We found 216136 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 216136 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

216136 item(s)/page

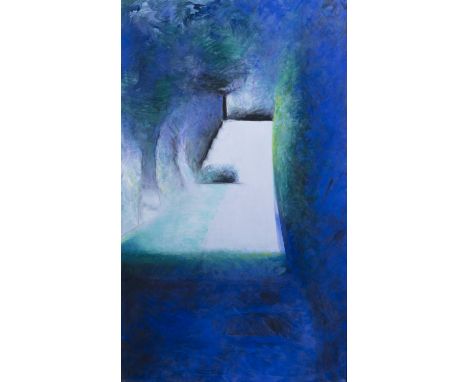

Anne Madden (b.1932)Chemins Éclairs (1988)Triptych, Oil on canvas, 195 x 339cm (76¾ x 133½)Signed, inscribed and dated 1988 on versoExhibited: Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris 1989; Kerlin Gallery, Dublin 1990; RHA Gallagher Gallery, Dublin 1991; Limerick City Gallery of Art 1991; Anne Madden - A Retrospective ExhibitionProvenance: Collection of Noeleen and Vincent Ferguson; Private Collection, IrelandLiterature: Anne Madden - A Retrospective Exhibition with Introductory Essay by Aiden Dunne, Dublin 1991, Illustrated p. 63, Catalogue No. 50 The illuminated paths in Anne Madden’s triptych are, figuratively, paths of light, and they are depictions of an actual path, aglow amidst the enveloping shade of the garden: the path to her studio. The studio, which she shared with her partner Louis le Brocquy, was built in 1962 at their home, Les Combes, in the foothills of the Alps above Nice. Les Combes, and specifically the studio, was the centre of their daily life for close on three decades - they returned to settle in Ireland in 2000.In 1984, Madden was devastated by the sudden death of her younger, much loved brother, Jeremy Madden Simpson. Over the following years, she found herself adrift in mourning him. She likened it to being confined in a dark room, and eventually felt that she was in exile from the studio; painting held no appeal. Talking to Samuel Beckett in 1987, she explained her predicament. He later wrote to her saying that she must deal with the darkness, express it, rather than trying to elude it. She took his words to heart, compiling a volume of Jeremy’s writings - and trying to find her way back to the studio.This process engendered a number of paintings partly built around the metaphorical opposition of light and dark. Light was the possibility of life, hope, creativity, and darkness was the state of being cut off from all of those things. The studio is not just an atelier, a workshop, it is the centre of life, a generative space. The illuminated path is a way out of darkness, back to life in all its contingency and promise.Madden was born in Chile. Her father was Irish, her mother Anglo-Chilean, and they moved to England when she was about four. Ireland became important as she visited her father’s relations in Co. Clare with him, discovering and spending time in the Burren, thereafter a landscape of central imaginative importance to her. In 1950, she seriously injured her spine in a riding accident, necessitating serious surgery. When she and Louis le Brocquy (they married late in the decade) moved to France, it was largely because the climate was more amenable to healing her bones.From the 1950s onwards, Madden’s exceptionally ambitious paintings fuse elements of the extraordinary Burren environment, its vast skies, limestone pavement and stone monuments, with the techniques and scale of American abstraction. Gradually her range of reference diversified to encompass the city of Pompeii, some classical mythic narratives, Odyssean voyages and the Aurora borealis. If mortality and mourning have been consistent underlying concerns, so too is a sense of creative possibility and wonder, and a rapt appreciation of beauty.

Rowan Gillespie (b.1953)Peace IIBronze, 78cm high (30¾'')Signed, inscribed and dated 1999 underneath the baseFemale figures are quite prominent in Gillespie’s work, with his depiction of the body often acting as a celebration of female liberty and the vitality of life. They are not treated in the same way as a classical sculpture in which the female form was often depicted as an object of beauty. Instead Gillespie strives to create thoughtful expressions of the free-spirited and independent nature of modern women. Freedom is a constant thread in Gillespie’s work, something his sculptures seem to always be striving towards, whether they are scaling the side of a building, Aspiration (1995) or perched on a window ledge, Birdy (1997). His figures seem to affect an act of defiance in the face of gravity. While Gillespie’s sculptures are often struggling under the weight, literal and metaphorical, of the base, elemental forces of life there is also a lightness, a joy found within his depictions of the human form. There is a visual link between the outstretched arms in Peace II and the Blackrock Dolmen (1987), although on this occasion the figures are not supporting the heavy weight of the stone. Instead with their arms outstretched, reaching upwards towards an imaginary light, one is reminded of his respective large-scale public commissions in Italy and Dublin, L’Eta della donna (2009) and The Age of Freedom (1992). On both occasions the figures stand, similar to the present work, naked, offering some form of thanksgiving to the sun. The two figures in Peace II, seem to grow upwards from the same source, their bodies intertwined with one another. It is an expression of gratitude, a gesture of sublimation and hope. While he is known for his emotionally arresting Famine memorial, here there is a delicacy to the treatment of the material which seems to hark back to his earlier investigations into the human form. The finish of the bronze in this work is the antithesis of the cracking, raw patinas of his Famine figures. However, once again he has created a visual as well as physical connection to the raised arms of his Jubilant Man (2007) sculpture in Ireland’s Park, Toronto, who upon safe arrival in Canada is utterly overcome with emotion.Niamh Corcoran, September 2019

-

216136 item(s)/page