We found 400965 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 400965 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

400965 item(s)/page

§ George Kennethson (British 1910-1994) Wave Form, circa 1950s-60s Clipsham stoneDimensions:43cm high, 30.5cm wide, 20cm deep (17in high, 12in wide, 7 3/4in deep)Provenance:ProvenanceThe Estate of the Artist.Note: LiteratureCork, Richard. The Sculpture of George Kennethson, Redfern Gallery, London, 2014, p. 20 illustrated in the background of a photograph of the artist's studio. George Kennethson (or Arthur Mackenzie as he was, Kennethson being the name he adopted in the early 1970s in order to separate his artistic practice from his role as the art master at Oundle School) met Eileen Guthrie in 1931 at the Royal Academy Schools in London. Intriguingly both were painting students, although in George’s case, the teaching at the still very academic Academy mainly had the effect of turning him into a sculptor, something he was already considering by his final year when the pair of them met [although one of his sons recalls Kennethson generously saying that the reason he became a sculptor was that Eileen was by far the better painter].George had come from a cultured, literary family. Eileen’s father and grandfather were architects and her mother was an accomplished pianist, who had studied at the Royal College of Music [Eileen herself had been taught piano by Gustav Holst when she was young]. And so, like many of their circle, Eileen and George were left-wing in their politics, interested in all things avant-garde in art, music and literature, and looked to Paris for inspiration. As young artists they both revered Cezanne. On their first trip together to the French capital, George tracked down the work of sculptors Maillol, Zadkine and Brancusi. And Eileen no doubt sought out the work of Bonnard, whose influence, both in composition and technique, can be traced in her work. They returned, in 1937, where they saw Picasso’s recently completed Guernica, which moved them both, artistically and politically. Like many artists of their generation, their lives and careers were profoundly affected by the Second World War. The Kennethsons were committed pacifists. A year before war broke out, they had moved to the quiet Berkshire village of Uffington, watched over by its ancient, curiously abstract White Horse, cut into the chalk of the nearby Downs, and so in away had already withdrawn from the political storm of the late 30s. The local villagers had no issues with the Kennethsons’ avowed pacifism: they were artists, after all, so they expected them to be different. Whilst they passed the war in rural seclusion, conflict does seep into Kennethson’s sculpture, such as sculptures of travellers, with staffs and backpacks, or men carrying mattresses down to the local forge – images glimpsed out of the studio window, but now transformed into a moving response to the refugees that war inevitably creates. The couple took in both evacuees from the Blitz and the occasional European refugee (and much later in the 1980s, Kennethson returned to this theme as a response to the migrations forced by famine in Ethiopia). But more than this, the War and its aftermath led to little opportunity for artists to sell their work and therefore live by their art – something that was particularly acute for the Kennethsons, who by the late 1940s had five young boys to feed. Art historians have often been critical of British artists ‘retreating’ into teaching or commercial work, whilst their counterparts in America were splashing newly made paint across acres of pristine canvas and changing the direction of modern art forever, and yet this ignores the pressures on British artists, facing a public that was already relatively indifferent to modern art already and which now was broke.It was at this point that Eileen turned her hand to making prints for textiles. She did so with incredible success – artistically at least, as there was almost as little money for interiors and design in post-war Britain as there was for at. Eileen did, however, sell her ‘Flockhart Fabrics’ range – named after her Scottish grandfather - at Primavera, a leading interiors shop on Sloane Street, as well as to family and friends. Their neighbour in Uffington, John Betjeman, also helped them to find stockists, and Eileen’s twin sister Joan would open her London flat to showcase the designs. Lucienne Day, too, introduced Eileen to Amersham Prints, contractors to the government, and her design Bird and Basket was used in 1954 to furnish the Morag Mhor, the first all-aluminium yacht in the country.George lent a hand too, on the production side, contributing to designs, working on the lino-blocks and silkscreens and helping Eileen with the considerable manual work of printing the fabrics by hand. The prints are deceptively simple, strong and sculptural, whilst retaining the required elegance and beauty. The line that one sees in her gouaches and oils find an easy home amongst the repeats of fabric design and motifs that infuse George’s sculpture – birds, leaves, architectonic flower forms – are abstracted from her landscape painting.The family moved to Oundle in 1954, to a house with a large former malting attached, which made for good, if draughty, studios. George would have been surrounded by Eileen’s fabrics – at the long settle by the kitchen table or on one of the armchairs where he would read and draw- before heading out to his studio to carve equally simple forms, with soft curves and sharp edges, into stone and alabaster, so perhaps Eileen’s influence on George’s work shouldn’t be under-estimated. Meeting her late in her life – a decade after George’s death – she would walk amongst the sculptures, laid out on plinths in a cavernous Victorian former malting attached to their house, and place her hands intuitively on every undercut and turn (the wearing of rings was strictly forbidden!). George resolutely worked alone – no assistants, no power tools, only mallets and chisels and cassettes of classical music and operatic arias for company – but the confluence between their work speaks to a shared vision. We are delighted to include in this selection a painting by Eileen alongside a drawing of George’s, both made at their beloved Isle of Purbeck, where they had holidayed (and found inspiration, in the fields, quarries and shore) every year since the late 1930s. Seen side by side, these works could almost be by the same hand. George’s drawings, mainly of the rock formations of the coast that were the source of his material, whilst studies in sculptural form, have a painter’s confident flow: equally, Eileen’s paintings, whilst more concerned with the wider landscape, have a certain sculptural feel to their construction, even though, in the end, they concern themselves more with colour and abstract form, in the manner of Ivon Hitchens or Patrick Heron, both of whom she admired. The last few years have seen something of a revival in interest in George Kennethson’s work. After all, this is an artist whose work sits very comfortably – and beautifully – in Britain’s best small museum, Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, alongside Constantin Brancusi and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. There are now two monographs on the artist, the most recent written by the eminent critic Richard Cork. Eileen Guthrie’s work, on the other hand, still remains something of a secret, her last public exhibitions being held almost 40 years ago now. We hope that this brief glimpse will be the beginning of her revival, as well as a testament an artistic partnership that was very much of its time, yet resonates with beauty today.

§ George Kennethson (British 1910-1994) Girl's Back with Curled Hair - Study for Sculpture, circa 1960 ink and wash on paperDimensions:16cm x 12.5cm (6 3/8in x 4 7/8in)Provenance:ProvenanceThe Estate of the Artist.Note: LiteratureHucker, Simon. George Kennethson: A Modernist Rediscovered. London: Merrell Publishers Limited, 2004, p.14, illustrated. George Kennethson (or Arthur Mackenzie as he was, Kennethson being the name he adopted in the early 1970s in order to separate his artistic practice from his role as the art master at Oundle School) met Eileen Guthrie in 1931 at the Royal Academy Schools in London. Intriguingly both were painting students, although in George’s case, the teaching at the still very academic Academy mainly had the effect of turning him into a sculptor, something he was already considering by his final year when the pair of them met [although one of his sons recalls Kennethson generously saying that the reason he became a sculptor was that Eileen was by far the better painter].George had come from a cultured, literary family. Eileen’s father and grandfather were architects and her mother was an accomplished pianist, who had studied at the Royal College of Music [Eileen herself had been taught piano by Gustav Holst when she was young]. And so, like many of their circle, Eileen and George were left-wing in their politics, interested in all things avant-garde in art, music and literature, and looked to Paris for inspiration. As young artists they both revered Cezanne. On their first trip together to the French capital, George tracked down the work of sculptors Maillol, Zadkine and Brancusi. And Eileen no doubt sought out the work of Bonnard, whose influence, both in composition and technique, can be traced in her work. They returned, in 1937, where they saw Picasso’s recently completed Guernica, which moved them both, artistically and politically. Like many artists of their generation, their lives and careers were profoundly affected by the Second World War. The Kennethsons were committed pacifists. A year before war broke out, they had moved to the quiet Berkshire village of Uffington, watched over by its ancient, curiously abstract White Horse, cut into the chalk of the nearby Downs, and so in away had already withdrawn from the political storm of the late 30s. The local villagers had no issues with the Kennethsons’ avowed pacifism: they were artists, after all, so they expected them to be different. Whilst they passed the war in rural seclusion, conflict does seep into Kennethson’s sculpture, such as sculptures of travellers, with staffs and backpacks, or men carrying mattresses down to the local forge – images glimpsed out of the studio window, but now transformed into a moving response to the refugees that war inevitably creates. The couple took in both evacuees from the Blitz and the occasional European refugee (and much later in the 1980s, Kennethson returned to this theme as a response to the migrations forced by famine in Ethiopia). But more than this, the War and its aftermath led to little opportunity for artists to sell their work and therefore live by their art – something that was particularly acute for the Kennethsons, who by the late 1940s had five young boys to feed. Art historians have often been critical of British artists ‘retreating’ into teaching or commercial work, whilst their counterparts in America were splashing newly made paint across acres of pristine canvas and changing the direction of modern art forever, and yet this ignores the pressures on British artists, facing a public that was already relatively indifferent to modern art already and which now was broke.It was at this point that Eileen turned her hand to making prints for textiles. She did so with incredible success – artistically at least, as there was almost as little money for interiors and design in post-war Britain as there was for at. Eileen did, however, sell her ‘Flockhart Fabrics’ range – named after her Scottish grandfather - at Primavera, a leading interiors shop on Sloane Street, as well as to family and friends. Their neighbour in Uffington, John Betjeman, also helped them to find stockists, and Eileen’s twin sister Joan would open her London flat to showcase the designs. Lucienne Day, too, introduced Eileen to Amersham Prints, contractors to the government, and her design Bird and Basket was used in 1954 to furnish the Morag Mhor, the first all-aluminium yacht in the country.George lent a hand too, on the production side, contributing to designs, working on the lino-blocks and silkscreens and helping Eileen with the considerable manual work of printing the fabrics by hand. The prints are deceptively simple, strong and sculptural, whilst retaining the required elegance and beauty. The line that one sees in her gouaches and oils find an easy home amongst the repeats of fabric design and motifs that infuse George’s sculpture – birds, leaves, architectonic flower forms – are abstracted from her landscape painting.The family moved to Oundle in 1954, to a house with a large former malting attached, which made for good, if draughty, studios. George would have been surrounded by Eileen’s fabrics – at the long settle by the kitchen table or on one of the armchairs where he would read and draw- before heading out to his studio to carve equally simple forms, with soft curves and sharp edges, into stone and alabaster, so perhaps Eileen’s influence on George’s work shouldn’t be under-estimated. Meeting her late in her life – a decade after George’s death – she would walk amongst the sculptures, laid out on plinths in a cavernous Victorian former malting attached to their house, and place her hands intuitively on every undercut and turn (the wearing of rings was strictly forbidden!). George resolutely worked alone – no assistants, no power tools, only mallets and chisels and cassettes of classical music and operatic arias for company – but the confluence between their work speaks to a shared vision. We are delighted to include in this selection a painting by Eileen alongside a drawing of George’s, both made at their beloved Isle of Purbeck, where they had holidayed (and found inspiration, in the fields, quarries and shore) every year since the late 1930s. Seen side by side, these works could almost be by the same hand. George’s drawings, mainly of the rock formations of the coast that were the source of his material, whilst studies in sculptural form, have a painter’s confident flow: equally, Eileen’s paintings, whilst more concerned with the wider landscape, have a certain sculptural feel to their construction, even though, in the end, they concern themselves more with colour and abstract form, in the manner of Ivon Hitchens or Patrick Heron, both of whom she admired. The last few years have seen something of a revival in interest in George Kennethson’s work. After all, this is an artist whose work sits very comfortably – and beautifully – in Britain’s best small museum, Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, alongside Constantin Brancusi and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. There are now two monographs on the artist, the most recent written by the eminent critic Richard Cork. Eileen Guthrie’s work, on the other hand, still remains something of a secret, her last public exhibitions being held almost 40 years ago now. We hope that this brief glimpse will be the beginning of her revival, as well as a testament an artistic partnership that was very much of its time, yet resonates with beauty today.

§ George Kennethson (British 1910-1994) Waves initialled (lower right), pencil, ink and wash on blue paperDimensions:18cm x 22cm (7 1/8in x 8 5/8in)Provenance:ProvenanceThe Estate of the Artist.Note: George Kennethson (or Arthur Mackenzie as he was, Kennethson being the name he adopted in the early 1970s in order to separate his artistic practice from his role as the art master at Oundle School) met Eileen Guthrie in 1931 at the Royal Academy Schools in London. Intriguingly both were painting students, although in George’s case, the teaching at the still very academic Academy mainly had the effect of turning him into a sculptor, something he was already considering by his final year when the pair of them met [although one of his sons recalls Kennethson generously saying that the reason he became a sculptor was that Eileen was by far the better painter].George had come from a cultured, literary family. Eileen’s father and grandfather were architects and her mother was an accomplished pianist, who had studied at the Royal College of Music [Eileen herself had been taught piano by Gustav Holst when she was young]. And so, like many of their circle, Eileen and George were left-wing in their politics, interested in all things avant-garde in art, music and literature, and looked to Paris for inspiration. As young artists they both revered Cezanne. On their first trip together to the French capital, George tracked down the work of sculptors Maillol, Zadkine and Brancusi. And Eileen no doubt sought out the work of Bonnard, whose influence, both in composition and technique, can be traced in her work. They returned, in 1937, where they saw Picasso’s recently completed Guernica, which moved them both, artistically and politically. Like many artists of their generation, their lives and careers were profoundly affected by the Second World War. The Kennethsons were committed pacifists. A year before war broke out, they had moved to the quiet Berkshire village of Uffington, watched over by its ancient, curiously abstract White Horse, cut into the chalk of the nearby Downs, and so in away had already withdrawn from the political storm of the late 30s. The local villagers had no issues with the Kennethsons’ avowed pacifism: they were artists, after all, so they expected them to be different. Whilst they passed the war in rural seclusion, conflict does seep into Kennethson’s sculpture, such as sculptures of travellers, with staffs and backpacks, or men carrying mattresses down to the local forge – images glimpsed out of the studio window, but now transformed into a moving response to the refugees that war inevitably creates. The couple took in both evacuees from the Blitz and the occasional European refugee (and much later in the 1980s, Kennethson returned to this theme as a response to the migrations forced by famine in Ethiopia). But more than this, the War and its aftermath led to little opportunity for artists to sell their work and therefore live by their art – something that was particularly acute for the Kennethsons, who by the late 1940s had five young boys to feed. Art historians have often been critical of British artists ‘retreating’ into teaching or commercial work, whilst their counterparts in America were splashing newly made paint across acres of pristine canvas and changing the direction of modern art forever, and yet this ignores the pressures on British artists, facing a public that was already relatively indifferent to modern art already and which now was broke.It was at this point that Eileen turned her hand to making prints for textiles. She did so with incredible success – artistically at least, as there was almost as little money for interiors and design in post-war Britain as there was for at. Eileen did, however, sell her ‘Flockhart Fabrics’ range – named after her Scottish grandfather - at Primavera, a leading interiors shop on Sloane Street, as well as to family and friends. Their neighbour in Uffington, John Betjeman, also helped them to find stockists, and Eileen’s twin sister Joan would open her London flat to showcase the designs. Lucienne Day, too, introduced Eileen to Amersham Prints, contractors to the government, and her design Bird and Basket was used in 1954 to furnish the Morag Mhor, the first all-aluminium yacht in the country.George lent a hand too, on the production side, contributing to designs, working on the lino-blocks and silkscreens and helping Eileen with the considerable manual work of printing the fabrics by hand. The prints are deceptively simple, strong and sculptural, whilst retaining the required elegance and beauty. The line that one sees in her gouaches and oils find an easy home amongst the repeats of fabric design and motifs that infuse George’s sculpture – birds, leaves, architectonic flower forms – are abstracted from her landscape painting.The family moved to Oundle in 1954, to a house with a large former malting attached, which made for good, if draughty, studios. George would have been surrounded by Eileen’s fabrics – at the long settle by the kitchen table or on one of the armchairs where he would read and draw- before heading out to his studio to carve equally simple forms, with soft curves and sharp edges, into stone and alabaster, so perhaps Eileen’s influence on George’s work shouldn’t be under-estimated. Meeting her late in her life – a decade after George’s death – she would walk amongst the sculptures, laid out on plinths in a cavernous Victorian former malting attached to their house, and place her hands intuitively on every undercut and turn (the wearing of rings was strictly forbidden!). George resolutely worked alone – no assistants, no power tools, only mallets and chisels and cassettes of classical music and operatic arias for company – but the confluence between their work speaks to a shared vision. We are delighted to include in this selection a painting by Eileen alongside a drawing of George’s, both made at their beloved Isle of Purbeck, where they had holidayed (and found inspiration, in the fields, quarries and shore) every year since the late 1930s. Seen side by side, these works could almost be by the same hand. George’s drawings, mainly of the rock formations of the coast that were the source of his material, whilst studies in sculptural form, have a painter’s confident flow: equally, Eileen’s paintings, whilst more concerned with the wider landscape, have a certain sculptural feel to their construction, even though, in the end, they concern themselves more with colour and abstract form, in the manner of Ivon Hitchens or Patrick Heron, both of whom she admired. The last few years have seen something of a revival in interest in George Kennethson’s work. After all, this is an artist whose work sits very comfortably – and beautifully – in Britain’s best small museum, Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, alongside Constantin Brancusi and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. There are now two monographs on the artist, the most recent written by the eminent critic Richard Cork. Eileen Guthrie’s work, on the other hand, still remains something of a secret, her last public exhibitions being held almost 40 years ago now. We hope that this brief glimpse will be the beginning of her revival, as well as a testament an artistic partnership that was very much of its time, yet resonates with beauty today.

§ George Kennethson (British 1910-1994) Father and Child, 1960s English alabasterDimensions:45.7cm high, 33cm wide, 25.5cm deep (18in high, 13in wide, 10in deep)Provenance:ProvenanceThe Estate of the Artist.Note: George Kennethson (or Arthur Mackenzie as he was, Kennethson being the name he adopted in the early 1970s in order to separate his artistic practice from his role as the art master at Oundle School) met Eileen Guthrie in 1931 at the Royal Academy Schools in London. Intriguingly both were painting students, although in George’s case, the teaching at the still very academic Academy mainly had the effect of turning him into a sculptor, something he was already considering by his final year when the pair of them met [although one of his sons recalls Kennethson generously saying that the reason he became a sculptor was that Eileen was by far the better painter].George had come from a cultured, literary family. Eileen’s father and grandfather were architects and her mother was an accomplished pianist, who had studied at the Royal College of Music [Eileen herself had been taught piano by Gustav Holst when she was young]. And so, like many of their circle, Eileen and George were left-wing in their politics, interested in all things avant-garde in art, music and literature, and looked to Paris for inspiration. As young artists they both revered Cezanne. On their first trip together to the French capital, George tracked down the work of sculptors Maillol, Zadkine and Brancusi. And Eileen no doubt sought out the work of Bonnard, whose influence, both in composition and technique, can be traced in her work. They returned, in 1937, where they saw Picasso’s recently completed Guernica, which moved them both, artistically and politically. Like many artists of their generation, their lives and careers were profoundly affected by the Second World War. The Kennethsons were committed pacifists. A year before war broke out, they had moved to the quiet Berkshire village of Uffington, watched over by its ancient, curiously abstract White Horse, cut into the chalk of the nearby Downs, and so in away had already withdrawn from the political storm of the late 30s. The local villagers had no issues with the Kennethsons’ avowed pacifism: they were artists, after all, so they expected them to be different. Whilst they passed the war in rural seclusion, conflict does seep into Kennethson’s sculpture, such as sculptures of travellers, with staffs and backpacks, or men carrying mattresses down to the local forge – images glimpsed out of the studio window, but now transformed into a moving response to the refugees that war inevitably creates. The couple took in both evacuees from the Blitz and the occasional European refugee (and much later in the 1980s, Kennethson returned to this theme as a response to the migrations forced by famine in Ethiopia). But more than this, the War and its aftermath led to little opportunity for artists to sell their work and therefore live by their art – something that was particularly acute for the Kennethsons, who by the late 1940s had five young boys to feed. Art historians have often been critical of British artists ‘retreating’ into teaching or commercial work, whilst their counterparts in America were splashing newly made paint across acres of pristine canvas and changing the direction of modern art forever, and yet this ignores the pressures on British artists, facing a public that was already relatively indifferent to modern art already and which now was broke.It was at this point that Eileen turned her hand to making prints for textiles. She did so with incredible success – artistically at least, as there was almost as little money for interiors and design in post-war Britain as there was for at. Eileen did, however, sell her ‘Flockhart Fabrics’ range – named after her Scottish grandfather - at Primavera, a leading interiors shop on Sloane Street, as well as to family and friends. Their neighbour in Uffington, John Betjeman, also helped them to find stockists, and Eileen’s twin sister Joan would open her London flat to showcase the designs. Lucienne Day, too, introduced Eileen to Amersham Prints, contractors to the government, and her design Bird and Basket was used in 1954 to furnish the Morag Mhor, the first all-aluminium yacht in the country.George lent a hand too, on the production side, contributing to designs, working on the lino-blocks and silkscreens and helping Eileen with the considerable manual work of printing the fabrics by hand. The prints are deceptively simple, strong and sculptural, whilst retaining the required elegance and beauty. The line that one sees in her gouaches and oils find an easy home amongst the repeats of fabric design and motifs that infuse George’s sculpture – birds, leaves, architectonic flower forms – are abstracted from her landscape painting.The family moved to Oundle in 1954, to a house with a large former malting attached, which made for good, if draughty, studios. George would have been surrounded by Eileen’s fabrics – at the long settle by the kitchen table or on one of the armchairs where he would read and draw- before heading out to his studio to carve equally simple forms, with soft curves and sharp edges, into stone and alabaster, so perhaps Eileen’s influence on George’s work shouldn’t be under-estimated. Meeting her late in her life – a decade after George’s death – she would walk amongst the sculptures, laid out on plinths in a cavernous Victorian former malting attached to their house, and place her hands intuitively on every undercut and turn (the wearing of rings was strictly forbidden!). George resolutely worked alone – no assistants, no power tools, only mallets and chisels and cassettes of classical music and operatic arias for company – but the confluence between their work speaks to a shared vision. We are delighted to include in this selection a painting by Eileen alongside a drawing of George’s, both made at their beloved Isle of Purbeck, where they had holidayed (and found inspiration, in the fields, quarries and shore) every year since the late 1930s. Seen side by side, these works could almost be by the same hand. George’s drawings, mainly of the rock formations of the coast that were the source of his material, whilst studies in sculptural form, have a painter’s confident flow: equally, Eileen’s paintings, whilst more concerned with the wider landscape, have a certain sculptural feel to their construction, even though, in the end, they concern themselves more with colour and abstract form, in the manner of Ivon Hitchens or Patrick Heron, both of whom she admired. The last few years have seen something of a revival in interest in George Kennethson’s work. After all, this is an artist whose work sits very comfortably – and beautifully – in Britain’s best small museum, Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, alongside Constantin Brancusi and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. There are now two monographs on the artist, the most recent written by the eminent critic Richard Cork. Eileen Guthrie’s work, on the other hand, still remains something of a secret, her last public exhibitions being held almost 40 years ago now. We hope that this brief glimpse will be the beginning of her revival, as well as a testament an artistic partnership that was very much of its time, yet resonates with beauty today.

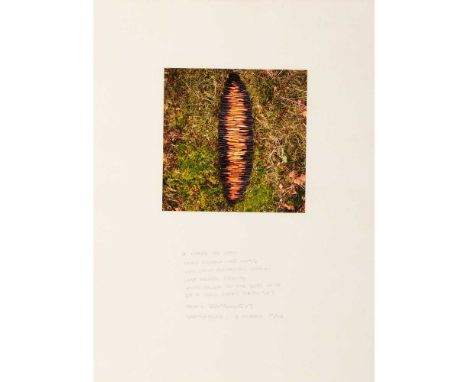

§ Andy Goldsworthy (British 1956-) Series of Seven Works, 1987-94 each inscribed, signed and dated in pencil, 6 c-prints and one work with traces of snow and dirt on paper, comprising:STONEWOOD SCAUR / ANDY GOLDSWORTHY / AUTUMN '87 and inscribed with poem, 20cm x 26cm (framed 72.5cm x 52.5cm);Slate, midday / collected locally / left over from roof repairs / lived under by many people / protecting the oak – burnt at its base – limbs sawn off / a partnership / STONEWOOD SCAUR / ANDY GOLDSWORTHY / SUMMER 88, each image 19cm x 12.5cm (framed 72cm x 52.5cm);The wall / Stonework by Joe Smith of Crocket**** / Winter 88/89 / STONEWOOD / ANDY GOLDSWORTHY, 25cm x 16.5cm (framed 72.5cm x 52.5cm);A MONTH OF RAIN / DEEP GREEN WET MOSS / UPROOTED BROKEN STACKS / LAST YEARS GROWTH / MOSS COLOUR IN THE SOFT LIGHT / OF A DULL GREY HEAVY SKY / ANDY GOLDSWORTHY / STONEWOOD/ 5 MARCH 1990, 18.5cm x 19cm (framed 72cm x 52cm);SNOW AND EARTH / STONEWOOD / ANDY GOLDSWORTHY 1991, traces of snow and dirt on paper, 51cm x 38cm (framed 72.5cm x 52.5cm);THE WALL / SUMMER 1993 / ANDY GOLDSWORTHY, 19cm x 23.5cm (framed 68cm x 53cm);TREE/ STICK / SNOW / STONEWOOD / ANDY GOLDSWORTHY 10 JAN 94, 23.5cm x 16cm (framed 68cm x 53cm)Dimensions:variable dimensionsProvenance:ProvenancePrivate Collection, Scotland. In 1987 the present owners' family gave financial support to Andy Goldsworthy's Stone Wood Plot Fund. In return the Artist supplied seven works (in editions of no more than 10) between 1987 and 1994.

§ Breon O'Casey (British 1928-2011) Boat, 1999 signed and dated in pencil in margin (lower right), numbered 11/15 (lower left), linocut on paperDimensions:45cm x 44cm (17 3/4in x 17 3/8in)Provenance:ProvenancePrivate Collection, Scotland.Note: ‘Breon O’Casey is a man for all seasons. He thinks and feels with his hands and moves with apparent ease from two-dimensional to three-dimensional activities, from one medium to another, without losing the artistic integrity of his intent. Breon O’Casey’s sensitive observations of life, art and nature inform his rich personal, visual language and beautifully balanced prose. His respect for his immediate environment and for tradition have enabled him to move forward with a confident, quiet ease, creating a refreshingly honest approach to art. He is an artist who is prepared to wait for the right shape, for the right brushstroke or the perfectly chosen word to express his meaning’. (Peter Murray (1)) Breon O’Casey was a true polymath and was possibly unique in the combination of skills he possessed over so many mediums in a single career. He was a painter, printmaker, weaver, sculptor and jewellery maker and it is hard to think of any other contemporary artist and maker who was so broadly talented. Son of the playwright Sean O’Casey (1880-1964), Breon spent most of his career in Cornwall, where he was closely associated with many of the painters, potters and sculptors of the St Ives movement. He arrived in the coastal town in the 1959 and served artistic apprenticeships under sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Denis Mitchell, and was friends with leading artists such as Peter Lanyon, John Wells and Tony O’Malley. In 1999 O’Casey recalled: ‘One day, watching television, some time in the late fifties, I saw a film about Alfred Wallis…the film incidentally showed St Ives and the studios of the artists living there. I realised it was the place for me. I owned a small orange Ford van. I packed the van and went. St Ives! In those days it was still a working fishing port, with tourism and artists tolerated, but kindly tolerated. Coming from Torquay, where I had felt like a rhinoceros walking along the streets, the relief of mingling with other crazy artists was enormous…I felt secure and there was a sort of electricity in the air.’ (2) O’Casey’s abstract style was poetic and focussed on discovering the simplicity of objects and forms. For him there was ‘nothing new under the sun, but an infinity of arrangements’ and when asked about objects that captivated him it was ‘not the wood, not the tree, but the leaf; not the distant view, but the hedge; not the mountain, but the stone’. He would return to geometric motifs and natural forms again and again throughout his career and considered himself a ‘traditional innovator’, fascinated by ancient, primitive and non-western art, but imbuing it with his own poetic sensibilities and discoveries through all the creative channels he explored. Although often overshadowed by his St Ives contemporaries, O’Casey’s legacy, talents and unique skills are now being reassessed, and greater importance given to his accomplishments beyond narrow and interlocked art circles. We are delighted to bring this collection of his work together to showcase many of the aspects of O’Casey’s prodigious artistic output, and to celebrate his significance as a true renaissance figure of British 20th-century art and craft. 1 / Peter Murray quoted in Sarah Coulson and Sophie Bowness, Breon O’Casey: An Anthology of his Writings, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, 2005, p.32 / Breon O’Casey quoted in Brian Fallon and Breon O’Casey, Breon O’Casey¸ Scolar Press, Aldershot, 1999, p.48.

§ Breon O'Casey (British 1928-2011) Necklace unmarked, white metalDimensions:Length: 59cm (23 1/4in)Provenance:ProvenancePrivate Collection, Scotland.Note: ‘Breon O’Casey is a man for all seasons. He thinks and feels with his hands and moves with apparent ease from two-dimensional to three-dimensional activities, from one medium to another, without losing the artistic integrity of his intent. Breon O’Casey’s sensitive observations of life, art and nature inform his rich personal, visual language and beautifully balanced prose. His respect for his immediate environment and for tradition have enabled him to move forward with a confident, quiet ease, creating a refreshingly honest approach to art. He is an artist who is prepared to wait for the right shape, for the right brushstroke or the perfectly chosen word to express his meaning’. (Peter Murray (1)) Breon O’Casey was a true polymath and was possibly unique in the combination of skills he possessed over so many mediums in a single career. He was a painter, printmaker, weaver, sculptor and jewellery maker and it is hard to think of any other contemporary artist and maker who was so broadly talented. Son of the playwright Sean O’Casey (1880-1964), Breon spent most of his career in Cornwall, where he was closely associated with many of the painters, potters and sculptors of the St Ives movement. He arrived in the coastal town in the 1959 and served artistic apprenticeships under sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Denis Mitchell, and was friends with leading artists such as Peter Lanyon, John Wells and Tony O’Malley. In 1999 O’Casey recalled: ‘One day, watching television, some time in the late fifties, I saw a film about Alfred Wallis…the film incidentally showed St Ives and the studios of the artists living there. I realised it was the place for me. I owned a small orange Ford van. I packed the van and went. St Ives! In those days it was still a working fishing port, with tourism and artists tolerated, but kindly tolerated. Coming from Torquay, where I had felt like a rhinoceros walking along the streets, the relief of mingling with other crazy artists was enormous…I felt secure and there was a sort of electricity in the air.’ (2) O’Casey’s abstract style was poetic and focussed on discovering the simplicity of objects and forms. For him there was ‘nothing new under the sun, but an infinity of arrangements’ and when asked about objects that captivated him it was ‘not the wood, not the tree, but the leaf; not the distant view, but the hedge; not the mountain, but the stone’. He would return to geometric motifs and natural forms again and again throughout his career and considered himself a ‘traditional innovator’, fascinated by ancient, primitive and non-western art, but imbuing it with his own poetic sensibilities and discoveries through all the creative channels he explored. Although often overshadowed by his St Ives contemporaries, O’Casey’s legacy, talents and unique skills are now being reassessed, and greater importance given to his accomplishments beyond narrow and interlocked art circles. We are delighted to bring this collection of his work together to showcase many of the aspects of O’Casey’s prodigious artistic output, and to celebrate his significance as a true renaissance figure of British 20th-century art and craft. 1 / Peter Murray quoted in Sarah Coulson and Sophie Bowness, Breon O’Casey: An Anthology of his Writings, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, 2005, p.32 / Breon O’Casey quoted in Brian Fallon and Breon O’Casey, Breon O’Casey¸ Scolar Press, Aldershot, 1999, p.48.

§ Breon O'Casey (British 1928-2011) Two Pairs of Earrings the first modelled in silver of cirular lattice design, hallmarked for Birmingham 1981, makers mark; the second of circular outline with beaded detail, makers mark only, white metalDimensions:lattice 3.5cm diameter (1 3/8in diameter); beaded 3cm diameter (1 1/8in diameter) approximatelyProvenance:ProvenancePrivate Collection, Scotland.Note: ‘Breon O’Casey is a man for all seasons. He thinks and feels with his hands and moves with apparent ease from two-dimensional to three-dimensional activities, from one medium to another, without losing the artistic integrity of his intent. Breon O’Casey’s sensitive observations of life, art and nature inform his rich personal, visual language and beautifully balanced prose. His respect for his immediate environment and for tradition have enabled him to move forward with a confident, quiet ease, creating a refreshingly honest approach to art. He is an artist who is prepared to wait for the right shape, for the right brushstroke or the perfectly chosen word to express his meaning’. (Peter Murray (1)) Breon O’Casey was a true polymath and was possibly unique in the combination of skills he possessed over so many mediums in a single career. He was a painter, printmaker, weaver, sculptor and jewellery maker and it is hard to think of any other contemporary artist and maker who was so broadly talented. Son of the playwright Sean O’Casey (1880-1964), Breon spent most of his career in Cornwall, where he was closely associated with many of the painters, potters and sculptors of the St Ives movement. He arrived in the coastal town in the 1959 and served artistic apprenticeships under sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Denis Mitchell, and was friends with leading artists such as Peter Lanyon, John Wells and Tony O’Malley. In 1999 O’Casey recalled: ‘One day, watching television, some time in the late fifties, I saw a film about Alfred Wallis…the film incidentally showed St Ives and the studios of the artists living there. I realised it was the place for me. I owned a small orange Ford van. I packed the van and went. St Ives! In those days it was still a working fishing port, with tourism and artists tolerated, but kindly tolerated. Coming from Torquay, where I had felt like a rhinoceros walking along the streets, the relief of mingling with other crazy artists was enormous…I felt secure and there was a sort of electricity in the air.’ (2) O’Casey’s abstract style was poetic and focussed on discovering the simplicity of objects and forms. For him there was ‘nothing new under the sun, but an infinity of arrangements’ and when asked about objects that captivated him it was ‘not the wood, not the tree, but the leaf; not the distant view, but the hedge; not the mountain, but the stone’. He would return to geometric motifs and natural forms again and again throughout his career and considered himself a ‘traditional innovator’, fascinated by ancient, primitive and non-western art, but imbuing it with his own poetic sensibilities and discoveries through all the creative channels he explored. Although often overshadowed by his St Ives contemporaries, O’Casey’s legacy, talents and unique skills are now being reassessed, and greater importance given to his accomplishments beyond narrow and interlocked art circles. We are delighted to bring this collection of his work together to showcase many of the aspects of O’Casey’s prodigious artistic output, and to celebrate his significance as a true renaissance figure of British 20th-century art and craft. 1 / Peter Murray quoted in Sarah Coulson and Sophie Bowness, Breon O’Casey: An Anthology of his Writings, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, 2005, p.32 / Breon O’Casey quoted in Brian Fallon and Breon O’Casey, Breon O’Casey¸ Scolar Press, Aldershot, 1999, p.48.

Y § Breon O'Casey (British 1928-2011) Two Pairs of Earrings the first of pendent design with a coral bead, unmarked, yellow metal; the second of triangular outline, set with a green hardstone, unmarked, white metalDimensions:Lengths: 4cm and 0.9cm (1 1/2in and 2/5in)Provenance:ProvenancePrivate Collection, Scotland.Note: ‘Breon O’Casey is a man for all seasons. He thinks and feels with his hands and moves with apparent ease from two-dimensional to three-dimensional activities, from one medium to another, without losing the artistic integrity of his intent. Breon O’Casey’s sensitive observations of life, art and nature inform his rich personal, visual language and beautifully balanced prose. His respect for his immediate environment and for tradition have enabled him to move forward with a confident, quiet ease, creating a refreshingly honest approach to art. He is an artist who is prepared to wait for the right shape, for the right brushstroke or the perfectly chosen word to express his meaning’. (Peter Murray (1)) Breon O’Casey was a true polymath and was possibly unique in the combination of skills he possessed over so many mediums in a single career. He was a painter, printmaker, weaver, sculptor and jewellery maker and it is hard to think of any other contemporary artist and maker who was so broadly talented. Son of the playwright Sean O’Casey (1880-1964), Breon spent most of his career in Cornwall, where he was closely associated with many of the painters, potters and sculptors of the St Ives movement. He arrived in the coastal town in the 1959 and served artistic apprenticeships under sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Denis Mitchell, and was friends with leading artists such as Peter Lanyon, John Wells and Tony O’Malley. In 1999 O’Casey recalled: ‘One day, watching television, some time in the late fifties, I saw a film about Alfred Wallis…the film incidentally showed St Ives and the studios of the artists living there. I realised it was the place for me. I owned a small orange Ford van. I packed the van and went. St Ives! In those days it was still a working fishing port, with tourism and artists tolerated, but kindly tolerated. Coming from Torquay, where I had felt like a rhinoceros walking along the streets, the relief of mingling with other crazy artists was enormous…I felt secure and there was a sort of electricity in the air.’ (2) O’Casey’s abstract style was poetic and focussed on discovering the simplicity of objects and forms. For him there was ‘nothing new under the sun, but an infinity of arrangements’ and when asked about objects that captivated him it was ‘not the wood, not the tree, but the leaf; not the distant view, but the hedge; not the mountain, but the stone’. He would return to geometric motifs and natural forms again and again throughout his career and considered himself a ‘traditional innovator’, fascinated by ancient, primitive and non-western art, but imbuing it with his own poetic sensibilities and discoveries through all the creative channels he explored. Although often overshadowed by his St Ives contemporaries, O’Casey’s legacy, talents and unique skills are now being reassessed, and greater importance given to his accomplishments beyond narrow and interlocked art circles. We are delighted to bring this collection of his work together to showcase many of the aspects of O’Casey’s prodigious artistic output, and to celebrate his significance as a true renaissance figure of British 20th-century art and craft. 1 / Peter Murray quoted in Sarah Coulson and Sophie Bowness, Breon O’Casey: An Anthology of his Writings, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, 2005, p.32 / Breon O’Casey quoted in Brian Fallon and Breon O’Casey, Breon O’Casey¸ Scolar Press, Aldershot, 1999, p.48. Please be aware that all Lots marked with the symbol Y may be subject to CITES regulations when exporting these items outside Great Britain. These regulations may be found at https://www.defra.gov.uk/ahvla-en/imports-exports/citesWe accept no liability for any Lots which may be subject to CITES but have not be identified as such.

§ Breon O'Casey (British 1928-2011) Brooch scratch initials BOC, white metal, square outline with triangular motifsDimensions:3.8cm wide (1 1/2in wide)Provenance:Provenance Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1998.Note: ‘Breon O’Casey is a man for all seasons. He thinks and feels with his hands and moves with apparent ease from two-dimensional to three-dimensional activities, from one medium to another, without losing the artistic integrity of his intent. Breon O’Casey’s sensitive observations of life, art and nature inform his rich personal, visual language and beautifully balanced prose. His respect for his immediate environment and for tradition have enabled him to move forward with a confident, quiet ease, creating a refreshingly honest approach to art. He is an artist who is prepared to wait for the right shape, for the right brushstroke or the perfectly chosen word to express his meaning’. (Peter Murray (1)) Breon O’Casey was a true polymath and was possibly unique in the combination of skills he possessed over so many mediums in a single career. He was a painter, printmaker, weaver, sculptor and jewellery maker and it is hard to think of any other contemporary artist and maker who was so broadly talented. Son of the playwright Sean O’Casey (1880-1964), Breon spent most of his career in Cornwall, where he was closely associated with many of the painters, potters and sculptors of the St Ives movement. He arrived in the coastal town in the 1959 and served artistic apprenticeships under sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Denis Mitchell, and was friends with leading artists such as Peter Lanyon, John Wells and Tony O’Malley. In 1999 O’Casey recalled: ‘One day, watching television, some time in the late fifties, I saw a film about Alfred Wallis…the film incidentally showed St Ives and the studios of the artists living there. I realised it was the place for me. I owned a small orange Ford van. I packed the van and went. St Ives! In those days it was still a working fishing port, with tourism and artists tolerated, but kindly tolerated. Coming from Torquay, where I had felt like a rhinoceros walking along the streets, the relief of mingling with other crazy artists was enormous…I felt secure and there was a sort of electricity in the air.’ (2) O’Casey’s abstract style was poetic and focussed on discovering the simplicity of objects and forms. For him there was ‘nothing new under the sun, but an infinity of arrangements’ and when asked about objects that captivated him it was ‘not the wood, not the tree, but the leaf; not the distant view, but the hedge; not the mountain, but the stone’. He would return to geometric motifs and natural forms again and again throughout his career and considered himself a ‘traditional innovator’, fascinated by ancient, primitive and non-western art, but imbuing it with his own poetic sensibilities and discoveries through all the creative channels he explored. Although often overshadowed by his St Ives contemporaries, O’Casey’s legacy, talents and unique skills are now being reassessed, and greater importance given to his accomplishments beyond narrow and interlocked art circles. We are delighted to bring this collection of his work together to showcase many of the aspects of O’Casey’s prodigious artistic output, and to celebrate his significance as a true renaissance figure of British 20th-century art and craft. 1 / Peter Murray quoted in Sarah Coulson and Sophie Bowness, Breon O’Casey: An Anthology of his Writings, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, 2005, p.32 / Breon O’Casey quoted in Brian Fallon and Breon O’Casey, Breon O’Casey¸ Scolar Press, Aldershot, 1999, p.48.

§ Breon O'Casey (British 1928-2011) Bather signed BOC and numbered I/V (to marble base), bronzeDimensions:26.5cm high (10 1/2in high) excluding baseProvenance:ProvenancePrivate Collection, London.Note: ‘Breon O’Casey is a man for all seasons. He thinks and feels with his hands and moves with apparent ease from two-dimensional to three-dimensional activities, from one medium to another, without losing the artistic integrity of his intent. Breon O’Casey’s sensitive observations of life, art and nature inform his rich personal, visual language and beautifully balanced prose. His respect for his immediate environment and for tradition have enabled him to move forward with a confident, quiet ease, creating a refreshingly honest approach to art. He is an artist who is prepared to wait for the right shape, for the right brushstroke or the perfectly chosen word to express his meaning’. (Peter Murray (1)) Breon O’Casey was a true polymath and was possibly unique in the combination of skills he possessed over so many mediums in a single career. He was a painter, printmaker, weaver, sculptor and jewellery maker and it is hard to think of any other contemporary artist and maker who was so broadly talented. Son of the playwright Sean O’Casey (1880-1964), Breon spent most of his career in Cornwall, where he was closely associated with many of the painters, potters and sculptors of the St Ives movement. He arrived in the coastal town in the 1959 and served artistic apprenticeships under sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Denis Mitchell, and was friends with leading artists such as Peter Lanyon, John Wells and Tony O’Malley. In 1999 O’Casey recalled: ‘One day, watching television, some time in the late fifties, I saw a film about Alfred Wallis…the film incidentally showed St Ives and the studios of the artists living there. I realised it was the place for me. I owned a small orange Ford van. I packed the van and went. St Ives! In those days it was still a working fishing port, with tourism and artists tolerated, but kindly tolerated. Coming from Torquay, where I had felt like a rhinoceros walking along the streets, the relief of mingling with other crazy artists was enormous…I felt secure and there was a sort of electricity in the air.’ (2) O’Casey’s abstract style was poetic and focussed on discovering the simplicity of objects and forms. For him there was ‘nothing new under the sun, but an infinity of arrangements’ and when asked about objects that captivated him it was ‘not the wood, not the tree, but the leaf; not the distant view, but the hedge; not the mountain, but the stone’. He would return to geometric motifs and natural forms again and again throughout his career and considered himself a ‘traditional innovator’, fascinated by ancient, primitive and non-western art, but imbuing it with his own poetic sensibilities and discoveries through all the creative channels he explored. Although often overshadowed by his St Ives contemporaries, O’Casey’s legacy, talents and unique skills are now being reassessed, and greater importance given to his accomplishments beyond narrow and interlocked art circles. We are delighted to bring this collection of his work together to showcase many of the aspects of O’Casey’s prodigious artistic output, and to celebrate his significance as a true renaissance figure of British 20th-century art and craft. 1 / Peter Murray quoted in Sarah Coulson and Sophie Bowness, Breon O’Casey: An Anthology of his Writings, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, 2005, p.32 / Breon O’Casey quoted in Brian Fallon and Breon O’Casey, Breon O’Casey¸ Scolar Press, Aldershot, 1999, p.48.

§ Breon O'Casey (British 1928-2011) Cockerel stamped BOC (to base), bronzeDimensions:9.3cm high, 7in wide (3 5/8in high, 2 3/4in wide)Provenance:ProvenancePrivate Collection, London.Note: ‘Breon O’Casey is a man for all seasons. He thinks and feels with his hands and moves with apparent ease from two-dimensional to three-dimensional activities, from one medium to another, without losing the artistic integrity of his intent. Breon O’Casey’s sensitive observations of life, art and nature inform his rich personal, visual language and beautifully balanced prose. His respect for his immediate environment and for tradition have enabled him to move forward with a confident, quiet ease, creating a refreshingly honest approach to art. He is an artist who is prepared to wait for the right shape, for the right brushstroke or the perfectly chosen word to express his meaning’. (Peter Murray (1)) Breon O’Casey was a true polymath and was possibly unique in the combination of skills he possessed over so many mediums in a single career. He was a painter, printmaker, weaver, sculptor and jewellery maker and it is hard to think of any other contemporary artist and maker who was so broadly talented. Son of the playwright Sean O’Casey (1880-1964), Breon spent most of his career in Cornwall, where he was closely associated with many of the painters, potters and sculptors of the St Ives movement. He arrived in the coastal town in the 1959 and served artistic apprenticeships under sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Denis Mitchell, and was friends with leading artists such as Peter Lanyon, John Wells and Tony O’Malley. In 1999 O’Casey recalled: ‘One day, watching television, some time in the late fifties, I saw a film about Alfred Wallis…the film incidentally showed St Ives and the studios of the artists living there. I realised it was the place for me. I owned a small orange Ford van. I packed the van and went. St Ives! In those days it was still a working fishing port, with tourism and artists tolerated, but kindly tolerated. Coming from Torquay, where I had felt like a rhinoceros walking along the streets, the relief of mingling with other crazy artists was enormous…I felt secure and there was a sort of electricity in the air.’ (2) O’Casey’s abstract style was poetic and focussed on discovering the simplicity of objects and forms. For him there was ‘nothing new under the sun, but an infinity of arrangements’ and when asked about objects that captivated him it was ‘not the wood, not the tree, but the leaf; not the distant view, but the hedge; not the mountain, but the stone’. He would return to geometric motifs and natural forms again and again throughout his career and considered himself a ‘traditional innovator’, fascinated by ancient, primitive and non-western art, but imbuing it with his own poetic sensibilities and discoveries through all the creative channels he explored. Although often overshadowed by his St Ives contemporaries, O’Casey’s legacy, talents and unique skills are now being reassessed, and greater importance given to his accomplishments beyond narrow and interlocked art circles. We are delighted to bring this collection of his work together to showcase many of the aspects of O’Casey’s prodigious artistic output, and to celebrate his significance as a true renaissance figure of British 20th-century art and craft. 1 / Peter Murray quoted in Sarah Coulson and Sophie Bowness, Breon O’Casey: An Anthology of his Writings, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, 2005, p.32 / Breon O’Casey quoted in Brian Fallon and Breon O’Casey, Breon O’Casey¸ Scolar Press, Aldershot, 1999, p.48.

§ Breon O'Casey (British 1928-2011) Bird in the Wood, 2008 signed, titled and dated (to reverse), acrylic on canvasDimensions:91cm x 121cm (35 3/4in x 47 5/8in)Provenance:ProvenanceClark Art Ltd, Hale;Private Collection, UK.Note: LiteratureFallon, Brian, Breon O'Casey: A Decade, Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1999, p. 63, illustrated. ‘Breon O’Casey is a man for all seasons. He thinks and feels with his hands and moves with apparent ease from two-dimensional to three-dimensional activities, from one medium to another, without losing the artistic integrity of his intent. Breon O’Casey’s sensitive observations of life, art and nature inform his rich personal, visual language and beautifully balanced prose. His respect for his immediate environment and for tradition have enabled him to move forward with a confident, quiet ease, creating a refreshingly honest approach to art. He is an artist who is prepared to wait for the right shape, for the right brushstroke or the perfectly chosen word to express his meaning’. (Peter Murray (1)) Breon O’Casey was a true polymath and was possibly unique in the combination of skills he possessed over so many mediums in a single career. He was a painter, printmaker, weaver, sculptor and jewellery maker and it is hard to think of any other contemporary artist and maker who was so broadly talented. Son of the playwright Sean O’Casey (1880-1964), Breon spent most of his career in Cornwall, where he was closely associated with many of the painters, potters and sculptors of the St Ives movement. He arrived in the coastal town in the 1959 and served artistic apprenticeships under sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Denis Mitchell, and was friends with leading artists such as Peter Lanyon, John Wells and Tony O’Malley. In 1999 O’Casey recalled: ‘One day, watching television, some time in the late fifties, I saw a film about Alfred Wallis…the film incidentally showed St Ives and the studios of the artists living there. I realised it was the place for me. I owned a small orange Ford van. I packed the van and went. St Ives! In those days it was still a working fishing port, with tourism and artists tolerated, but kindly tolerated. Coming from Torquay, where I had felt like a rhinoceros walking along the streets, the relief of mingling with other crazy artists was enormous…I felt secure and there was a sort of electricity in the air.’ (2) O’Casey’s abstract style was poetic and focussed on discovering the simplicity of objects and forms. For him there was ‘nothing new under the sun, but an infinity of arrangements’ and when asked about objects that captivated him it was ‘not the wood, not the tree, but the leaf; not the distant view, but the hedge; not the mountain, but the stone’. He would return to geometric motifs and natural forms again and again throughout his career and considered himself a ‘traditional innovator’, fascinated by ancient, primitive and non-western art, but imbuing it with his own poetic sensibilities and discoveries through all the creative channels he explored. Although often overshadowed by his St Ives contemporaries, O’Casey’s legacy, talents and unique skills are now being reassessed, and greater importance given to his accomplishments beyond narrow and interlocked art circles. We are delighted to bring this collection of his work together to showcase many of the aspects of O’Casey’s prodigious artistic output, and to celebrate his significance as a true renaissance figure of British 20th-century art and craft. 1 / Peter Murray quoted in Sarah Coulson and Sophie Bowness, Breon O’Casey: An Anthology of his Writings, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, 2005, p.32 / Breon O’Casey quoted in Brian Fallon and Breon O’Casey, Breon O’Casey¸ Scolar Press, Aldershot, 1999, p.48.

§ Breon O'Casey (British 1928-2011) Two Tie Designs Mixed media and collageDimensions:28.5cm x 19cm (11 1/4in x 7 1/2in)Provenance:ProvenanceThe Estate of an important St. Ives artist.Note: ‘Breon O’Casey is a man for all seasons. He thinks and feels with his hands and moves with apparent ease from two-dimensional to three-dimensional activities, from one medium to another, without losing the artistic integrity of his intent. Breon O’Casey’s sensitive observations of life, art and nature inform his rich personal, visual language and beautifully balanced prose. His respect for his immediate environment and for tradition have enabled him to move forward with a confident, quiet ease, creating a refreshingly honest approach to art. He is an artist who is prepared to wait for the right shape, for the right brushstroke or the perfectly chosen word to express his meaning’. (Peter Murray (1)) Breon O’Casey was a true polymath and was possibly unique in the combination of skills he possessed over so many mediums in a single career. He was a painter, printmaker, weaver, sculptor and jewellery maker and it is hard to think of any other contemporary artist and maker who was so broadly talented. Son of the playwright Sean O’Casey (1880-1964), Breon spent most of his career in Cornwall, where he was closely associated with many of the painters, potters and sculptors of the St Ives movement. He arrived in the coastal town in the 1959 and served artistic apprenticeships under sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Denis Mitchell, and was friends with leading artists such as Peter Lanyon, John Wells and Tony O’Malley. In 1999 O’Casey recalled: ‘One day, watching television, some time in the late fifties, I saw a film about Alfred Wallis…the film incidentally showed St Ives and the studios of the artists living there. I realised it was the place for me. I owned a small orange Ford van. I packed the van and went. St Ives! In those days it was still a working fishing port, with tourism and artists tolerated, but kindly tolerated. Coming from Torquay, where I had felt like a rhinoceros walking along the streets, the relief of mingling with other crazy artists was enormous…I felt secure and there was a sort of electricity in the air.’ (2) O’Casey’s abstract style was poetic and focussed on discovering the simplicity of objects and forms. For him there was ‘nothing new under the sun, but an infinity of arrangements’ and when asked about objects that captivated him it was ‘not the wood, not the tree, but the leaf; not the distant view, but the hedge; not the mountain, but the stone’. He would return to geometric motifs and natural forms again and again throughout his career and considered himself a ‘traditional innovator’, fascinated by ancient, primitive and non-western art, but imbuing it with his own poetic sensibilities and discoveries through all the creative channels he explored. Although often overshadowed by his St Ives contemporaries, O’Casey’s legacy, talents and unique skills are now being reassessed, and greater importance given to his accomplishments beyond narrow and interlocked art circles. We are delighted to bring this collection of his work together to showcase many of the aspects of O’Casey’s prodigious artistic output, and to celebrate his significance as a true renaissance figure of British 20th-century art and craft. 1 / Peter Murray quoted in Sarah Coulson and Sophie Bowness, Breon O’Casey: An Anthology of his Writings, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, 2005, p.32 / Breon O’Casey quoted in Brian Fallon and Breon O’Casey, Breon O’Casey¸ Scolar Press, Aldershot, 1999, p.48.

§ Breon O'Casey (British 1928-2011) Christmas Card (Bird Design) Inscribed (inside card), linocutDimensions:23cm x 15.5cm (9in x 6in)Provenance:ProvenanceThe Estate of an important St. Ives artist.Note: ‘Breon O’Casey is a man for all seasons. He thinks and feels with his hands and moves with apparent ease from two-dimensional to three-dimensional activities, from one medium to another, without losing the artistic integrity of his intent. Breon O’Casey’s sensitive observations of life, art and nature inform his rich personal, visual language and beautifully balanced prose. His respect for his immediate environment and for tradition have enabled him to move forward with a confident, quiet ease, creating a refreshingly honest approach to art. He is an artist who is prepared to wait for the right shape, for the right brushstroke or the perfectly chosen word to express his meaning’. (Peter Murray (1)) Breon O’Casey was a true polymath and was possibly unique in the combination of skills he possessed over so many mediums in a single career. He was a painter, printmaker, weaver, sculptor and jewellery maker and it is hard to think of any other contemporary artist and maker who was so broadly talented. Son of the playwright Sean O’Casey (1880-1964), Breon spent most of his career in Cornwall, where he was closely associated with many of the painters, potters and sculptors of the St Ives movement. He arrived in the coastal town in the 1959 and served artistic apprenticeships under sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Denis Mitchell, and was friends with leading artists such as Peter Lanyon, John Wells and Tony O’Malley. In 1999 O’Casey recalled: ‘One day, watching television, some time in the late fifties, I saw a film about Alfred Wallis…the film incidentally showed St Ives and the studios of the artists living there. I realised it was the place for me. I owned a small orange Ford van. I packed the van and went. St Ives! In those days it was still a working fishing port, with tourism and artists tolerated, but kindly tolerated. Coming from Torquay, where I had felt like a rhinoceros walking along the streets, the relief of mingling with other crazy artists was enormous…I felt secure and there was a sort of electricity in the air.’ (2) O’Casey’s abstract style was poetic and focussed on discovering the simplicity of objects and forms. For him there was ‘nothing new under the sun, but an infinity of arrangements’ and when asked about objects that captivated him it was ‘not the wood, not the tree, but the leaf; not the distant view, but the hedge; not the mountain, but the stone’. He would return to geometric motifs and natural forms again and again throughout his career and considered himself a ‘traditional innovator’, fascinated by ancient, primitive and non-western art, but imbuing it with his own poetic sensibilities and discoveries through all the creative channels he explored. Although often overshadowed by his St Ives contemporaries, O’Casey’s legacy, talents and unique skills are now being reassessed, and greater importance given to his accomplishments beyond narrow and interlocked art circles. We are delighted to bring this collection of his work together to showcase many of the aspects of O’Casey’s prodigious artistic output, and to celebrate his significance as a true renaissance figure of British 20th-century art and craft. 1 / Peter Murray quoted in Sarah Coulson and Sophie Bowness, Breon O’Casey: An Anthology of his Writings, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, 2005, p.32 / Breon O’Casey quoted in Brian Fallon and Breon O’Casey, Breon O’Casey¸ Scolar Press, Aldershot, 1999, p.48.

§ Breon O'Casey (British 1928-2011) Three Christmas Cards each inscribed from the artist (inside the card), mixed media, mixed media with collage and linocutDimensions:11.5cm x 17.5cm (4 1/2in x 7in); 10cm x 17cm (4in x 6 3/4in); 19.5cm x 20cm (7 3/4in x 8in);Provenance:ProvenanceThe Estate of an important St. Ives artist.Note: ‘Breon O’Casey is a man for all seasons. He thinks and feels with his hands and moves with apparent ease from two-dimensional to three-dimensional activities, from one medium to another, without losing the artistic integrity of his intent. Breon O’Casey’s sensitive observations of life, art and nature inform his rich personal, visual language and beautifully balanced prose. His respect for his immediate environment and for tradition have enabled him to move forward with a confident, quiet ease, creating a refreshingly honest approach to art. He is an artist who is prepared to wait for the right shape, for the right brushstroke or the perfectly chosen word to express his meaning’. (Peter Murray (1)) Breon O’Casey was a true polymath and was possibly unique in the combination of skills he possessed over so many mediums in a single career. He was a painter, printmaker, weaver, sculptor and jewellery maker and it is hard to think of any other contemporary artist and maker who was so broadly talented. Son of the playwright Sean O’Casey (1880-1964), Breon spent most of his career in Cornwall, where he was closely associated with many of the painters, potters and sculptors of the St Ives movement. He arrived in the coastal town in the 1959 and served artistic apprenticeships under sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Denis Mitchell, and was friends with leading artists such as Peter Lanyon, John Wells and Tony O’Malley. In 1999 O’Casey recalled: ‘One day, watching television, some time in the late fifties, I saw a film about Alfred Wallis…the film incidentally showed St Ives and the studios of the artists living there. I realised it was the place for me. I owned a small orange Ford van. I packed the van and went. St Ives! In those days it was still a working fishing port, with tourism and artists tolerated, but kindly tolerated. Coming from Torquay, where I had felt like a rhinoceros walking along the streets, the relief of mingling with other crazy artists was enormous…I felt secure and there was a sort of electricity in the air.’ (2) O’Casey’s abstract style was poetic and focussed on discovering the simplicity of objects and forms. For him there was ‘nothing new under the sun, but an infinity of arrangements’ and when asked about objects that captivated him it was ‘not the wood, not the tree, but the leaf; not the distant view, but the hedge; not the mountain, but the stone’. He would return to geometric motifs and natural forms again and again throughout his career and considered himself a ‘traditional innovator’, fascinated by ancient, primitive and non-western art, but imbuing it with his own poetic sensibilities and discoveries through all the creative channels he explored. Although often overshadowed by his St Ives contemporaries, O’Casey’s legacy, talents and unique skills are now being reassessed, and greater importance given to his accomplishments beyond narrow and interlocked art circles. We are delighted to bring this collection of his work together to showcase many of the aspects of O’Casey’s prodigious artistic output, and to celebrate his significance as a true renaissance figure of British 20th-century art and craft. 1 / Peter Murray quoted in Sarah Coulson and Sophie Bowness, Breon O’Casey: An Anthology of his Writings, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, 2005, p.32 / Breon O’Casey quoted in Brian Fallon and Breon O’Casey, Breon O’Casey¸ Scolar Press, Aldershot, 1999, p.48.

§ Fulvio Bianconi (Italian 1915-1996) for Venini 'Arlechino' Pezzato vase, 1950 model 4319, signed with 3 line acid stamp Venini, Murano, ITALIA (to base), glassDimensions:36cm high (14 1/4in high)Provenance:ProvenancePrivate Collection, UK.Note: LiteratureBarovier, Marino and Carla Sonego. Fulvio Bianconi at Venini. SKIRA. p 181;‘Fulvio Bianconi at Venini’ Catalogue of the exhibition at Le Stanze del Vetro (The Glass rooms) in Venice in 2015 by Marino Barovier and Carla Sonego, page 181.‘Venetian Glass’ the Nancy Olnick and George Spanau collection. Exhibition catalogue Autumn 2000 American Craft Museum, page 116 and 219,‘Italian Glass, Murano – Milan 1930-1970’, The Steinberg Foundation Collection catalogue by Ricke and Schmitt 1997, plate 83 page 109. The Pezzato vase was one of the most successful designs that Fulvio Bianconi created for Venini. Bianconi used a glass mosaic in various ways producing brilliant chromatic effects. These vases were first exhibited at the 25th Venice Biennale in 1950. The glass tesserae are first made from coloured glass canes flattened and cut to various sizes before being arranged into a mosaic. The mosaic is then heated on a fire stone to weld the different colours together. They are then picked up on a blank to form the walls of the final piece. The glass is then blown and hot worked into the desired form. Most of the designs were in transparent glass but there are also some made from a combination of opaque pasta vitrea and transparent tesserae which became known as ‘Arlecchino’ designs and had the greatest chromatic brilliance.

Robert Sgarra (French, 1959 -)'Black Dollar'2021Acrylic, spray paint & resin mixed mediaLimited edition 1 of 7 Signed & numbered to frontFirst NFT model77 x 181 cm (30" x 71")Robert Sgarra was born n Grenoble in 1959. He lives and works in the South of France. Robert Sgarra is a self-taught artist who started painting at the age of thirteen and has been exploring many artistic fields ever since. He is the son of an Italian immigrant father. An artist fascinated by all forms of art, his paintings are inspired by Picasso, Nicolas de Stael, Braque and Matisse. The influence of Léonardo da Vinci can be seen in his sculptures. A wizard of materials and an artist difficult to label, Robert Sgarra revisits pop art as a dedicated colorist in innovative and inventive works, sometimes also daring to use extreme colors. He varies his shapes and colors, in tune with his humor and moods, always spurred and driven to create. In the 1990's he used collage and acrylic on stone to portray celebrities such as Zidane, Luis Fernandez, Patrick Viera, Baresi, Karpov and Pinna.This lot is also sold subject to Artists Resale Rights, details of which can be found in our Terms and Conditions.

Gilles Coignet by Sadeler - Sine Cerere et Baccho friget Venvs. / Description: Venus, Bacchus and Ceres. Venus seated at the foot of a tree at centre, her foot resting on a stone block, Bacchus at left with wine leaves in his hair, Ceres at right and seen from behind with vegetables in her arms, Cupid holding an arrow next to Venus. Engraving made and published by Raphael Sadeler after Gillis Coignet (1542-1599). Signed in lower corners of impression: "Gillis Coingnet inuentor." and "Raphael Sadler f. et excud.". In lower part on a stone block: "Sine Cerere et Baccho / friget Venvs.". / Dimensions: 19,80 x 24,70 / Condition: A good impression trimmed on plate border with traces of tread margins. A few closed defects near the borderline, restored with a paper fragment on the top stone visible near the bottom left corner and a paper strip on the backside of Bacchus. Remains of former album tipping on the backside. Hollstein / Dutch and Flemish etchings, engravings and woodcuts c.1450-1700 (175) Engraving /Circa: 1580-1620

-

400965 item(s)/page