We found 307192 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 307192 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

307192 item(s)/page

A BRONZE FIGURE OF A HAMSA, DECCAN, SOUTHERN INDIA, CIRCA 18TH CENTURY probably the base of a lamp, the bird of stylised form, with elongated beak, crested head and wearing a trio of necklaces, standing on square flared base, 25cm highProvenance: Formerly in the collection of the late Peter Cochrane, acquired in 1977, inv. no. 77/29. Sold in these rooms, 10 April 2014, lot 75

A BRONZE HANGING LAMP, JAVA, INDONESIA, CIRCA 14TH CENTURY the circular flared base surmounted by circular reservoir with four projecting wick holders, a chain attached to the central column with hook at the top, 50cm high (including extended chain)Provenance: Collection of a deceased diplomat, thence by descent.

A Chinese Famille Rose vase, late 19th century, enamelled to the exterior with birds perched on flowering branches, adapted as lamp, the vase 45cm high Provenance: From the estate of Lionel Alfred Martin, Ingram Avenue, London (1855-1933), Chairman of Tate & Lyle. 晚清 粉彩花鳥圖瓶拍品來源:Tate & Lyle集團主席Lionel Alfred Martin 倫敦私人大宅(1855-1933)舊藏 Condition Report: adapted as lamp Condition Report Disclaimer

A mixed lot of ceramics and glassware to include a collection of Atkinson-Jones lustre ware studio ceramics including a table lamp and a footed bowl with metallic gold coloured oxide veining, collection of carnival glass to include three fruit bowls, along with a book on collecting carnival glass, two pairs of ruby flashed and cut hock glasses, and other table glass Location:

A Second War ‘D-Day’ D.S.C. group of five awarded to Acting Commander L. R. Curtis, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, who commanded Assault Group J4 during Operation Neptune Distinguished Service Cross, G.VI.R., the reverse officially dated ‘1944’ and privately engraved, ‘Commander L. R. Curtis, R.N.V.R., Ouistreham, June 6th’; 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star, 1 clasp, France and Germany; Defence and War Medals, with M.I.D. oak leaf, mounted as worn, lacquered, good very fine (5) £1,000-£1,400 --- Provenance: Dix Noonan Webb, December 2006. D.S.C. London Gazette 28 November 1944. M.I.D. London Gazette 8 June 1944. Leonard Rupert Curtis was appointed a Temporary Sub Lieutenant in the “Wavy Navy” in January 1942. Advanced to Lieutenant in April 1942, he joined the landing craft training base Copra in September 1943, which appointment culminated in his appointment to the command of Assault Group J4 on D-Day, a unit comprising the 200th and 201st L.C.I. (S.) Flotillas which landed at “Queen Red” and “Queen White” beaches near Ouistreham. Curtis appears in the acknowledgements of numerous D-Day histories, but no-one was closer to him at the initial landing stage than Lord Lovat, who ‘borrowed’ his bunk during the Channel crossing: ‘The paling stars spelt out ‘Invasion’. It was blowing half a gale and getting light enough to see Curtis, now with his steel helmet on. He had reddish hair and a serious face. A quiet-spoken, dependable man, keenly aware of the importance of the occasion. Rupert was to be awarded the D.S.C. for the work he did that day. I imagine he felt lonely on the crossing: twenty-two boats pitching in line ahead; seven hours of eye-strain darkness, keeping station in rough weather up the swept passage through the minefields. “Twenty miles from the coast and twelve to lowering point,” he shouted against the wind. I nodded respectfully, trying a shivering smile with eyes on the duffle coat. The navigator had done his job well - on course and ahead of the clock. Nautical twilight was past and the sea changing colour to oystershell in the grey dawn when the Aldis lamp blinked on our port bow: “Good morning, Commandos, and the best of British luck.” Curtis and his yeoman spelt out the signal. We made a suitable reply: “Thanks. Think we are going to bloody well need it.” Rupert ran up the battle ensign. War was becoming personal again ... Half-seen through palls of smoke, boats were burning to our left front ... Curtis made a slight alteration of course to starboard. A tank landing-craft with damaged steering came limping back through the flotilla. The helmsman had a bandage round his head and there were dead men on board, but he gave us the V sign and shouted something as the unwieldly craft went by. Spouts of water splashed a pattern of falling shells. Among the off-shore obstacles - heavy poles and hedgehog pyramids with Teller mines attached - we started to take direct hits. Curtis picked his spot to land, increased speed and headed for the widest gap, the arrowhead formation closing on either side. The quiet orders - a tonic from the ridge - raised everybody’s game: “Amidships. Steady as she goes.” The German batteries mistakenly used armour-piercing ammunition in preference to high explosive and bursting shrapnel. Derek’s landing brows were shot away and beyond him Ryan Price’s boat went up with a roar. Max had an unpleasant experience when a shell went through his four petrol tanks without exploding. Rear headquarters got away with minor casualties. Our command ship took two shells in the stern. It happened in the last hundred yards. There was no time to look back. The impact must have swung us round for two boats, Max’s and mine, touched down side by side. Each carried four thousand gallons of high-octane fuel in non-sealing tanks aft of the bridge. Had Max blown-up we would have gone with him. Five launches out of twenty-two were knocked out, but the water was not deep and Commandos got ashore wading; a few men went wading in the shell craters’ (Lovat’s March Past refers). Curtis attained the rank of Acting Commander in April 1945 and was released from the Active List in April 1946.

A most interesting Indian Mutiny medal awarded to William Green, Medical Staff Corps, who nursed Florence Nightingale at Scutari when taken with fever, and latterly was with the Shannon's Naval Brigade at Lucknow where he states he was wounded by a ‘slug’ in the arm Indian Mutiny 1857-59, 1 clasp, Lucknow (1st Class Ordy. Wm. Green, Med. Staff Corps) fitted with contemporary T. B. Bailey Coventry silver ribbon brooch, suspension claw re-affixed, polished overall, otherwise nearly very fine £1,200-£1,600 --- William Green was born at St. Luke, Islington, London, circa 1838, the son of James Green. He attested into the Medical Staff Corps in September 1855 with the service number 316. The Medical Staff Corps was improvised in haste to alleviate the dire medical facilities that existed during the Crimea campaign. In August 1856, Judge Advocate General Charles Pelham Villiers declared the Corps illegal and inadmissible, as the word ‘Corps’ was not in the statutes raised by Parliament, and that all M.S.C. ranks were not recognised. The medical services were revised under a new Royal Warrant and named the Army Hospital Corps, although the M.S.C. continued in various guises until 1860. The Muster Rolls for the Medical Staff Corps [WO 12/19010-19015] confirm that Green sailed on the steam vessel Thames with the second draft of the M.S.C. which left Chatham on 24 October and arrived at Scutari on 12 November 1855. It consisted of 1 steward, 4 assistant stewards, 8 assistant ward-masters and 147 orderlies. On arrival at Scutari, Green served under Florence Nightingale before going to the Balaklava hospital on 27 November where he transported the sick and wounded. He was placed in charge of the Recruit hospital on the front line as a First Class Assistant, before returning to Scutari where he nursed Florence Nightingale when she taken ill with fever, then remaining there for the duration of the war. Green was not entitled to the Crimean medals, arriving too late for qualification. Intriguingly, the Florence Nightingale Museum holds a letter from Florence Nightingale to William Green dated 4 December 1899, although it is neither written nor signed in Florence Nightingale's hand. The Collection's Manager states that in later life Florence Nightingale was bedridden, being afflicted by blindness and depression and relied on several assistants to whom she dictated a response to the many letters she received. The museum confirms the letter to be genuine and is one of those hastily dictated replies, later rewritten by her assistants in a more legible hand, with the original dictated letter filed in their collection. It reads: ‘My poor brave friend, We feel so sorry for you and we grieve with you. But it is giving glory to God, as I know you feel, to suffer as you do for him. He is bearing your burden for you... and blessing you,’ and continues that she plans to send him a book or two which she thinks he will like, ending with ‘Your sincere friend, Full of respect – F. Nightingale’. Green returned to England and served short periods in Ireland and Aldershot before being sent out to India during the first quarter of 1858. He was firstly sent up country with that ‘memorable party of sailors who volunteered for land service under Captain Peel of the Shannon who dragged their guns many a hundred miles by forced marches both day and night.’ His work of mercy then took him to Delhi, and his later experiences with the gallant sailors brought him hard work and dreadful sights at Lucknow. Green also had to do his time in the trenches and once, while dressing wounds in the field before Lucknow, received a ‘slug’ in the arm [not found in casualty lists]. On another occasion the rebel cavalry came near to cutting off the medical staff, but he managed to escape. He speaks with considerable passion of the hardness before Lucknow. On one occasion, three men of the M.S.C. had to deal with 90 casualties described as ‘mostly blown up cases’. The work lasted day and night with no sleep and little food, so little wonder that men fell out with sunstroke, fatigue and ‘shear wear-out’. His medal roll shows him attached to the field hospital at Lucknow as a 1st Class Orderly. An accompanying newspaper cutting under the heading, ‘Her father nursed Lady with lamp’ reads: ‘after the Indian Mutiny Mr Green married a Calcutta hospital matron and returned with his wife to England and made his home in Stafford.’ The Indian archives confirm Green married the widow Charlotte Carter, née Pratt (daughter of Benjamin Pratt), on 17 October 1859 at Colaba, Bombay. William Green left India on 22 June 1860, at which time he was discharged from the service. He became a fish dealer in Stafford and also acquired or managed a thriving public-house. Charlotte died on 18 January 1884 and the couple left no issue. On 9 March 1886, he re-married to 17 year-old Hannah, née Spilsbury. William Green died after a long and painful illness in January 1904. Sold with a notebook entitled The Domestick Medical Table by an Eminent Physician. William Green, his book, No. 316, Medical Staff Corps, Chatham. It lists diseases and cures for 70 ailments, from ague to chilblains, to be treated by unguents, lotions, powders and poultices using morphia, dandelions, tartarised antimony, caraway seeds, and the frequent use of leeches; together with a fine portrait photograph of William Green in later life wearing his mutiny medal; contemporary copies of his obituaries; a small Holy Bible; and several related press cuttings. William Green's story was collated from his obituary in the Lichfield Mercury of February 1904, and his war reminiscences from the Staffordshire Chronicle's ‘Old Stafford Heroes’ of 1892. The Florence Nightingale Museum confirms that they hold a letter from Miss Nightingale to William Green.

A Great War D.S.C. group of eight awarded to Commander H. Forrester, Royal Navy, for services whilst commanding torpedo boat destroyers in the Dover Patrol Distinguished Service Cross, G.V.R., the reverse hallmarked London 1915, and attractively engraved ‘Lieut,. Henry Forrester, R.N. Presented by King George V. Oct. 4th 1916. “Carried out dangerous patrol duties with marked ability”; 1914-15 Star (Lieut. H. Forrester. R.N.); British War and Victory Medals, with M.I.D. oak leaves (Lt. Commr H. Forrester. R.N.); Defence and War Medals 1939-45; France, Third Republic, Croix de Guerre, reverse dated 1914-1917, with bronze palm on riband; Portugal, Republic, Military Order of Avis, Officer’s breast badge, silver-gilt and enamel, with rosette and riband bar, enamel chips to the last, otherwise good very fine (8) £1,600-£2,000 --- D.S.C. London Gazette 25 July 1916: ‘Carried out dangerous patrol duties with marked ability.’ M.I.D. London Gazette 25 July 1916 and 26 April 1918. French Croix de Guerre London Gazette 17 May 1918: ‘Awarded for mine laying operations.’ Portuguese Order of Avis London Gazette 4 February 1921: ‘Officer escorting Portuguese Expeditionary Force to France.’ Henry Forrester was born at Colinton, Midlothian, on 11 October 1887, and passed out of Britannia on 15 May 1904; Midshipman, 30 July 1904; Lieutenant, 1 April 1910; Lieutenant-Commander, 1 April 1918; Commander (Retired), 11 October 1927. In January 1915 Forrester was given command of the torpedo boat destroyer H.M.S. Kangaroo, part of the Sixth Flotilla in the Dover Patrol. He was appointed to the command of the torpedo boat destroyer H.M.S. Leven on 2 December 1915, and was awarded the D.S.C. for his work with the Dover Patrol in offensive operations on the Belgian Coast during the winter months of 1915-16. In June 1917 he transferred his command to the torpedo boat destroyer H.M.S. Meteor, again with the Dover Patrol, and did good work in mine laying operations as related in Keeping the Seas, by E. R. G. R. Evans [’of the Broke’ fame]: ‘We had a very bright sample of officer attached to our patrol in the person of Lieut.-Commander Henry Forrester, D.S.C., who commanded the mine-laying destroyer Meteor. He was absolutely without fear, and I personally had more to do with with Forrester than with many of the other junior officers commanding ships of the Dover Patrol. In 1917 particularly, I used to escort him to a position near the Thornton Ridge, where he had established a zero mark buoy, from which he worked to lay his lines of forty mines or so. A description of one night will do for all. The barrage patrol would withdraw at dusk; the vessels would anchor in Dunkirk Roads, or to the northward of the bank which protects the roads, according to the state of tide for that night. A couple of hours before high water, the Meteor would take station abeam of the commanding flotilla leader and a little procession would form up to accompany her to the zero point from which she worked to get into position for laying. The flotilla leader, with her following of modern destroyers, would screen the Meteor up to the Thornton Ridge, or to whatever zero point had been decided on, and then, if no enemy vessels were met with, “g” would be flashed from Forrester’s ship, and he would proceed independently over to the prescribed position where his mines would be deposited. Personally, I loved these night mine-laying stunts; I had grown tired of seeing the enemy on the horizon and never being able to close him, on account of our mine barrage, but night time brought such boundless possibilities. A new division of destroyers might come from Wilhelmshaven to join the Flanders flotilla; a destroyer might be met with, intent on bombarding Lowestoft, Aldburgh, or some other fishermen’s home; small “A” class T.B.D,’s might be met with, or even enemy trawlers: a chance of a scrap we always looked forward to, and our personnel was splendid. I frankly admit that German gunnery was pretty advanced but they never profited sufficiently by it, and they were not out to fight. Our fellows certainly were intent on fighting, and if I have any criticism to make in this little volume on our own sailors, it is that they treated the war as a football match, rather than a contest of brains. Whenever I accompanied Forrester and his Meteor I felt a thrill of pride run through me, for this little red-faced man must have crossed and re-crossed the German minefields on almost every occasion when he took his Meteor up the coast. His work was splendid, and I shall never forget the feeling of apprehension which crept over me when I saw the little Meteor disappearing into the darkness. The impression left on my mind was a cloud of black smoke, a phosphorescent wake and a tin kettle full of men who were keen as mustard; then the period of suspense - an hour, possibly two. We knew her speed; we knew the position in which the mines were to be laid and we therefore anticipated to within five minutes the instant of her re-appearance. It all comes back to me so vividly. The bow wave reported by the look-out, the quickly-flashed challenge and acknowledgement, the feeling of relief and the signal, “Speed 20 knots,” flashed by the lamp which only showed in the direction decided on; the dark shape of the Meteor as she took station abeam of the Broke, and we swirled away homeward to our anchorage off Dunkirk. We always hoped to meet the enemy, but that privilege was denied us, and I feel that privilege will for ever be denied us now that Peace terms specify a reduction of German armaments. We can hardly hope ever to meet them again. Little Forrester was awarded the D.S.C. for his services; I think he also got the Croix de Guerre, and I hope he will receive some other recognition; he certainly deserves the best that can be given.’ Commander Forrester was re-employed in 1940 and appointed to H.M.S. Skirmisher, Milford Haven parent ship. He afterwards served in the Plans Division and as Chief Staff Officer (Admin.) to Commodore (D). He was placed on the Retired List in 1946. Sold with copied record of service, London Gazette entries and other research.

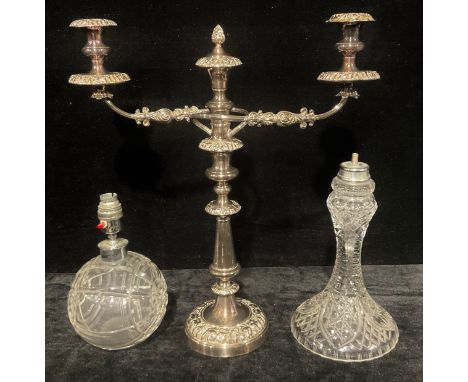

A 19th century brass and moulded glass oil lamp, on stepped circular base, the reeded stem terminating in a stepped capital, the multi-faceted moulded glass font with brass mounts and a pair of burners stamped Patent Duplex, supporting the acid etched globular shade and clear glass chimney, 65cm high including chimney; another, 19th century brass and moulded glass oil lamp, on octagonal base with spreading acanthus leaves terminating in a stylised leaf socle, the multi-faceted moulded glass font with brass mounts and a pair of burners stamped Wright & Butler Birmingham, supporting the acid etched multi-faceted shade with ribbon tied laurel wreath and clear glass chimney, 59.5cm high including chimney; a glass chimney, 24.5cm high (3)

-

307192 item(s)/page