weight, all mounted on a blue velvet base with an ivory shield-shaped escutcheon inscribed ’12 pairs of perfect scissors which weigh only half a grain’, complete with a tortoise-shell mounted angled magnifying glass, on a moulded wooden stand with bun feet and glass dome cover, the scissors approximately 2.5 mm overall ProvenanceStated by the vendor to have been part of the celebrated displays at Joseph Rodgers & Sons showrooms at 9 Norfolk Street. LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 88. Joseph Rodgers & Sons LtdIn the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A FINE AND VERY RARE SMALL BARREL POCKET KNIFE, JOSEPH RODGERS, MAKERS TO HIS MAJESTY, NO. 6 NORFOLK STREET, SHEFFIELD, LATE 19TH CENTURY with four small folding blades of differing form at each end, German silver fillets, and four turned moulded mother-of-pearl scales, each retained by a rivet top and bottom, in a French leather-covered case, probably original, 8.0 cm (closed) LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 119. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A LARGE SPORTSMAN’S OR COACHMAN’S KNIFE, RODGERS, CUTLERS TO HIS MAJESTY, 6 NORFOLK STREET, LATE 19TH CENTURY AND ANOTHER, JOSEPH ELLIOTT & SONS, SHEFFIELD the first with eight folding elements including signed blades, farrier’s hook, scoop borer, corkscrew and cartridge extractor, milled copper alloy fillets, nickel silver body and loop; the second with six folding elements including signed blade, button hook, farriers hook and scoop borer, copper alloy fillers, nickel silver body and loop, the first: 12.7 cm (closed) (2) LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 154. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

˜ A PROPELLING PENCIL AND KNIFE FORMED AS A PERCUSSION MUSKET, RODGERS, CUTLERS TO HER MAJESTY, LATE 19TH CENTURY AND A CASED PAIR OF MINIATURE PENKNIVES the first with folding blade stamped by the maker and with cross marks at the ricasso, folding German silver propelling pencil, tortoiseshell veneered stock, and German silver details; the second comprising one knife with two folding blades and another with single folding blade, each with mother-of-pearl body, in lined padded case, the outside embossed Rodgers, Cutlers to his majesty’ in gilt letters, the first: 8.7 cm (closed) (2) LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 115. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

˜ THE MULTI-BLADE LOCKBACK SPORTSMAN’S POCKET KNIFE GIVEN BY CAPTAIN WELFIT AS A MARK OF ESTEEM AND APPROBATION FOR ORDERLY CONDUCT AND SOLDIER-LIKE APPEARANCE AT NEWARK. 8TH MAY 1847, JOSEPH RODGERS & SONS, 6 NORFOLK ST, SHEFFIELD, CUTLERS TO HIS MAJESTYwith signed single-edged spearpoint blade, signed paring blade, ivory blade with 4 in graduated ruler, propelling pencil, corkscrew, awl trace borer, main triangular awl, button hook, screwdriver, and farrier’s hook, the latter with presentation inscription, concealed toothpick, tweezers, and split folding tortoiseshell scales with surgical fleam, natural staghorn scales, German silver escutcheon engraved ‘Robert Tillotson’: in red Morocco leather lined case, probably the original, 14.5 cm (case) LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 85. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A FINE GOLD-MOUNTED PENKNIFE, JOSEPH RODGERS & SONS, 6 NORFOLK ST, SHEFFIELD, CUTLERS TO HIS MAJESTY, LAST QUARTER OF THE 19TH CENTURY with twelve folding blades and accessories, including bodkin, borer, hoof pick, and corkscrew, stamped with the maker’s details and mark of a star and cross, fitted with rounded mother-of-pearl scales retained by four gold-capped rivets, four finely engraved gold terminals, and vacant gold shield-shaped escutcheons, 11.3 cm (closed) ProvenanceStated to have been made for the Duke of Rutland. LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 78. Hayden-Wight states that an identical knife was made for Ulysses S. Grant, 18th President of the United States (1869-77). In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A SPORTSMAN’S 'WHARNCLIFFE' KNIFE, RODGERS, NO. 6 NORFOLK STREET, SHEFFIELD, CUTLERS TO HIS MAJESTY, EARLY 20TH CENTURY with folding blade stamped ‘Wharncliffe’, saw, corkscrew, awl, shaped farrier’s hook, inlet picker and tweezers, natural staghorn scales, brass fillets, and vacant German silver escutcheon, 10.4 cm (closed) LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p.84. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A SPORTSMAN’S KNIFE BY J. RODGERS & SONS, 6 NORFOLK STREET, SHEFFIELD, EARLY 20TH CENTURY AND FOUR POCKET KNIVES, JOSEPH RODGERS, SHEFFIELD, EARLY 20TH CENTURY the first with seven folding elements including signed blades, belt hook, farriers hook and corkscrew, nickel-silver scales and loop; the second to fifth each stamped with the maker’s details at the ricasso of the main blade, two with clipped-points and two with spear points, the first: 12.5 cm (closed) (5) LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, pp. 151 & 142. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A BUTLER’S KNIFE BY RODGERS, 6 NORFOLK STREET, SHEFFIELD, EARLY 20TH CENTURY AND TWO FURTHER KNIVES the first with four signed folding elements including the maker’s details and cross and star mark, and German silver body; the second W. Morton, Sheffield, with five folding elements including coach door key; and the third Richardson, Edinburgh with two folding elements comprising pen blade and pincers and horn scales, the first: 9.0 cm (3) LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 151. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

EIGHT LOCK KNIVES, JOSEPH RODGERS & SONS, NO. 6 NORFOLK STREET, SHEFFIELD, EARLY 20TH CENTURY signed on the blades and with the address details at the ricassi, five with a single blade and three with two blades, and each with natural staghorn scales, the longest: 15.5 cm (closed) (8) LiteratureDavid Hayden-Wright, The Heritage of English Knives, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2008, p. 135. In the nineteenth century, Rodgers had an unsurpassed reputation and history that was synonymous with the cutlery trade. The family's first cutler, John Rodgers (1701-85), is recorded around 1724, with a workshop near the present cathedral. In the same year the Company of Cutlers 'let' him a mark, a Star and Maltese Cross, which became world famous in later years. John Rodgers had three sons, John (1731-1811), Joseph (1743-1821), and Maurice (c.1747-1824) who joined the business and succeeded him. They are recorded with more workshops by 1780 and the business soon extended to occupy a nearby block of buildings at 6 Norfolk Street, an address that became as famous as Rodgers’ trade mark. By the early 19th century their trade had expanded from pen and pocket knives to include table cutlery and scissors. By 1817 the General Sheffield Directory lists the firm as ‘merchants, factors, table and pocket knife, and razor manufacturers’. In 1821 John’s son Joseph died and his sons continued the business under the leadership of the younger John (grandson of the founder). John was described as ‘unobtrusive in his manner’ but was ambitious and one of the founding partners of the Sheffield Banking Co. He had a flair for marketing and travelled the country taking orders. Not only was his firm’s output and range greater than any other Sheffield firm, but its quality was superior. The company’s manifesto states: ‘The principle on which the manufacture of cutlery is carried on by this firm is – quality first … [and] … price comes second’. He began making exhibitions knives and presented George IV with a minute specimen of cutlery with 57 blades, which occupied only an inch [25mm] when closed. In 1822, Rodgers’ was awarded its first Royal Warrant. Another fourteen royal appointments, from British and overseas royal dignitaries, followed over the next eighty years, and its company history was duly titled: Under Five Sovereigns. John Rodgers next commissioned the Year Knife, with a blade for every year (1821) and opened his sensational cutlery showroom in Norfolk Street where visitors came to marvel at Rodgers’ creations. Perhaps the greatest highlight shown there was the Norfolk Knife, an over 30 inch long sportsman’s knife with 75 blades and tools, that Rodgers’ produced for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The showroom proved particularly popular with Americans whose trade played a significant role in the firm’s expansion. Additionally, they looked East, with agents in Calcutta, Bombay, and Hong Kong by the mid-19th century. These markets enabled Rodgers to become the largest cutlery factory in Sheffield. The number of workmen appears to have grown from about 300 in the late 1820s, to over 500 in the 1840s. In 1871 the business became a limited company with Joseph Rodgers (1828-1883), grandson of the Joseph Rodgers who had died in 1821 and Robert Newbold as managing directors. Joseph died on 12 May 1883 and Newbold became the chairman and managing director. The firm continued to expand with offices in London, New York, New Orleans, Montreal, Toronto, Calcutta, Bombay and Havana. Their work force in 1871 was around 1,200 and accounted for one-seventh of all Sheffield’s American cutlery trade. In 1876 the American market was stagnating and Rodgers’ began looking elsewhere with a focus on trade in the Middle East, India and Australia. Notably the name ‘Rujjus’ or ‘Rojers’ was said to have entered the language as an adjective expressing superb quality in Persia, India and Ceylon. By 1888, the value of Rodgers’ shares had more than doubled and, in 1889, a silver and electro-plate showroom was opened in London. At this time, Rodgers acquired the scissors business of Joseph Hobson & Son. Rodgers’ produced catalogues that were packed with every type of knife imaginable. Pocket knives were made in scores of different styles. Ornate daggers and Bowie knives and complicated horseman’s knives were made routinely. Some patterns, such as the Congress knife and Wharncliffe knife, were Rodgers’ own design. The Wharncliffe – with its serpentine handle and beaked master blade – was apparently designed after a dinner attended by Rodgers’ patron Lord Wharncliffe. The firm’s workmanship was usually backed by the best materials. Rodgers’ ivory cellar in Norfolk Street was crammed with giant tusks and was regarded as one of the hidden sights of the town. Four or five men were constantly employed in sawing the tusks, and around twenty four tons of ivory were used a year around 1882. Rodgers’ appetite for stag was no less insatiable: deer horns and antlers filled another cellar and pearl from the Philippines and was also cut there. Around 1890, Rodgers’ began forging its own shear steel and in 1894 they began melting crucible steel. Newbold retired in 1890 and the grandsons of Maurice Rodgers, Maurice George Rodgers (1855-1898) and John Rodgers (1856-1919), became joint-managing directors. The McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 halved their American business and consequently they toured South Africa. Despite increasing foreign competition and the decline of the American market, Rodgers’ prospered before the First World War. However, workers’ wages were cut while the partners continued to take significant dividend which culminated in a prolonged and bitter strike. The First World War saw a decline in the business which continued steadily until the 1975 when it was absorbed by Richards and ceased trading in 1983. Joseph Rodgers & Sons left an enduring legacy in its knives. Its dazzling exhibition pieces and other fine cutlery show that the company’s reputation as Sheffield’s foremost knife maker was well founded. Abbreviated from Geoffrey Tweedale 2019. Part proceeds to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.