19th century BC. A carved limestone cylinder seal with three figures and cuneiform text; accompanied by a museum-quality impression and an old scholarly note, typed and signed by W.G. Lambert, late Professor of Assyriology, University of Birmingham, 1970-1993, which states: 'Cylinder Seal of Cream Stone, 28 x 15 mm. On the right is seated deity on a padded stool, with long beard, wearing a hat with deep brim and a long robe to the feet. One hand is held at the waist, the other is raised with a small cup in it. Before him stands a worshipper, in a similar long robe, but bare-headed, and with the hands clasped at the waist. Behind him is a Lamma goddess, with horned tiara, long flounced robe, and holding up both hands in a gesture of adoration. There is a lunar crescent in the sky. A two-line cuneiform inscription names the seal owner: Bu-zi-ia Buziya / dumu ur-dmes son of Ur-Mes. This is an Old Babylonian seal, c. 1900-1800 B.C., from southern Mesopotamia. Though the surface of the stone is a little worn, the fine quality of the engraving is still present.' 12 grams, 28mm (1"). Property of a West Yorkshire collector; formerly property of a North London collector; acquired in the 1970s; accompanied by an original W.G. Lambert scholarly note. This lot is part of a single collection of cylinder seals which were examined in the 1980s by Professor Lambert and most are accompanied by his own detailed notes; the collection has recently been reviewed by Dr. Ronald Bonewitz. Accompanied by a museum-quality impression. Fair condition. Rare.

We found 209236 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 209236 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

209236 item(s)/page

Late 4th-early 3rd millennium BC. A carved Late Uruk or Jemdet Nasr Period alabaster figure of an elephant, coiled ears, with columnar trunk placed symmetrically between the forelegs. 467 grams, 90mm (3 1/2"). Property of a London gentleman; previously in the collection of Munro Walker before 1970; acquired from Germany in 1962; previously in the Sammlung Holschek collection; accompanied by a copy of a 1962 invoice. Fine condition. Rare.

Late 2nd-early 3rd century AD. A Roman bronze sport helmet of 'Pfrondorf Type' (type F of the Robinson classification of Roman cavalry Sport Helmets, Robinson, 1975, pls.367-375, pp. 126-127), with female features, possibly representing a gorgon (Medusa), comprising a two-part helmet with a back plate, the face piece originally with a removable inner mask; the skull embossed with stylised representations of hair along the sides and collected at the lower centre of the back to a chignon, the centre decorated by a blue enamel stone; on the upper part of the skull a two-headed snake, whose wide body is decorated with scales chiselled on the surface, long neck protruding on the two sides of the skull until the brow; the edge of the skull is decorated by punched triangles and a line representing the crown of the hair around the face; a small flat neck guard; a hinge is fastened through a pin the skull to the mask allowing it to be raised; the T-opening for the face was not always present in this type of helmet. See Robinson, R., The Armour of Imperial Rome, New York, 1975; Garbsch, J., Römische Paraderustüngen, München, 1979; Born, H.,Junkelmann M., Römische Kampf-und Turnierrüstungen, Band VI, Sammlung Axel Guttmann, Mainz,1997; D'Amato R., A.Negin, Decorated Roman Armour, London, 2017; D'Amato R., A.Negin, Roman Heavy Cavalry (1), Cataphractarii and Clibanarii, 1st century BC-5th century AD, Oxford, 2018; this mask helmet belongs to the category of Roman Mask Helmets employed in the sportive games, acting also as military training, of the so called Hyppika Gymnasia described by Arrian of Nicomedia in his Taktika, written down during the age of the Emperor Hadrian (117-138 AD), however, these kind of very simplified masks were often used in battle as well, especially by the heavy cavalry of the catafractarii (D'Amato-Negin, 2018, p.30,36,38-40), the distinguishing features of this type of masked helmet, diffused in the Roman Army since the Late Antonine Age (second half of second century AD) is the removable central area of the mask covering eyes, nose and mouth and the division of the helmet in two parts on the line of the ears; the Pfrondorf specimen (Garbsch,1979, pl.26; Born-Junkelmann,1997, p.50; D'Amato-Negin, 2017, fig.168 a-b), in Stuttgart Museum, which gives the name to the typology, is the most complete and known of such specimens; three parts helmets are known from Danubian sites, like Ostrov (Romania, Robinson, 1975, pls. 370-373; Garbsch, 1979, pl.27), from the German Limes (Oberflorshtadt, Robinson, 1975, fig.129, p.108, D'Amato-Negin, 2017, fig.172c, p.169) and a magnificent specimen, preserved only in the skull, from the collection Axel Guttmann is kept at the Musée d’Art Classique de Mougins (D'Amato-Negin, 2017, fig.172a, p.169); a further splendid specimen, the mask only preserved, is kept in a large private European collection (D'Amato-Negin, 2017, fig.180, p.177"). 2.1 kg total including stand, 27cm (10 1/2"). From an important East Anglian collection of arms and armour; formerly in a Dutch private collection since the 1990s; previously in a Swiss family collection since before 1980; accompanied by a metallurgic analytical report, written by metallurgist Dr. Brian Gilmour of the Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, University of Oxford, report number 144723/HM1364; and an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato; this lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by AIAD certificate number no. 144723-10011. This type of helmet is very rare in such fine condition. Helmets with a facial cut-out have often the female characteristic of Medusa, considering the psychological impact that this creature, with the power to transform men to stone. The apotropaic character of such divinity, inspiring terror on the enemies and confidence to the wearer, was part of the interpenetration of the divine world inside the human world, considered essential for the men who risked their life daily, who needed to feel the protection of the divine beings on the battlefield, or in the travel to the underworld. The main problem of these helmets with face attachment and three-part cutout for eyes, nose and mouth, is the question of the presence of the inner mask. Separate inner masks in bronze are known, some of them silvered (Robinson, 1975, pl.374, p.127, from Stadtpark Mainz), or with slender brows and finely pierced rings in the eye-opening (Robinson, 1975, pl.37,5 p.127, from Weisenberg"). There is no way of ascertaining whether or not our specimen was equipped with an inner mask, though it would appear to be quite possible that it was not, as there are no traces of holes in the point where, in the mask helmets of this typology, the turning pin for the attachment of the mask is usually visible. This suggest that our mask was conceived and used for a more practical use on the battlefield, without excluding its possible employment for the tournaments and the Hyppika Gymnasia. Very fine condition, some restoration. Extremely rare in this condition.

Early 3rd century AD. A sheet bronze mask from a cavalry sports helmet of Heddernheim or Worthing Type with repoussé detailing; the lower edge a flange with ropework detailing, disc to each cheek with whorl pattern, central trefoil void with perforations (breathing holes) to the chin, band of slanting bars above the brow imitating hair; the rim with five groups of attachment holes and lateral tabs to allow the mask to be secured to the outer elements of the helmet, and raised or lowered without removing it. Cf. Garbsch, J. Römische Paraderüstungen, München, 1978 item 53 (Frankfurt-Heddernheim helmet); Robinson, R., The Armour of Imperial Rome, New York, 1975; Born, H.,Junkelmann M., Römische Kampf-und Turnierrüstungen, Band VI, Sammlung Axel Guttmann, Mainz, 1997; D'Amato R., A.Negin, Decorated Roman Armour, London, 2017. 221 grams, 20cm (8"). From an important East Anglian collection of arms and armour; formerly in a Dutch private collection since the 1990s; previously in a Swiss family collection since before 1980; accompanied by a metallurgic analytical report, written by metallurgist Dr. Brian Gilmour of the Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, University of Oxford, report number 144724/HM1361; and an academic report by Roman military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato; this lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by AIAD certificate number no. 144724-10012. The three-part helmets, which form a very important part of the Roman third century helmets, especially of the cavalry ones, have been variously classified by the scholars of the Roman military. Besides the type F of Pfrondorf typology Robinson (1975, pp.126-131) individuated the types G (Hedderneim type) and H (Worthing type"). All three present the characteristic of having a skull and a face mask with a removable central area of the mask covering eyes, nose and mouth. The type G, however, differently from the previous type F, presents a high curved crest on the skull and a front face, imitating that of the Apulian-Corinthian helmets, the type H being of pseudo-Attic shape (Garbsch, 1979, pls.28-29; Born-Junkelmann, 1997, pp.59-63, 106-108; D'Amato-Negin, 2017, pp.106ff., fig.175-181"). The surviving examples of H typology (Worthing helmet, s. D'Amato-Negin, 2017, fig.177 lett.d) suggest the idea that a mask was not always used to protect the face. This could be sometimes achieved by the framed face part of the helmet. In our specimen the missing of the skull does not allow to understand if the face-guard belongs to the Hedderneim or Worthing types: but the missing of fastening elements of the inner mask on the face-guard points towards the second category. According to the classification of M. Kolert, these helmets belong to the III type of mask helmets. The German scholar supported the theory that the main feature of all these helmets was their three-part design and cheek-pieces, or the replacing face part with a cut-out and a mask that was sometimes inserted into it. Most probably this specimen is from a battlefield. The piece is in fine condition. The face-guard is largely complete and comparatively plain. It has an opening in the centre to expose the mouth, nose, and eyes while protecting the brow, cheeks, and chin. The two parts of the helmet were in fact held together either by a hook-and-eye arrangement or a small hinge. Once the two halves of the helmet were in place, they would have been secured to the wearer’s head by lacing at the neck, which was attached to the loops on either side of the neck of the skull. The helmet is relatively scarce in the decoration, but the spiral deserves attention for its connection with the solar cult. The spiral represents the rotary movement of the sun, the spiral is probably the oldest known symbol of human spirituality connected with the sun, together with the swastika or tetragamma. The sun traces a spiral shape every three months in its travels. The connection was also visible in the Celtic art, where the representation of the spiral also follows the path of the sun, describing the movements of the heavenly body over the course of a solar year. The third century was characterised by the great diffusion, among the Roman soldiers, of the solar cult, the Sol Invictus, its symbols often represented on arms and weapons as an apotropaic element of protection. Such cult was diffused especially with the Severan Dynasty, who had connection with the Syria due to the women of the Dynasty, especially Julia Domna, wife of the Emperor Septimius Severus, Julia Mesa, mother of the Emperor Alexander Severus and Julia Soemia, mother of the Emperor Elagabalus. This imperial Syrian family favoured the cult of the Sun, especially in the eastern part of the empire, by building even greater temples in honour of the God Helios, like in the ancient Heliopolis (actual Balbeek) and in Rome. Fine condition, some restoration. Extremely rare.

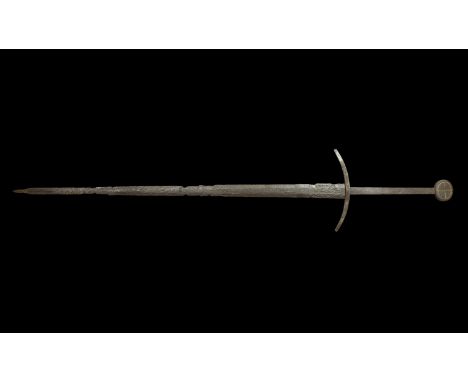

10th century AD. A double-edged Viking Sword of type S, following the classification of the Petersen (1919, pp. 173ff.); with a well tapered double-edged broad pattern-welded blade, with well preserved cutting edges, although traces of battlefield use are clearly visible along the length; the fuller is wide, shallow and well defined, however, ending in the area of the point; the pommel showing the three lobes typical of this category; while the slim guard has boat-like shape with splayed ends formed of solid iron (what it is not characteristic of all guards); two rivets are fastening the short upper guard to the pommel from bottom, with the attachment holes still visible; a beautifully well-balanced weapon. See Petersen, J., De Norske Vikingsverd, Oslo, 1919; Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002. 1.1 kg, 92.5cm (36 1/2"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; believed originally from Stralsund, Germany; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. This sword finds good parallels in similar Viking age specimens, like the one preserved in the Chertsey Museum, England (10th century, s. Peirce 2002, pp.98-99), or the one in National Museet in Copenhagen (10th century, s. Peirce 2002, pp.100-101"). Petersen, among the twenty-two samples of S typology shown, published a similar sword from Arhus (1919, fig.114"). In all these swords, the three-lobe pommel (or the five lobes pommel, like in the specimens of Oslo, River Thames and Søborg Castle, s. Peirce, 2002, pp.102-107) is the main characteristic (s. in particular Petersen, 1919, figs.114-116), although they are sometimes, differently from our specimen, highly decorated in Ringerike style with silver and copper inlays on the guard, hilt and pommel. From the beginning, the Viking swords diversified into a complex array of forms and shapes, many of them showing such fine hilt decorations of carved gold and silver, with shimmering twisted wire accents and inlays. On the swords from Copenhagen and Chertsey are visible also the inscriptions +VLFBERT+T and + MFBERIT + on the blade, showing that many of such swords were produced in the famous workshop of the Frankish and Germanic Empires. Here no inscription is visible, neither traces of decoration have survived on the guard and lower face of the upper guard, although it seems that are suggestions of an iron-inlaid inscription on the blade. If our sword is a river-find, this can be explained with the corrosion of it and the disappearing of the original possible inlaid. The upper guard and the pommel are riveted together, which is commonly observed for this type and most others with two piece upper hilts. It is believed that Type S swords arose in the 10th century from the older type D Viking swords (Petersen, 1919, pp.106-111"). The S types retain the large bulbous central lobe of the D types but have a more semicircular shape. Viking swords of Type S are commonly found in Nordic countries and Eastern Europe, with only a small number found in Western Europe. Our example is in excellent condition. Although there appears to be no certainty with regard to its find-place, our specimen is coming from excavation of a grave or river, where it was deposed and ritually bent. As with other Viking swords, the type S was designed for cutting, not thrusting. The curvature of the wide tip allows for slicing tip cuts. According to Kirk Spencer, Assistant Professor of Science and History at The Criswell College in Dallas, Texas, the pronounced distal taper makes the blade of such swords lively enough for good control and placement, and the thin edge geometry produces very clean cuts through soft targets. Probably such swords would have been less effective against mail armour that would have been seen on the battlefield. The pronounced distal taper would take critical inertia out of the blade producing shallower cuts and the thin edge would be more likely to roll or chip. The hilts of such swords were covered with organic material like leather, ivory, horn, rope. In the sword of Chertsey, upon the robust tang and adjacent to the cross are traces of horn grip. In the sword from Thames the almost parallel tang is completely bound with fine silver wire, like other samples from Scandinavia. At each extremity of the grip of Thames sword there is a circle of plaited silver wire which may well have help to hold a leather grip in place, also. The swords of Viking Age appears in the archaeological record with the enlargement of their pommel caps and the uniting of the sandwiched components into solid upper and lower guards. As a matter of fact, the earliest solid guards even have false rivet heads decorating them. Some of the earlier forms even had beautiful pattern welded blades, preserved also in later specimen, like this one. The style and the decoration on the type S swords are all very different. In the hands of Viking warlords, these magnificent ancient heirlooms must have been breathtaking. In this sense, they symbolise all that is frightening and beautiful in the Viking culture, a culture that is itself a fitting and glorious epitaph to the sword as the magical companion of ancient heroes. Fine condition, some restoration. Very rare.

Mid 10th-late 12th century AD. A long Western European double-cutting sword with Brazil nut pommel and a guard where, unusually, the thin and marked quillons are curved towards the blade, which has a very wide but little marked central groove along its whole length; a silver and copper damascened inscription in capital letters to the fuller, on one side of the blade, on the strong part of it, preceded by a Latin cross, reading: PETRNVS + EO IVSTA NNVS + NC; the weapon is very elegant, with finely tapering and beautifully proportioned blade, thin in section and yet, in conjunction with the somewhat small Brazil nut pommel, able to produce an excellent degree of balance; the fuller and cutting edges remaining extremely well defined. See Petersen, J., ,i>De Norske Vikingsverd, Oslo, 1919; Davidson, H. R. Ellis, The Sword in Anglo-Saxon England, Oxford, 1962; Oakeshott, E., The sword in the age of the Chivalry, Woodbridge, 1964 (1994); Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002; Gilliot, C., Armes & Armures V-XV, Bayeux, 2008. 984 grams, 93cm (36 1/2"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. This sword belongs to the type XI of the Oakeshott classification. This type is characterized by a long, narrow blade, sharply contrasting with the broad, short blades of Type X, the edges running parallel for about two thirds of the blade's length, then tapering in subtle curves to an adequate point. The fuller is narrow, often very shallow and poorly defined, and runs four fifths of the blade's length, sometimes (in later examples) beginning in the tang within the hilt. The cross in most surviving examples tends to be straight and of rectangular section, but examples with curved quillons are not unknown, like in our specimen. With respect to the actual topological development of the type, it is evident that the taller, slimmer pommels were the early ones, and the small, thick, blunt pommels were the later ones. We note that, with the smaller, thicker pommels follow the longer lower guards, that sometimes are slightly curved. In particular we shall here note sword C 12217 from Sandeherred (Petersen, 1919, f. 129), where the transition to medieval swords has already begun, the pommel’s underside already begun to become convex [being the earliest stage of evolution towards the Brazil-nut pommel], and the cross-guard being decisively curved. The majority of pommels are of the various Brazil-nut forms, though a good many have disc pommels. A few have thick disc pommels with strongly bevelled edges (Type H - see chapter III"). The tang is short, generally with parallel sides, and not so flat as in the Type X swords (Oakeshott, 1964 (1994), p.32"). The sword finds good parallels with various swords of the same typology. The beautiful sword from Padasjoki, Finland, second half of 10th century (Peirce, 2002, pp.122); a sword in a private collection, from mid 10th to early 11th century (Peirce, 2002, pp.124-125); the sword of the Musée de l'Armée, Paris, from mid 10th to mid 11th century (Peirce, 2002, p.131"). We should not forget a similar 12th century German sword published by Gilliot (2008, p.121) reporting also the inlaid inscription SPES MEA JESUS PER OMNES... (Jesus my hope amidst all trials..."). Another, also published by Gilliot (2008, p.121), a German or North Italian work showing the same almond pommel and slightly curved quillons. Although fitted with a different pommel, a sword of this typology (dated from late 11th to early 12th century) from Marikkovaara, Rovaniemi, Lapland (Peirce, 2002, pp.134-135) shows the identical delicately sculptured cross with a gentle curve towards the blade visible in our specimen. This type has generally been considered to belong to the period c. 1120-c. 1200–1220, but recent research has given it a much earlier date. Most probably our specimen is from a battlefield or from a grave. The piece is in excellent condition. The well formed Brazil-nut pommel and the long, almost imperceptibly curved cross are both of a form hitherto held to be of a date no earlier than c. 1100, but there is actually plenty of evidence that they were in use, particularly in England, during the 10th century (Davidson, 1962"). Several English manuscripts, date-able within that century, show long, slender swords (Oakeshott, 1964 (1994), fig.12) with hilts much akin to this example; in some cases the cross is extremely long, and very sharply curved. There is a pommel, too, in the British Museum, found at Ingleton in Yorkshire with a mount of inlaid silver gilt and decorated in a typically English style of c. 900 which is - or was, for the iron part is much corroded - very similar indeed in shape to the pommel on the category of swords in question, and to those in the manuscripts referred to. The inlaid letters of the inscriptions in these Type XI are very much smaller than the ones in type X, and so appear to be neater. This smallness and apparent neatness has caused scholars to assume that these inlays are a progression from the cruder, earlier ones, and are thus later in date. But correctly Oakeshott has demonstrated that they have to be smaller, for they must be fitted into a very narrow fuller, not allowed to sprawl over a very wide one. Fine condition. Very rare.

Circa 1300 AD. A German great helm in a poor state of preservation, but still visible in its original shape without deformation; composed of five rivetted plates: two forming the top, two the front, and one the back; the top of the helmet is convex; the visual system is divided into two, and on both left and right parts, are distributed the various holes forming the ventilation system. See Demmin A. Die Kriegswaffen in ihren geschichtlichen Entwicklungen von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart. Eine Encyklopädie der Waffenkunde, Gera-Untermhaus, 1891; Müller-Hickler H., 'Über die Funde aus der Burg Tannenberg', ZfHW XIII, in Neue Folge 4, 1934, pp.175-181; Žákovský P., Hošek J., Cisár V., A unique finding of a great helm from the Dale?ín castle in Moravia, in Acta Militaria Medievalia, VIII, 2011, pp.91-125; Gamber O., Geschichte der mittelalterlichen Waffen (Teil 4), in Waffen- und Kostümkunde 37, pp. 1-26; Scalini, M., A bon droyt, Spade di uomini liberi, cavalieri e Santi/Epées d'hommes libres, chevaliers et saints, Milano, 2007. 1.4 kg, 25.6cm (20"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. According to the current knowledge, great helms began to generally appear in the arsenal of western medieval warriors in Western Europe as early as the beginning of the 12th century (Žákovský, Hošek, Cisár, 2011, p.91"). It is not easy to understand which was the medieval word designating such category of helmets. The terms helmvaz and helmhuot, used for instance in the German epic Nibelungenlied, refer probably to large and closed helmets. Some authors therefore associate the origin of great helms with the German lands. The theory can be supported by the fact that most European languages adopted the term for this type of helmets from German helm or great helm in English; heaume in French; elmo in Italian, and yelmo in Spanish (s. Demmin, 1891, pp.492-493; Müller-Hickler 1934, p.179; Gamber, 1995, p.19"). In sources written in Czech, the candidate terms referring to great helms seem to be p?ilbice and the derivative of the German word, helm. The typological evolution of the 14th century in Germany, takes the name of kübelhelm. The general development of great helms was starting in the early 13th century, based on round shapes with straight sides and a flat occipital plate with a distinct edge. They are known, because of the preserved beautiful aquamaniles (Scalini, 2007, pp.132-133, Aquamaniles from Lower Saxony, about 1300 AD; Žákovský, Hošek, Cisár, 2011, p.95, fig.4"). The subsequent development involved larger helms of oval cross-section with a distinctive edge. These helms reached to the shoulders of the wearer and the top was already convex. The helmet here represented should be added to the few survivingv specimens, as it is a good parallel with the great helm from the castle of Tannenberg, dated at the second half of the 15th century. The ventilation system, however, is more similar to the helmet from Dalecin (Žákovský, Hošek, Cisár, 2011, fig.5, p 95, 7, p.97), recently published by Bohemian archaeologists and discovered in 2008 by accident. The top of the helmet is similar to the helmet of Altena (Žákovský, Hošek, Cisár, 2011, p.110, fig.18b"). These great helms of traditional design, and especially those with a convex top, whether of five, four or three plates, are in general believed to have been manufactured in Germany, although any direct evidence is missing (see Boeheim 1890, 29; Pierzak 2005, 31"). Žákovský, Hošek, Cisár believe that the current state of knowledge is not sufficient for determining even the approximate location of their origin. The possibility that some of the known helms were manufactured close to where they were found, cannot be ruled out either. Moreover, it is not likely that the design patterns and details can be used to date the individual specimens at the moment. This is mainly due to the fact that only a small number of great helms have been recorded so far and that most iconographic sources, which could be useful in making the dating estimates, and our knowledge of great helm development more accurate, are rather simplified or the important upper parts of the depicted helms are covered with mantling and jewels. Most probably our specimen is from a castle excavation. The piece is in fair condition and considering the rarity, a high start price can be expected. These helmets are generally thought to be dressed over the chain mail of the hauberk, and supported inside by an internal padding called 'padiglione' in Italian. An example from Tannenberg was unfortunately destroyed during the First World War. The find is quoted, but not illustrated by Demmin (1869, p.276, n.54) who states 'Deutsche Kesselhaube vom Ende des 13. Jahrhunderts, unter dem Schutte des im 14. Jahrhundert eingeäscherten Schlosses Tannenburg gefunden, von welchem Hefner v. Alteneck eine Abbildung herausgegeben hat' meaning: 'German great helm of late 13th century, found under the rubble of the 14th century cremated castle Tannenburg, of which Hefner Von Altenek has an illustration'"). For the weight and the encumbrance of such big helmets were worn only in the imminence of the battle, leaving it, when not in use, suspended by a breast chain fixed on the front but hanging behind the shoulders. In the Tannenberg specimen there is still a small cross-shaped opening on the left side of the frontal part of the helmet, used to allow the passage of a small attachment for the chain which fastened the helmet to the breast part of the armour. The main elements of the knight's protection were helmet, shield and armour, and when the helmet was not necessary and limited the view, was put away. Sometimes, as visible on the splendid Manesse Codex, the helmets were surmounted by a decorative plume or crest, made of organic material like parchment, cuir bouilli, papier-mache, wood or copper sheet. Fair condition. Extremely rare.

Circa 1340 AD. A Western medieval cervelliere's or early bascinet skull in iron, probably Italian, the dome bowl following the shape of the skull, narrower on the front and wider at the occipital bone; the protection of the area is wider than in the usual cervelliere, and all around the rim of the helmet the fastening holes to the inner felt or leather lining, or the sewing to a textile cap, are visible. See Boccia G.L., Rossi F., Morin M., Armi e Armature Lombarde, Milano, 1980; Nicolle, D., Italian Medieval Armies, 1300-1500, London, 1983; Vignola, M., I reperti metallici del castello superiore di Attimis, in Quaderni Friulani,di Archeologia, XIII, 2003, pp.63-81; Scalini, M., A bon droyt, Spade di uomini liberi, cavalieri e Santi/Epées d'hommes libres, chevaliers et saints, Milano, 2007. 881 grams, 22cm (8 1/2"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. The cervelliere was a very common skull protection since the 13th century Italy, made of metal and shaped like a simple skull. It (from Latin cervellerium, cerebrarium, cerebrerium or cerebotarium) was a helmet basic typology developed in Middle Ages. It was made of a single piece of cup-shaped metal covering the top of the skull and could be worn over or under the hauberk and other typologies of heavier helmets. Over time, the cervelliere experienced several evolutions. Many helmets became increasingly pointed and the back of the skull cap elongated to cover the neck, thus developing into the bascinet. The skull protection of our specimen has parallels with the helmets worn by the warriors represented in the killing of the innocents painted in the Church of Saint'Abbondio, Como, dated at 1340 AD (Boccia, Rossi, Morin, fig.10 pp.30-31), which Boccia correctly classified like cervelliere. This specimen is therefore still a cervelliere, or eventually an early form of bascinet of which the cervelliere was the ancestor, although this specimen begins the transformation of the simple skull in the wider bowl that, fitted with a peak, will give origin to the bascinet. Its conformation distinguishes it from the various similar head protections classified as bascinet in the 15th century. The statement that we are still dealing with a cervelliere is based on the morphological data of the object. The shape, above all, is markedly hemispherical, tightening towards the front and falling slightly on the nape. A similar skull is visible on the cerviellere found in the castle of Attimis (Italy, Trentino Alto-Adige), recently published by Vignola (Vignola, 2003, pp.66 ff."). Differently from the usual cervelliere, the bowl shows side protections, and the sides are protecting also the ears, which is not the characteristic of the usual cervelliere. The type then turned out to define in anatomical way and adherent to the skull. Another characteristic trend is the series of holes visible all along the lower edge, from front to the neck. Correctly Vignola suggested, by analysing the specimen of Attimis, that such parallel holes were destined to receive the sewing, to fasten the helmet with a falsata (padded or quilted headgear"). The presence of similar holes in the other helmets of the same category was absolutely fundamental to allow a similar helmet to be worn, as well as to absorb the trauma of a stroke directed towards the plain surface of the cervelliere skull. The falsata had probability the possibility to be fitted with stripes for the protection of the nape, and of thongs to fasten the helmet under chin, too. Moreover, a cap was sometimes worn over the helmet, forming an external textile headgear prolonged over the ears (Nicolle, 1983, pl.B2), often visible in the iconography of the period and considered like a civilian cap by many art historians not particularly skilled in the military equipment study. Most probably our specimen is from a battlefield or a river find. The piece is in good condition and considering the rarity a high start price is expected. Under the profile of the chronology such protections for the head had a long life, from 13th until 16th century, however, conforming with the date proposed by Vignola for the piece of Attimis, the specific morphology of the helmet found precise elements of comparison with the 14th century iconography. By looking at the helmet from the sides, it shows a typical gleaning towards the lower edge, raising to the brow part. This is visible on many cervelliere and bascinets of the 14th century, on the prototypes visible in the so-called biadaiolo (code of the mid-14th century) of the Medicean Laurentian Library in Florence, in the already quoted frescoes of Saint Abbondius and even in some cervelliere represented in the Manesse Code. The ancient sources call such type of objects bascinet, having the shape of a basin or basin without lip, although the shape of the helmet that is modernly designated with this name, has a rather ogival shape as for the head gears of the second half of the fourteenth century. Cervelliere or early bascinets like our specimen, may be dated to the first half of the 14th century, but the formal adherence to the progression of the skull makes it difficult to secure a chronological staggering. However, an artifact examined by Scalini, datable to 1330, from Perugia, shows protective side parts like this specimen, which descend to protect the ears, and allowed also a more comfortable overlap to the knitted shirt. This specimen was used to draw water from a well, until that is was not recognised for its importance. (Scalini, 2007, pp.106-107"). Anecdotally, medieval literature credits the invention of the cervellière to astrologer Michael Scot (Michele Scoto) in 1223. This history is not seriously entertained by most scholars, but in the Chronicon Nonantulanum is recorded that the astrologer devised the iron-plate cap shortly before his own predicted death, which he still inevitably met when a stone weighing two ounces fell on his protected head. Fine condition. Extremely rare.

Late 14th-early 15th century AD. A long Western European two-handed sword of German origin, the pommel, circular (type H1 or H2), is mounted on a guard and presents a latten inlaid cross within a circle, the cross guard style, curved, corresponding to type 1; the hilt is formed by a hand-and-a-half grip; the blade, tapering sharply, is of hexagonal section, well enough preserved beneath the smooth, richly dark patina of Goethite, with no significant pitting in any part, but the sides of the blade are showing strong corrosion and damage due to the actual use on the battlefield; the shallow fuller is running about one third of the length; beautifully balanced and ready in the hand. See J. Oakeshott, R.E., The Archaeology of the weapons, London,1960; Oakeshott, E., Sword in hand, London, 2001; Oakeshott, E. Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991. 1.8 kg, 1.33m (52 1/2"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. This sword has good parallels in various similar specimens (Oakeshott, 2001, fig.106), ranging from the second half of 14th century to 1450 AD. The pommel recalls at least two swords preserved in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, one of them presenting also a similar but less curved crossguard (Oakeshott, 1991, pp.161-162"). A third sword in the Philadelphia Museum shows instead a complete identical cross-guard (Oakeshott, 1991, p.164), but a completely different pommel. The blade is very similar to that of a specimen once in the Oakeshott collection, and now in the Nationalmuseet of Copenhagen (Oakeshott, 1991, p.160"). Swords of this type all have the same bladeform, but considerably varied hilts, and examples have been found all over Europe. Many survive; perhaps the finest of them all is one which was found in the River Cam, preserved now in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge (Oakeshott, 1960, pl.16c"). Another very important specimen, second only to the Cambridge example, with a similar blade but a totally different hilt was, at the times in which Oakeshott wrote his Archaeology of the Weapons, in a famous and very choice private collection in Denmark. This is one which was put in the Hall of Victories at Alexandria, presumably as a trophy, by the Mamluks. There are many such trophies, swords of Italian fashion and of fourteenth-century types, with Arabic inscriptions applied to their blades after being deposited in this Arsenal by the Mamluk Sultans of Egypt. Some were probably acquired as gifts from merchants or embassies from Genoa, Pisa or Venice, but others are undoubtedly the spoils of war, captured from Christian forces based on Cyprus. In 1365 one such force (under Peter of Lusignan, titular King of Jerusalem) made an attack upon Cairo. It was beaten off, and several swords bear witness to Peter's defeat. Type XVII is characterised by being, in first instance, a big 'bastard' sword, with no samples of short-grips. It was a long 'Sword of War'. The flat round/oval pommel appears here as in the most part of the samples of such category (the 75%), and because the pommel shape and decoration, the sword can still be included in the chronological framework of the second half of XIV century, without excluding the first half of XV century. The noteworthy element of this sword is its pommel with the inlaid cross. The presence of the cross suggests the belonging of the weapon to some military order of Chivalry. Considering that the Templars were destroyed at the time in which our sword was made, the main candidates could be the Hospitallers or the Teutonic Knights. Or even, the sword could have belonged to some warrior who decided to take part to the crusade expeditions against the Turks. Blade and handle is well preserved. Most probably our specimen is from a battlefield or a river find. The evolution of the armour, in the western Europe of 14th century, shows an ever-increasing amount of defensive pieces. With an increase in the effective use of archers and foot soldiers beginning early in the XIV century, the largely mail-clad mounted warrior began to show an unprecedented level of vulnerability. In response to this, quite logically, was to augment the typical defences of the early 14th century (a mail suit, iron helm, and early plate defences for the legs) with additional plates of iron on other parts of the body. These plates were strapped over the existing mail, adding protection, in varying amounts, to the upper extremities and the torso. While these changes may have added some level of protection against foot soldiers and arrows, they had the effect of rendering older-style cutting swords ineffective against anyone wealthy enough to afford one of these so-called transitional harnesses (the transition being between basically mail only and full plate harnesses"). The difficulty encountered in wounding someone dressed like this led other weapons to rise in favour, most notably impact weapons like the mace, axe, and war-hammer. This comported in a parallel way the change in the making of the swords, creating types like the XVII, which ranged from 1350 to 1425-1450 circa, with some specimen reaching even the dawn of the 16th century. The sword had to change to retain its effectiveness on the battlefields. To combat the armour of the time, it was necessary to make greater use of the thrust to find vulnerable gaps and joints in an opponent's defences. The flat lenticular cross-sections so popular on earlier swords were not well-suited to the thrust, since they gave the blade a necessary measure of flexibility to aid the cut. The wide tip sections needed for heavy cleaving were also an impediment to thrusting. Different cross-sections and blade profiles, therefore, needed to be developed to give the stiffness and the proper tip shape required for thrusting. This was the combination which gave life to the swords of this typology: swords with a pronounced hexagonal section to add stiffness to the blade, of hand-and-a-half proportions, to take advantage of the extra power and manoeuvrability given by the addition of the second hand to the grip. Fine condition, repaired. Very rare.

Mid-late 14th century AD. An iron longsword of Oakeshott's Type XIIIA. 10 or 13 (Oakeshott, 1991, pp. 105-106), the cross style a variant of 2, pommel type K; a two handed sword showing a round bevelled pommel and a straight guard with square-section quillons; the double-edged blade showing a short marked groove extending for only a third of its length; a cone-shaped roundel is visible between the pommel and the flattened end of the tang; some evidence of fighting, although both sides are well preserved in their complex. See Oakeshott, E. The sword in the Age of the Chivalry, Woodbridge, 1964 (1994); Oakeshott, E. Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991; Oakeshott, E., Sword in hand, London, 2001; Gilliot, C., Weapons and Armours, Bayeux, 2008. 1.6 kg, 1.11m (43 3/4"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; believed originally from near Dresden, Germany; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. This sword, belonging to the type of 'Grand espée d'Allemagne', or sword of war, is similar to a German work recently published by Gilliot (2008, p.122"). It introduces to the typologies of swords used in the two-hand fighting. Swords of such dimensions in fact, may legitimately be considered as two-handed. In numerous inventories, literary references, wills of 13th and 14th centuries, it is clearly described the function and the employment of such swords. The famous chronicles of Froissart, who described the tremendous period of the Hundred Years War (Chronicles of England, France and Spain) gives a vivid and lively (and not absolutely fictional) account of the use of such weapons during the first part of the war, between 1340 AD and the end of the 14th century, so describing a militant churchman, a certain Canon de Robesart, in 1358: ...il tenoit une espée a deux mains, dont il donnoit les horions si grande que nul les osoit attendre.... (he held a sword of two hands, with which he gaves strokes so great that none dared faced them"). The Grete swerd of type XIIIa could be used with two hands, and according to Oakeshott the 14th century twahandswerd was just an extra-large Grete swerd of this typology (Oakeshott, 2001, pp.96 ff."). Also another important document of this period, the Chronicle of Du Guesclin said that ...Olivier Manny le fere tellement d'une espée à ll mains, qui tranchoit roidement (Olivier de Manny struck in such a way with a two-hand sword, which sliced keenly)...' Last but not least the mentions of such swords is clearly reported in the legal documents, acts of will and donatives of the period, like for example the will of Sir John Depedene, which contains in 1402 the mention of 'Unum gladium ornatus cum argento et: J. Twahandswerd', i.e. of a 'one sword decorated with silver and one two hand sword'. The double hand sword is illustrated in famous manuscripts, like the Tenison Psalter of 1284, where a miles (knight) covered by a great helm is brandishing with two hands a sword of type XIIIa (Oakeshott, 2001, p.98"). According to Oakeshott there is a basic distinction between the 'Grete Sword' and the Twahandswerd. When we think about it we have on mind the enormous two-handed swords, distinctively shaped and highly specialised, of XVI century. But they were instead just a variant - maybe determined with a longer grip which made easier the two hands fight - of the usual great German war sword. This statement must be examined in detail. In the literature of the late 13th and early 14th centuries we find many references to these 'espées de guerre', 'Grant espées', 'Grete Swerdes', and so on. In art of the same period we find many portrayals of very large swords of Type XIIIa, and there are a considerable number of survivors. In the late 13th and the 14th finds and literature we find many references to such 'espées de guerre', 'Grant espées', 'Grete Swerdes', and so on. At the same time the art of these two centuries provided the better iconography of them. The references to 'Grete Swerdes' do not, I believe, indicate two-hand swords, for these are always described as such, as 'espées a deux mains'' or 'Twahandswerds', and need not be confused with the sword of war. The two-hander of the 13th-15th centuries was not, as in the 16th, a specialised form of weapon; it was just a larger specimen. Most probably our specimen is coming from a battlefield or, most probably, a river find. The piece is in excellent condition. The swords of type XIII, to which such specimen belongs, have the following characteristics, well resumed by Oakeshott in his work of 1964 (p.91): A broad blade, nearly as wide at the tip as at the hilt. Most examples show a distinct widening immediately below the hilt, thereafter the edges run with an imperceptible taper to a spatulate point. The fuller generally occupies a little more than half of the blade's length. The grip is long in proportion to the blade—average length 6. The tang may be flat and broad, tapering sharply in its upper half towards the pommel, or it may be of a thick rectangular or square section, giving the appearance of being thin and stalk-like when seen in elevation. The pommel may be of any type, though on most surviving specimens Types D, E and I are the most common (the developed late Brazil-nut forms or the so-called 'wheel' form"). The cross is generally straight, though there are a few curved examples. The variant XIIIa, to which our specimen belongs, is generally the same shape as the simple Type XIII, only much larger. The blade, of similar form, is generally from 37 to 40 long, while the grip ranges from 6½ to 9 in length. Fine condition. Rare.

10th - mid 11th century AD. An iron sword with narrow two-edged blade, gently tapering profile with shallow tip, no appreciable fuller, parallel-sided lower guard, short tang and 'tea-cosy' pommel, tiny and yet more precisely formed, being of 'tea-cosy' type transitional to a 'brazil nut' style pommel; the acutely tapered line of the blade makes the blade very elegant, although the fuller, probably existing ab origo, is practically no more visible; the pommel is in excellent state of preservation with some small areas of light pitting; the hilt is plain, carrying no form of decoration; the cross-guard is simply a gently tapering bar of iron, crudely pierced to take the long and robust tang; battle signs visible on the sides, however the cutting ends remain well defined, especially towards the proximal end of the blade, all the components, considered as a whole, create an effect of harmony, balance and quality. See Oakeshott, E., The Sword in the Age of the Chivalry, London,1964 (1994); Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002; cf. Oakeshott, E. Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991, item X9 (Glasgow Museum"). 891 grams, 91.5cm (36"). From the family collection of a South East London collector; formerly acquired in the 1960s; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.This sword was produced in the workshops of the Holy Roman Empire, with good parallels with various sword published by Peirce (2002, cat. NM2033.1, pp.122-123; NM 11840, pp.132-133"). Especially the sword from Vammala (Finland), in the Suomen Kansallismuseo in Helsinki, shows a great similarity with our model. This latter is however inscribed, like the majority of swords of this category, unlike the current example. The type Xa was in use for a much longer period than the Type XI cavalry swords, whilst the thinner fuller may at first glance appear insignificant - in reality, it marked a serious departure point from the Viking era swords, and were used by late period Vikings, Normans, Anglo-Saxons, Crusaders and Templars, before eventually falling out of favour in the 14th century, when this type of swords began to be quite ineffective against the increasing use of plate armour on the battlefield. On the Bayeux tapestry, there is a depiction of William the Conqueror with a sword of type Xa having a 'tea cosy' pommel, sign of the great diffusion of such kind of sword among the Normans. It is evident that this type was not originally Nordic (in sense of a Viking production), even if it was forged here at home. Besides, it was found in such large quantity, and it was plain in its form. It did exist not only over the whole of Norden but over the whole of Central Europe. It was a common Germanic type in Central and Northern Europe created during the couple of centuries preceding the Crusades, and having a great success until the end of these. Most probably our specimen is from a battlefield, a river or from a grave. The piece is in excellent condition notwithstanding the corrosions of the blade, where signs of battlefield are visible. Originally Oakeshott Type Xa swords were classified by him in the category type XI, but later revised as Oakeshott felt that they deserved their own subcategory, as they were too close to type X to fit within the Type XI category, although the narrower and deeper fuller could not be ignored. However, it was not just the fuller that guided his decision, but the placement of such swords in their historical context, as all existing examples dated from the 11th to the 14th century, while type X started and finished two centuries earlier, from the 9th to the 12th centuries. Like the parent group type X, these were a transitional sword - similar in shape and style to the Viking Age swords that it evolved from - and a stepping stone to the Type XI cavalry swords, which shared the same thin fuller, but had longer, more slender blades better suited to mounted combat. The type Xa presents a broad, flat blade of medium length (average 31) with a fuller running the entire length and fading out an inch or so from the point, which is sometimes acute but more often rounded. The fuller is generally very wide and shallow, but in some cases may be narrower (about 1/3 of the blade's width) and more clearly defined; a short grip, of the same average length (3¾) as the Viking swords. The tang is usually very flat and broad, tapering sharply towards the pommel. The sturdy massive tang provided tremendous strength to the hilt of these long double weapons. The cross - generally of square section, about 7 to 8long, tapering towards the tips, in rare cases curved - is narrower and longer than the more usual Viking kind—though the Vikings used it, calling it 'Gaddhjalt' (spike-hilt) because of its spike-like shape. The pommel is commonly of one of the Brazil-nut forms, but may be of disc form like in this case. The sword appears in two variants, of which the one here presented is the most later and most common. The older variant has a taller and slimmer pommel, while the cross-guard is thicker in profile and slightly curved. The later and more common of the two variants has a lower and thicker pommel and a less thick but longer cross, which can reach even 18 cm of length. The cross-section of the hilt is here evenly wide, with rounded ends, and not cut sharply across, which is otherwise usual with type M. The first group has upper hilts that can reach a length of 7.8 cm. and a height of 5.1 cm. The second group has pommels with a length between 5.0cm and 6.5cm, the height is from 2.7cm - 3.5cm. The lower guard varies in length between 10.7cm to an entire 17.7cm. The height in the first group is up to 2.0cm and in the second group from 0.7cm to 1.4cm. I know 49 specimens of this type. Of those, the later variant is decidedly the most usual. At the time of the Petersen's book in 1919, of the first group there were namely only nine specimens, and 40 specimens of the second group. Of 47 blades identified by Oakeshott, 45 were double-edged and only two single-edged, both from the pronounced 'single-edged' Vestland. Fine condition.

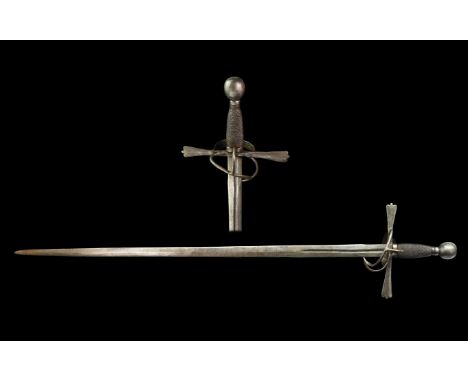

Circa 1500-1540 AD. A 'hand and a half' or 'Bastard' sword, with ring guard, double-edged broad blade, lenticular in section, with single short shallow fuller, running up the first third of its length; the hilt is complex with spherical pommel (style G), the grip is elegantly wrapped with a later iron wire, the cross-guard (style 5) is broad towards the edges, where the iron quillons are ending with three small notches; the handle with a side guard together with the knuckle bow, showing two additional rings on the lower part of the hilt, bowing towards the flat undecorated blade. See Schneider, H., Waffen in Schweizerischen Landesmuseum, GriffWaffen I, Zurich,1980; Talhoffer, H., Medieval Combat: a Fifteenth-Century Illustrated Manual of Swordfighting and Close-Quarter Combat, by Rector, M. (ed."). London, 2000; Oakeshott, E., Sword in hand, London, 2001; Scalini, M., A bon droyt, spade di uomini liberi, cavalieri e santi, Milano, 2007. 1.3 kg, 1.05m (41 1/4"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; believed originally from Liege, Belgium; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. By the second quarter of the 16th century, the long sword had become the 'Bastard' or 'hand and half sword', of which there are many beautiful surviving examples in excellent condition (Oakeshott, 2001, pp.137ff., figs.123-126), like the one here illustrated. The evolution of great and arming swords brought to the transformation of it in the Renaissance rapiers. The samples published by Oakeshott and kept in private collections, show how the developed hilt of the arming sword, which eventually become a rapier, was paralleled in the big 'bastard' swords. Held either in one or both hands, and also known as a ‘bastard’ sword, as its grip was not as long as a traditional two-handed sword, it can be dated to around 1500-1540 based on the decoration of its hilt. The three-notch ends of the crossbars (quillons) are quite flimsy while the finely spherical pommel recalls the swirling lobes that decorated contemporary flagons and candlestick stems. This appearance demonstrates a move away from the brutal simplicity of the medieval sword. The term 'bastard sword' was not, as supported by some scholars, a modern term, but already widely spread in the first half of 16th century. As a military weapon, it was kept in use by the Swiss for almost a century, with very few variations in shape, because it adhered perfectly to the organisational logic of the cantonal troops. So much so, that hundreds of specimens of this type are known, obviously with variations and best represented in the Swiss museums, especially in Zurich (Schneider, 1980, nn. 183-186, 190-195, 198, pp. 129-132, 134-136,138"). Many of them having complex hilts. This interesting piece belongs to the early period of diffusion of rapier in England. With all probability from a battlefield, a castle or a military site. The hilt and spatulate quillons and semi-basket guard for the knuckles is characteristically middle of the 16th century German. It was a long-term employed form, based on the shape of the swords used from horseback, hybridizing them with those of two-handed swords, thus defining an infantryman's sword, very effective against horsemen and pikemen. Its use, predominantly Germanic, involved training and a particular way of shielding, with guard positions, parades and lunges, all different from those of civilian side arms (Scalini, 2007, p.244"). Swords like this were among the most versatile weapons of the battlefield. It could be used one-handed on horseback, two-handed on foot; different techniques were used against armoured and unarmoured opponents; and the sword could even be turned around to deliver a powerful blow with the hilt. Mastery of the difficult physical skills of battle, was one of the chief attributes of the aristocrat. The art of combat was an essential part of a nobleman's education. Sigund Ringeck, a 15th-century fencing master, claimed knights should 'skilfully wield spear, sword, and dagger in a manly way.' These swords, gripped in both hands, were a potent weapon against armour before the development of firearms, but also continued to be used for long time after the diffusion of the guns and arquebuses on the European battlefield of XVI century. To fully appreciate the sword’s meaning for Ringeck as a sixteenth-century gentleman, it is important to understand its double role as both offensive weapon and costume accessory. As costume jewellery the decorative sword hilt flourished fully between 1580 and 1620. However, the seeds were sown long before. This ‘hand-and-a-half’ sword for use in foot combat carries an early sign of this development. No part of a medieval sword was made without both attack and defence in mind. Modern fencing encourages us to see the blade, in fact only the tip of the blade, as the sole attacking element of a sword and the hilt more as a control room and protector. Tight rules prevent the sword hand ever straying from the hilt and the spare hand from getting involved at all. This is a modern mistake. The fifteenth-century Fightbook published by the German fencing master, Hans Talhoffer, illustrates a more pragmatic approach as how two fashionably dressed men settle their differences using undecorated swords with thick diamond-section blades. The blades could be gripped as well as the hilt. The rounded pommels at the end of the grip, and at the ends to the quillons, not only balanced the swing of the sword but acted as hammerheads to deliver the ‘murder-stroke’. As soon as these elements ceased to be functional, they took on the role of adornment. This sword hints at the more decorative hilts produced later in the late 16th and 17th centuries. Swords themselves varied in weight and so did the crossguards. Also there are multiple different crossguards in this category, starting from simple ones with a single sidering or none at all to some complex 'baskets'. Fine condition. Rare.

Circa 1075-1155 AD. An original Viking iron blade of Oakeshott's Type XII, variant 12 (Oakeshott, 1991, p.81), reused with Type XIII, variant 1 hilt, and a T2 pommel (Petersen type Z Viking sword); the double-edged sword has a broad, flat, evenly tapering blade, acutely pointed and magnificently preserved to give an unusually fine balance to its user; the fullers are well defined, deeply cut into the blade to a depth of approximately 1.5mm, divided in three parallel lines extending from below the guard for a little less than half of the blade's length; it is followed by the image of an inlaid beast (a unicorn? a wolf?) chiselled neatly into the surface; the grip is still retaining part of a later leather cover; the style of cross-guard is unusual, and the later pommel is from the T2 category. See Oakeshott, J, R.E., The Archaeology of the weapons, London,1960 (Woodbridge, 1999); Oakeshott, E., The sword in the age of the Chivalry, Woodbridge, 1964 (1994); Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002; Oakeshott, E. Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991; Scalini, M., A bon droit, spade di uomini liberi, cavalieri e santi, Milano, 2007. 1.2 kg, 1.02m (40 1/4"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market via Flicker, inv.1152, classified as Saint Maurice's sword; accompanied by an academic report written by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. This sword, although it can be classified belonging to the XII-XIII groups individuated by Oakeshott (1964 (1994), p.37) resembles, with its singular guard and cross-guard, the famous sword of Jaxa of Miechow, at the Bargello Museum, Florence (Scalini, 2007, pp.111-113, cat.13"). The guard and cross-guard are identical, missing only of the highly decorated elements of the Polish sword. They are a derivation from the typology of the hilts visible in the Petersen group Z, as it is possible to see on the swords from Vesilahti, Finland (Peirce, 2002, p.127, mid 11th century) and Canvick Common, in the Norfolk (Oakeshott, 1991, p.81, dated 1050-1100"). It shows identical hilt with a beautifully-wrought, 11th century Viking sword, that was discovered in 2011 by the archaeologists who were excavating in the Setesdal Valley in Southern Norway. It is clear that the Slavic or Germanic craftsman who made the hilt continued a local tradition derived from the Vikings. Certainly the fact that only few swords existing in the world are showing such particular cross-guard is symptomatic of a local production, and can help to locate the first core of the sword in the Eastern Europe, where also the successive addition could have been made. The cross-guard and the blade are in an incredible state of preservation and we can exclude that they have been ever inside a grave. Maybe, similarly to the sword of Miechow, also this weapon has represented more of a symbol of familiar ownership than a weapon used on the battlefield. Most probably our specimen is a family treasure. The piece is in excellent condition. The sword’s hilt was made in the late 11th or early 12th century, or even at the end of the century, but was with all probably re-adapted to a successive blade presenting the three fullers typical of the Oakeshott XIII.1 typology (Oakeshott, 1991, p.96"). Also the leather covering the grip is probably a further addition from the Renaissance Age (like the leather covering of the grip in the Miechow sword), while the T2 pommel was adapted to the sword possibly in a period comprised between 1360-1420 AD, when the employment of such pommels was very widely spread (Oakeshott, 1994, p.105"). The shape of the sword seems to point also to the typology XIV.7 of the Oakeshott group, and in particular to a sword of the Oakeshott collection (1960, pl.9c; 1991, p.123) dated at 1300 AD. Here the blade tends to be broad, but particularly characteristic are the three deep fullers, punched twice on each side, which seem to be in common use until the XVII century. Interestingly, the small animal punched on the blade seems to be a 12th or 13th century engraving, which will support the idea that the blade could be the original one. The image corresponds near perfectly with the one of the 'Wolf of Passau', i.e. of the image of a 'running wolf' made by the blacksmiths of Passau (Oakeshott, 1960, p.223, fig.105a"). If the blade was made in a Polish or Slavic workshop, its identification with a wolf could be possible, and the linking of the Miechow sword with Jaxa Von Köpenik links also our specimen with the German medieval world. The decoration of the Miechow sword represents an ox or a bull, or even a cow, but it is connected with the heraldry of Jaxa Von Köpenik. It is not impossible therefore to speculate that the engraved running wolf of our sword was in some way chosen because it was the owner's family emblem, or simply because the 13th century blade was done in Passau. During the thirteenth century blade-smiths began again to inlay their products with maker's marks. It is generally possible to distinguish 'trade-marks' from religious symbols. After going out of use for 800 years, it suddenly became popular and was inlaid upon countless sword-blades after perhaps about 1250. It is difficult to draw a line between religious and trademarks: hearts, for instance, whether on their own or within a circle might be either; but where we find a helm, or a shield, or a sword (there is a sword inlaid in the blade of the Type XIII war-sword in the Guildhall Museum, Oakeshott, 1960, pl.7c), or a bull's head (on a sword c. 1300 in Copenhagen), or of course the famous 'Wolf' which is first found on thirteenth-century blades. A mark which can easily be mistaken for the 'Wolf' of Passau is a unicorn; since both wolf and unicorn are only very summarily sketched with a few inlaid strokes, it needs 'the eye of faith' to distinguish an animal at all; the examples of the unicorns which Oakeshott saw on various blades looked exactly the same as the wolves, except that they have a long straight stroke sticking out in front (Oakeshott, 1960, p.223, fig.105b"). Fine condition. Very rare.

Late 17th century AD. A long Western two-handed executioner sword of German making; the pear-shaped pommel is mounted on the original still preserved wooden grip; the cross guard is straight, ending with straight quillons; the double edged blade is broad and flat, without fullers, having a round tip and a three holes for the blood at the point; the sword is marked on both sides: on one side there is a circle inside which a Christian monogram (chi-ro) cross is inscribed, supported by a short staff; on the other side there is the image of a gallows, both inlaid in copper. See Fischer, Kunst und Antiquitätenauktion antike Waffen und militaria, Montag, 30. August, bis Montag, 6. September 2004, Luzern, 2004; Ni?oi A., Posea R., 'Spade de execu?ie ale ora?uluj Bra?ov ?n perioada medievalã ?i modernã', in Rela?ii Interetnice în Transilvania, Militaria Mediaevalia în Europa centralã si de sud-est, Sibiu, 2018, pp.113-126. 2 kg, 1.12cm (44 1/4"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; believed originally from Liege, Belgium; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. This Sword of Justice was employed for capital executions. The executioner sword was a symbolic and ‘facilitator’ of judicial law. Many courtrooms displayed executioner swords on their walls. Specimens similar to the sword here published are well known in public and private European collections (Fischer, 2004, cat.99 and 126"). The marks impressed on the blade are identical to a sample published by Fischer in the auction of 2004, having, like our specimen, a wide, flat, double-edged blade, marks, brass-plated wheel and gallows, with the adding of engraved scrolls and floral decor. A further similar model survives in the Medieval Crime Museum (Mittelalterliches Kriminalmuseum) in Germany. Such swords come at the tail end of the period in which swords were used in Europe for executions (a period from the 16th century to the 1720s. They feature similar characteristics: a long, heavy blade that ended not in a point but with a distinctive flat edge. The blades of the executioner’s swords were often decorated, and while in some cases the sword would be inscribed with the executioner’s name in other cases were put inscriptions like I spare no one – a brutal message for criminals (or poor victims or the state's reason) facing this sword’s edge. Sometimes the messages were more merciful, like in the case of a blade recently published by the Museum of the Artifacts, made in Germany in about 1600 AD: the inscriptions is saying: when I raise this sword, so i wish that this poor sinner will receive eternal life. The blades of executioner's swords were often decorated also with symbolic designs, showing instruments of execution or torture, or the Crucifixion of Christ (like in our specimen) combined with the moralistic inscriptions over mentioned. When no longer used for executions, an executioner's sword sometimes continued to be used as a ceremonial sword of justice, a symbol of judicial power. Recently, important samples of executioner's swords from Transilvania have been published by Anca Nitoi and Rozalinda Posea. Along with Sibiu and Cluj, the city of Brasov holds spectacular items with regards to late and early modern time executioner's swords. The three swords published by the Rumenian archaelogists ranges from the 16th to the XVIII century. The first two had a hilt very similar to the specimen here represented, and are considered by the authors as belonging to the Oakeshott sub-type XVIIIb of his sword's classification. Interesting are the three inscriptions on the blade of one of the XVI century sword: JESVS DIR LEB ICH, JESVS DIR STIRB ICH, DEIN BIN ICH TOT UND LEBENDING (Jesus for You I live; Jesus for You I die; I am Yours in life and in death"). The inscription confirms that in any case a sense of mercy was given to the condemned, letting him to repent of his sins until the end, even with a sort of blessing left on the blade destined to put end to his life. Most probably our specimen is coming from a palace as it is in such excellent condition. Executioners’ swords were more common in continental Europe from the 1400s, particularly Germany, with England still preferring the axe. The sword hilt was normally of conventional cruciform shape with a large counter-balancing pommel. It was very well constructed, with high-quality steel used for the manufacture of the blade. The blade edge was extremely sharp and it was a requirement of the executioner to keep it well honed so that the head of the victim could be severed in one mighty blow. Blades were broad and flat backed, with a rounded tip. These swords were intended for two-handed use, but were lacking a point, so that their overall length was typically that of a single-handed sword (ca. 80–90 cm (31–35 in)"). The quillons were quite short, and mainly straight, and the pommel was often pear-shaped (like in our specimen) or faceted. The sword was designed for cutting rather than thrusting, so a pointed tip (as in the case of military blades) was unnecessary. Differently from the arming sword and the double handed bastard sword of the late Renaissance and Baroque Age the tool of the executioner's sword was not designed for combat, instead being intended for the quick death – usually through decapitation – of the condemned. This weapon would not need to be combat worthy, but would still be capable of fulfilling its intended purpose. By the early 1700s swords were no longer used in Europe for executions, but they still functioned as symbols of power. However, the last executions by sword in Europe were carried out in Switzerland in 1867 and 1868, when Niklaus Emmenegger in Lucerne and Héli Freymond in Moudon were beheaded for murder. Swords are still used to carry out executions in Saudi Arabia. Fine condition. Very rare.

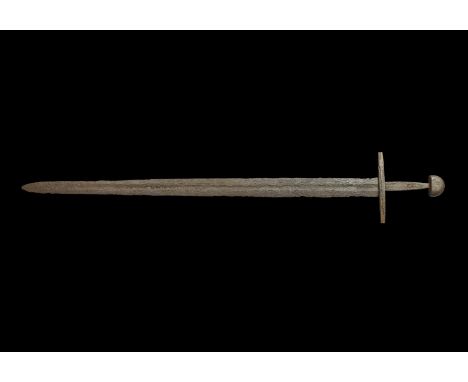

10th-12th century AD. A Viking or Norman Sword with a fine double-edged tapered blade, still retaining well-defined cutting edges and fullers, although the latter being extremely shallow with vague boundaries; traces of employment in fight are visible on the sides and on the point; the blade of the weapon is pattern-welded; the hilt is in excellent condition, comprising of a flat tapering tang and the typical, lower, thicker and shorter pommel of 'tea-cosy' form, with the lower and wider guard reaching a considerable length; overall, the hilt is plain, carrying no form of decoration, and yet, when all of its components are considered as a whole, the effect produced is one of harmony, balance and quality; the sturdy tang provides tremendous strength to the hilt of this long-bladed weapon. See Petersen, J., De Norske Vikingsverd, Oslo, 1919; Oakeshott, E. Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991; Gravett, C., Medieval Norman Knight, 950-1204 AD, London, 1993; Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002. 853 grams, 92cm (36 1/4"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. This sword belongs to the known type X of Petersen (Petersen,1919, pp.158ff) and finds good parallels in various similar Viking age specimens. A very similar sword, with a similar hilt, is the Hagerbakken sword (s. Petersen, 1919, fig.124"). A second parallel can be represented by the sword kept in the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, at the Downing College, Cambridge, found in the River Great Ouse and dating from c. 950-1000, an example is in excellent condition except for the large hole below the cross-guard, which presents iron inlays with inscriptions. Another good parallel is the sword from Vammala (Peirce, 2002, p.132), although the pommel of this latter is tiny than in our sword and yet most precisely formed, being of a 'tea-cosy' type in transition to a 'Brazil nut'. These are types of swords having simpler kind of ornamentation, and they occur in greater numbers, giving on the whole a domestic impression, though it is difficult to fully understand their origin of production, i.e. if local or imported in Viking countries. Contrary to types like B, C and F, these types belong to the late Viking Age, and they also represent a later period than type M, almost simultaneous with type Q, but preceding the last familiar type, type Æ. Our sword belongs to later and most usual of the two variants of type X, with its lower, thicker and shorter pommel and a lower and wider lower guard that at times can reach a considerable length, but that can also be quite short as in type M for example. The cross-section of the hilt is here evenly wide, with rounded ends, and not cut sharply across, which is otherwise usual with type M. The first group has upper hilts [pommels] that can reach a length of 7.8 cm. and a height of 5.1 cm. The second group has pommels with a length between 5.0 cm and 6.5 cm., the height is from 2.7 cm - 3.5 cm. The lower guard varies in length between 10.7 cm to an entire 17.7 cm. The height in the first group is up to 2.0 cm. and in the second group from 0.7 cm to 1.4 cm. At the time when Petersen wrote his huge work he knew not less than 49 specimens of this type, of which this later variant was the most usual. With respect to the actual typological development of the type, it is evident that the taller, slimmer pommels were the early ones, and the small, thick, blunt pommels were the later ones (see for instance the swords of type XI,1-2, Oakeshott,1991, p.54), with the smaller, thicker pommels following the longer lower guards. In particular we shall mention here the sword C 12217 from Sandeherred (Petersen, 1919, fig.129), where the transition to medieval swords has already begun. In this last sword the underside of the already begun to become convex. Blade and handle are very well preserved. Most probably our specimen is coming from a river or a battlefield. The piece is in excellent condition. According to the actual archaeological evidence, type X embraces a very extensive time period. It has been a usual statement given by archaeologists when they speak of this type, that generally it belonged to the end of the Viking Age. One has evidently thought in terms of the medieval forms, with the long straight guards and a more or less rounded pommel. It is however, not that simple, according to Petersen. It is evident that individual swords of the X-type belong among the latest of our swords from the Viking Age, i.e. the 11th and the 12th century. But it is equally evident that the first forms of this type appeared already in the first half of the 10th century. Equally certain, however, is that this type lasted until the very end of the Viking Age. Petersen pointed first one find as mentioned from Nomedal in Hyllestad, and also the over mentioned find c. 1292 from Hagerbakken, V. Toten, where the sword has that long lower guard and represents the best parallel for our sword. These are without doubt at least from the end of the 10th century, most likely even from the beginning of the 11th century. Also another find St. 2589 from Vestly, Lye, Stav. with axe blades of a marked M type, must belong to the last part of the Viking Age. With regards to the additional finds we must believe that these are thought to complete the remaining parts of the 10th century. Based on the available material it is difficult to determine with any more specificity, but we should observe that some swords represented on the Bayeux tapestry and employed by the warriors there represented show such typology (Sword of Harold, Gravett, 1993, p.12"). The swords with tea-cosy pommels were popular among the early Normans and late Vikings (Gravett, 1993, p.5, sample from Wallace collection in British Museum; s. also pp.13-14; pl.A,F"). Fine condition. Very rare.