We found 314783 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 314783 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

314783 item(s)/page

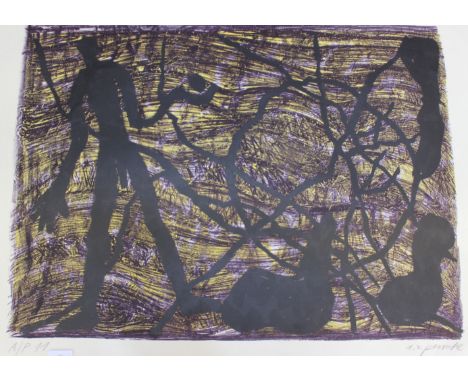

[§] MARTIN BOYCE (SCOTTISH B.1967) NO BRILLIANTLY COLOURED BIRDS Signed and dated '09 in pencil to margin, numbered 22/40, screenprint, unframed 74cm x 102 cm (29in x 40in) Note: Martin Boyce developed this large scale print as part of his No Reflections installation for the Scottish Pavilion of the 2009 Venice Biennale. Continuing Boyce's interest in the ‘collapse of nature and architecture’ and interior and exterior forms, this print references the empty wooden interior of the artist's bird box sculpture in the vacated Italian Palazzo; the holes in which simultaneously suggest the form of a head or mask. During the development of this project Boyce drew from a short text he had written with an abandoned zoo in mind: ‘warm dry stone and palm leaves, no elephants, no giraffes, no penguins, no brilliantly coloured birds…’. This language of an abandoned garden is continued with the text 'No Brilliantly Coloured Birds' that tumbles out across the image. The form of the text stems from a central structural motif that forms a core of much of Boyce’s work. This motif is derived from an early black and white photograph of four geometric concrete trees sculpted by Joel and Jan Martel in 1925. (Text courtesy of Dundee Contemporary Arts)

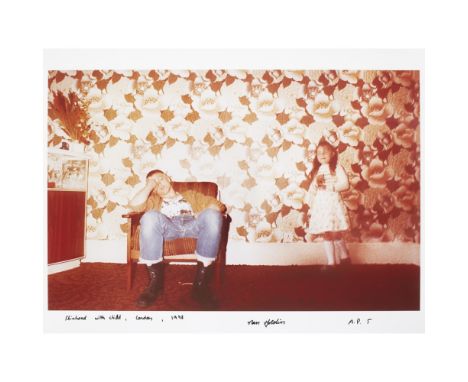

NAN GOLDIN (AMERICAN B.1953) SKINHEAD WITH CHILD, LONDON, 1978 C-print, artist's proof, signed and inscribed, unframed 45cm x 60cm (17.75in x 23.5in)Nan Goldin‘For me taking a picture is a way of touching somebody—it’s a caress. I’m looking with a warm eye, not a cold eye. I’m not analysing what’s going on—I get inspired to take a picture by the beauty and vulnerability of my friends.’It is difficult to imagine in 2018, when everyone is an amateur photographer, a smart phone with built-in camera feels like an extension of self to most people and Instagram, the image-based social media platform for sharing ‘snapshots’ of your life is rapidly gaining popularity, how radical Nan Goldin’s work was when she first unleashed her vision and aesthetic on the art world in 1973.The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is the over-arching name for a body of work created by Goldin depicting her social circle and their life through the 1970s and 80s. Created over many years, it was originally presented by the artist as a slideshow set to music, totalling approx. 700 images in a period of around 45 minutes, before being published as a book in 1986. It has more recently been re-presented in its original slideshow format in a selection of art institutions. Both artworks offered in this auction, The Hug and Skinhead with Child, London, 1978 are from this body of photography.With her captivating and immediate ‘snapshot’ style, Nan Goldin’s photography creates an intersection of autobiographical detail and documentary storytelling, as she honestly captures her friends as they live their lives, creating a body of work that is at once radical, intimate, personal, joyful and moving. Her circle of friends, subsumed as they are in the New York counter-culture of the 1970s and 80s, are shown in their beds, kitchens and living rooms, embracing, dancing, kissing, dressing, undressing and shooting up with a casual immediacy and frankness that can be disconcerting for the viewer.Yet Goldin was not a casual observer of this lifestyle, and was instead a close friend of all the people depicted, living with them and participating in this hedonistic lifestyle. She called these close friends her family, describing them as ‘bonded not by blood, but by a similar morality, the need to live fully and for the moment.’ She said of her artistic intentions, ‘I know how to make someone look beautiful. And I’ll never photograph anyone I don’t know. You have to know the person to really be able to photograph them. But I never show pictures of my friends if they don’t want me to. My drawers are full of great photographs that I won’t show because the person asked me not to.’ The sense of the work as confessional and uncompromising, making private acts, spaces and moments public is only strengthened by the artist’s commitment to self-portraits. She is as unflinching an observer of herself as of others, and her gaze is always one of love and connection, rather than interrogation or judgement. By her own admission, her photography is ‘the diary I let people read.’Goldin’s style and approach always stemmed from her life and circumstances, from capturing those closest to her, to working with artificial light as that was how she saw and experienced her life at that time, living almost nocturnally in central New York, and utilising slides and getting her prints developed in the chemists as she had no access to a darkroom. In The Hug, we get a real sense of Goldin’s approach, the camera and photographer as observer of an intimate moment, of human affection and connection, yet also with a potentially darker edge of vulnerability and power; it only takes a single male arm to completely encircle the woman’s body. The complexity of human connection and our way of relating to each other is reinforced in the artist’s handwritten inscription, ‘sometimes it hurts, sometimes it doesn’t, you know.’ While Skinhead and Child, London, 1978, demonstrates Goldin’s keen visual eye, capturing this odd juxtaposition of figures with its surprising compositional balance, and nods to the luck and circumstance inherent in the medium of photography, of hundreds of photographs taken, this is one of the images that delivers, the light and patterns giving an strikingly eerie and ghostly effect.In 2018, Goldin’s striking photographs continue to attract different meanings and foster new connections, as we read and experience them in relation to current events and attitudes. Goldin herself has said, ‘I always thought if I photographed anyone or anything enough, I would never lose the person, I would never lose the memory, I would never lose the place. But the pictures show me how much I've lost.’ And we can feel that even more acutely now, as we realise that many of the subjects, the friends and adopted family of the artist, have not survived, they are a generation lost to drugs, AIDS and suicide and although they have been captured in these specific moments, we do not know the entirety of their complicated story.

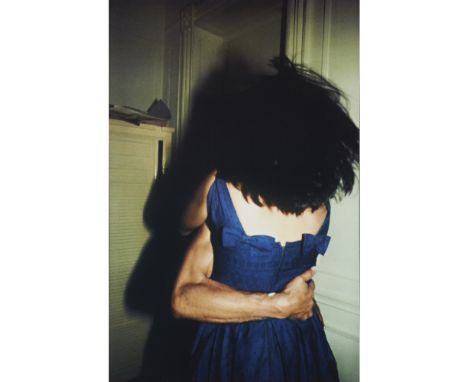

NAN GOLDIN (AMERICAN B.1953) THE HUG C-print mounted on Sintra foam-board, artist's proof, signed and inscribed verso 'Sometime it hurts, sometimes it don't, you know N.' 39cm x 59.5cm (15.25in x 23.5in)Nan Goldin‘For me taking a picture is a way of touching somebody—it’s a caress. I’m looking with a warm eye, not a cold eye. I’m not analysing what’s going on—I get inspired to take a picture by the beauty and vulnerability of my friends.’It is difficult to imagine in 2018, when everyone is an amateur photographer, a smart phone with built-in camera feels like an extension of self to most people and Instagram, the image-based social media platform for sharing ‘snapshots’ of your life is rapidly gaining popularity, how radical Nan Goldin’s work was when she first unleashed her vision and aesthetic on the art world in 1973.The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is the over-arching name for a body of work created by Goldin depicting her social circle and their life through the 1970s and 80s. Created over many years, it was originally presented by the artist as a slideshow set to music, totalling approx. 700 images in a period of around 45 minutes, before being published as a book in 1986. It has more recently been re-presented in its original slideshow format in a selection of art institutions. Both artworks offered in this auction, The Hug and Skinhead with Child, London, 1978 are from this body of photography.With her captivating and immediate ‘snapshot’ style, Nan Goldin’s photography creates an intersection of autobiographical detail and documentary storytelling, as she honestly captures her friends as they live their lives, creating a body of work that is at once radical, intimate, personal, joyful and moving. Her circle of friends, subsumed as they are in the New York counter-culture of the 1970s and 80s, are shown in their beds, kitchens and living rooms, embracing, dancing, kissing, dressing, undressing and shooting up with a casual immediacy and frankness that can be disconcerting for the viewer.Yet Goldin was not a casual observer of this lifestyle, and was instead a close friend of all the people depicted, living with them and participating in this hedonistic lifestyle. She called these close friends her family, describing them as ‘bonded not by blood, but by a similar morality, the need to live fully and for the moment.’ She said of her artistic intentions, ‘I know how to make someone look beautiful. And I’ll never photograph anyone I don’t know. You have to know the person to really be able to photograph them. But I never show pictures of my friends if they don’t want me to. My drawers are full of great photographs that I won’t show because the person asked me not to.’ The sense of the work as confessional and uncompromising, making private acts, spaces and moments public is only strengthened by the artist’s commitment to self-portraits. She is as unflinching an observer of herself as of others, and her gaze is always one of love and connection, rather than interrogation or judgement. By her own admission, her photography is ‘the diary I let people read.’Goldin’s style and approach always stemmed from her life and circumstances, from capturing those closest to her, to working with artificial light as that was how she saw and experienced her life at that time, living almost nocturnally in central New York, and utilising slides and getting her prints developed in the chemists as she had no access to a darkroom. In The Hug, we get a real sense of Goldin’s approach, the camera and photographer as observer of an intimate moment, of human affection and connection, yet also with a potentially darker edge of vulnerability and power; it only takes a single male arm to completely encircle the woman’s body. The complexity of human connection and our way of relating to each other is reinforced in the artist’s handwritten inscription, ‘sometimes it hurts, sometimes it doesn’t, you know.’ While Skinhead and Child, London, 1978, demonstrates Goldin’s keen visual eye, capturing this odd juxtaposition of figures with its surprising compositional balance, and nods to the luck and circumstance inherent in the medium of photography, of hundreds of photographs taken, this is one of the images that delivers, the light and patterns giving an strikingly eerie and ghostly effect.In 2018, Goldin’s striking photographs continue to attract different meanings and foster new connections, as we read and experience them in relation to current events and attitudes. Goldin herself has said, ‘I always thought if I photographed anyone or anything enough, I would never lose the person, I would never lose the memory, I would never lose the place. But the pictures show me how much I've lost.’ And we can feel that even more acutely now, as we realise that many of the subjects, the friends and adopted family of the artist, have not survived, they are a generation lost to drugs, AIDS and suicide and although they have been captured in these specific moments, we do not know the entirety of their complicated story.

[§] SALVADOR DALI (SPANISH 1904-1989) AFTER 50 YEARS OF SURREALISM - 1974 The complete set of 12 etchings with handcolouring, from the English edition, with signed and numbered title page, each within an original paper folder with text by André Parinaud, all contained within original black linen-covered portfolio. Each etching signed and numbered 'A 56/195.' each etching 66cm x 50cm (26in x 19.75in)Salvador Dali, After 50 Years of Surrealism, 1974After 50 Years of Surrealism is a suite of twelve original drypoint etchings hand-coloured with watercolour paint and each contained in a folder with a corresponding text by art critic and writer André Parinaud. Surrealism, literally meaning ‘above reality’ sought to liberate the human mind from rational thought by celebrating the absurd and this portfolio leads the viewer through the memories and dreams of perhaps the most iconic of the movement’s painters: Salvador Dali. The portfolio’s combination of word and image seems a fitting commemoration of Surrealism which began as a literary movement, and is perhaps an homage to André Breton who published The Surrealist Manifesto fifty years earlier in 1924.The original etchings are each signed by Dali and showcase his renowned mastery of draftsmanship. Dali himself stated that ‘’Drawing is the honesty in art. There is no possibility of cheating. It is either good or bad’’ and the light washes of watercolour applied on top of these etchings leave room to appreciate just how good Dali’s draughtsmanship is. His linear compositions conjure dreamlike Dalinian creatures in such detail they almost appear to be observed from life while also managing to describe the baked plains and mountainous horizons of Dali’s beloved Catalonian landscape sometimes with a single flowing line. Dali’s choice of the medium of print reflect his desire to ‘‘incorporate surrealism into tradition’’ as he combines Surrealist landscapes dominated by iconic motifs such as gigantic shoes and spider legged elephants with the established tradition of etching.This portfolio was completed late into Dali’s artistic career and the symbolically charged scenes use Dali’s own memories as the source material highlighting his lifelong fascination with Sigmund Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams (1899) which identified the unconscious as a fertile site of repressed fantasies and emotions and which the Surrealists saw as a way of accessing the untapped creativity of the mind. The titles of the etchings refer to significant events in Dali’s life, both public and private, giving the portfolio an incredibly intimate feel. Gala’s Godly Back recreates Dali’s first sighting of Gala Éluard, his future wife and muse, on the beach in Cadaquès in 1929. The Great Inquisitor Expels the Saviour depicts a Pope hurling a flaming giraffe from a turret window, a humorous account of Dali’s infamous expulsion from the Surrealist circle in 1934 by Breton who was known as the ‘Pope of Surrealism’ due to his tendency to excommunicate artists from the movement.The corresponding texts by Parinaud complement each of the etchings by analysing their dreamlike iconography and often including insightful biographical anecdotes and quotes from Dali himself about the details of each event. In 1929 Breton stated that ‘’it is perhaps with Dali for the first time the windows of the mind are opened fully wide’’ and in the same way these etchings offer the viewer an insight into Dali’s deeply confessional yet delightfully surreal mind.

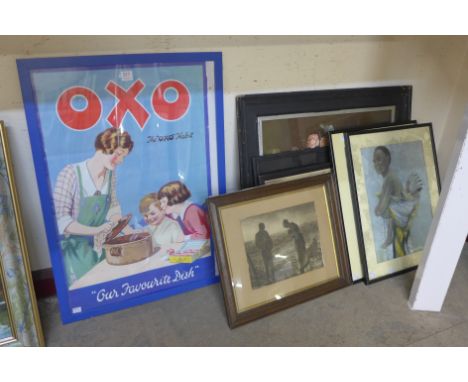

A Small Collection Of Framed Paintings And Prints three items in total, to include large oil on board depicting the apex of a waterfall, housed in gilt frame. Along with Edwardian photographic print of a young woman housed in period brushed gilt circular frame. Also, framed print after Joannes Van Noordt 'Boy Holding Hawk'.

-

314783 item(s)/page

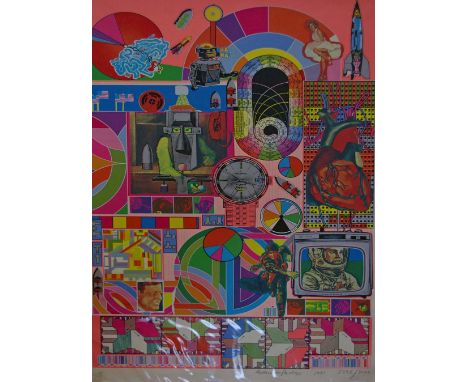

![[§] BRUCE MCLEAN (SCOTTISH B.1944) A NEW FRONT DOOR Signed and dated 1980 in pencil to margin, numbered 12/50, screenprint](https://cdn.globalauctionplatform.com/2cf487da-1f6e-4783-ab7b-a927009eaef2/1fec8866-40d7-408e-a2a3-c2988019f817/468x382.jpg)

![[§] MARTIN BOYCE (SCOTTISH B.1967) NO BRILLIANTLY COLOURED BIRDS Signed and dated '09 in pencil to margin, numbered 22/40,](https://cdn.globalauctionplatform.com/2cf487da-1f6e-4783-ab7b-a927009eaef2/6fa87d47-a2b4-425b-aafa-4655c8cfaaf6/468x382.jpg)

![[§] SALVADOR DALI (SPANISH 1904-1989) AFTER 50 YEARS OF SURREALISM - 1974 The complete set of 12 etchings with handcolo](https://cdn.globalauctionplatform.com/2cf487da-1f6e-4783-ab7b-a927009eaef2/a2fd0409-cae2-440f-abbd-2c68d0e55cf7/468x382.jpg)