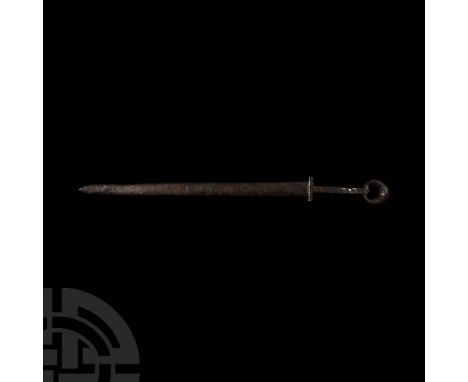

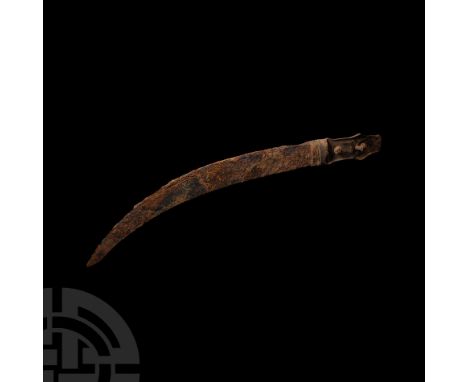

Circa 2nd-3rd century A.D. Featuring a distinctively shaped ring at the end of the grip, double-edged relatively short blade and a tapered tip. Cf. Miks, C., Studien zur Romischen Schwertbewaffnung in der Kaiserzeit, I-II Banden, Rahden, 2007, pls.46-51, for similar swords; also D'Amato, R., Arms and Armour of the Imperial Roman Soldier, London, 2009, p.88.376 grams, 58 cm (22 7/8 in.). Acquired 1990s-early 2000s. East Anglian private collection.Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D'Amato. This kind of sword - called by modern scholars as ringknaufschwert or ring-pommel sword - was firstly diffused amongst the auxiliary troops, probably Sarmatians and Germans, and then, during the 2nd century A.D., was also commonly used amongst the milites legionis and the officers. The shape of their blades is similar to the Pompey typology, but a slightly less acute angle characterises the passage from the blade to the short point. There were longer specimens like spatha, opening the transformation of the legionary gladius in the longer spatha specimens of the successive period, and also shorter specimens. An important dating element for earlier specimens is the sword from the Matrica grave, in Pannonia, dated exactly to 147 A.D. based on the other grave goods. Specimens of the second half of 2nd century A.D. are known from Wehringen and Geneva (180 A.D.). A specimen from Bosnia could be chronologically assigned to the same period, although such kind of swords became much more widespread for infantry and cavalry in later times. However, the importance of such swords has been recently associated with the rank of the provincial officers who used them, including miniature variations of such swords used as pendants as insignia badge of the staff of the Provincial governors. It was connected with the image of the sword and the dagger as a symbol of the Imperial power.

We found 1087795 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 1087795 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

1087795 item(s)/page

15th century A.D. Comprising a straight, flat triple fuller, double edged and tapering blade engraved with imperial orb sign, Passau wolf mark dated 15th century and 'DIGN LAGDIGNLA', with steel hilt comprising of down-turned quillons with ball finials and single ring outer defence, the bars of round section; matching inner defence bar with matching decoration to the quillons, spherical pommel rebound leather grip with original 'Turk's heads' to top and bottom but worn. 1.46 kg, 1.05 m (41 1/4 in.). Acquired from Military Swords Ltd, UK, 2017. The Kusmirek Collection, UK.Accompanied by a copy of an invoice. This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate no.203964.

1939-1979 A.D. With 'reef knot' loop and ring and silk ribbon. Obv: 25mm diameter hand enamelled central disc depicting the radiant standing lion guardant holding shamshir sword with red and green border set against the radiant four-pointed star backing. Rev: shaped with fixed suspension loop; with original blue hinged case of issue with crowned radiant lion emblem to upper lid and printed 'ARTHUS BERTRAND / PARIS' in two lines to inner silk lining of lid. Barac III, 111 (p.1062); see Younessi, Dr O. James, Orders, Decorations and Medals of the Empire of Iran - The Pahlavi Era, USA, 2016, pp.189-198 for details of this order and its badges.141 grams total, box 7.5 x 14 cm. (3 x 5 1/2 in.). Acquired by the vendors father on the UK art market, before 1990. The Order of Homayoun is also known as the Order of the August and was founded in 1939 to replace the earlier Order of the Lion and Sun (instituted 1808); the Order was issued in five degrees with the 5th class being designated Knight of the Order.

354-300 B.C. Obv: head of Athena right, eye in profile, wearing crested helmet with two olive leaves and scroll, and circular ear ring, retrograde South Arabian letter 'n' on cheek. Rev: AQE to right of owl standing right, head facing, olive spray and crescent in upper left field. BMC 5; Huth & Van Alfen SII.A; HGC 10, 720.5.11 grams. Property of a North London gentleman.

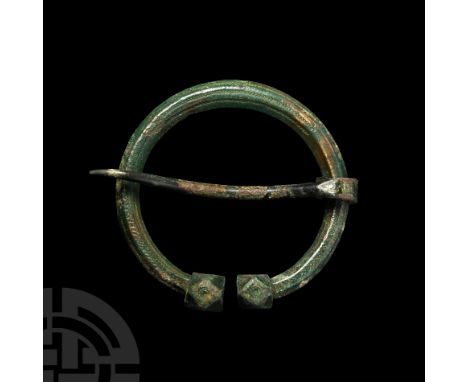

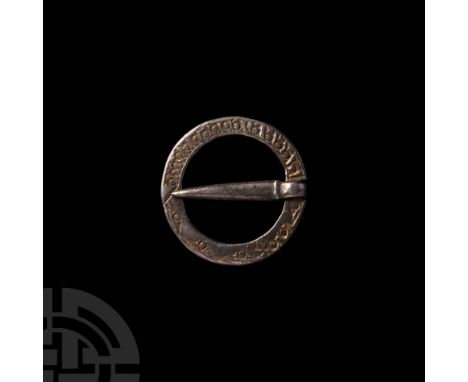

Circa 10th century A.D. Composed of a decoratively twisted tapering annular ring and a free-running tongue of tapering round-section form. Cf. annular brooches in Arbman, H., Birka I: Die Gräber, Uppsala, 1940, pl.46.7.34 grams, 33 mm (1 1/4 in.). Acquired on the London art market, 1980s-1990s.This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate no.202988. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

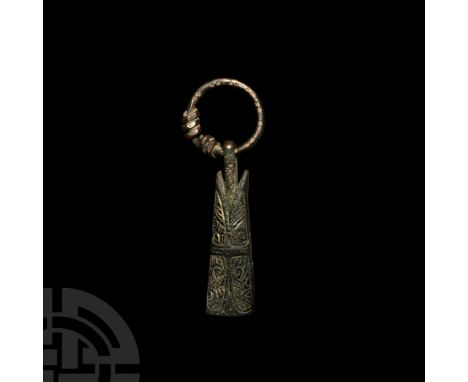

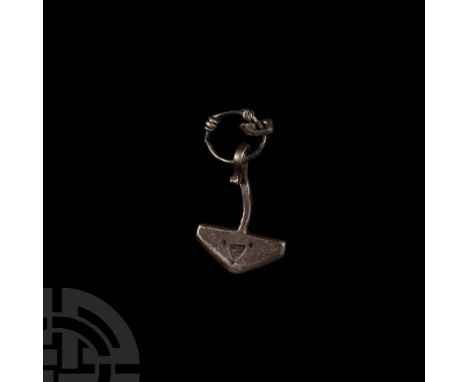

9th-10th century A.D. Composed of a tapering, round-section body with flat base and inverted triangular mouth holding a moveable bar, suspended on a ring with twisted wire coils and stamped with small circles repeated on the bar below; the fish body decorated with four panels of low-relief Mammen Style interlacing with remains of gilding; two circular piercings to each side of the body. Cf. MacGregor, A. et al., A Summary Catalogue of the Continental Archaeological Collections, Oxford, 1997, item 13.1, for similar.23.2 grams, 72 mm high (2 3/4 in.). Private collection formed in Europe in the 1980s. Ex Westminster collection, central London, UK. Originally produced as a necklace element, refashioned at an unspecified point in antiquity into a pendant, possibly as early as the 9th-10th century A.D. Pendants of this type were worn strung together in groups, the tapering profile allowing them to sit comfortably as a collar below the neck. They were often worn suspended between two zoomorphic brooches. This example has been taken from a necklace and mounted on a suspension ring for use as an amuletic pendant. [No Reserve]

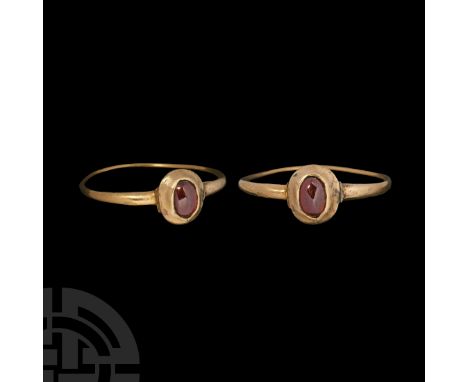

13th century A.D. Composed of a delicate hoop, carinated shoulders and biconical bezel, elliptical in plan with inset polished cabochon garnet. Cf. The V&A Museum, accession number 641-1871, for a similar ring set with a sapphire.1.86 grams, 25.44 mm overall, 19.84 mm internal diameter (approximate size British R 1/2, USA 8 3/4, Europe 19.38, Japan 18) (1 in.). Found while searching with a metal detector in Bossingham, Kent, UK, by Alan John Punyer on 14 September 2000.Disclaimed under the Treasure Act with reference no. M&ME 297. Accompanied by a copy of page 61 of the Treasure Annual Report 2000, where this ring is published as number 92.For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

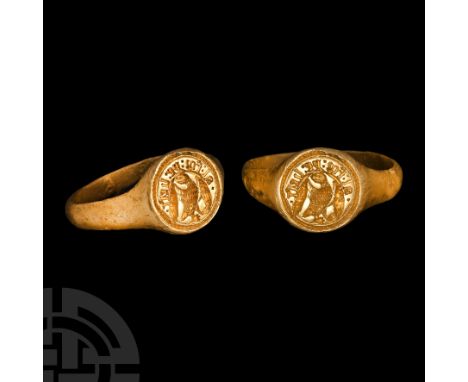

14th-15th century A.D. Gold hoop and discoid bezel with incuse ropework border; incuse image of a bird of prey perching with wings spread and head turned; blackletter incuse and reversed inscription in an arc above the bird's head and pinions '·al : for : ye : best ·' (all for the best); repair to hoop. Cf. Ward, A. et al., The Ring from Antiquity to the Twentieth Century, Thames and Hudson, London, 1981, types 164, 165. 'Gold Armorial Sheriff's Ring', Treasure Hunting Magazine, August 2022, p.13. 8.01 grams, 25.00 mm overall, 20.49 mm internal diameter (approximate size British V 1/2, USA 10 3/4, Europe 24.4, Japan 23) (1 in.). Found while searching with a metal detector near Roxwell, Essex, UK, by Albert Robert Taylor on 4th September 2021.Accompanied by a copy of the British Museum's Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) report no.ESS-CD68AE. Accompanied by a copy of the report for H M Coroner on find of potential treasure with reference no.2022 T920. Accompanied by a copy of a letter from the British Museum disclaiming the Crown's interest in the find. Accompanied by a copy of the Treasure Act receipt. Accompanied by copies of the relevant pages on an article about finding this ring in Treasure Hunting Magazine, August 2022, p.13. The ring's find location is close to an estate which was owned in the 14th century by the Skrene family and which included among their number a senior barrister and sergeant-at-law named William Skrene who was an Irish-born barrister and judge. The family name lives on to the present day at Roxwell with Skreens Park and for local road names nearby. Wiiliam spent his professional life in England, being appointed King's Serjeant and a judge of assize, as well as Chief Baron of the Irish Exchequer in 1395-7. In addition to the estate at Roxwell, he acquired various lands in Essex, including at Writtle, Great Finborough and Stanford Rivers. William died in 1419-20 and left sons and a daughter; his heir, also called William, married Alice Tyrrell, widow of Hamo Strange, and daughter of John Tyrrell, who was Speaker of the House of Commons of England for three terms. The exact combination of motto and crest or badge has eluded researches thus far. However, the ring was found near Roxwell, Essex, and evidently belonged to a person of some wealth and status given the quantity of gold used in its manufacture and the quality of the workmanship. The style of the ring is close in appearance to a number of early 15th century examples, which began to appear with the badge and motto rather than the full armorial bearings, so it is very possible that this is the personal signet ring of William Skrene, or possibly of his sons, William or Thomas. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

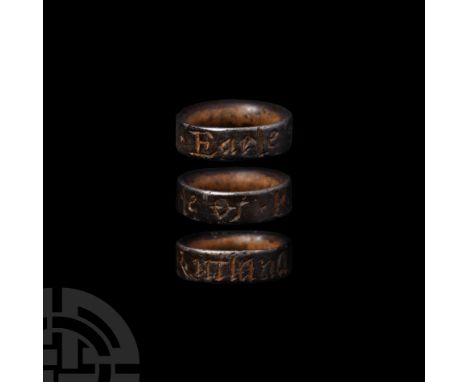

Circa 1440-1460 A.D. Or a leg ring inscribed '+Earle of Rutland' in derivative black letter script, for a female merlin or sparrow hawk (due to the youth of Edmund Plantagenet who died aged 17); the ring with a convex interior face.Lewis, M. and Richardson, I., Inscribed Vervels, Oxford, 2019; Type B listed on pp.87-8 where dated c.1450-c.1600, with the note that it was previously sold by Timeline Auctions 2 December 2011, lot 793. 0.56 grams, 8 mm (1/4 in.). Acquired in the 1960s. Ex Bursnall collection, Leicestershire, UK. From the collection of a North American gentleman. Unique and with links to royalty and the Wars of the Roses. Edmund Plantagenet, Earl of Rutland was executed after the Battle of Wakefield (probably by John Clifford) and was the son of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York (a great-grandson of Edward III, father of Edward IV and one of the most powerful English magnates during the Wars of the Roses between the Yorkists and Lancastrians). The first Earl of Rutland was Edmund Plantagenet (grandson of Edward III and executed following the Southampton Plot against Henry V), uncle to Richard. The Earldom of Rutland has historically been closely linked to the Duchy and House of York. For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

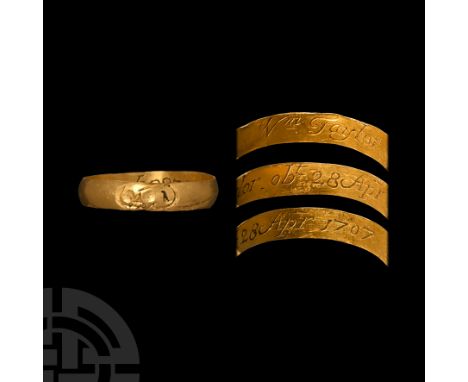

Dated 1707 A.D. Composed of a gently convex hoop engraved with a skull, the interior inscribed in cursive script: 'Wm Taylor obt 28 Apr 1707', followed by an unidentified maker's stamp 'TP'(?) within rectangular cartouche. Cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1542, for a similar skull on a ring of a similar date.2.54 grams, 21.03 mm overall, 19.34 mm internal diameter (approximate size British S, USA 9, Europe 20, Japan 19) (3/4 in.). Acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK.[No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

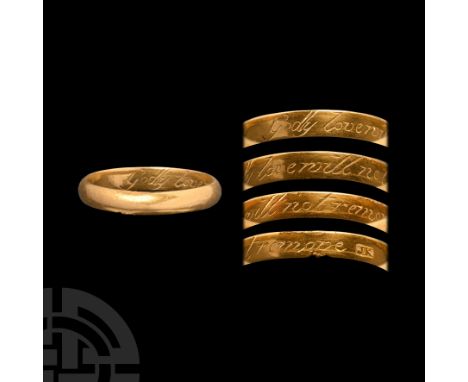

Circa 18th century A.D. The D-section hoop with plain exterior, the interior inscribed 'Godly love will not remove', followed by maker's mark 'JK' in a rectangular cartouche. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, p.43, for this inscription; cf. The British Museum, museum numbers AF.1252 and AF.1253, for this inscription on a ring dated 17th-18th century AD, and museum number AF.1315 for this maker's mark, believed active between 1755-1764, name unknown; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. SUSS-73E152, for a similar ring with this inscription, also stamped 'JK', dated 1700-1800, possibly the same maker's mark.4.17 grams, 21.73 mm overall, 18.94 mm internal diameter (approximate size British R, USA 8 1/2, Europe 18 3/4, Japan 18) (3/4 in.). Ex Albert Ward collection, 1974-1985. East Anglian private collection. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

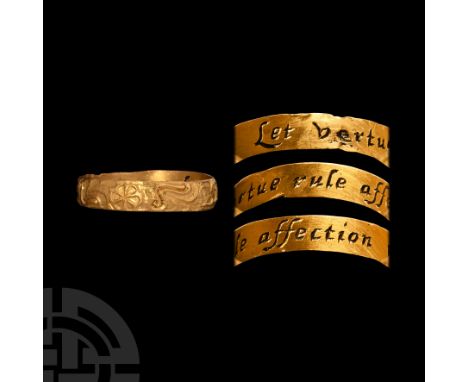

17th-18th century A.D. Composed of a chased exterior displaying flower heads and animals, the interior inscribed 'Let vertue rule affection' and filled with black enamel, followed by unidentified maker's stamp 'P' within a shield-shaped cartouche. Cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, record id. HAMP-CD6223, for another ring with this inscription and with an exterior design executed in similar style.1.36 grams, 17.09 mm overall, 15.59 mm internal diameter (approximate size British J, USA 4 3/4, Europe 8.69, Japan 8) (5/8 in.). Acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

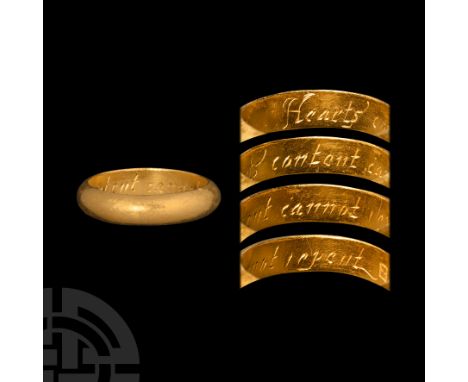

17th century A.D. Composed of a carinated outer face and inscription to interior in cursive script: 'Hearts content cannot repent' followed by a maker's stamp formed as florid a letter 'I' within a rectangular cartouche. Cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1266, for a ring with this inscription dated 17th century; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, record ids. WILT-AFE9A5, and GLO-D67CD3, for similar rings with very similar inscriptions dated 17th century; cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, 1931, p.46, for two very similar inscriptions.6.54 grams, 21.46 mm overall, 17.32 mm internal diameter (approximate size British N, USA 6 1/2, Europe 13.72, Japan 13) (7/8 in.). Acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

1650-1725 A.D. Composed of a gently carinated hoop, the interior inscribed in cursive script 'Love is the bond of pease'. Cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1339, for this inscription with slight spelling variation and for a similar plain exterior; cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, 1931, p.73, for this inscription with slight spelling variation; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, record id. SUSS-04EA22, for a similar style of ring also heavy at 7.43 grams.7.81 grams, 22.97 mm overall, 18.75 mm internal diameter (approximate size British R, USA 8 1/2, Europe 18 3/4, Japan 18) (7/8 in.). Found whilst searching with a metal detector on 28th March 2022 Mr Graham Higgins, near Hatford, Oxfordshire, UK.Accompanied by a copy of the report for HM Coroner by the Finds Liason Officer (FLO) for the British Museum's Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) for Oxfordshire under Treasure reference number OXON-FC03F7. Accompanied by a copy of the letter from HM Senior Coroner for Oxfordshire disclaiming the Crown's interest in the find. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

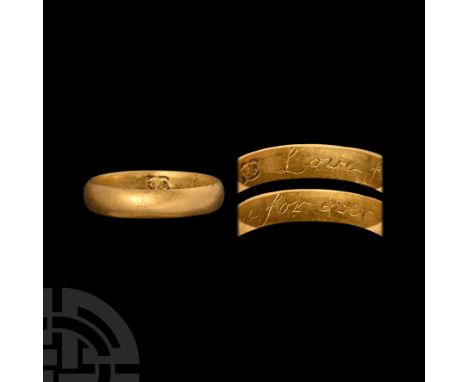

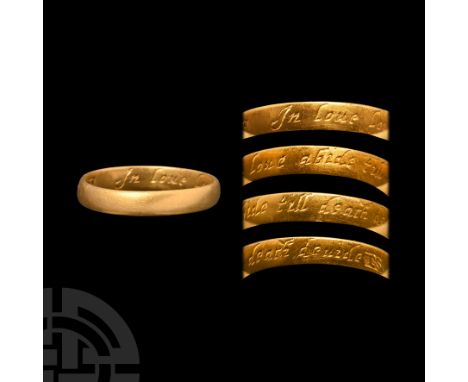

18th century A.D. Inscribed to the hoop interior together with maker's stamp 'RD' within shaped cartouche. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, 1931, p.72, for this posy.6.16 grams, 22.60 mm overall, 19.48 mm internal diameter (approximate size British T, USA 9 1/2, Europe 21.26, Japan 20) (3/4 in.). From the collection of a North American gentleman, formed in the 1990s. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

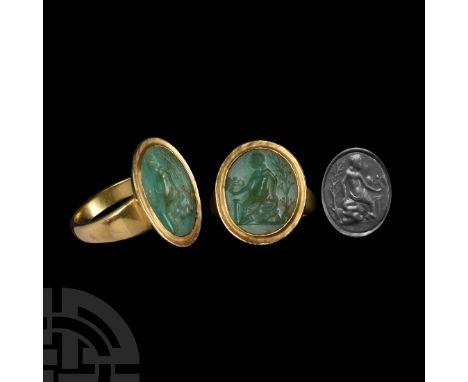

Roman, 1st -2nd century A.D. or later. The chrysoprase gemstone with intaglio Venus seated beside a tree, altar and miniature Victory before her; mounted in a later gold ring; accompanied by a museum-quality impression. Cf. gemstone in the Royal Collection, later remounted as a pendant, under accession number RCIN 65741.12.04 grams, 24.22 mm overall, 20.19 mm internal diameter (approximate size British T, USA 9 1/2, Europe 21.26, Japan 20) (1 in.). Ex property of a London gentleman; acquired London art market, 1970-1980. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

Circa 1st century A.D. Each a scrolled bar formed as a serpent or other animal with stylised geometric detailing; attachment perforations to both terminals. Cf. Bishop, M.C. & Coulston, J.C.N., Roman military equipment, from the Punic wars to the fall of Rome, London, 2006, p.96, fig.51,3 for similar.19.6 grams total, 64-66 mm (2 1/2 in.). Acquired on the London art market, 1980s-1990s. In the 1st century B.C.-1st century A.D., the Celtic fastening system of the ring mail armour (gallica, lorica ferro aspera) became the standard in the Imperial Roman army, with a pivot attached to the breast and hinged to the edges of the humeralia (shoulder guards). The chest fastener had various different designs. The double hooks, S-shaped and usually with snake-head terminals, were secured by a central rivet on the chest. The system allowed excellent freedom of movement, giving greater protection to the shoulders and the arms. Similar fasteners for infantry mail have been found on the Kalkriese battlefield, some of them also decorated with niello and inscribed with the name of the soldier. [2]

10th-11th century A.D. The scabbard with bronze hoop reinforcements to the upper third decorated with bands of punched holes; lateral suspension flap between bronze plates with reserved interlace motifs on hatched field; hilt with Borre Style ring-chain motifs to the upper end; hollow to the upper face. Cf. Arbman, H., Birka I: Die Gräber, Uppsala, 1940, pl.6.119 grams, 24 cm (9 1/2 in.). From the collection of a North American gentleman, formed in the 1990s.[No Reserve]For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

19th century A.D. With 11cm (4 1/2) side-by-side double barrel hinged for loading/extraction, fitted with hinged bayonet to top, folding triggers, with wood butt and steel but cap with lanyard ring; action working. 505 grams, 22.5 cm (8 7/8 in.). Acquired on the UK market. Property of a Kent collector. Sold as an exempt item under Section 58 (2) of the Firearms Act, 1968, to be held as a curiosity or ornament. No license required but buyer must be over 18 years of age. Overseas bidders should note that, due to UK regulations governing export of all firearms, overseas buyers will need to make arrangements for shipping this lot out of the UK directly, by air freight, with a specialist company or agent.

Circa 1900 A.D. Each with a long and narrow blade, the longer of square section, the shorter rectangular, each fitted with traditional slender, straight hilt, guard and finger-ring. 657 grams total, 85-106 cm (33 1/2 - 41 3/4 in.). Acquired from Czerny's Auctions, Italy, 2016, lot 280. The Kusmirek Collection, UK.Accompanied by a copy of Czerny's invoice and listing.[2, No Reserve]

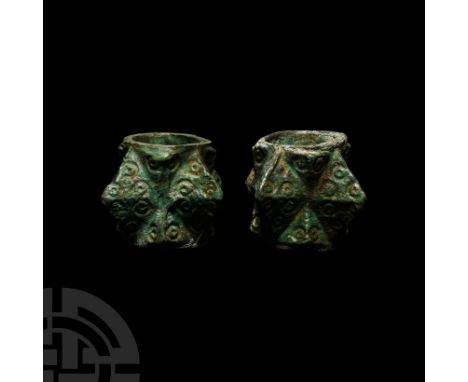

14th century A.D. Each with four large triangular-shaped projections flanked by smaller projections; decorated with groups of ring-and-dot ornaments. Cf.Gilliot, C., Weapons and Armours, Bayeux, 2008, pp.160-161, for similar maceheads.155 grams total, 46 mm each (1 3/4 in.). Private collection, UK, formed in the 1980s. The Kusmirek Collection, UK. The polygonal mace evolved into the hexagonal winged mace. Originating in the East, this weapon spread across Eastern Europe during the 13th century A.D., and from there to the West. The winged mace, used by the western Europeans, was almost certainly based upon Eastern Roman or Islamic prototypes. It is relevant to note that the polygonal mace was widely used by the eastern cavalrymen (like Turkish and Mongols), during the 14th century A.D. [2]

10th-12th century A.D. Comprising three mounts with bounding lion motifs, five heart-shaped mounts also showing leaping lions and a plain semi-circular mount; all with mounting lugs to reverse. Cf. Baranov, V.S., Izmaylov, I.L., 'On attribution of a signet ring from Bolgar excavations of 2010' in Archaeology of the Eurasian steppes, no.6, 2019, pp.269-276, for iconography.67 grams total, 27-52 mm (1 - 2 in.). From the collection of a North American gentleman, formed in the 1990s. [9, No Reserve]For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

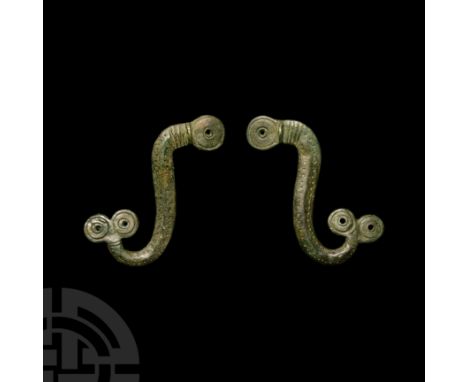

1st century A.D. Each a scrolled bar with gently carinated upper face, formed as serpents or other animals with stylised geometric detailing; attachment perforations to one terminal. Cf. Bishop, M.C. & Coulston, J.C.N., Roman military equipment, from the Punic wars to the fall of Rome, London, 2006, p.96, fig.51,4 for similar.16.5 grams total, 65 mm each (2 1/2 in.). Acquired on the London art market, 1980s-1990s. In the 1st century B.C.-1st century A.D., the Celtic fastening system of the ring mail armour (gallica, lorica ferro aspera) became the standard in the Imperial Roman army, with a pivot attached to the breast and hinged to the edges of the humeralia (shoulder guards). The chest fastener had various different designs. The double hooks, S-shaped and usually with snake-head terminals, were secured by a central rivet on the chest. The system allowed excellent freedom of movement, giving greater protection to the shoulders and the arms. Similar fasteners for infantry mail have been found on the Kalkriese battlefield, some of them also decorated with niello and inscribed with the name of the soldier. [2]

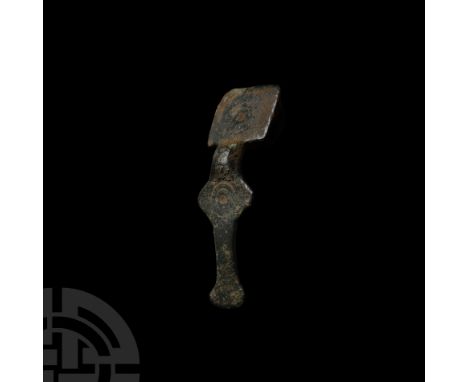

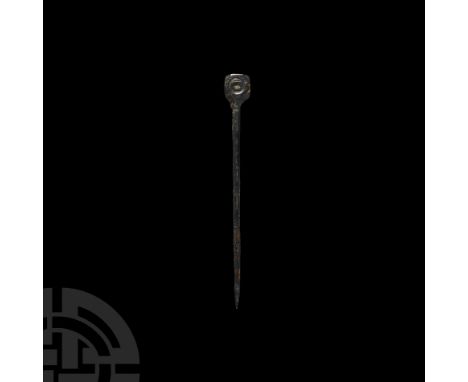

9th-11th century A.D. Decorated with punched ring-and-dot motifs to the head and bow; remains of pin lug to reverse. 5.8 grams, 41 mm (1 5/8 in.). From the collection of a North American gentleman, formed in the 1990s.[No Reserve]For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

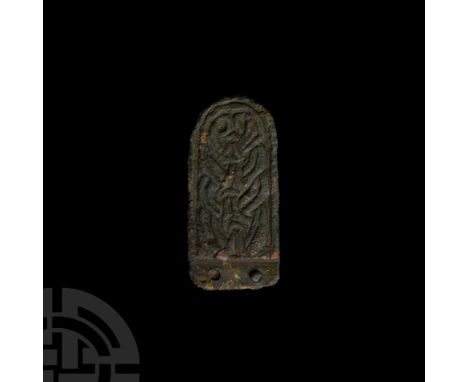

10th-11th century A.D. Comprising a tongue-shaped body, panel of reserved tendril interlace to one face, ring-and-dot motifs to the reverse; two rivets to the upper edge. 12.6 grams, 43 mm (1 3/4 in.). Found near Thetford, Norfolk, UK.[No Reserve]For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

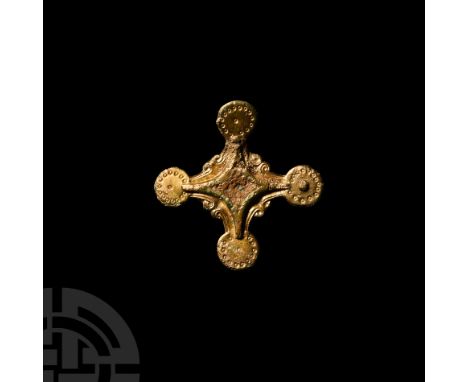

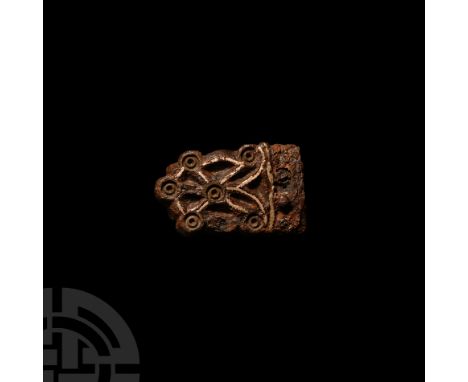

6th-7th century A.D. Or casket mount, each arm terminating in a discoid plaque with a ring of punched pellets, the arms with scroll detailing to the junctions; central raised plaque with lozengiform cell filled with the remains of organic material; five lugs to the underside; some restoration. 18.99 grams, 42 mm (1 5/8 in.). Found UK. Acquired 1978-2008. Ex property of a West Yorkshire lady.[No Reserve]For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

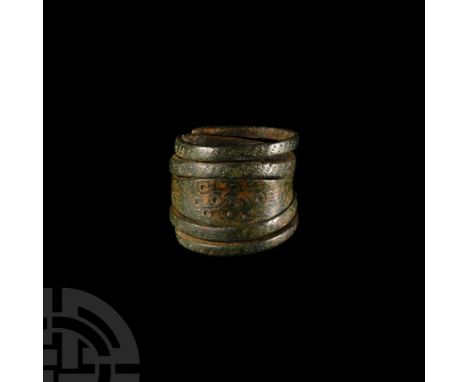

9th-11th century A.D. The body hexagonal in cross-section, facetted terminals and free-running tongue, punched ring-and-dot motifs and dense panels of annulets in three zones around the body. Cf. The British Museum, museum number 1921,1101.200, for similar.70 grams, 82 mm (3 1/4 in.). From the collection of a North American gentleman, formed in the 1990s.[No Reserve]For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

6th-7th century A.D. Or a hanging-bowl chain comprising: nine sets of two parallel-twisted 8-shaped links, with interstitial H-shaped twisted elements, the lower four each with a standing bull figure with prominent horns; a lateral hook with herringbone twisted shank; lower hooked flange with four herringbone-twist bars with looped ends; suspension ring and four-bar herringbone-twisted shank. 3.1 kg, 1.03 m (40 1/2 in.). Acquired 1971-1972. From the collection of the vendor's father. Property of a London, UK, collector. The chain and fittings closely resemble those recovered from Mound 1 at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, England (British Museum accession ref. 1939,1010.167). It is understood that the chain was used to support a cauldron above the hearth, with additional hooks and suspension brackets for ancillary vessels. The bull-head detailing was present on the wrought-iron stand (ref. 1939,1010.161) from the same grave. [No Reserve]

10th-12th century A.D. With stamped triangle and pellets to each face, curled suspension loop and silver-wire ring. Cf. West, S., A Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Finds From Suffolk, East Anglian Archaeology 84, Ipswich, 1998, item 126(5), for type.2.74 grams, 39 mm (1 1/2 in.). Acquired on the EU art market around 2000. From the collection of a North American gentleman.

9th-12th century A.D. Comprising one polished face, raised rim, central ring, dense band of zoomorphs enmeshed in tendrils. 52 grams, 80 mm wide (3 1/8 in.). Acquired in the 1990s. Ex property of a German collector.[No Reserve]For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

9th-11th century A.D. Comprising a roughly semi-circular profile, suspension lug to apex, slightly flared arms with zoomorph decoration, punched ring-and-dot and zigzags to both sides. 26.8 grams, 65 mm (2 1/2 in.). From the collection of a North American gentleman, formed in the 1990s.[No Reserve]For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

9th-11th century A.D. Punched ring-and-dot decoration to the expanded central section, orderly striations of pecking over the rest of the body. 11.13 grams, 23.03 mm overall, 18.64 mm internal diameter (approximate size British Q, USA 8, Europe 17.49, Japan 16) (1 in.). From the collection of a North American gentleman, formed in the 1990s.[No Reserve]For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

10th-11th century A.D. Composed of two crescentic arms, bifacial pecked and punched ring-and-dot motifs to the body; two perforations for attachment. 24 grams, 46 mm (1 3/4 in.). From the collection of a North American gentleman, formed in the 1990s.[No Reserve]For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

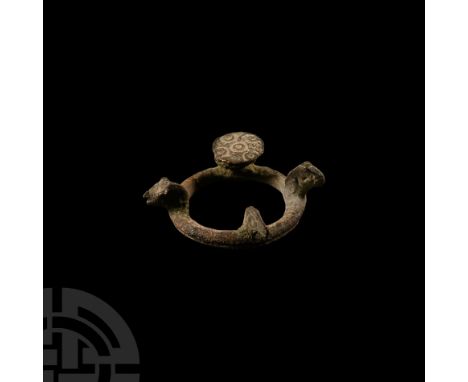

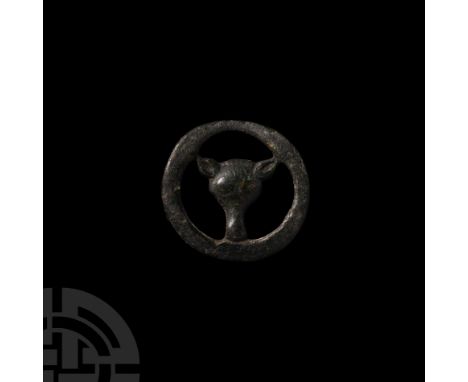

9th-12th century A.D. Comprising an outer ring with wolf mask in low relief at the centre. Cf. MacGregor, A. et al., A Summary Catalogue of the Continental Archaeological Collections, Oxford, 1997, item 24.1.3.4 grams, 26 mm (1 in.). Ex property of an American collector; acquired 1980-2000.[No Reserve]For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

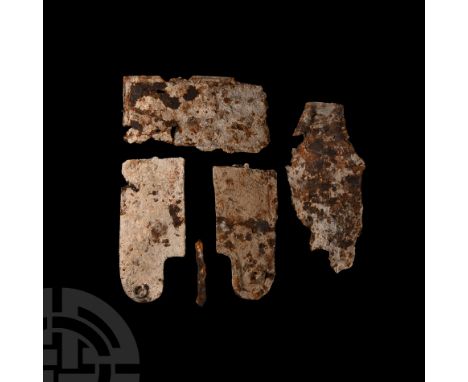

6th-7th century A.D. Comprising thirty-eight 8-shaped iron links, with interstitial H-shaped twisted elements; securing ring at the upper end; iron ring at the lower end with thick linked ring and two substantial shackles, each a pair of parallel bars with a loop at each end; attached to each a flat rectangular-section fetter with substantial retaining rivet. Cf. iron collar from John’s Lane, Dublin, now in the National Museum of Ireland.4.45 kg, 2.57 m long (101 in.). Acquired 1971-1972. From the collection of the vendor's father. Property of a London, UK, collector. The shackles are formed with an elliptical void in order to accommodate a human foot, closed with an iron rivet which could not have been easily removed without heating the metal. [No Reserve]

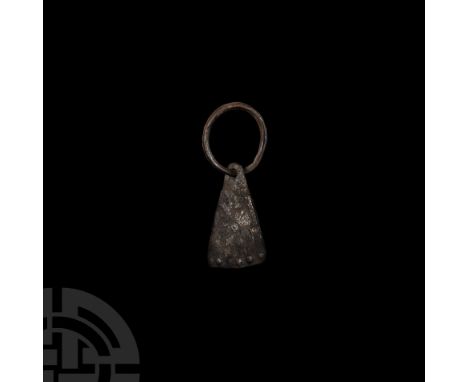

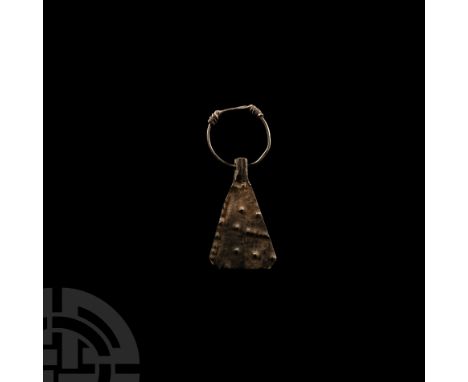

9th-12th century A.D. or earlier. The free-running, wedge-shaped pendant displaying repoussé pellets; slender ring with overlapping terminals, each forming a coiled sleeve around the opposite arm. 2.49 grams, 53 mm (2 in.). Acquired on the EU art market around 2000. From the collection of a North American gentleman.

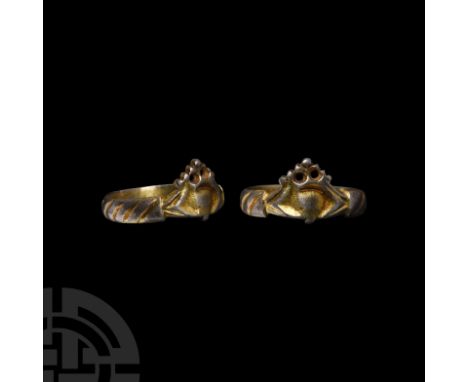

Circa 1400-1550 A.D. With twisted-band detailing to the hoop, bezel formed as two hands supporting a heart and a crown with openwork detailing; marked to the inner face with PAS reference number '11089'. Cf. Chadour, A.B., Rings. The Alice and Louis Koch Collection, volume I, Leeds, 1994, item 728, for type.3.70 grams, 22.70 mm overall, 19.57 mm internal diameter (approximate size British T, USA 9 1/2, Europe 21.26, Japan 20) (7/8 in.). Found while searching with a metal detector near Romney, Folkestone and Hythe, Kent, UK, on Wednesday 1st August 2018.Accompanied by a copy of the British Museum's Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) report no.KENT-11089B. Accompanied by a copy of letters from the Coroner confirming that the Crown's interest in the ring under treasure reference no.2018T662 has been disclaimed. Accompanied by copies of receipts from the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport.

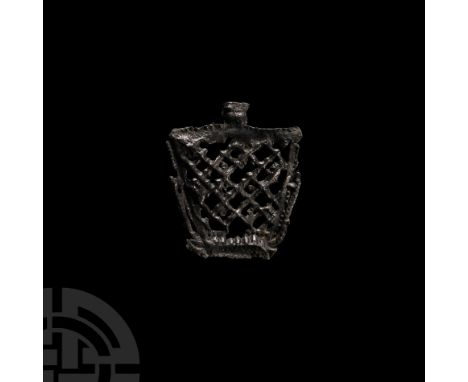

15th century A.D. Comprising a trapezoidal frame with latticework and tab to the long edge; from a purse pendant. Cf. Spencer, B., Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges, Woodbridge, 2010, item 176b.4.35 grams, 39 mm (1 1/2 in.). Found Thames foreshore spoil, 1980s. The purse was originally suspended on straps from a badge bearing a fleur-de-lys within a ring. [No Reserve]

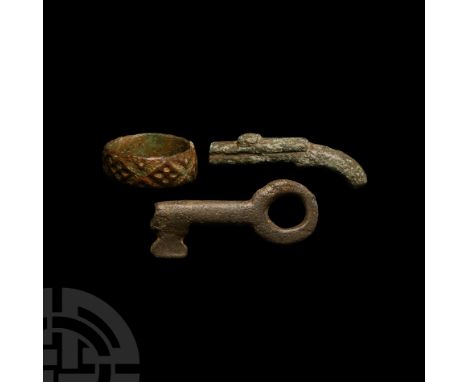

13th-14th century A.D. Retaining an articulate flat-section tongue looped around a narrow inset in the ring; the outer face decorated with radiating triangles over punched pellets. 2.01 grams, 21 mm (3/4 in.). Buckinghamshire, UK, private collection; formed in the 1980s.[No Reserve]For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

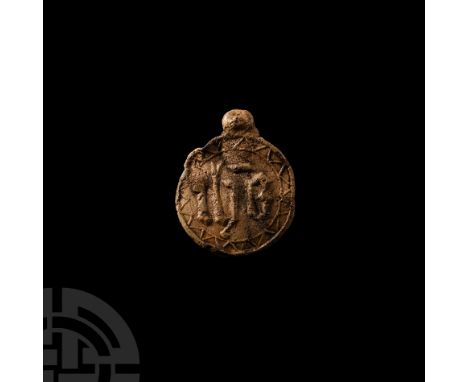

14th-15th century A.D. Discoid plaque with image of crowned St Margaret to obverse, 'ihs' monogram to reverse in a segmented ring border. 8.02 grams, 33 mm (1 1/4 in.). Found near Ketsby, Lincolnshire, UK. Attributed to the shrine at Ketsby, Lincolnshire, England and found nearby. [No Reserve]

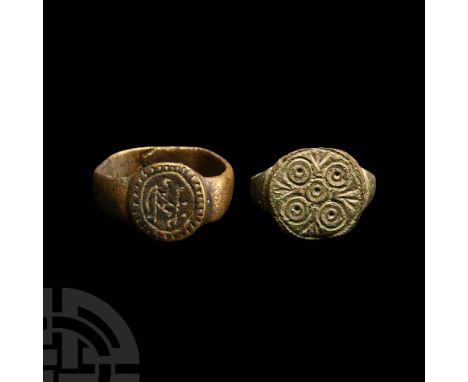

15th-16th century A.D. Comprising one example with ring-and-dot motifs in a cruciform arrangement; one with possible monogram within a pecked border. 10.3 grams total, 20-23 mm (3/4 - 7/8 in.). From the collection of a North American gentleman, formed in the 1990s.[2, No Reserve]For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

Circa 1800 A.D. Comprising a slender hoop with shell-shaped shoulders, hinged oval bezel with secret compartment revealing a silvered skull framed by turquoise cabochons, the eyes set with diamonds or other stones; accompanied by a ring box. Cf. Oman, C.C., British Rings 800-1914, London, 1974, plate 90(D), for ring with compartment in which to place a lock of hair, etc.3.95 grams, 20.00 mm overall, 16.20 mm internal diameter (approximate size British J, USA 4 3/4, Europe 8.69, Japan 8) (3/4 in.). Acquired from Berganza, Hatton Garden, London, 2016. Property of an East Sussex collector.Accompanied by a copy of the Berganza invoice. This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate no.11666-197585. Likely a ring of the memento mori genre.

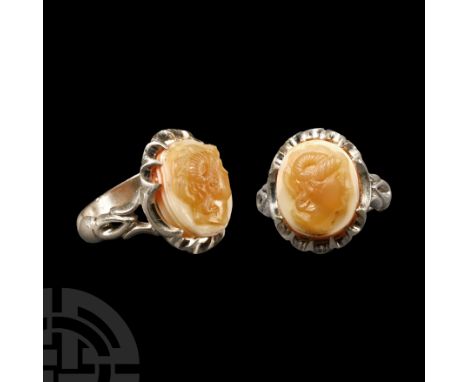

Circa 19th century A.D. The onyx cloison displaying a carved male bust in profile right, set into a later gold ring with scooped shoulders. 5.48 grams, 26.02 mm overall, 18.54 mm internal diameter (approximate size British Q, USA 8, Europe 17.49, Japan 16) (1 in.). Ex property of a London gentleman; acquired before 1970.

Late 19th-early 20th century A.D. With profile bust reserved in high-relief, set into the bezel of a silver finger ring. 11.22 grams, 32.35 mm overall, 20.09 mm internal diameter (approximate size British T 1/2, USA 9 3/4, Europe 21.89, Japan 21) (1 1/4 in.). Acquired by the vendor's father on the UK art market, before 1990.

Circa 17th century A.D. Of curved form and with remaining rivets for attachment of the tang-scales; single-edged blade with sunburst and ring-and-dot motifs to the lower edge on one face, joined by plain bands. See Capwell, Dr. T., Knives, Daggers and Bayonets, London, 2009, p.32, for type.165 grams, 35 cm (13 3/4 in.). Acquired 1990s-early 2000s. East Anglian private collection.[No Reserve]

Dated 12 October 1847 A.D. With everted upper and lower rim engraved with foliate motifs to the front faces, recessed central band engraved with a floral panel and inscription 'IN MEMORY OF', with continued inscription to the interior in cursive script 'O. Coates Obt. 12. Oct 1847, aet 54', followed by the hallmarks comprising: HI or IH maker's mark, anchor for Birmingham, 18 carat mark, duty mark and date letter 'Gothic A' for 1824; field to exterior keyed to receive enamel; seemingly an older ring with later inscription. 1.50 grams, 19.63 mm overall, 17.78 mm internal diameter (approximate size British O, USA 7, Europe 14.98, Japan 14) (3/4 in.). Found Romney Marsh area, Kent, UK. Property of a Kent gentleman.

19th century A.D. Comprising: one with an openwork D-shaped plaque, tendril and leaf detail with inset cloisons of ruby, sapphire, tourmaline and glass, penannular hoop with disc terminals, stamped '???' and other marks to the ring and shank; one with openwork triangular plaque with scrolled tendrils and central ropework star, pierced lobe finial, penannular hoop with lobe terminals, stamped lozenge to the lobe finial and others to the hoop. 20.8 grams total, 57-80 mm (2 1/4 - 3 1/8 in.). Acquired 1970s. Ex property of an Essex, UK, collector. The stones set in the D-shaped plaque are a mixture of gem cuts from several time periods, the earliest being Tudor. It is likely that they are the silversmith's accumulation from several pieces of older jewellery broken down for their metal and stones. [No Reserve]

17th-18th century A.D. Displaying a circumferential band of six-armed stars to the exterior with some remains of enamelling to the fields; the interior inscribed 'THY + FAITH + FAVLS + NOT' (possibly: thy faith fails/false not). Cf. The British Museum's Portable Antiquities Scheme, record id. SWYOR-FA9028, for a ring with the same exterior design, dated 16th-17th century A.D. and record id. WMID-C2D522, for an example of the use of 'favls' to mean 'false'.1.20 grams, 16.93 mm overall, 14.95 mm internal diameter (approximate size British I, USA 4 1/4, Europe 7.44, Japan 7) (5/8 in.). Acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

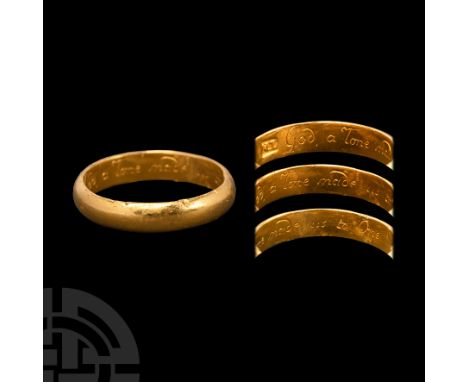

18th century A.D. Inscribed 'God a lone made us to One WME' around the interior, the initials being M for family name with W for male forename and E for female forename, with maker's mark stamped 'NL' in rectangular cartouche, possibly for the northern goldsmith Nicholas Lee. 5.59 grams, 22.23 mm overall, 19.15 mm internal diameter (approximate size British R, USA 8 1/2, Europe 18 3/4, Japan 18) (7/8 in.). From the collection of a North American gentleman, formed in the 1990s. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

17th-18th century A.D. Composed of a slender hoop inscribed around the interior, maker's stamp 'TS' in rectangular cartouche, possibly for goldsmith Thomas Sharp. Cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1534, for this maker's stamp or very similar and AF.1311, for a similar posy; cf. The British Museum's Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, record id. KENT-F5292E, for a very similar posy.3.03 grams, 19.90 mm overall, 17.05 mm internal diameter (approximate size British O, USA 7, Europe 14.98, Japan 14) (3/4 in.). From the collection of a North American gentleman, formed in the 1990s. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

16th-17th century A.D. Composed of a decoratively notched hoop divided into chased rhomboidal panels displaying foliate tendrils and horizontal hatching alternately; the interior inscribed in Roman capitals with the Latin phrase: 'x x x x VIVE x VT x VIVAS'. Cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, record ids. KENT-1F5049 and DUR-23C436, for other rings with this inscription; cf. The V&A Museum, accession number M.75-1960, for a similar design exterior dated 16th century A.D.2.08 grams, 19.25 mm overall, 17.40 mm internal diameter (approximate size British M 1/2, USA 6 1/4, Europe 13.09, Japan 12) (3/4 in.). Acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK. The literal translation here is live that you may live, but is meant to convey the sentiment: live life to the fullest. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

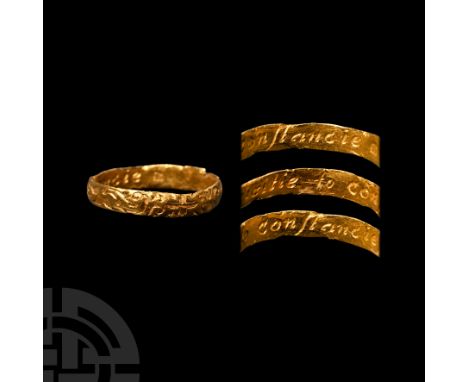

Late 17th-18th century A.D. Composed of a slender convex hoop engraved with crowned conjoined hearts flanked by birds, in turn pursued by bounding hounds, scrolling foliage and a cross at base; trace remains of enamelling; interior inscribed in cursive script: 'No felicitie to constancie', together with maker's stamp 'IY' in a square cartouche. Cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme, record ids. HESH-23BC20 and SUR-6A3232, for broadly comparable design elements.1.38 grams, 17.35 mm overall, 15.48 mm internal diameter (approximate size British J, USA 4 3/4, Europe 8.69, Japan 8) (3/4 in.). Acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK. IY goldsmith's mark possibly for James Young of London, see Jackson, Sir C.J., English Goldsmiths and Their Marks, London, 1921, p.215. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

-

1087795 item(s)/page