A Greek terracotta head of a female with melon coiffure, with traces of white pigment remaining, 4.8cm high; a Greek squat terracotta vessel, 4.7cm high, mounted; a terracotta spout from an ancient vessel, 4.3cm high; a miniature Roman style bronze oil lamp, with a slender nozzle, handle missing, 7.5cm long; an Egyptian style brown stone scarab with text on the underside of the base, 5.9cm long, and an Egyptian style faience necklace composed of cylindrical beads interspersed with spherical beads and a scarab hanging pendant (6)

We found 400830 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 400830 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

400830 item(s)/page

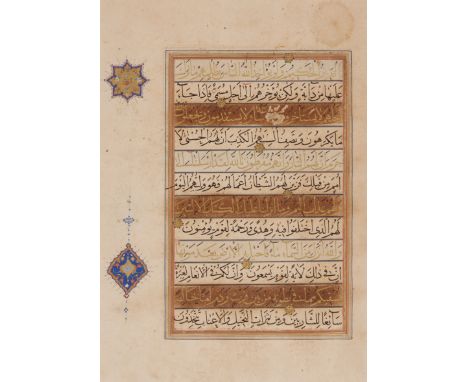

A Quran folio in Muhaqqaq, Shiraz, Iran, circa 1525-1550, Arabic manuscript on paper, a single folio from a Qur'an with 12 ll. of Muhaqqaq to the page in black and gold, each line written within a ruled panel on varying coloured ground, a practice extremely rare in any period, verse markers of illuminated six-pointed stars in gold circles, the text bordered to the left by decorative motifs that mark the fifth and tenth verses - a fine eight-pointed, blue-bordered star with a golden centre and a brightly coloured floral design - and a cartouche richly illuminated in gold and colour, filled with arabesque and a central palmette, folio 44 cm high; 29.5 cm diam.Published: Paper Parchment Steel & Stone, Calligraphy and the Arts of Islam from the 8th to the 19th century, exhibition catalogue, Spink, 27 April - 15 May 1 1998, no. 12;Another folio is in the Khalili Collection of Islamic Art and illustrated in David James, 'After Timur', 1992, Qur'ans of the 15th and 16th Centuries, no. 42, pp. 170-171

Six Egyptian glazed faience amulets and shabtis, including a large amulet of Bes standing with feathered headdress, some blue glaze remaining, 9.3cm high, on a tall stone base; a large fragmentary striding Taueret with pendulous breasts and traces of blue glaze remaining, 8.5cm high, with an ink inscribed paper label on the back, mounted; a squatting figure of Thoth as a baboon, with blue glaze and added black dots, 6.2cm high, ,on a tall stone mount; a small openwork figure of Bes, 5cm high, with an ink inscribed paper label on the back, on an amethyst pedestal base; two shabti figures, one with black ink inscribed hieroglyphs and details, 10.3cm high and 9.2cm high, the latter with an ink inscribed paper label on the back, some possibly ancient (6)

Approximately 200 film and tv promotional posters, to include Harry Potter And The Philosopher's Stone, Liar Liar, The Grinch, Resident Evil, Summer Of Sam, Battlefield Earth, Austin Powers Goldmember, Winnie The Pooh, Scooby-Doo, Eye Of The Beholder, The Talented Mr Ripley, Frank Herbert's Dune and others, 60cm x 42cm (approximate size but various sizes included), some duplicates

§ George Kennethson (British 1910-1994) Wave Form, circa 1950s-60s Clipsham stoneDimensions:43cm high, 30.5cm wide, 20cm deep (17in high, 12in wide, 7 3/4in deep)Provenance:ProvenanceThe Estate of the Artist.Note: LiteratureCork, Richard. The Sculpture of George Kennethson, Redfern Gallery, London, 2014, p. 20 illustrated in the background of a photograph of the artist's studio. George Kennethson (or Arthur Mackenzie as he was, Kennethson being the name he adopted in the early 1970s in order to separate his artistic practice from his role as the art master at Oundle School) met Eileen Guthrie in 1931 at the Royal Academy Schools in London. Intriguingly both were painting students, although in George’s case, the teaching at the still very academic Academy mainly had the effect of turning him into a sculptor, something he was already considering by his final year when the pair of them met [although one of his sons recalls Kennethson generously saying that the reason he became a sculptor was that Eileen was by far the better painter].George had come from a cultured, literary family. Eileen’s father and grandfather were architects and her mother was an accomplished pianist, who had studied at the Royal College of Music [Eileen herself had been taught piano by Gustav Holst when she was young]. And so, like many of their circle, Eileen and George were left-wing in their politics, interested in all things avant-garde in art, music and literature, and looked to Paris for inspiration. As young artists they both revered Cezanne. On their first trip together to the French capital, George tracked down the work of sculptors Maillol, Zadkine and Brancusi. And Eileen no doubt sought out the work of Bonnard, whose influence, both in composition and technique, can be traced in her work. They returned, in 1937, where they saw Picasso’s recently completed Guernica, which moved them both, artistically and politically. Like many artists of their generation, their lives and careers were profoundly affected by the Second World War. The Kennethsons were committed pacifists. A year before war broke out, they had moved to the quiet Berkshire village of Uffington, watched over by its ancient, curiously abstract White Horse, cut into the chalk of the nearby Downs, and so in away had already withdrawn from the political storm of the late 30s. The local villagers had no issues with the Kennethsons’ avowed pacifism: they were artists, after all, so they expected them to be different. Whilst they passed the war in rural seclusion, conflict does seep into Kennethson’s sculpture, such as sculptures of travellers, with staffs and backpacks, or men carrying mattresses down to the local forge – images glimpsed out of the studio window, but now transformed into a moving response to the refugees that war inevitably creates. The couple took in both evacuees from the Blitz and the occasional European refugee (and much later in the 1980s, Kennethson returned to this theme as a response to the migrations forced by famine in Ethiopia). But more than this, the War and its aftermath led to little opportunity for artists to sell their work and therefore live by their art – something that was particularly acute for the Kennethsons, who by the late 1940s had five young boys to feed. Art historians have often been critical of British artists ‘retreating’ into teaching or commercial work, whilst their counterparts in America were splashing newly made paint across acres of pristine canvas and changing the direction of modern art forever, and yet this ignores the pressures on British artists, facing a public that was already relatively indifferent to modern art already and which now was broke.It was at this point that Eileen turned her hand to making prints for textiles. She did so with incredible success – artistically at least, as there was almost as little money for interiors and design in post-war Britain as there was for at. Eileen did, however, sell her ‘Flockhart Fabrics’ range – named after her Scottish grandfather - at Primavera, a leading interiors shop on Sloane Street, as well as to family and friends. Their neighbour in Uffington, John Betjeman, also helped them to find stockists, and Eileen’s twin sister Joan would open her London flat to showcase the designs. Lucienne Day, too, introduced Eileen to Amersham Prints, contractors to the government, and her design Bird and Basket was used in 1954 to furnish the Morag Mhor, the first all-aluminium yacht in the country.George lent a hand too, on the production side, contributing to designs, working on the lino-blocks and silkscreens and helping Eileen with the considerable manual work of printing the fabrics by hand. The prints are deceptively simple, strong and sculptural, whilst retaining the required elegance and beauty. The line that one sees in her gouaches and oils find an easy home amongst the repeats of fabric design and motifs that infuse George’s sculpture – birds, leaves, architectonic flower forms – are abstracted from her landscape painting.The family moved to Oundle in 1954, to a house with a large former malting attached, which made for good, if draughty, studios. George would have been surrounded by Eileen’s fabrics – at the long settle by the kitchen table or on one of the armchairs where he would read and draw- before heading out to his studio to carve equally simple forms, with soft curves and sharp edges, into stone and alabaster, so perhaps Eileen’s influence on George’s work shouldn’t be under-estimated. Meeting her late in her life – a decade after George’s death – she would walk amongst the sculptures, laid out on plinths in a cavernous Victorian former malting attached to their house, and place her hands intuitively on every undercut and turn (the wearing of rings was strictly forbidden!). George resolutely worked alone – no assistants, no power tools, only mallets and chisels and cassettes of classical music and operatic arias for company – but the confluence between their work speaks to a shared vision. We are delighted to include in this selection a painting by Eileen alongside a drawing of George’s, both made at their beloved Isle of Purbeck, where they had holidayed (and found inspiration, in the fields, quarries and shore) every year since the late 1930s. Seen side by side, these works could almost be by the same hand. George’s drawings, mainly of the rock formations of the coast that were the source of his material, whilst studies in sculptural form, have a painter’s confident flow: equally, Eileen’s paintings, whilst more concerned with the wider landscape, have a certain sculptural feel to their construction, even though, in the end, they concern themselves more with colour and abstract form, in the manner of Ivon Hitchens or Patrick Heron, both of whom she admired. The last few years have seen something of a revival in interest in George Kennethson’s work. After all, this is an artist whose work sits very comfortably – and beautifully – in Britain’s best small museum, Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, alongside Constantin Brancusi and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. There are now two monographs on the artist, the most recent written by the eminent critic Richard Cork. Eileen Guthrie’s work, on the other hand, still remains something of a secret, her last public exhibitions being held almost 40 years ago now. We hope that this brief glimpse will be the beginning of her revival, as well as a testament an artistic partnership that was very much of its time, yet resonates with beauty today.

§ George Kennethson (British 1910-1994) Girl's Back with Curled Hair - Study for Sculpture, circa 1960 ink and wash on paperDimensions:16cm x 12.5cm (6 3/8in x 4 7/8in)Provenance:ProvenanceThe Estate of the Artist.Note: LiteratureHucker, Simon. George Kennethson: A Modernist Rediscovered. London: Merrell Publishers Limited, 2004, p.14, illustrated. George Kennethson (or Arthur Mackenzie as he was, Kennethson being the name he adopted in the early 1970s in order to separate his artistic practice from his role as the art master at Oundle School) met Eileen Guthrie in 1931 at the Royal Academy Schools in London. Intriguingly both were painting students, although in George’s case, the teaching at the still very academic Academy mainly had the effect of turning him into a sculptor, something he was already considering by his final year when the pair of them met [although one of his sons recalls Kennethson generously saying that the reason he became a sculptor was that Eileen was by far the better painter].George had come from a cultured, literary family. Eileen’s father and grandfather were architects and her mother was an accomplished pianist, who had studied at the Royal College of Music [Eileen herself had been taught piano by Gustav Holst when she was young]. And so, like many of their circle, Eileen and George were left-wing in their politics, interested in all things avant-garde in art, music and literature, and looked to Paris for inspiration. As young artists they both revered Cezanne. On their first trip together to the French capital, George tracked down the work of sculptors Maillol, Zadkine and Brancusi. And Eileen no doubt sought out the work of Bonnard, whose influence, both in composition and technique, can be traced in her work. They returned, in 1937, where they saw Picasso’s recently completed Guernica, which moved them both, artistically and politically. Like many artists of their generation, their lives and careers were profoundly affected by the Second World War. The Kennethsons were committed pacifists. A year before war broke out, they had moved to the quiet Berkshire village of Uffington, watched over by its ancient, curiously abstract White Horse, cut into the chalk of the nearby Downs, and so in away had already withdrawn from the political storm of the late 30s. The local villagers had no issues with the Kennethsons’ avowed pacifism: they were artists, after all, so they expected them to be different. Whilst they passed the war in rural seclusion, conflict does seep into Kennethson’s sculpture, such as sculptures of travellers, with staffs and backpacks, or men carrying mattresses down to the local forge – images glimpsed out of the studio window, but now transformed into a moving response to the refugees that war inevitably creates. The couple took in both evacuees from the Blitz and the occasional European refugee (and much later in the 1980s, Kennethson returned to this theme as a response to the migrations forced by famine in Ethiopia). But more than this, the War and its aftermath led to little opportunity for artists to sell their work and therefore live by their art – something that was particularly acute for the Kennethsons, who by the late 1940s had five young boys to feed. Art historians have often been critical of British artists ‘retreating’ into teaching or commercial work, whilst their counterparts in America were splashing newly made paint across acres of pristine canvas and changing the direction of modern art forever, and yet this ignores the pressures on British artists, facing a public that was already relatively indifferent to modern art already and which now was broke.It was at this point that Eileen turned her hand to making prints for textiles. She did so with incredible success – artistically at least, as there was almost as little money for interiors and design in post-war Britain as there was for at. Eileen did, however, sell her ‘Flockhart Fabrics’ range – named after her Scottish grandfather - at Primavera, a leading interiors shop on Sloane Street, as well as to family and friends. Their neighbour in Uffington, John Betjeman, also helped them to find stockists, and Eileen’s twin sister Joan would open her London flat to showcase the designs. Lucienne Day, too, introduced Eileen to Amersham Prints, contractors to the government, and her design Bird and Basket was used in 1954 to furnish the Morag Mhor, the first all-aluminium yacht in the country.George lent a hand too, on the production side, contributing to designs, working on the lino-blocks and silkscreens and helping Eileen with the considerable manual work of printing the fabrics by hand. The prints are deceptively simple, strong and sculptural, whilst retaining the required elegance and beauty. The line that one sees in her gouaches and oils find an easy home amongst the repeats of fabric design and motifs that infuse George’s sculpture – birds, leaves, architectonic flower forms – are abstracted from her landscape painting.The family moved to Oundle in 1954, to a house with a large former malting attached, which made for good, if draughty, studios. George would have been surrounded by Eileen’s fabrics – at the long settle by the kitchen table or on one of the armchairs where he would read and draw- before heading out to his studio to carve equally simple forms, with soft curves and sharp edges, into stone and alabaster, so perhaps Eileen’s influence on George’s work shouldn’t be under-estimated. Meeting her late in her life – a decade after George’s death – she would walk amongst the sculptures, laid out on plinths in a cavernous Victorian former malting attached to their house, and place her hands intuitively on every undercut and turn (the wearing of rings was strictly forbidden!). George resolutely worked alone – no assistants, no power tools, only mallets and chisels and cassettes of classical music and operatic arias for company – but the confluence between their work speaks to a shared vision. We are delighted to include in this selection a painting by Eileen alongside a drawing of George’s, both made at their beloved Isle of Purbeck, where they had holidayed (and found inspiration, in the fields, quarries and shore) every year since the late 1930s. Seen side by side, these works could almost be by the same hand. George’s drawings, mainly of the rock formations of the coast that were the source of his material, whilst studies in sculptural form, have a painter’s confident flow: equally, Eileen’s paintings, whilst more concerned with the wider landscape, have a certain sculptural feel to their construction, even though, in the end, they concern themselves more with colour and abstract form, in the manner of Ivon Hitchens or Patrick Heron, both of whom she admired. The last few years have seen something of a revival in interest in George Kennethson’s work. After all, this is an artist whose work sits very comfortably – and beautifully – in Britain’s best small museum, Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, alongside Constantin Brancusi and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. There are now two monographs on the artist, the most recent written by the eminent critic Richard Cork. Eileen Guthrie’s work, on the other hand, still remains something of a secret, her last public exhibitions being held almost 40 years ago now. We hope that this brief glimpse will be the beginning of her revival, as well as a testament an artistic partnership that was very much of its time, yet resonates with beauty today.

§ George Kennethson (British 1910-1994) Waves initialled (lower right), pencil, ink and wash on blue paperDimensions:18cm x 22cm (7 1/8in x 8 5/8in)Provenance:ProvenanceThe Estate of the Artist.Note: George Kennethson (or Arthur Mackenzie as he was, Kennethson being the name he adopted in the early 1970s in order to separate his artistic practice from his role as the art master at Oundle School) met Eileen Guthrie in 1931 at the Royal Academy Schools in London. Intriguingly both were painting students, although in George’s case, the teaching at the still very academic Academy mainly had the effect of turning him into a sculptor, something he was already considering by his final year when the pair of them met [although one of his sons recalls Kennethson generously saying that the reason he became a sculptor was that Eileen was by far the better painter].George had come from a cultured, literary family. Eileen’s father and grandfather were architects and her mother was an accomplished pianist, who had studied at the Royal College of Music [Eileen herself had been taught piano by Gustav Holst when she was young]. And so, like many of their circle, Eileen and George were left-wing in their politics, interested in all things avant-garde in art, music and literature, and looked to Paris for inspiration. As young artists they both revered Cezanne. On their first trip together to the French capital, George tracked down the work of sculptors Maillol, Zadkine and Brancusi. And Eileen no doubt sought out the work of Bonnard, whose influence, both in composition and technique, can be traced in her work. They returned, in 1937, where they saw Picasso’s recently completed Guernica, which moved them both, artistically and politically. Like many artists of their generation, their lives and careers were profoundly affected by the Second World War. The Kennethsons were committed pacifists. A year before war broke out, they had moved to the quiet Berkshire village of Uffington, watched over by its ancient, curiously abstract White Horse, cut into the chalk of the nearby Downs, and so in away had already withdrawn from the political storm of the late 30s. The local villagers had no issues with the Kennethsons’ avowed pacifism: they were artists, after all, so they expected them to be different. Whilst they passed the war in rural seclusion, conflict does seep into Kennethson’s sculpture, such as sculptures of travellers, with staffs and backpacks, or men carrying mattresses down to the local forge – images glimpsed out of the studio window, but now transformed into a moving response to the refugees that war inevitably creates. The couple took in both evacuees from the Blitz and the occasional European refugee (and much later in the 1980s, Kennethson returned to this theme as a response to the migrations forced by famine in Ethiopia). But more than this, the War and its aftermath led to little opportunity for artists to sell their work and therefore live by their art – something that was particularly acute for the Kennethsons, who by the late 1940s had five young boys to feed. Art historians have often been critical of British artists ‘retreating’ into teaching or commercial work, whilst their counterparts in America were splashing newly made paint across acres of pristine canvas and changing the direction of modern art forever, and yet this ignores the pressures on British artists, facing a public that was already relatively indifferent to modern art already and which now was broke.It was at this point that Eileen turned her hand to making prints for textiles. She did so with incredible success – artistically at least, as there was almost as little money for interiors and design in post-war Britain as there was for at. Eileen did, however, sell her ‘Flockhart Fabrics’ range – named after her Scottish grandfather - at Primavera, a leading interiors shop on Sloane Street, as well as to family and friends. Their neighbour in Uffington, John Betjeman, also helped them to find stockists, and Eileen’s twin sister Joan would open her London flat to showcase the designs. Lucienne Day, too, introduced Eileen to Amersham Prints, contractors to the government, and her design Bird and Basket was used in 1954 to furnish the Morag Mhor, the first all-aluminium yacht in the country.George lent a hand too, on the production side, contributing to designs, working on the lino-blocks and silkscreens and helping Eileen with the considerable manual work of printing the fabrics by hand. The prints are deceptively simple, strong and sculptural, whilst retaining the required elegance and beauty. The line that one sees in her gouaches and oils find an easy home amongst the repeats of fabric design and motifs that infuse George’s sculpture – birds, leaves, architectonic flower forms – are abstracted from her landscape painting.The family moved to Oundle in 1954, to a house with a large former malting attached, which made for good, if draughty, studios. George would have been surrounded by Eileen’s fabrics – at the long settle by the kitchen table or on one of the armchairs where he would read and draw- before heading out to his studio to carve equally simple forms, with soft curves and sharp edges, into stone and alabaster, so perhaps Eileen’s influence on George’s work shouldn’t be under-estimated. Meeting her late in her life – a decade after George’s death – she would walk amongst the sculptures, laid out on plinths in a cavernous Victorian former malting attached to their house, and place her hands intuitively on every undercut and turn (the wearing of rings was strictly forbidden!). George resolutely worked alone – no assistants, no power tools, only mallets and chisels and cassettes of classical music and operatic arias for company – but the confluence between their work speaks to a shared vision. We are delighted to include in this selection a painting by Eileen alongside a drawing of George’s, both made at their beloved Isle of Purbeck, where they had holidayed (and found inspiration, in the fields, quarries and shore) every year since the late 1930s. Seen side by side, these works could almost be by the same hand. George’s drawings, mainly of the rock formations of the coast that were the source of his material, whilst studies in sculptural form, have a painter’s confident flow: equally, Eileen’s paintings, whilst more concerned with the wider landscape, have a certain sculptural feel to their construction, even though, in the end, they concern themselves more with colour and abstract form, in the manner of Ivon Hitchens or Patrick Heron, both of whom she admired. The last few years have seen something of a revival in interest in George Kennethson’s work. After all, this is an artist whose work sits very comfortably – and beautifully – in Britain’s best small museum, Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, alongside Constantin Brancusi and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. There are now two monographs on the artist, the most recent written by the eminent critic Richard Cork. Eileen Guthrie’s work, on the other hand, still remains something of a secret, her last public exhibitions being held almost 40 years ago now. We hope that this brief glimpse will be the beginning of her revival, as well as a testament an artistic partnership that was very much of its time, yet resonates with beauty today.

§ George Kennethson (British 1910-1994) Father and Child, 1960s English alabasterDimensions:45.7cm high, 33cm wide, 25.5cm deep (18in high, 13in wide, 10in deep)Provenance:ProvenanceThe Estate of the Artist.Note: George Kennethson (or Arthur Mackenzie as he was, Kennethson being the name he adopted in the early 1970s in order to separate his artistic practice from his role as the art master at Oundle School) met Eileen Guthrie in 1931 at the Royal Academy Schools in London. Intriguingly both were painting students, although in George’s case, the teaching at the still very academic Academy mainly had the effect of turning him into a sculptor, something he was already considering by his final year when the pair of them met [although one of his sons recalls Kennethson generously saying that the reason he became a sculptor was that Eileen was by far the better painter].George had come from a cultured, literary family. Eileen’s father and grandfather were architects and her mother was an accomplished pianist, who had studied at the Royal College of Music [Eileen herself had been taught piano by Gustav Holst when she was young]. And so, like many of their circle, Eileen and George were left-wing in their politics, interested in all things avant-garde in art, music and literature, and looked to Paris for inspiration. As young artists they both revered Cezanne. On their first trip together to the French capital, George tracked down the work of sculptors Maillol, Zadkine and Brancusi. And Eileen no doubt sought out the work of Bonnard, whose influence, both in composition and technique, can be traced in her work. They returned, in 1937, where they saw Picasso’s recently completed Guernica, which moved them both, artistically and politically. Like many artists of their generation, their lives and careers were profoundly affected by the Second World War. The Kennethsons were committed pacifists. A year before war broke out, they had moved to the quiet Berkshire village of Uffington, watched over by its ancient, curiously abstract White Horse, cut into the chalk of the nearby Downs, and so in away had already withdrawn from the political storm of the late 30s. The local villagers had no issues with the Kennethsons’ avowed pacifism: they were artists, after all, so they expected them to be different. Whilst they passed the war in rural seclusion, conflict does seep into Kennethson’s sculpture, such as sculptures of travellers, with staffs and backpacks, or men carrying mattresses down to the local forge – images glimpsed out of the studio window, but now transformed into a moving response to the refugees that war inevitably creates. The couple took in both evacuees from the Blitz and the occasional European refugee (and much later in the 1980s, Kennethson returned to this theme as a response to the migrations forced by famine in Ethiopia). But more than this, the War and its aftermath led to little opportunity for artists to sell their work and therefore live by their art – something that was particularly acute for the Kennethsons, who by the late 1940s had five young boys to feed. Art historians have often been critical of British artists ‘retreating’ into teaching or commercial work, whilst their counterparts in America were splashing newly made paint across acres of pristine canvas and changing the direction of modern art forever, and yet this ignores the pressures on British artists, facing a public that was already relatively indifferent to modern art already and which now was broke.It was at this point that Eileen turned her hand to making prints for textiles. She did so with incredible success – artistically at least, as there was almost as little money for interiors and design in post-war Britain as there was for at. Eileen did, however, sell her ‘Flockhart Fabrics’ range – named after her Scottish grandfather - at Primavera, a leading interiors shop on Sloane Street, as well as to family and friends. Their neighbour in Uffington, John Betjeman, also helped them to find stockists, and Eileen’s twin sister Joan would open her London flat to showcase the designs. Lucienne Day, too, introduced Eileen to Amersham Prints, contractors to the government, and her design Bird and Basket was used in 1954 to furnish the Morag Mhor, the first all-aluminium yacht in the country.George lent a hand too, on the production side, contributing to designs, working on the lino-blocks and silkscreens and helping Eileen with the considerable manual work of printing the fabrics by hand. The prints are deceptively simple, strong and sculptural, whilst retaining the required elegance and beauty. The line that one sees in her gouaches and oils find an easy home amongst the repeats of fabric design and motifs that infuse George’s sculpture – birds, leaves, architectonic flower forms – are abstracted from her landscape painting.The family moved to Oundle in 1954, to a house with a large former malting attached, which made for good, if draughty, studios. George would have been surrounded by Eileen’s fabrics – at the long settle by the kitchen table or on one of the armchairs where he would read and draw- before heading out to his studio to carve equally simple forms, with soft curves and sharp edges, into stone and alabaster, so perhaps Eileen’s influence on George’s work shouldn’t be under-estimated. Meeting her late in her life – a decade after George’s death – she would walk amongst the sculptures, laid out on plinths in a cavernous Victorian former malting attached to their house, and place her hands intuitively on every undercut and turn (the wearing of rings was strictly forbidden!). George resolutely worked alone – no assistants, no power tools, only mallets and chisels and cassettes of classical music and operatic arias for company – but the confluence between their work speaks to a shared vision. We are delighted to include in this selection a painting by Eileen alongside a drawing of George’s, both made at their beloved Isle of Purbeck, where they had holidayed (and found inspiration, in the fields, quarries and shore) every year since the late 1930s. Seen side by side, these works could almost be by the same hand. George’s drawings, mainly of the rock formations of the coast that were the source of his material, whilst studies in sculptural form, have a painter’s confident flow: equally, Eileen’s paintings, whilst more concerned with the wider landscape, have a certain sculptural feel to their construction, even though, in the end, they concern themselves more with colour and abstract form, in the manner of Ivon Hitchens or Patrick Heron, both of whom she admired. The last few years have seen something of a revival in interest in George Kennethson’s work. After all, this is an artist whose work sits very comfortably – and beautifully – in Britain’s best small museum, Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, alongside Constantin Brancusi and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. There are now two monographs on the artist, the most recent written by the eminent critic Richard Cork. Eileen Guthrie’s work, on the other hand, still remains something of a secret, her last public exhibitions being held almost 40 years ago now. We hope that this brief glimpse will be the beginning of her revival, as well as a testament an artistic partnership that was very much of its time, yet resonates with beauty today.

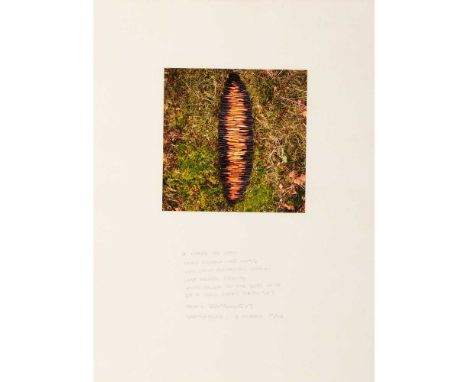

§ Andy Goldsworthy (British 1956-) Series of Seven Works, 1987-94 each inscribed, signed and dated in pencil, 6 c-prints and one work with traces of snow and dirt on paper, comprising:STONEWOOD SCAUR / ANDY GOLDSWORTHY / AUTUMN '87 and inscribed with poem, 20cm x 26cm (framed 72.5cm x 52.5cm);Slate, midday / collected locally / left over from roof repairs / lived under by many people / protecting the oak – burnt at its base – limbs sawn off / a partnership / STONEWOOD SCAUR / ANDY GOLDSWORTHY / SUMMER 88, each image 19cm x 12.5cm (framed 72cm x 52.5cm);The wall / Stonework by Joe Smith of Crocket**** / Winter 88/89 / STONEWOOD / ANDY GOLDSWORTHY, 25cm x 16.5cm (framed 72.5cm x 52.5cm);A MONTH OF RAIN / DEEP GREEN WET MOSS / UPROOTED BROKEN STACKS / LAST YEARS GROWTH / MOSS COLOUR IN THE SOFT LIGHT / OF A DULL GREY HEAVY SKY / ANDY GOLDSWORTHY / STONEWOOD/ 5 MARCH 1990, 18.5cm x 19cm (framed 72cm x 52cm);SNOW AND EARTH / STONEWOOD / ANDY GOLDSWORTHY 1991, traces of snow and dirt on paper, 51cm x 38cm (framed 72.5cm x 52.5cm);THE WALL / SUMMER 1993 / ANDY GOLDSWORTHY, 19cm x 23.5cm (framed 68cm x 53cm);TREE/ STICK / SNOW / STONEWOOD / ANDY GOLDSWORTHY 10 JAN 94, 23.5cm x 16cm (framed 68cm x 53cm)Dimensions:variable dimensionsProvenance:ProvenancePrivate Collection, Scotland. In 1987 the present owners' family gave financial support to Andy Goldsworthy's Stone Wood Plot Fund. In return the Artist supplied seven works (in editions of no more than 10) between 1987 and 1994.

§ Breon O'Casey (British 1928-2011) Boat, 1999 signed and dated in pencil in margin (lower right), numbered 11/15 (lower left), linocut on paperDimensions:45cm x 44cm (17 3/4in x 17 3/8in)Provenance:ProvenancePrivate Collection, Scotland.Note: ‘Breon O’Casey is a man for all seasons. He thinks and feels with his hands and moves with apparent ease from two-dimensional to three-dimensional activities, from one medium to another, without losing the artistic integrity of his intent. Breon O’Casey’s sensitive observations of life, art and nature inform his rich personal, visual language and beautifully balanced prose. His respect for his immediate environment and for tradition have enabled him to move forward with a confident, quiet ease, creating a refreshingly honest approach to art. He is an artist who is prepared to wait for the right shape, for the right brushstroke or the perfectly chosen word to express his meaning’. (Peter Murray (1)) Breon O’Casey was a true polymath and was possibly unique in the combination of skills he possessed over so many mediums in a single career. He was a painter, printmaker, weaver, sculptor and jewellery maker and it is hard to think of any other contemporary artist and maker who was so broadly talented. Son of the playwright Sean O’Casey (1880-1964), Breon spent most of his career in Cornwall, where he was closely associated with many of the painters, potters and sculptors of the St Ives movement. He arrived in the coastal town in the 1959 and served artistic apprenticeships under sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Denis Mitchell, and was friends with leading artists such as Peter Lanyon, John Wells and Tony O’Malley. In 1999 O’Casey recalled: ‘One day, watching television, some time in the late fifties, I saw a film about Alfred Wallis…the film incidentally showed St Ives and the studios of the artists living there. I realised it was the place for me. I owned a small orange Ford van. I packed the van and went. St Ives! In those days it was still a working fishing port, with tourism and artists tolerated, but kindly tolerated. Coming from Torquay, where I had felt like a rhinoceros walking along the streets, the relief of mingling with other crazy artists was enormous…I felt secure and there was a sort of electricity in the air.’ (2) O’Casey’s abstract style was poetic and focussed on discovering the simplicity of objects and forms. For him there was ‘nothing new under the sun, but an infinity of arrangements’ and when asked about objects that captivated him it was ‘not the wood, not the tree, but the leaf; not the distant view, but the hedge; not the mountain, but the stone’. He would return to geometric motifs and natural forms again and again throughout his career and considered himself a ‘traditional innovator’, fascinated by ancient, primitive and non-western art, but imbuing it with his own poetic sensibilities and discoveries through all the creative channels he explored. Although often overshadowed by his St Ives contemporaries, O’Casey’s legacy, talents and unique skills are now being reassessed, and greater importance given to his accomplishments beyond narrow and interlocked art circles. We are delighted to bring this collection of his work together to showcase many of the aspects of O’Casey’s prodigious artistic output, and to celebrate his significance as a true renaissance figure of British 20th-century art and craft. 1 / Peter Murray quoted in Sarah Coulson and Sophie Bowness, Breon O’Casey: An Anthology of his Writings, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, 2005, p.32 / Breon O’Casey quoted in Brian Fallon and Breon O’Casey, Breon O’Casey¸ Scolar Press, Aldershot, 1999, p.48.

-

400830 item(s)/page

![A Lot of three 9ct gold and gem stone rings. [13grams]](https://cdn.globalauctionplatform.com/639648c1-8f4f-44b4-997c-afeb00d527a6/40703f68-a7c1-46fc-b4aa-afeb0127d2d3/468x382.jpg)