14th century AD. A pewter pilgrim's badge representing the consecration of the Benedictine monastery in Einsiedeln, Germany, by Bishop Konrad of Constanta; pentagonal plaque with four fixing loops; Mary crowned and robed holding the infant Jesus sitting within a building with shingle roof and tower enclosing a standing bell-ringer holding two ropes; approaching figure outside with bishop's mitre and sceptre followed by a robed and winged angel holding a voided orb(?); blackletter inscription to the frame '* die * wicht * got * selb * mit * englen + dis * ist unser * frowen * cabell * reichen * von * ueisidelen*'. 18.5 grams (188 grams total), 73mm (3"). From an important private family collection; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent. This scene commemorates the consecration of the Benedictine monastery in Einsiedeln by Bishop Konrad of Constanta. On the night of 13th September 948 AD, the consecration of this chapel was to be ordained by Christ himself and his angel, and the bishop after arriving the next day at the temple heard the words 'Stand away, brother, God himself ordained the chapel'. In the literature on the subject, the characters described above are known as 'the type of ordination of an angel' (German: Engelweihe) and appear repeatedly in the form of casts on 15th century church bells. At the end of the 14th century Einsiedeln was one of the most important pilgrimage centres, where the first miracle was recorded in 1388 AD. Very fine condition.

We found 596780 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 596780 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

596780 item(s)/page

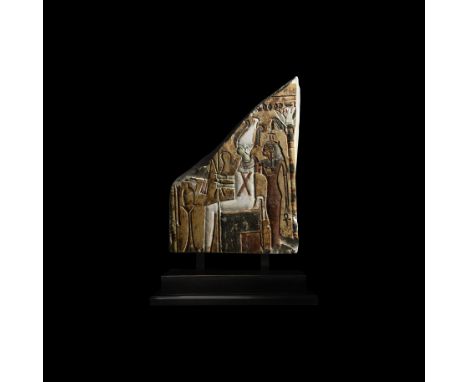

19th-20th Dynasty, 1189-1077 BC. A limestone relief section, curving to the right hand side; to the lower left the figure of Osiris, mummiform body, skin with green pigment, wearing Atef crown, Broad Collar, crossed over sash to the front; hands extended holding crook, flail and sceptre, seated on a throne; to the front an offering table with vase; behind the standing figure of the goddess Ma'at as Lady of the West, wearing tripartite wig, Broad Collar, close fitting dress; headdress with band across brow, ostrich feather plume to the top; both figures within a naos shrine, roof supported by lotus flower columns; mounted on a custom-made stand. 8.3 kg total, 33.6cm with stand (13 1/4").Property of a gentleman living in central London; formerly in the collection of the famous French Egyptologist, Alexandre Varille (1909-1951); thence by family descent until 2015. Alexandre Varille was from a cultured family from Lyon. While he studied Economics, he met Victor Loret, his Egyptology professor at the University of Lyon, and followed him in his devotion to Egyptian philology and archaeology. Varille began working in Egypt in 1931 together with his colleague Clément Robichon (1906-1999), and the following year he was made a member of the Institute Français d'Archéologie Orientale in Cairo. In 1939 he excavated the gates of Ptolemy III and Ptolemy IV from the temple of Medamud, now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon. He wrote his thesis in Egyptology on an important Egyptian functionary of the New Empire, Inscriptions concernant l'architecte Amenophis, fils de Hapou, published by Jean Vercouter, IFAO, 1968. He dedicated his first publication about Karnak (IFAO, 1942) to Schwaller de Lubicz. He only returned to France for short periods to publish with Clément Robichon the book entitled En Egypte, then published late 1955, in New York. Eternal Egypt was translated from French by Laetitia Gifford. He died in a car accident in France in 1951 just after the presentation of his symbolic theory at the French Institute, section Academy of Sciences.Very fine condition, some restoration.

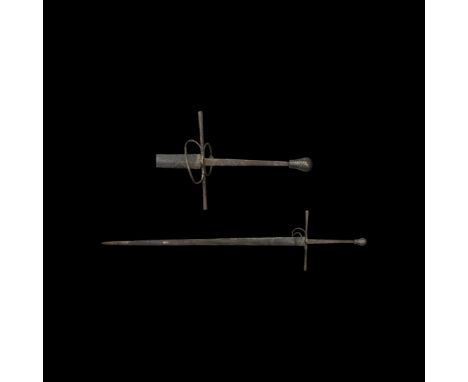

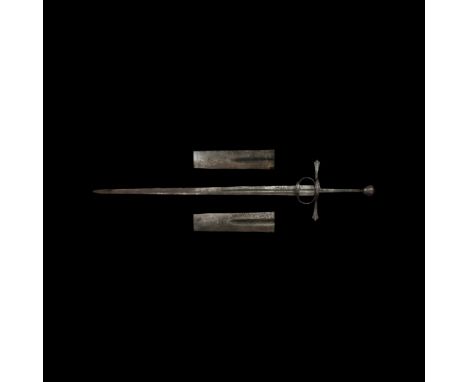

Mid 16th century AD. A German Renaissance 'hand-and-a-half' or 'Bastard' sword, with double ring guard, double edged broad blade; this gradually tapers towards its point; complex hilt, with pommel (style T5) pear-shaped, closed by a button on the top, very long tang, straight and circular cross-guard; the handle presents a double side guard on both sides and one additional ring on the lower part of the hilt, bowing towards the undecorated flat blade. See Fiore Furlan dei Liberi da Premariacco, Il fior di battaglia,Venezia /Italia /Padova, 1410, Ms. Getty inv. Ms. Ludwig XV 13 (83.MR.183); Oakeshott, E.,The sword in the Age of the Chivalry, Woodbridge, 1964 (1994); Dufty, A.R.,European Swords and daggers in the Tower of London, London, 1974; Talhoffer, H., Medieval Combat: a Fifteenth-Century Illustrated Manual of Swordfighting and Close-Quarter Combat, by Rector, M. (ed."). London, 2000; the sword has a good parallel with a German sword kept in the Tower of London, published by Dufty (1974, pl.14, lett.a), with which it shares identical characteristics, like the pear-shaped pommel. 1.5 kg, 1.27m (50").From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; believed from Liege, Belgium; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.The use of two hand swords was a typical way of fighting of the Gallic and Germanic tribes that, when facing the Roman legionaries they struck them from the top downwards, brandishing their swords with both hands. In fact, the chronicles report that the legionaries were intimidated by this brutal way of fighting and by the powerful blows that ensued ... even if this certainly did not prevent them from hitting their opponents with rapid and lethal strikes sheltered by their shields, how they were trained to do and how Vegetius describes. But the true genesis of such swords was due to the evolution of the use of armour in combat. It is logical to think that when, in 14th-15th century, a warrior faced an adversary covered by 30-40 kg of steel, the classic one-handed sword and its use lost a lot of meaning. The sword, thanks to the evolution of metallurgy, then began to change assuming the shape and characteristics that we attribute to those of the European two-handed sword. The first fencing text that has come down to us, of Italian origins, to describe the use of this weapon is the 'Flos Duellatorum' (1409 AD) written by the Master Fiore dei Liberi. Besides knowing that Fiore had studied, by his own admission, from the best German and Italian Masters, we know that at the time of writing his treatise he was already old; we can therefore assume that the way of fighting described by him may be the one used in Italy at least from the second half of the 1300s, but its importance lasted until the end of the 16th century as well. The Flos Duellatorum of Fiore dei Liberi (preserved in the Getty) is depicting two Magistri in Posta di Donna (woman’s position"). As regards the use of the sword with two hands Fiore distinguishes between the techniques to be used protected by a simple 'zupparello' (gambeson) and those to be used in complete armour (so much to dedicate a special 'chapter' with guards and techniques specific to this particular type of combat) demonstrating an efficacy, an expertise and capacity of an unexpected finesse, especially in the eyes of those who think of a way to fight based almost exclusively on powerful and brutal blows. However, this does not mean that surely in Fiore's game the physical force finds an important component and plays an undisputed role as well.Fine condition, repaired. Rare.

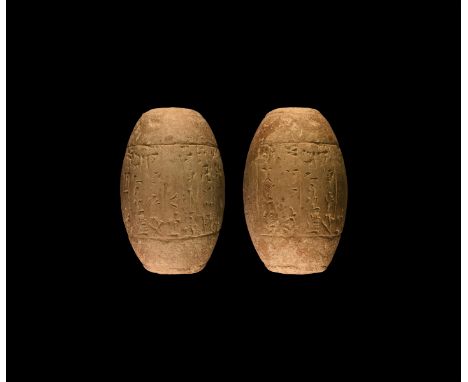

Third Dynasty of Ur, 22nd-21st century BC. A Mesopotamian cuneiform inscribed clay barrel cylinder, a scribal student’s trial piece, with excerpts from two different known texts: the first consisting of three long lines of text from end to end concerning Arad-Nanna, a well-known high official at the time of King Shu-Suen of Ur, reading ‘Arad-Nanna, governor of the Shimashkians and the land of Karda’; the second in a centered column extending more than half-way around the cylinder, with short lines (reflecting the lines of the original model text), reading ‘for (the god) Nanna, [king’s name omitted], the king of Ur, king of the Four Quarters, set up(?) a 5 mina (weight)'; pierced down the centre. 262 grams, 95mm (3 3/4"). From the Addis Finney (1908-1996) collection, a chemical engineer from Akron, Ohio, USA, who formed his collection in Basel, Switzerland, between 1935-1965. Fine condition.

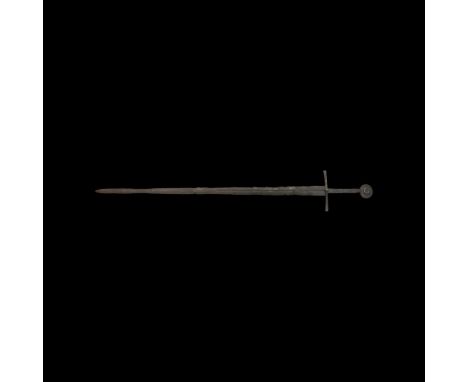

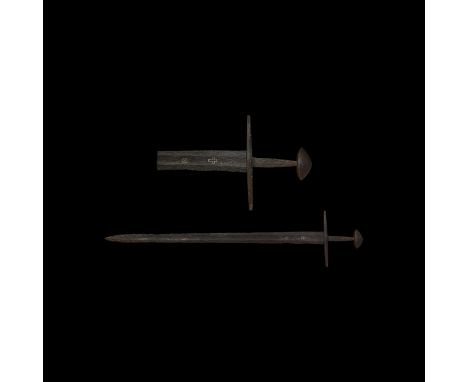

Early-late mid 14th century AD. A Western Middle Age iron longsword from Italy, of Oakeshott's Type XV.A, cross style 8, pommel style J (recessed); strongly tapering, acutely pointed blade of four-sided 'flattened diamond' section; the edges are straight, and taper without curves to the strongly reinforced point; strong signs of battle nicks along the edges to both sides that may have reduced the width of the blade; cross style characterised by the very solid écusson which grows naturally out of the two arms, tapering gradually outward to sharply down-turned tips; long grip with slight taper, disc pommel with chamfered edges, with gold inlay once probably indicating a heraldry, today lost; shiny brown patina, no serious pitting; nice example of a well employed sword, ideal for a weapon designed to deal powerful cutting and thrusting blows. See Oakeshott, R.E., The Archaeology of the weapons, London, 1960; Oakeshott, E., The sword in the Age of the Chivalry, Woodbridge, 1964 (1994); Oakeshott, E.,Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991; Oakeshott, E.,Sword in hand, London, 2001 (2007); many specimens recall our sword: but the most striking sample is the one from the Lake of Lucerna (Oakeshott, 2001 (2007), p.140); another extremely similar sword, although lacking the grip, was found in the Thames in London, and should still be in the collection of the Society of the Antiquaries at Burlington House in London; this can be dated with some certainty between about 1310 and 1340 AD, because it was found in the Thames when the foundations were being prepared in 1739 AD for Westminster Bridge, and evidently it fell into the river in its scabbard, so that when it was discovered, the three silver mounts of it were still upon its blade; these are exactly of the same type as on the sword of Can Grande Della Scala in Verona and that on the Berkeley effigy in Bristol (Oakeshott, 1960, pp. 308-309); others similar specimens are from a group exemplified by one in the collection of the late Sir James Mann, found in Northern France, another in Yorkshire, and yet another with an Arabic inscription which probably came from Italy; they vary a little in size, otherwise they seem almost identical (Oakeshott, 1964 (1994), p.59"). 1.1 kg, 1.05m (41 1/4").From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.Type XV seems first to have appeared in the second half of the thirteenth century. With type XV we come to a form of blade which does not seem to have been in use since the days of the short Roman gladius or the longer spatha of the Roman Empire. The general outline or silhouette of this type is much like that of the previous type XIV, but the section of the blade is different, as in the prime function of the sword. The type XIV was conceived and used when the main protective armour was mail, with or without metal, leather or quilted reinforcement, and it was primarily a hewing and slashing weapon. The type XV allowed the warrior to deliver a lethal thrust, also if the protection was completely made of metal plate. The blade XVa type was similar, though generally narrow and slender, to the general typology. The grip was much longer, from 7 to 9 or even 10. Forms of pommel and cross are the same as for Type XV. Many swords of this type, like our specimen, have long grips, like the war-swords of Type XIII. After about 1350 AD, nine swords out of ten seem to have such grips, and are today variously referred to as 'hand-and-a-half' or 'Bastard' swords. The latter term was used in the fifteenth century AD, but it is not certain that it was applied to this particular kind of weapon. 'Hand-and-a-half'', though modern, is a name more apt for it; these swords were single-handed weapons, but by being furnished with long grips, could at need, be wielded easily in both. All these hand-and-a-half swords have grips about 7 long, sharply tapering blades of four-sided section about 32 long, straight crosses tapering towards the tips, which are abruptly turned downwards and large pommels of Type J. Various military effigies and brasses of the period 1360-1420 AD, show swords like this one; there is only a limited variety in the forms of hilt, and the blades are long and slender. However, we cannot say for certain that they are of Type XVa, because they are sheathed; and many of the swords of Type XVII are of the same shape and proportions, but have a different blade-section. On English effigies of the second half of the fourteenth century AD, are many such swords; the best (and the best known) is at the Black Prince's side on his tomb at Canterbury; one almost identical is on the effigy of Lord Cobham (Oakeshott, 1960, fig.139"). In these effigies the cross is nearly always shown as a straight or slightly curved bar of square section, possibly because to portray the rather delicate down-turned tips would be difficult and over-fragile in stone. Type XV may seem to have been misplaced, for it continued in use for almost two centuries and was most popular after 1350 AD, yet the sub-type seems to have gone completely out of use within the second half of the 14th century. The reason being that Type XV began during the latter part of the 13th century, whereas XVI may not have come into use until just after 1300 AD.Fine condition, restored.

2nd century BC-2nd century AD. An iconic Pagan sculpture securely dated to the Irish Celtic Period of 200 BC-200 AD, this large and imposing carved sandstone head was modelled from a substantial hemispherical boulder; the elegantly simplistic facial features comprise convex lentoid eyes flanking a rectangular flat nose, above a horizontal slit mouth with a suggestion of cheeks; the current owner, James Moore, has written about the various scholars that viewed it prior to his acquisition at auction: 'the head was viewed prior to the auction by many people experienced in these matters. They included Dr Patrick Wallace, director of the National Museum of Ireland and his staff; Dr Richard Warner former director of the Ulster Museum; eminent archaeologist and author Dr Peter Harrison; Professor Etienne Rynne, author of Celtic Stone Idols in Ireland in the Iron Age in the Irish Sea Province (available on the web"). All of the above gave favourable opinions, concurring with Dr Lacy's view. I have in my possession an exhibition catalogue of Celtic stone sculpture with an introduction by Martin Retch held by Karsten Schubert & Rupert Wace Ancient Art Ltd. in London 1989. There were eleven stone heads in this exhibition but in my opinion none of them had the qualities / provenance of the Ballyarton Head'; provided with a custom-made iron hoop stand for display. See Ross, A. Pagan Celtic Britain, London, 1967 for overview of the iconography of pre-Christian Britain and Ireland; Rynne. E. Figures from the Past, Studies on Figurative Art in Christian Ireland in Honour of Helen M. Roe, Dublin, 1987. 63 kg, 46 x 36cm including stand (18 x 14"). From the private collection of James Moore; acquired from Whyte’s Auctions 23 April 2010, lot 1 (front cover piece); formerly the property of Mr Pinkerton, Castlerock, County Derry; found by his father in the 1930s while repairing a stone wall in the Ballyarton Area of Claudy in the Sperrin Mountains, County Derry, Northern Ireland; accompanied by: a hand-written letter of the owner discussing the piece and its history; a copy of the relevant Whyte’s Auction catalogue pages with report by Kenneth Wiggins (MIAI, BA and an MPhil in archaeology), archaeologist and author; an original copy of an article on the item in the Irish Times newspaper (dated 1 May 2010); an original photograph of the head by Pinkerton when sited in his garden in 1976, inscribed as such to the reverse; original hand written correspondence with Dr Brian Lacy, Director of the Discovery Program and of The New University of Ulster, dating it to the period 200BC to 200AD (dated 29 July 1976), original signed correspondence with Craig McGuicken of the Heritage & Museum Service for Derry City Council requesting a loan of the object for display at the Tower Museum (affiliated to the Ulster Museum of N. Ireland); and with an orginal letter from Matt Seaver of the Irish Antiquities Division, National Museum of Ireland, dated 8 November 2019, showing interest in acquiring the head but suggesting that it be offered to the Ulster Museum first who were under-bidders in 2010. The subject of the iconography of pre-Christian stone heads is explored in Ross (1967, p.115ff) alongside the difficulty of establishing accurate dating for this artefact type. Stylistically, the Irish group of stone heads demonstrate a simplicity and economy of line which suggest an origin in the Iron Age (Rynne, 1987"). Professor Rynne is one of the 'many people experienced in these matters' who had the opportunity to view the head before the Whyte's auction in 2010, alongside Dr. Patrick Wallace (director, National Museum of Ireland), Dr. Richard Warner (former director of the Ulster Museum) and Dr. Peter Harbison, the eminent archaeologist. The opinion of this group agreed with that of a previous researcher, Dr. Brian Lacy, who wrote to the then owner of the piece in 1976 that '[t]hese heads normally occur in craft schools and on the basis of this example [and another from Alla townland nearby] it may be possible to identify a 'school' in the Claudy area.' It was Lacy who suggested a date range '200 BC to 200 AD' for the head. Professor Ian Armit has written several books and papers on the significance of the 'severed head' motif in Celtic (Iron Age) culture. In Death, decapitation and display? The Bronze and Iron Age human remains from the Sculptor's Cave, Covesea, north-east Scotland, Cambridge, 2011; and later in Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe, Cambridge, 2012, he demonstrates that the human head carried symbolic associations with power, fertility, gender, and other social factors in the context of the Iron Age in Europe. The range of evidence for beheading and the subsequent curation and display of severed heads includes classical literary references, vernacular iconography and the physical, skeletal remains of the victims of this custom. The idea has arisen of a head-cult extending across most of Continental Europe and the islands of the North Atlantic including the British Isles. This notion is in turn used to support the idea of a unified and monolithic 'Celtic culture' in prehistory. However, head-veneration was seemingly practised across a range of Bronze Age and Iron Age societies and is not necessarily linked directly to the practice of head-hunting (i.e. curation of physical human remains"). The relations between the wielders of political power, religious authority and physical violence were more nuanced than a simple reading of the literary and physical evidence would suggest. The stone heads of Ireland are an enduring expression of this strong association between the human body and the numinous powers of the intellect. Fine condition. An important Irish antiquity, of a type very rarely in private ownership.

Early 14th century AD. A Western Middle Age iron longsword, possibly from Italy, of Oakeshott's Type XVI.2, cross style 2, pommel style K, showing a slender triangular blade with deep fuller and acute point; narrow lower guard with flared ends; on both sides along the edges strong signs of battle nicks, that have reduced the width of the blade; long grip with slight taper, disc pommel with chamfered edges, shiny brown patina, no serious pitting; nice example of a well employed sword, with the point of the balance well down towards the point, ideal for a weapon designed to deal powerful cutting and thrusting blows. See E. Oakeshott,The sword in the Age of the Chivalry, Woodbridge, 1964 (1994); Dufty, A.R.,European swords and daggers at the tower of London,London, 1974; Oakeshott, E.Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991; similar to a specimen preserved in the Tower Armoury (Dufty, 1974, pl.4a); other very similar specimen (maybe the most similar) is the sword in the Royal Armouries (inv. IX.1083), formerly d’Acre Edwards (Oakeshott, 1991, p.149"). Another sword from the River Thames, found in Westminster opposite the Houses of the Parliament (Oakeshott, 1991, p.148) shows the same point with the lower flat blade tapering strongly, and a very stout diamond-section reinforced point. 804 grams, 1.02m (40").From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.This blade form developed as a direct offensive answer to the newly developed, reinforced mail armour of the period 1300-1350 AD. It was broad and flat in section enough, to provide an efficient cutting edge, but the lower part, below the end of the fuller, was nearly always of a stiff-flattened-diamond in section, with a strong median ridge, making it suitable for thrusting as well. The fact that not all the swords of this category have a ridged lower blade, makes sometimes difficult to distinguish the blades of type XVI from the blades of type XIV. These blades are quite often visible in the medieval art, especially in Italian early 14th century AD paintings (Oakeshott, 1991, p.147, lett. Iii and ii"). These are paintings from the Saint Gimignano Cathedral, whose artists copied the swords from real life, like all the artists of the Middle Age: soldiers at the Killing of the Innocents, soldiers at the Road to the Calvary and at the Crucifixion of Our Lord, warriors at the Killing of the sons of Lot. They show as this kind of sword was very popular at the beginning of 14th century in Italy, where maybe the typology was born. They highlight also about the way in which the grips were done: in grey, red or black leather, while the scabbards are mostly black and grey. Such swords are also visible in medieval English art, like in the sword kept from Saint Peter on a roof-boss in the Exeter Cathedral (dated 1328 AD"). The most striking thing about these blades is that they seem very clearly to be made to serve the dual purpose of cutting and thrusting. The upper part of the blade was in the old style, but the lower part was acute enough, and stiff enough to thrust effectively. Thus it may have been equally useful against the armour prevalent in the first half of the 14th century—mail, mixed mail and plate (or 'splinted armour'), or complete plate. Froissart describes two episodes in which the point was so acute to penetrate a plate armour: writing about an incident during the pursuit after the battle of Poitiers (1356 AD) he says: 'When the Lord of Berkeley had followed for some time, John de Hellenes turned about, put his sword under his arm in the manner of a lance, and thus advanced upon his adversary who, taking his sword by the handle, flourished it, and lifted up his arm to strike the squire as he passed. John de Hellenes, seeing the intended stroke, avoided it, but did not miss his own. For as they passed each other, by a blow on the arm he made Lord Berkeley's sword fall to the ground. When the knight found that he had lost his sword, and that the squire retained his own, he dismounted and made for the place where his sword lays. But before he could get there the squire gave him a violent thrust, which passed through both of his thighs so that he fell to the ground.' At the same time there was enough width and edge at the 'centre of percussion' or 'optimal striking point' to enable the blade to strike a very powerful shearing blow. These swords were therefore designed and intended to cut through mail and pierce plate. We may reasonably date the type to the period when all the kinds of armour, previously mentioned, were in use together, so at the beginning of 14th century AD, a period in which, in Italy, together with the early plate armours, great use of the very hard to penetrate protections in cuir bouilli, widely visible on the graves of the Angevine knights in South Italy and in the over mentioned paintings of San Gimignano.Fine condition, restored.

Late 16th century AD. A Western European war hammer (reiterhammer) made of two pieces, the iron shaft and the head; the head made as a single solid iron bar, shaped like a squared hammer from one side and a pointed curved spike from the other side; the head showing a strong quadrangular outline, fixed to the shaft with an upper insertion hole and then rivetted, with the help of an auxiliary iron cap; the spike is a 'raven beak' shape of pointed section, while the hammer is flat at the top; the shaft is circular and ends, in the lower part, with a short handle between two and three circular grooves. See Thordeman, B.,Armour from the Battle of Wisby, Malmö, 1939 (2001); Wilkinson, H., Antique Arms and Armour, London, 1972; Edge D., Miles Paddock J., Arms and Armour of the Medieval Knight, London, 1988; our war hammer is of the type used by European cavalry in the 16th century, represented in the iconography (battle of San Romano, painting by Paolo Uccello of 1455 AD; portrait of Maurice of Saxony made in 1578 AD by Lucas Cranach the Younger) and correspondent with various specimens, such as the one exhibited in the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin. 903 grams, 58cm (22 3/4").From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.This war hammer is of the type used by European cavalry in the 16th century, represented in iconography (battle of San Romano, painting by Paolo Uccello of 1455 AD; portrait of Maurice of Saxony made in 1578 AD by Lucas Cranach the Younger) and showing parallels with similar examples in the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin. Reiterhammers of this type are called ‘raven’s beak’ (bec de courbin) in the sources; the shaft was originally a wooden shank reinforced by metal shafts with one-handed handle, but in the later models, like our specimen, the astile could be entirely in metal, thinner than the wooden one, with guard and knob to better ensure the grip on the handle for a user wearing a glove. The war hammer was developed to counter the protection offered by plate armour, which made simple cutting weapons useless. In a military context dominated by the figure of the knight in plate armour, the sword lost its status as a weapon par excellence. The evolution of this offensive weapon ran in parallel with that of complete armour. When the latter developed ridges to limit the damage from thrusting hits, the war hammer gained prominence as a penetrating weapon. Weapons capable of concentrating a considerable force on a narrow target, a joint or a precise point of the armour proved to be more effective in the fray. As much as the mace of arms and the archer’s axe, the war-hammer became a decisive melee weapon for the knight. The weapon, descended from the East-Roman akouphion, began to be used by armoured knights in the 14th century, due to the need to better the axe and the mace of arms with a piece of equipment capable of inflicting injuries through armour. It reached its full development only at the end of the 15th century, but its wide use in the 16th century is widely documented by archaeological artefacts and iconography, like the one representing the battle of Dreux, in an engraving of 1588 AD, one of the first clashes of the Wars of Religion in France, where knights are visible fighting on horseback with such weapons in their hands. The war hammer was often visible in tournaments, and, much like sword hilts, war hammers became richly decorated with etching and gilding, often appearing to be works of art. However, they never lost their primary function as dangerous weapons (Edge-Miles Paddock, 1988, p.149"). With the seventeenth century and the establishment of portable firearms (pistol and petronel) as weapons of the new heavy cavalry (Cuirassiers and Reiters) the war hammer disappeared from western battlefields. In Eastern Europe, its variants, such as the Polish nazdiak, remained in use among cavalry forces until the 18th century, when it finally fell into disuse along with the axe and mace, starting from the Napoleonic Wars, when the model of the horseman armed only with sabre and pistol became dominant.Fine condition.

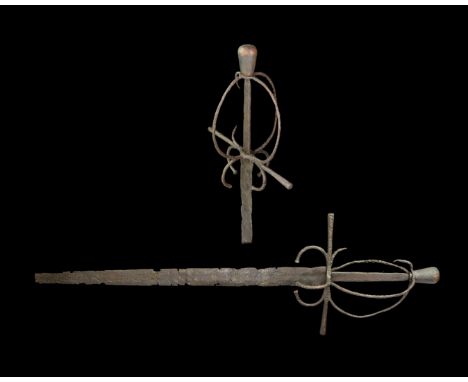

Mid 16th-early 17th century AD. A rapier of possible Spanish or Italian manufacture; the open basket-hilt sword, fitted with the blade, has straight double-edges with a pointed blade(?), presenting a hilt with straight quillons; the side guards are still preserved, together with the arms of the hilt and the knuckle bows; with two additional rings on the lower part of the hilt, bowing towards the flat undecorated blade; the sides of the blades show strong signs of employment in battle. See Tarassuk L., Blair C., The complete Encyclopedia of arms and weapons, Verona, 1986. 1.6 kg, 94cm (37").From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.A variety of swords were used by the Englishmen during the Tudor period, these included the cutting sword, the broadsword and the rapier. The cutting sword was useful in the medieval period but was less effective on the battlefield by the time the Tudor era began. It was consequently replaced by the rapier which was sleeker and was adopted from Spain. It was a slender sharply pointed sword, mostly used for thrusting attacks, as in fencing. It was very thin and sharp, making it look like a thin pole. The rapier was also used by English noblemen to test their skills at fencing which had become a popular sport during the Tudor period. It was common for the noblemen to wear their rapier along with the civilian dress, usually as a part of the clothing. Discussions about the origin of the use of the rapier in England frequently begin by focusing on the very late 16th century. The term rapier was borrowed in 16th century from the French rapière, which was recorded first in 1474AD in the expression épée rapière, which itself derived from the contemporary Spanish espada ropera, the dress sword carried daily by the Spanish noblemen and gentlemen (Tarassuk-Blair, 1986, pp.401 ff."). This weapon was lighter than the arming sword. With the development of the art of fencing in 16th and 17th century the rapier became narrower and lighter, and so suitable for thrusts only. The teaching of rapier was established in England before 1569, and well before that, the school of the famous Italian teacher Rocco Bonetti, who was already established and active in 1576. Accounts from the 1630s set the time when the rapier replaced the sword and buckler as the weapon of choice for civilian combat as being '20. yeare of Queene Elizabeth' or about 1578. But in order for a weapon to become popular there has to have been training beforehand, in which the Masters of Defence of London played the major' part. This sword is an interesting piece belonging to the early period of diffusion of the rapier in England, with all probability from a battlefield, a castle or a military site. The weapon that embodied the duelling spirit was the rapier. The introduction of the rapier into England was one of the most significant single innovation, yet for those unwilling or unable to use such a 'sophisticated' weapon the 'cut and thrust' sword, arming sword or broadsword remained the primary edged weapon, that is after the omnipresent dagger. The new technique of swordplay, introduced in the mid XVI century, gave emphasis to the point of the blade as main instrument of attack. This brought the change of the structure of the sword's guard. In order to point the blade more effectively, some swordsmen used to put one or more fingers in front of the quillons, and these fingers needed to be protected by the arms of the hilt and side guards. Since ordinary gloves were usually worn during an encounter, the increase of all these elements of the guard became a necessity to cover the hand of the target nearest to the opponent. The English at the end of the 16th century followed the continental fencers in taking on the use of the rapier. Just to give a glimpse we can remember as on September 22nd, 1598, two men wandered out into the damp fields of Hoxton, north of London. On that muddy ground, they drew swords – at least one of which was 'a certain sword of iron and steel called a rapier, of the price of three shillings” and fought. At the end of the affray, one man lay dead, suffering 'a mortal wound, to the depth of six inches and the breadth of one inch' to his right side. That man was Gabriel Spencer, a play-actor in the Lord Admiral’s Men and the man that killed him was Ben Jonson, the playwright, friend of William Shakespeare and one of the most famous dramatists of the age. In defence of a proper English technique, George Silver published a treatise called the Paradoxes of the defence, a treatise which was used to espouse the use of the English weapons and to downplay the use of the rapier. Silver hated the Italians and Spanish and made sure that his readers knew that these styles were more dangerous for the user than good English practices. He also wrote a treatise on his Paradoxes called Brief Instructions. The Italian Elizabethan Masters were instead Saviolo and Di Grassi. Saviolo' s works cover not only his view on fencing mechanics but also the concept of the honour. Di Grassi treatise in particular was one of the finer manuals translated to English in this time period. Although Di Grassi predates the Elizabethan period, his manual, which was originally published in 1570, was translated into English in the late Elizabethan period. Not every sword maker could make a good rapier blade. The most part of the blades were made in specialised workshops: in Italy, Milan and Brescia; in Spain, Toledo and Valencia; in Germany, Solingen and Passau. From these cities the blades were exported throughout all Europe, and the hilts mounted in accordance with local fashion and decoration. For example, although Milano, Napoli, and Palermo were subjects of Spain, the decoration style was typically Italian. In Southern Italy the dominant features were the fuller running down the blade and the decorative work using the technique à jour.Fine condition. Rare.

Early 16th century AD. A substantial and important gold signet ring comprising a D-section hoop, facetted shoulders and octagonal bezel; the underside with cable detailing, the shoulders with three swept flutes, each with a band of cinquefoil and foliage ornament; the bezel with intaglio ropework border enclosing an olive branch set horizontally above a heater shield depicting thereon an enigmatic merchant's mark comprising a central cross with crescent ends to top and side limbs, with lateral spur to the foot; the cross flanked to left by the a crescent with six-pointed star below and a larger six-pointed star to right; the six-pointed star appears as a mintmark on the coins of Henry VIII of the York mint for the period 1514-1526 AD and the crescent also at York mint (and Durham) similarly for the period 1526-1529 AD. See Rylands, J. Paul Merchants' marks and other medieval personal marks in Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 1910 (copy of illustrations therefrom included); Boardman, J. & Scarisbrick, D. The Ralph Harari Collection of Finger Rings, London, 1977, item 167 for type; see de Ricci, Seymour, Catalogue of a Collection of Ancient Rings formed by the late E Guilhou, Paris, 1912 (reprinted"). 16.55 grams, 23.00mm overall, 18.03mm internal diameter (approximate size British O 1/2, USA 7 1/4, Europe 15.61, Japan 15) (1"). Found while searching with a metal detector in a private garden near Bridlington Priory, East Riding of Yorkshire, UK, by William Coultas on 15th March 2019; declared as Treasure under the Treasure Act 1996 with Treasure reference number 2019T326, subsequently disclaimed and returned to the finder after the local museum was found not to be in a position to acquire it; accompanied by copies of various documents pertaining to the find from the Treasure Registrar at the British Museum, and a copy of the Report to HM Coroner on the find by Adam Parker, plus a copy of the receipt from the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport; also copies of the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) report [YORYM-5DBF7D], an original copy of The Searcher magazine with an article on it's finding, and a photograph of the ring taken when it was found.PublishedThe Garden of Dreams, by Will Coultas in The Searcher magazine, no.406, June 2019, p.30; and also mentioned on the front cover.Bridlington Priory was an Augustinian priory in the diocese of York, founded in 1113 AD and dissolved during the Reformation (Dissolution of the Monasteries"). The site of the priory is now occupied by a parish church dedicated to St. Mary. Walter de Gant was the founder of what was one of the earliest Augustinian establishments in England, a double-house with a convent, confirmed in charters by King Henry I. An Anglo-Saxon church and nunnery had occupied the site before the Norman invasion. The first prior may have been called 'Guicheman', a Norman corruption of the English name 'Wickeman'. The priory enjoyed royal favour and owned lands across Yorkshire. Its Canons established a separate foundation, Newburgh Priory, in 1145 AD and King Stephen granted it the right to confiscate the property of felons and fugitives within the town, alongside dues from the harbour. In 1200 AD, John granted leave to hold a yearly fair in the town. During the Anarchy, the Canons were expelled and the buildings fortified by William le Gros, who later awarded it six manors, one at Boynton and the rest in Holderness. Henry IV awarded the priory the rectory of Scarborough. A royal licence to crenelate was granted by Richard II in 1388 AD but it seems that only the Baylegate of the four known entrances was fortified. The priory also had an extensive library, documented by John Leland, the 16th century antiquary and poet, shortly before its Dissolution in 1538 AD. The priory was a very wealthy institution with extensive landholdings across northern England. The church itself was an impressive building some 390 ft (about 120 m) in length with carved interior woodwork by William Brownflete. The fabric of the priory was largely destroyed, with the nave remaining to form the frame of the existing parish church. Medieval and Tudor merchant's marks such as this example were a non statutory system for identifying personal property or to confirm identity, separate from the hereditary heraldry used by noble families. These marks were used on seals attached to goods for identification purposes or for sealing documents, and the designs were sometimes displayed on a heater shield (as on the present ring) in a more formal context. The cinquefoils are identified by Adam Parker, Finds Liaison Officer for N&E Yorkshire as carnations, also known as 'pinks' and signifying 'betrothal'. A similar merchant's mark appears on the reverse of a ring in the de Guilhou collection, which also features a comparable cable design to the hoop, for which a 16th century date is suggested in Boardman and Scarisbrick. This ring is of very good quality with exceptional workmanship evident to all of its features; it would undoubtedly have been the property of a wealthy and important merchant; merchant marks are enigmatic and secretive by their nature and often hold punning references to personal names so, for example, the presence of an olive branch could suggest the name Oliver. Some studies of such marks have been undertaken since the 19th century in a few localities and archives but, to date, there seems to have been no attempt to carry out a systemic national study of this fascinating subject nor to compile a corpus of examples from museum collections and public records. Very fine condition; traces of niello fill to the cinquefoils. Very rare.

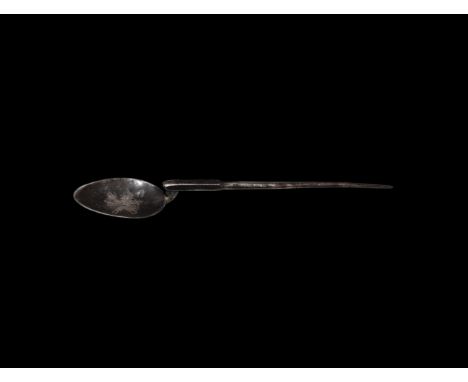

6th century AD. A silver spoon used for the Holy Eucharist, with a long stem, stamped inside with the Christian monogram, in the center of the bowl; this christogram was formed from the first two letters of 'Christ' in Greek (chi = X and rho = P) and used extensively in the Roman Christian Empire. Cf. Beutler F., Farka C, Gugl C., Humer F., Kremer G., Polhammer E. (ed.), Der Adler Roms, Carnuntum und die Armee der Casaren, Bad Voslau, 2017, p.186, n.74. 33 grams, 19cm (7 1/2"). From a home counties collection, formed 1970-1980. Very fine condition.

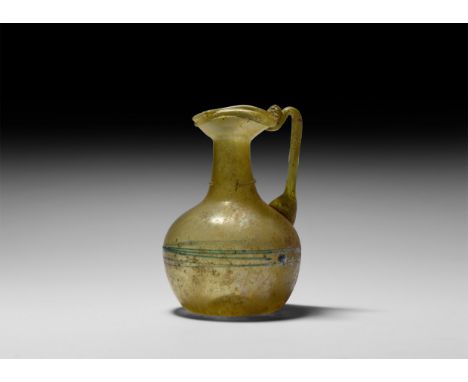

1st-2nd century AD. A small green glass collared globular jug with short neck, angular ribbon handle with two narrow prominent ribs, folded upper attachment to the cylindrical neck, blue-green lines on the globular body, trefoil mouth. See Cool H. and Price J., Colchester Archaeological Reports, Report 8: Roman vessel glass from excavations in Colchester, 1971-85, Colchester, 1995, fig.888, p.125, 915. 66.5 grams, 11cm (4 1/4"). From an important Mayfair collection formed from 1970-1990s. Globular and conical jugs of Isings forms are found dating to between the first and the second century AD in the Roman provinces, like Britannia. The translucent glass may be divided into four broad categories; strongly-coloured, lightly-tinted, colourless, and blue/green glass, like this specimen. Blue/green glass was used to make vessels throughout the first three centuries, but became much less common in the 4th century, when the commonest vessel types were most frequently made in a range of pale green or yellow shades. Fine condition.

2nd-3rd century AD. Two sheet silver embossed plaques for a pseudo-Attic helmet, each with shaped edges, embossed around the edges with a double-pearled ornament, with fixing holes; the decoration of both plaques seems to represent a cult scene, most probably to Jupiter and Epona, in one plaque, to Jupiter alone; the bust of Jupiter is represented on both plaques at the centre of the diadem, frontally, with long, symmetrical hairstyle; he is dressed in a simple folded tunic; an eagle at his right side, his favoured bird and symbol of his power over the skies, as well as of the eternal power of Rome; the feet of both eagles rest on thunderbolts, composed from a turtled elongated body; to the first plaque, another divinity is represented to the left of Jupiter, most probably Epona, left hand holding a staff surmounted by flowers, fruit and ears of corn (cornucopia?); on the left side of the plaque, under the divinities, are two advancing cavalrymen, one dressed with a padded tunic of Celto-Danubian typology, holding a short sword, the other unarmed and lightly dressed; opposite, the god Silvanus seated and covered only by his mantle, is offering the victory laurel to an eagle resting over a basket, caressing a dog; and three female figures (one half naked and with the breast exposed, the other two dressed with chiton and chlamys) are performing an offering in front of a templar construction, one figure holding a staff and the other a standard ending with a seven-pointed star; at the feet of the woman with the staff another dog is lying, probably again associated with the offering god; to the second plaque: the embossed decoration consists mainly of an armed cavalryman, identical to that one on the previous plaques, advancing towards Zeus/Jupiter; two different cult scenes are represented on the sides, on the left a divinity (maybe Silvanus), leaned upon a staff, is offering gifts to a divinity (Epona?), represented as a bust; on the right side a similar figure offering gifts to a cavalryman, preserved only in his lower part; under the central figures are again represented, in smaller dimensions, two divinities, Zeus/Jupiter and Athena/Minerva, the one holding a staff, the second one helmetted and carrying a spear with her right hand, the other hand on a shield; the two figures are flanked by a naked horseman, while the heads of the twins Castor and Pollux are positioned on both their flanks; both plaques with holes for the fastening through small rivets on their sides (still present in the smaller plaques, only one preserved in the bigger plaque), intended to affix the plaques to the crown of the helmet; mounted on perspex.See Fray Bober P., Reviewing Réne Magnen, Epona, Déesse Gauloise des Chevaux, Protectrice des Cavaliers, in American Journal of Archaeology, 62.3, July 1958, pp.349-350; Robinson, R., The Armour of Imperial Rome, New York, 1975; D'Amato, R., Arms and Armour of the Imperial Roman Soldier, London, 2009; Negin A. Roman helmets with a browband shaped as a vertical fronton, in Historia i ?wiat, 2015, 4, 31-46; D'Amato R., A. Negin, Decorated Roman Armour, London, 2017; the helmet browband embossing has parallels with other splendid vertical fronton-shaped specimens, like the helmet from PamukMogila, the fragment of helmet from Leidscherijn, the browband from Leiden, and the very famous helmet recently found in Hallaton (D'Amato-Negin, 2017, fig.62 c, p.64-66); the piece preserved in the National Museum of Antiquities (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden) in Leiden (D'Amato-Negin, 2017, fig.65) shows similar embossing and side holes for fastening. These embossed plaques would have been affixed to the browbands, of the ‘pseudo-Attic’ helmets of the Roman army. The existence of these helmets, the most represented in Roman art (Robinson, 1975, p.182, pl.494; pp.184-185, pls.497-499, 501) although less documented in archaeology, have been a matter of controversy amongst scholars. 1.02 kg total, 30-35cm long (11 3/4 - 13 3/4").Ex an important Dutch collection; acquired in the European market in the 1970s; accompanied by an expertise by military archaeologist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.Despite a number of experts doubting their existence, Russell Robinson published the brow-band of a surviving example over forty years ago (1975, pp.138-139, pls.417-220"). Some scholars are absolutely confident of their existence (D'Amato, 2009, pp.112-114; 206ff.), while others considered the many images of Attic helmets on Roman monuments simply an artistic convention. Recently, Andrei Neginhas collected a good series of samples showing that the presence of these helmets was a reality of the Roman Army (Negin, 2015), a thesis further reinforced in D'Amato and Negin’s 2017 work on Roman decorated armour. Both the authors have shown full evidence with finds suggesting that Attic helmets with browbands, which are often depicted in Roman public art, are no mere convention, but were actually common in the Roman imperial army, imitating models from the earlier period. In the case of similar helmets worn by the Praetorians, it can be assumed that they had more archaic shapes, imitating Greek models. They are exceptionally rare pieces, coming with all probability from a military camp on the Danube. The scene represented here shows a cult to divinities popular among the legions of the Danube; the presence of cavalrymen recalls the cult of the Danubian rider gods, here dressed like a Thracian auxiliary cavalryman of the Roman army, and joined by the rider gods par excellence, the twins Castor and Pollux. The presence of Epona, protector of horses, goddess of fertility, confirms the helmet’s Danubian origin, Epona being 'the sole Celtic divinity ultimately worshipped in Rome itself' (Fray Bober, 1958, p.349"). Her worship as the patroness of cavalry was widespread in the Empire between the first and third centuries AD; this is unusual for a Celtic deity, most of whom were associated with specific localities. Here, she is associated with Silvanus, a god also venerated in the Danubian provinces, a divinity especially popular in Pannonia, and in the cities of Carnuntum and Aquincumwhere he was worshipped as Silvanus Orientalis, the divine guard of the borders.[2] Fragmentary.

2nd millennium BC. A matched pair of silver pendants, each formed as two coiled ends of a rod with heart-shaped loop between forming a volute scroll. Cf. Aruz, J. Art of the First Cities. The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, New York, 2003, item 246. 107 grams total, 93mm each (3 3/4"). From a private collection, Lancashire, UK; acquired on the UK art market; previously in an early 1990s London collection. [2] Fine condition.

Early 13th century AD. An iron longsword of Oakeshott's Type XIIIA, cross style 1, pommel type H; a 'Bastard' sword (sword that can also be used with two hands), with long tapering blade, cutting edges running nearly parallel to the tip; just below the hilt, before the edges begin their virtual straight running to the point, the blade is swelling slightly in width; the narrow fullers extended for two-thirds of its length; the lower guard is simple and straight; the grip is longer than usual of type XIII allowing for the off-hand to be used for extra leverage and power; the pommel is highly decorated with two different inlays, from one side a circular space divided in eight sections, the other side with a possible heraldic symbol, representing a triangular shield decorated with embossed annulets surmounting a kantharos from which water is springing; both images are inscribed inside a golden circle; some corrosions on the lower edges but no evidence of traces of fighting nicks, both cutting edges are well preserved; German or English manufacture. See Petersen, J., De Norske Vikingsverd, Oslo, 1919; Shetelig, H., Scandinavian Archaeology, Oxford, 1937; Oakeshott, E.,The archaeology of the weapons, arms and armours from Prehistory to the age of Chivalry, Woodbridge, 1960 (1999); Oakeshott, E., The sword in the Age of the Chivalry, Woodbridge, 1964 (1994); Oakeshott, E., Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991; the sword, belongs to the type of 'war sword' and finds a good correspondence with various swords of the first half of the 14th century, like some specimens preserved in the Museum Art Gallery of Glasgow (Oakeshott, 1991, pp.103 n.7; 105, nn.10-11); for what concern the cross-guard, it is of a simple and obvious form, a straight bar tapering slightly toward the ends; first found in Viking graves of the 10th century (s. Shetelig, 1937), and called by the Vikings Gaddhjalt (Spike-Hilt, s. Petersen, 1919), it was still in use in the Renaissance (Oakeshott, 1994, p.113 and plates IC, 6A and 46B), generally square in section, it may sometimes be circular, or in rare, late cases octagonal; pommel forms vary very often on the survival specimens, though the wheel shape from H to K predominate; crosses both on surviving example and those shown in the art are nearly always straight, generally of type 1 or 2; there are some excellent pictures of these swords in an English manuscript of the early years of the fourteenth century (B.M. MS. Roy. 19.B.XV, an Apocalypse of St. John (Oakeshott, 1994, fig.89-90); nearly every German military tomb effigy of the period between about 1280-1350 AD has one of these big swords and several are shown on English effigies, as for instance at Astbury in Cheshire; one very good example on an English tomb is difficult to see—a little mounted figure high up on the canopy of Edmund Crouchback's tomb in Westminster Abbey; Edmund was the Earl of Lancaster, second son of Henry III, and died in 1296. It is possible to see it if you climb up into the Islip Chapel in the North Choir aisle, for this is raised about 30 ft. above the level of the floor; look across the aisle over the parapet of the chapel which spans the arch containing it and there is this small knight with a great war sword girt to his waist (Oakeshott,1994, fig.92); another of an earlier date is to be found in an admirable little drawing of a knight fighting a giant upon a page of a small Psalter made for the eldest son of Edward I of England, Alphonso, who died in 1284 (Oakeshott, 1994, fig.91"). 1.3 kg, 1.03m (40 1/2").From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.A long double-handed sword, Oakeshott type XIIIa; the most beautiful element of this sword is its decorative pommel, of type H in the Oakeshott classification (Oakeshott, 1994, p.95"). This is one of the commonest of all medieval pommels, where the edges of the disc are chamfered off on each face, giving a low prominence on either side, the inner, flat faces being about a quarter less in diameter than the outer rim. It is found on swords of every type from the 10th century until the early 15th century AD, and after three-quarters of a century of apparent unpopularity it appears again, rarely, between c.1500-1525. What is extraordinary is not the pommel in itself, but the inlaid decoration over it. The shield with annulets ('little rings' in heraldry) visible on one side is a common charge, which may allude to the custom of the prelates to receive their investiture per baculum et annulum i.e. 'by rod and by ring', and can also be described as a roundel that has been 'voided' (ie. with its centre cut out"). In medieval English heraldry, annulets could represent a fifth son. The shield is surmounted by a pot from which water is springing, an obvious connection with the biblical passage: 'Jesus answered: Everyone who drinks this water will be thirsty again, but whoever drinks the water I give them will never thirst. Indeed, the water I give them will become in them a spring of water welling up to eternal life'' (John, IV,13-14"). The solar disc on the other side of the pommel evokes Christ's ancient monogram. These references to Christian symbolism suggest that the owner of the sword was an clergyman, maybe the fifth son of an aristocratic English family.Fine condition. Very rare.

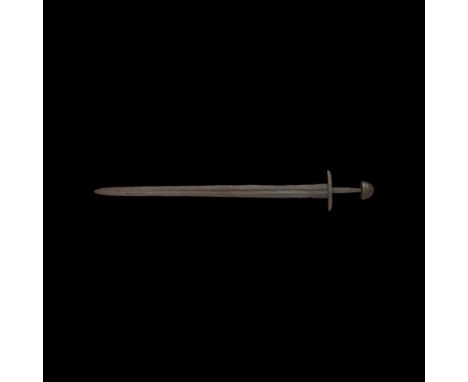

Mid 10th-mid 11th century AD. A western European long double cutting sword with broad tapering blade with evidence of its use on the battlefield; wide shallow fullers occupy half of the blade's width, inlaid with a simple Greek cross and X within a circle; a long straight guard and a broad short grip, the stout tang ending with the usual plain Brazil nut pommel. See Oakeshott, J. R. E., The Archaeology of the weapons, London, 1960; Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002; Nicolle, D., Arms and Armour of the Crusading Era, 1050-1350, vol I, London, 1999; the sword finds a good parallel with a specimen from Spain, published by Peirce (2002, p.124), with another specimen in Cambridge; a 12th century sword from Germany, in the Wallace collection, London, England (Nicolle, 1999, fig.424); also a sword in Dresden, with the name 'INGELRII' on one side and the phrase 'HOMO DEI' on the other, dated circa 1100 AD; and a sword once in the Oakeshott collection with the mark of Carrocium, dated circa 11th century. 799 grams, 91.5cm (36").From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; believed from Lyon, France; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.According to Oakeshott (1960, p.204) the sword of type X, were a development of Viking sword of type VIII with slight modifications. Oakeshott describes such swords as common in the late Viking age (last tenth century) and remaining in use until the first quarter of the 13th century. The evidence in sculptures, shows the pommel being well used into the 12th century, and even until the 1200, as shown by the images of Saint Zeno in Verona, in the scene of Roland and Faragut (Nicolle, 1999, fig.576 A-D").Fine condition, blade tip repaired. Rare.

10th-11th century AD. A fine double-edged sword with tapered pattern-welded blade, still retaining well-defined cutting edges and fullers, although the latter being extremely shallow with vague boundaries; traces of employment in fight are visible with battle nicks on the sides and near the point; the hilt comprises a flat tapering tang and a thicker and shorter pommel of 'tea-cosy' form (type B), decorated with an inlaid circumferential band around its lower edge; the lower guard is reaching a medium length; traces of rusting to the hilt and along the blade. See Petersen, J.,De Norske Vikingsverd, Oslo, 1919; Oakeshott, E. Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991; Roesdahl, E., Wilson D.M., From Viking to Crusader: The Scandinavians and Europe 800 to 1200 (22nd Council of Europe Exhibition), Copenhagen, 1992; Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002; the sword belongs to the well known type X of Petersen (Petersen, 1919, pp.158ff) and Oakeshott type XI (1991, pp.53 ff.), with good parallels in various similar Viking and Norman age specimens (Peirce, 2002, pp.115 ff.); another of the most evident parallels is the sword from Tissø, Denmark, today in the National Museum in Copenhagen, also a water find; other two excellent specimens of this typology may be seen at the Musée de L'Armée, Paris (Peirce, 2002, pp. 118-121); the overall proportions of our specimen are positively eye-catching and it is strikingly similar to a pattern-welded sword found, with a large number of other objects, at Camp de Péran, Côtes-d'Armor, France, in a 10th century context, probably linked with the early Norman settlers in Normandy or Norman raids in Breton Lands (Roesdhal, Wilson,1992 p.321, cat. no.359"). It is in fact probable, that there was a connection between the severe damage caused by fire at the castle of Camp de Peran (near Saint-Brieuc) and the presence of the Vikings in Brittany in the first half of the 10th century; the dates are compatible, considering that in 911 AD, Rollo created the Duchy of Normandy with the Frankish Kingdom investiture; so far there is no evidence as to whether the Vikings were the attackers or had taken up a defensive position there; in this latter case the destruction of the fortifications may have occurred when Alain Barbetorte attacked the site in 936 AD; a large quantity of objects was found during excavations in the 1980s, including a sword similar to our specimen, pattern-welded, with missing point, 75cm long; two spearheads, in iron, an iron axe, an iron stirrup, an iron pot made in the same way as a pot from the Viking grave on the Ile de Groix (Roesdhal, Wilson, 1992, p.321, cat. no.360), and other small items. 974 grams, 93cm (36 1/2").From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; believed from the Danube river; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.The present example is distinguished by having a slender blade, generally long in proportion to the hilt, with a more or less narrow fuller running to within few inches of the point. In classic examples there is a very little taper to the edge, though in well-preserved examples the point is quite acute. However, since so many samples from rivers or ground show so much corrosion at the point, in many surviving examples the point appears to be spatulate and rounded. As in all the other types of swords, the form of the pommel and the cross guard varies considerably. For instance, the early Viking swords of this category had a shorter cross-guard, destined to be elongated in later ages. Originally Oakeshott was limiting the use of such swords in the period between 1100-1175 AD, but now we can consider, all variants included, a 10th-12th century AD date range of full use of such swords. The B type pommel is indicative of the category. There is a depiction of William the Conqueror in the Bayeux Tapestry with a 'tea cosy' pommel sword.Fine condition. Rare.

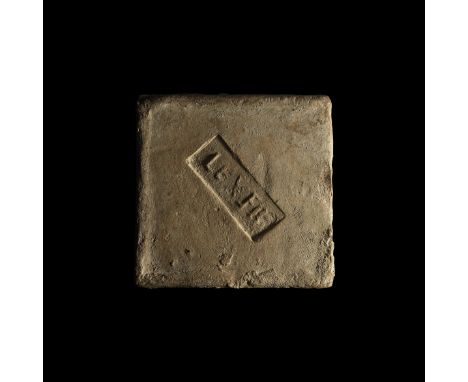

1st century BC-1st century AD. A square ceramic floor tile (tegula) with rectangular impression to the upper face 'LEXFR' for Legio X Fretensis (Tenth legion of the Strait"). See Hillel, G., The Camp of the Tenth Legion in Jerusalem: An Archaeological Reconsideration in Israel Exploration Journal Vol. 34, No. 4 (1984), pp. 239-254. 1.8 kg, 18.5 cm (7 1/4"). From an important central London collection formed since the mid 1960s; thence by descent. The Tenth Legion was raised by Gaius Octavius (later called Augustus Caesar) in 41/40 BC and fought against Sextus Pompey in the Battle of Naulochus, where its cognomen Fretensis was awarded, in reference to the fact that the battle took place near the Strait of Messina (Fretum Siculum"). The legion went on to serve in the First Jewish-Roman War (66–73), under Vespasian and the suppression of the uprising in Jerusalem. Under the command of Titus this was the Legion who besieged and destroyed Jerusalem and the Holy Temple. The tile was found in present day Jerusalem. The 10th Legion was still a fighting forcer at the end of the 4th century when the Notitia Dignitatum was compiled. Fine condition.

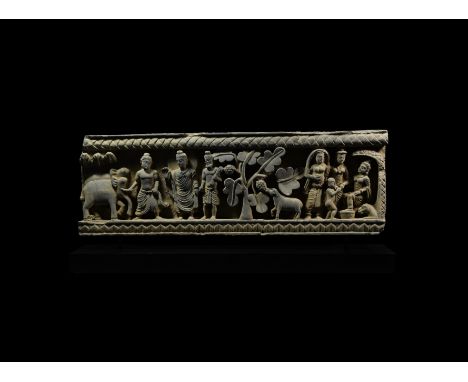

2nd-3rd century AD. The Buddha's experiences in the rural landscape are evinced in this carved schist frieze in which the teacher appears, facing a nimbate figure wearing a loosely draped robe hanging from his frame and with the long unwound end raised and looped around his right wrist; beside him a mahoot leads a team of two elephants, similarly simply dressed, while to his right a stocky bearded figures carries a sheaf on his left arm; a goat nibbles at the bark of a tree separating the first scene from the second in which three voluptuous females dote on the boyish nude Buddha; bands of undulating ornament above and below frame the imagery; mounted on a custom-made stand. Cf. Jongeward, D. Buddhist Art of Gandhara in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 2018, item 52 for similar decorative framing to a frieze. Exhibited at ‘The Buddha Image: Out of Uddiyana’, Tibet House, 22 West 15th Street, New York, 16 September-20 October 2010, extended to 16 November and again to 7 January 2011; accompanied by a copy of the main Tibet House exhibition press release. 35.7 kg, 88cm wide including stand (34 1/2"). Acquired for the ‘Buckingham Collection’ by the late Nik Douglas (1944-2012), renowned author, curator and Asian art expert; the collection formed from the early 1960s to early 1970s; displayed at the major exhibition ‘The Buddha Image: Out of Uddiyana’, Tibet House, 22 West 15th Street, New York, 16 September-20 October 2010, extended to 16 November and again to 7 January 2011; where the collection of one hundred pieces was publicly valued at US$ 15M; this piece was scheduled to be included in an exhibition entitled ‘On the Silk Route; Birth of The Buddha’, to be held in London from November 2012, but sadly his death prevented this; accompanied by copies of several press releases and articles for the exhibition, including Artnet News, This Week in New York, Huffpost and Buddhist Art News. Fine condition.

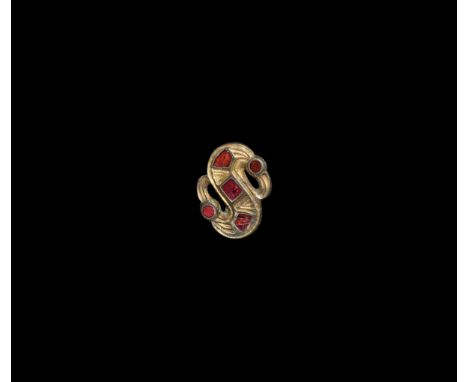

5th-6th century AD. A silver-gilt bird brooch with chip-carved bands, inset hatched foil backed garnet cloisons to the eyes and body, catch and sprung pin to the reverse. Cf. Beck, H. et al. Fibel und Fibeltracht, Berlin, 2000, item 468; similar brooches from the Frankish cemetery at Monceau-le-Neuf-et-Faucouzy, deptn Aisne, France in Menghin, W. The Merovingian Period. Europe Without Borders, item VII.23.2; and the S-fibula from Schwarz-Rheindorf, Westphalia, in Menghin, W. The Merovingian Period. Europe Without Borders, item VII.48.27. 6.3 grams, 28mm (1"). From an important private family collection; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent. During the mid-sixth century the S-brooch, along with the disc brooch, became popular. These were made primarily of gilded silver embellished with garnet inlays or in garnet cloisonné. Early forms of S-shaped brooches appear in graves in Scandinavia throughout the fifth century and in Europe during the first decades of the sixth century, and reached the height of their popularity during the latter half of that time. They have a wide spread across Europe and are found in central and western Europe, Italy, Scandinavia and Anglo-Saxon England. They generally take the form of an S-shaped body with heads at either end facing in opposite directions. The heads are generally depicted as birds but examples are known of unidentified animals with splayed open jaws, possibly dragons or wolves. The use of the head imagery is consistent with the aesthetic tendencies associated with the northern, Pagan Germanic world. Very fine condition.

Mid 16th century AD. A German Renaissance 'hand and a half' or 'Bastard' sword, with ring guard, double-edged broad blade, lenticular in section, with single short shallow fuller, running up half of its length; complex hilt, with pommel (style T1) in shape of truncated wedge, closed by a rivet on the top, long tang, cross-guard widening towards the edges where the iron quillons are ending with a triangle; the handle presents a double-sided guard together with the knuckle bow; it shows two additional rings on the lower part of the hilt, bowing towards the flat blade, which is decorated with an unidentified maker’s mark, impressed just under the fuller. See Talhoffers Fechtbuch aus dem Jahre 1467, gerichtliche und andere zwei Kämpfe darstellend, ed. Hergsell G., Prag,1887; Dufty, A.R., European Swords and daggers in the Tower of London, London, 1974; Talhoffer, H., Medieval Combat: a Fifteenth-Century Illustrated Manual of Swordfighting and Close-Quarter Combat, by Rector, M. (ed.), London, 2000; Oakeshott, E.,Sword in hand, London, 2001; the sword is a good parallel with the sword kept in the Tower, published by Dufty (1974, pl.14, lett.a), clearly coming from the same workshop, as shown by the same mark impressed upon the blade (1974, pl.106, lett.9b"). 1.4 kg, 1.2m (47 1/4").From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; believed from Leige, Belgium; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.In the inventory of the Tower of London, in 1547 AD, Grete slaghe swordesie. two handers, are mentioned. Since the last quarter of the 15th century began the development of the hilt of the arming sword, which eventually become a rapier, paralleled by the big 'bastard' swords (Oakeshott, 2001, p.137"). Until 1500 AD, the two-handed sword was mainly relegated to use in duels, so much so that in 1409 AD Fiore dei Liberi published the first Italian manual on the use of this weapon, followed by Filippo Vadi some ten years later, who drafted also a series of points necessary to allow a sword to be defined as 'two-handed'. In the famous Talhoffers Fechtbuch are illustrated the various ways and movements of such combats with the double-handed sword: the first sixty seven plates are dedicated to the fight with the 'Langes Schwert' (longsword"). The fencing is analysed in all the various moments, by instructing regarding positions or guards until the guidance of real blows: at the beginning, further explaining the various engagements, as well as how the most varied movements with the blade and the handles should be done, and mentioning the various booklets about the sword. The fencing is analysed in detail. The author explains how to put focus on the key moments of the fight: how to hold the point of the blade and to rip with the quillons of the handle, how to make a blow with reversed sword or how to push with the sword pommel against the face of the opponent, or to complete the fight in appropriate moments by a wrestling match. Finally, without having incurred any damage, the author explains how to emerge victorious or disarm the opponent. With the arrival of the new century, the grip was made safer by altering at the handle and the base of the blade, which was lengthened until the sword reached the height of a man; moreover, the two-handed sword gained popularity in battle, where it was used to knock down the wall of enemy spades. The average weight of a two-handed sword was about one and a half kilograms, and the total length ranged from 110 to 150 cm. The 16th century was the peak of their popularity as weapons, Jacopo Gelli in his Guida del raccoglitore e dell’amatore di armiantiche (Guide for the collector and enthusiast of ancient weapons) defines such a weapon as 'Big Swiss Longsword', shaped like a biscia (whirlpool), used during the XVI century, to not be confused with the hand and half sword, having a snaked blade (from the French Flamboyante"). Italian sword makers referred always to such kind of blade as 'a biscia', imitating the shape of a creeping snake on the ground.Fine condition. Rare.

2nd-1st century BC. A bronze fitting comprising a lobed base with attachment loop below, standing figure of a centaur with curved club resting on the shoulder, left foreleg raised and supported on a spigot, curved triangular-section arch connected to the rump terminating in a crescent over the figure's head; mounted on a custom-made stand, possibly a chariot fitting. See Langdon, S. Art and Identity in Dark Age Greece, 1100-700 BCE, Cambridge University Press, 2008; statuettes of centaur are visible in the Greek Art since the 8th century BC (Metropolitan Museum inventory number 17.190.2072) and continued in the Archaic (statuette of a centaur in Princeton Museum, 530 BC) and Hellenistic world. 414 grams total, 22.5cm with stand (9").Property of a London gentleman; previously acquired on the UK art market in the 1990s.The first attested image of a centaur dates from the 10th century, from Lefkandi, possibly representing Chiron, who trained the heroes Heracles and Achilles. By the 8th century BC, centaurs, typically represented on pottery, were shown in wild areas, existing between civilisation and the natural world. There is no known representation of a centaur engaged in combat or violence. Susan Langdon argues that these Attic centaurs show 'positive masculine traits', as they were creatures which trained young boys to be men (Langdon 2008, p.106").Fine condition.

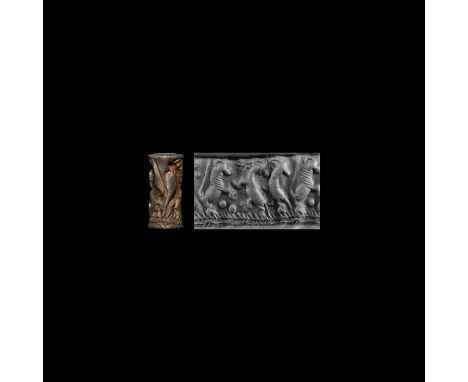

Mid 28th-27th century BC. A silver cylinder seal with a rampant lion with long tail stretched parallel to the back hatched horizontally, hatched mane facing right; attacking two caprids, jumping up and turning their heads backwards to flight; between the lion and the first caprid, above a grid pattern, below two balls, the head of an animal or bird(?); two lines with herringbone pattern appear as a stand line; accompanied by a museum-quality impression. 2.2 grams, 13mm (1/2"). From a private Netherlands collection; previously in an old collection since before 1980. Very fine condition.

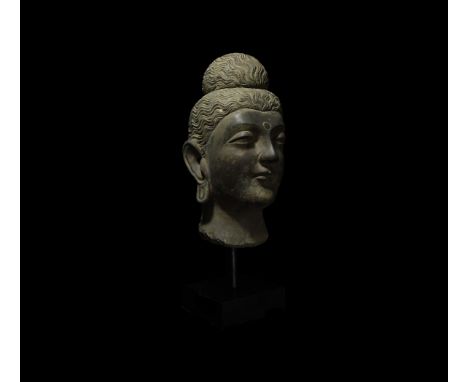

2nd-3rd century AD. Of imposing size and presence while retaining Buddha's serenity, this carved larger than life-size schist head shows Gandharan sculpture's Graeco-Roman legacy; the naturalistic carving of the facial features from ridged eyebrows to rounded chin; the locks of hair flow in sinuous symmetrical waves from the widow's peak to the dome of his ushnisha; the ears are shown long with looped earrings drawing the lobes down towards the neck; the urna sits in low relief above the nasal ridge; mounted on a custom-made stand. Cf. Jongeward, D. Buddhist Art of Gandhara in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 2018, item 70. Exhibited at ‘The Buddha Image: Out of Uddiyana’, Tibet House, 22 West 15th Street, New York, 16 September-20 October 2010, extended to 16 November and again to 7 January 2011; accompanied by a copy of the main Tibet House exhibition press release which shows an image of several of the most important items in the exhibition, including this piece which is first on the left. 32.3 kg, 60cm including stand (23 1/2"). Acquired for the ‘Buckingham Collection’ by the late Nik Douglas (1944-2012), renowned author, curator and Asian art expert; the collection formed from the early 1960s to early 1970s; displayed at the major exhibition ‘The Buddha Image: Out of Uddiyana’, Tibet House, 22 West 15th Street, New York, 16 September-20 October 2010, extended to 16 November and again to 7 January 2011; where the collection of one hundred pieces was publicly valued at US$ 15M; this piece was scheduled to be included in an exhibition entitled ‘On the Silk Route; Birth of The Buddha’, to be held in London from November 2012, but sadly his death prevented this; accompanied by copies of several press releases and articles for the exhibition, including Artnet News, This Week in New York, Huffpost and Buddhist Art News. Accompanied by geologic report No. TL005265 by geologic consultant Dr R. L. Bonewitz. Dr Bonewitz notes: 'No definite source localities have been identified for the stones used by the Gandharan sculptors, but the predominant rock was an alumina-rich chloritoid-paragonite-muscovite-quartz schist, probably from Swat.' Very fine condition, chipped.

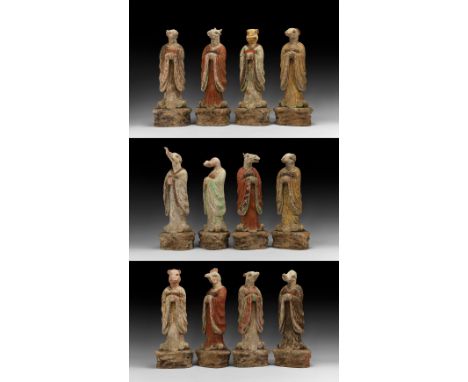

Tang Dynasty, 618-906 AD. An important set of twelve painted shengxiao ceramic zodiac figures, each a cloaked human body standing on a tiered pedestal base with the head of an animal from the Chinese zodiac - pig, ox, horse, ram, rooster, rat, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, monkey and dog; representing the Chinese twelve-year cycle in which each year is associated with a specific animal. See Michaelson, C., Gilded Dragons. Buried Treasures from China's Golden Ages, British Museum Press, 1999, pp.102-103. 37 kg total, 44cm (17 1/2"). Property of a North London gentleman; formerly in the Cheuk family collection, Hong Kong, 1970s; accompanied by Oxford Authentication thermoluminescence report for one of the pieces, number C119j15. The earliest known pictorial representation of the twelve-year cycle is in a Northern Wei tomb in Shandong Province; by the time of the Tang Dynasty the calendrical animals were frequently used on epitaphs and engraved on funerary steles. The Chinese term shengxiao means both birth and resemblance, as it came to be believed that a person's character was influenced by the animal symbolising their year of birth. The belief developed into believing that it was possible to gain insights into relationships and the universe and therefore into one's fate. Each of the animals also represent a specific hour, day, month of the cycle, and all these details are taken into consideration when investigating the almanac for divination purposes. There are a number of stories about the origin of the order in which the animals are placed. The most popular ones include those relating to how the Jade Emperor asked to see earth's twelve most interesting animals on the first day of the first lunar month, in which the rat gained the first position by deception, becoming the sworn enemy of the cat. [12] Finely modelled.

10th-13th century AD. A carved grey sandstone statue of a female deity, probably Lakshmi, wearing a long pleated sampot with frontal fold and belt; the face with benign expression, smiling with full lips; the eyes fully defined and slight ridge to the brow, elongated ears with vertical slits; dressed hair and scooped diadem tied at the rear, piled column above; mounted on a custom-made stand. 115 kg total, 1.45m with stand (57"). Property of an East Sussex gentleman; from his private collection formed between 1983 and 1990; formerly in a South East London collection formed in the 1970s; accompanied by geologic report No. TL005260 by geologic consultant Dr R. L. Bonewitz. Lakshmi is an ancient Indian goddess of prosperity and luck first mentioned in the ?r? S?kta of the Rigveda. She was incorporated in the Vaishnava pantheon as the consort of Vishnu in the 3rd-4th century CE, to become the Hindu goddess of wealth, good fortune, prosperity and beauty. Fine condition.

1st-2nd century AD. A small bronze swing handled situla with lathe turned designs on the body, arched handle with nicely shaped lugs, bronze loops to the sides; possibly used for medical purposes. See a similar item in the Varna Archaeological Museum, preserved inside the grave of a physician, dated to the first or second century AD. 302 grams, 14.5cm (5 3/4"). Property of a South London collector; previously acquired on the European art market 1970-1980. Roman situlae, used for medical, religious or alimentary purposes, favoured a simple shape curving from the base, becoming vertical at the top, with a wide mouth and no shoulder, but sometimes a projecting rim. These included another variety of uses, including for washing and bathing. Any decoration was often concentrated on the upper part of the sides, and often, in the simpler situlae, a lathe decoration as with this specimen. Very fine condition.

2nd millennium BC. A bronze figurine of a nude male standing with hands folded to the midriff, the face with exaggerated nose and eyes, crescent mouth and triangular beard. Cf. Aruz, J. Art of the First Cities. The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, New York, 2003, item 39 for similar stance. 157 grams, 94cm (3 1/4"). From a private collection, Lancashire, UK; acquired on the UK art market; previously in an early 1990s London collection. The use of figurines in a similar stance, standing straight with the hands folded together on the chest, is usually associated with acts of prayer and worship. Aruz (2003) offers many examples of the type in ceramic, bronze and limestone. Some apparently formed part of the foundation deposit for impressive and important buildings; when re-building was necessary, the original figures were re-buried with subsequent re-dedication figures offering a visual summary of the site's construction history. Fine condition.

11th-14th century AD. A carved and polished sandstone statue of the four-armed Vishnu standing, wearing a simple pleated sampot fastened by a band knotted below the waist; the body slender and youthful, the face serene with broad nose and full lips, lengthened earlobes with vertical slits; columnar jatamukata headdress (formed from matted and twisted locks of hair); mounted on a custom-made stand. Cf. Van Beek, Steve and Tettoni, Luca Invernizzi, The Arts of Thailand, 1986, pp.57 and 60 for similar examples. 64.2 kg total, 1.2m with stand (47 1/4"). Property of an East Sussex gentleman; from his private collection formed between 1983 and 1990; formerly in a South East London collection formed in the 1970s; accompanied by geologic report No. TL005269 by geologic consultant Dr R. L. Bonewitz. From the early part of the first millennium AD the South East Asia region was heavily influenced by art, religion, philosophy and literature brought from India by merchants and traders, many of whom settled in the trading posts they set up; the effects of this influx can be seen to the present day and religious art in particular has followed closely the traditions of India. Fine condition.