The Great War ‘Serbian Retreat’ D.S.O. group of nine awarded to Commander M. E. Cochrane, Royal Navy Distinguished Service Order, G.V.R., silver-gilt and enamels, with integral top riband bar; China 1900, 1 clasp, Relief of Pekin (Sub. Lieut. M. E. Cochrane, R.N., H.M.S. Centurion); Africa General Service 1902-56, 1 clasp, Somaliland 1902-04 (Lieut. M. E. Cochrane, R.N., H.M.S. Mohawk); 1914-15 Star (Lt. Commr. M. E. Cochrane. R.N.); British War and Victory Medals Commr. M. E. Cochrane. R.N.; Jubilee 1897, silver; Italy, Kingdom, Order of St. Maurice and St. Lazarus, 5th Class breast badge, gold and enamels, enamel damage to centres of cross; Serbia, Order of the White Eagle, 2nd issue, 4th Class breast badge with swords, silver-gilt and enamels, slight enamel damage, mounted for wear, 1914-15 Star sometime gilded, otherwise good very fine and better (9) £2,600-£3,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: R. C. Witte Collection, Dix Noonan Webb, December 2007. D.S.O. London Gazette 14 July 1916. ‘In recognition of their services in connection with the evacuation of the Serbian Army and Italian troops from Durazzo in Dec. 1915, and Jan. and Feb. 1916.’ The recommendation states: ‘Second in Command of the British Adriatic drifters. Was in charge of the drifters covering the evacuation of the Italian troops from Durazzo, the operation taking place in bad weather & under fire from the shore’. Order of St. Maurice and St. Lazarus, Chevalier London Gazette 9 May 1916. Order of the White Eagle, 4th Class London Gazette 1 March 1917. Morris Edward Cochrane was born in 1879, the youngest son of J. H. Cochrane and Charlotte Newton. He entered the Royal Navy as a Naval Cadet on 15 January 1893. He was appointed a Midshipman in February 1895 and was promoted to Sub-Lieutenant in August 1898. During the China War of 1900 he served in the Seymour Expedition to Pekin, and on 9 November 1900 he was promoted to Lieutenant for his services in China. He later served in Somaliland and was mentioned in despatches. He was advanced to Lieutenant-Commander in November 1908 and Commander in May 1919. For his services in the Great War he was awarded the D.S.O., the Italian Order of St. Maurice and St. Lazarus and the Serbian Order of the White Eagle. Sold with copied service papers and other research.

We found 116689 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 116689 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

116689 item(s)/page

Family group: The extremely rare and unusual Iraq 1920 operations D.C.M. group of six awarded to Sergeant C. Downs, Royal Garrison Artillery, attached Inland Water Transport, whose gallant deeds saved the defence vessel Grey Fly after she came under heavy fire on the Euphrates Distinguished Conduct Medal, G.V.R. (1402109 Sjt. C. Downs, R.G.A.); 1914-15 Star (20700 Bmbr. C. Downs. R.G.A.); British War and Victory Medals (20700 Sjt. C. Downs. R.A.); General Service 1918-62, 1 clasp, Iraq (20070 Sjt. C. Downs. R.A.); Army L.S. & G.C., G.V.R., 1st issue (1402109 Sjt. C. Downs. D.C.M. R.G.A.) one or two edge bruises, otherwise very fine and better Pair: Private A. Downs, Manchester Regiment Egypt and Sudan 1882-89, dated reverse, no clasp (2086 Pte. A. Downs, 2/Manch R.); Khedive’s Star, dated 1882, light pitting and bruised over unit, otherwise very fine (8) £2,600-£3,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Just 32 Distinguished Conduct Medals were awarded between the Wars, and only around six of these were for the Iraq operations. D.C.M. London Gazette 28 January 1921: ‘For conspicuous gallantry on 20 August 1920 whilst the defence vessel Grey Fly was proceeding towards Samawah. Being under close fire from the enemy an awning caught fire, and Sergeant Downs drew water from the river, climbed over the roof and put out the fire, and saved the ship.’ As verified by the History of The Royal Regiment of Artillery - Between the Wars 1919-39, by Major-General B. P. Hughes, C.B., C.B.E., another defence vessel - the Fire Fly - employed in these operations was less fortunate, being sent to the bottom of the Euphrates off Kufa by an 18-pounder which had been captured by the Arabs at Hillah - although the breech block had been removed before its capture, the enemy managed to forge a rough substitute. This was just three days before Downs won his D.C.M. in the Grey Fly, while en route to the relief of Samawah, about 70 miles from Kufa.

The outstanding Great War V.C. group of six awarded to Captain H. P. Ritchie, Royal Navy, who won the Senior Service’s first V.C. of the conflict for his gallant command of H.M.S. Goliath’s steam pinnace at Dar-es-Salaam in on 28 November 1914 When the pinnace came under a withering fire, he took over the wheel from his wounded coxswain and steered for the harbour’s entrance, but it took twenty minutes to get clear, in which period he was wounded eight times - on the forehead, in the left hand, twice in the left arm, in his right arm and hip and, finally, by two bullets through his right leg Victoria Cross, the reverse suspension engraved ‘Comdr. Hy. Peel Ritchie, R.N.’, the reverse centre dated ‘28. Nov. 1914.’; 1914-15 Star (Capt. H. P. Ritchie, R.N.); British War and Victory Medals (Commr. H. P. Ritchie. R.N.); Coronation 1937; Coronation 1953, extremely fine (6) £200,000-£260,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- V.C. London Gazette 10 April 1915: ‘Commander Henry Peel Ritchie, Royal Navy, for the conspicuous act of bravery specified below: For most conspicuous bravery on the 28th November 1914 when in command of the searching and demolition operations at Dar-es-Salaam, East Africa. Though severely wounded several times, his fortitude and resolution enabled him to continue to do his duty, inspiring all by his example, until, at his eighth wound, he became unconscious. The interval between his first and last severe wound was between twenty and twenty-five minutes.’ Henry Peel Ritchie was born at Melville Gardens, Edinburgh on 29 January 1876, the son of Dr. Robert Peel Ritchie and Mary (née Anderson). Educated in the city at George Watson’s Boy’s College, he joined Britannia as a Naval Cadet on 15 January 1890 and first served at sea as a Midshipman in H.M.S. Camperdown, between October 1892 and January 1895. Having then been advanced to Lieutenant in June 1898, he qualified as a gunnery officer, in addition to winning the Army and Navy lightweight boxing championship in 1900. He was also commended by Their Lordships of the Admiralty for attempting to save the life of a rating from drowning at Chatham in 1903. First Naval V.C. of the War The outbreak of hostilities in August 1914 found Ritchie serving as Executive Officer of the battleship Goliath in the 4th Squadron in home waters, but she was quickly ordered to East Africa to help locate and destroy the German commerce raider Königsberg. John Winton’s The Victoria Cross at Sea takes up the story: ‘The first naval V.C. of the Great War was won in Dar-es-Salaam, which means ‘Abode of Peace’, the capital of German East Africa. By the end of 1914 the German raiding cruiser Königsberg had been rounded up and trapped in the Rufiji river delta, on the east coast of Africa. Amongst the warships in support of the cruisers who had chased Königsberg was the old pre-Dreadnought battleship Goliath, whose second-in-command, Commander Henry Peel Ritchie, was given the independent command of Duplex, an old German cable ship converted into an armed auxiliary vessel. In November, Ritchie went to Dar-es-Salaam, where a number of German ships had been keeping Königsberg supplied, barricaded as she was some miles inland. While Goliath and the old protected cruiser Fox remained outside, Ritchie made his preparations to enter the harbour. Duplex’s engines were unreliable, so a Maxim gun and extra deck protection were fitted to Goliath’s steam pinnace, which Ritchie himself drove into Dar-es-Salaam on 28th November, accompanied by Lieutenant Paterson, Goliath’s Torpedo Officer, in an ex-German tug called Helmuth, and Lieutenant E. Corson, of Fox, in Fox’s steam cutter. The harbour seemed as peaceful as its name. There were no warships, no signs of hostilities, and two white flags flew as tokens of truce from the harbour signal station flagstaffs. The Governor of Dar-es-Salaam had already agreed that any German ships found in the harbour would be British prizes of war, and could be destroyed or immobilised. While Paterson boarded the Feldmarschall to lay demolition charges and Surgeon Lieutenant Holtom, of Goliath, inspected the bona fides of a hospital ship called Tabora, Ritchie himself boarded the König. She was almost deserted. The few people on board were told to get into her boats, and the ship was demobilised by charges exploded under the low-pressure cylinders of her engines. The next ship, Kaisar Wilhelm II, was also deserted. According to Petty Officer T. J. Clark, the pinnace coxswain, Ritchie’s suspicions were aroused by a clip of three Mauser bullets with their pointed ends sawn off, lying on the deck and showing that someone had been preparing small arms for action. Ritchie had never been at ease in the eerie quietness and emptiness of that harbour, and as a precaution had two steel lighters lashed one on either side of the pinnace. It was as well he did, for they soon heard small arms fire from the main harbour. In spite of the white flags, the Germans were firing on Fox’s steam cutter. At once, Ritchie headed Goliath’s pinnace out into the harbour, making for the entrance. A storm of fire burst upon them, the Germans firing shells and bullets from huts by the water’s edge, from houses in the city, from wooded groves and hills above, even from a cemetery. Without the steel lighters, the pinnace must have been lost. As it was, Clark was hit and Ritchie took over the wheel but he, too, was hit eight times in twenty minutes - on the forehead, in the left hand, twice in the left arm, in his right arm and hip; finally, two bullets through his right leg laid him low and he fainted from loss of blood. Clark, roughly bandaged, took over the wheel from Able Seaman George Upton, and brought the pinnace back alongside Goliath with her decks literally running blood. In retaliation, Goliath opened fire with her main 12-inch guns and flattened the Governor’s house … ’ Subsequent career – Red Sea Patrol – diminishing health Ritchie received his V.C. from King George V at a Buckingham Palace investiture held on 24 April 1915 and, in the following month, returned to light duties with an appointment at the Haslar Gunboat Yards. Then in April 1916, he was appointed to the command of the armed boarding steamer Suva, then employed in the Red Sea Patrol. She lent valuable service in supporting military operations ashore in Palestine over the coming months, including those being undertaken by Lawrence of Arabia. Most notably Suva persuaded the Turkish garrison at Qunfandu to surrender after a bombardment on 7 July 1916, and then remained on station to likewise discourage local dissent by use of her searchlights and guns at night. Ritchie backed up that process by coming ashore to meet the Sheik of the Idrissi at the end of the month. All, however, was not well, for at the year’s end he stood down from his command and was invalided home in the new year. Surveyed at the Royal Naval Hospital (R.N.H.) Haslar on 4 March 1917, he was found to be suffering from ‘delusional insanity’ and was placed on the Retired List as ‘physically unfit’ on the same date. Admitted to the R.N.H. at Great Yarmouth, he remained there until August 1918, when his wife, Christiana, requested he be fully discharged into her care; they had married, in March 1902, at St. Cuthbert’s Edinburgh and had two daughters. Ritchie, who was promoted Captain on the Retired List in January 1924, lived at Craig Royst...

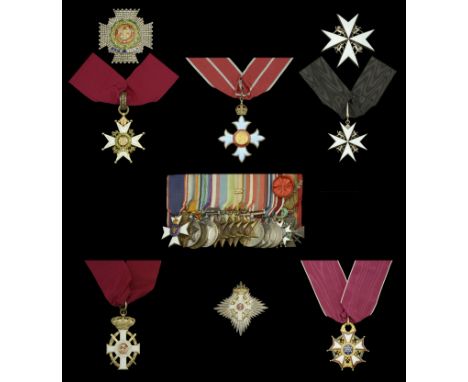

The impressive Second War K.B.E., inter-War C.B., Gallipoli operations D.S.O. group of thirteen awarded to Vice-Admiral Sir George Swabey, Royal Navy Having served ashore with distinction in Gallipoli as a Naval Observation Officer, he rose to senior rank, serving as a Commodore of Convoys 1940-41 and as Flag Officer in Charge at Portland 1942-44: during the latter posting he successfully oversaw the embarkation of an entire U.S. Army Division bound for the Normandy beaches The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, K.B.E. (Military) Knight Commander’s 2nd type set of insignia, comprising neck badge, silver-gilt and enamels and breast star, silver, with silver-gilt and enamel centre, in its Garrard & Co., London case of issue; The Most Honourable Order of The Bath, C.B. (Military) Companion’s neck badge, silver-gilt and enamels, in its Garrard & Co., London case of issue; Distinguished Service Order, G.V.R., silver-gilt and enamels, with integral top riband bar; 1914-15 Star (Commr. G. T. C. P. Swabey, R.N.); British War and Victory Medals, with M.I.D. oak leaves (Capt. G. T. C. P. Swabey. R.N.); 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45; Coronation 1902, silver; France, 3rd Republic, Legion of Hounour, Chevalier’s breast badge, silver, silver-gilt and enamels; United States of America, Legion of Merit, Commander’s neck badge, gilt and enamels, the suspension loop numbered ‘263’, in its case of issue, mounted court-style as worn where applicable, one or two slightly bent arm points on the French piece, otherwise generally good very fine (14) £3,600-£4,400 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- K.B.E. London Gazette 13 June 1946. C.B. London Gazette 3 June 1930. D.S.O. London Gazette 14 March 1916: ‘He rendered very valuable assistance to the Army as Naval Observation Officer. Strongly recommended by General Sir Francis Davies and General Sir William Birdwood.’ Legion of Honour London Gazette 23 March 1917. U.S.A. Legion of Merit London Gazette 28 May 1946. George Thomas Carlisle Parker Swabey was born in Bedfordshire on 22 January 1881 and entered the Royal Navy as a Cadet in Britannia in January 1895. Appointed a Midshipman in January 1897, he subsequently gained seagoing experience in H.M. Ships Cambrian and Venus in the Mediterranean and in the Crescent on the America and West Indies Stations. In 1903 he joined the gunnery establishment Excellent and was afterwards Gunnery Lieutenant in the Revenge and the Irresistible, and First and Gunnery Lieutenant of the Zealandia, in which latter ship he was advanced to Commander in 1913. Soon after the outbreak of hostilities in 1914, Swabey joined the flagship Lord Nelson, and in her sailed for the Dardanelles. He was subsequently appointed a Naval Observation Officer to the Land Forces employed in that theatre of war and was specifically awarded his D.S.O. ‘for services in action during the Gallipoli operations April 1915 to January 1916’, which period also witnessed him being mentioned in despatches by General Sir Charles Munro (London Gazette 12 July 1916). From 1916-17 he served as Executive Officer of the Lord Nelson in the Eastern Mediterranean and in June 1918 he was advanced to Captain. Between the Wars Swabey held several senior appointments, including those of Deputy Director of Naval Ordnance 1921-23; Captain of the Royal Naval College, Greenwich 1924-26 and Commodore Commanding the New Zealand Station 1926-29, when he was the first member of the R.N. to serve on the Royal New Zealand Naval Board. Advanced to Rear-Admiral in the latter year, he was also appointed an A.D.C. to the King and created a C.B. Having been advanced to Vice-Admiral on the Retired List in 1935, Swabey was recalled in September 1939, when he became one of that gallant band of retired Flag Officers to assume the duties of a Commodore of Convoys, in which capacity he served from 1940-41; one newspaper obituary states that ‘after two years’ service on the high seas, Swabey’s ship was sunk from under him and he was exposed for several days in an open boat.’ Then in 1942 he hoisted his Flag as Vice-Admiral in Charge at Portland, where he was entrusted with the preparation for, and execution of, the launching of one of two U.S. Army Divisions to assault the Normandy beaches in June 1944. He was subsequently presented with an official Admiralty Letter of Praise for his part in ‘Operation Neptune’, and the American Legion of Merit ‘for distinguished service during the planning and execution of the invasion of Normandy’ (Admiralty letter of notification, refers). An idea of the scale of his responsibilities in this period maybe be found in the inscription left by the Americans on a local commemoration stone: ‘The major part of the American Assault Force which landed on the shores of France on D-Day 6 June 1944, was launched from Portland harbour. From 6 June 1944 to 7 May 1945, 418,585 troops and 144,093 vehicles embarked from this harbour.’ Swabey was afterwards appointed Naval Officer in Charge at Leith, in which capacity he was awarded the K.B.E., the insignia for which he received at an investiture held on 28 January 1947. The Admiral, ‘a truly good man, kindly and modest, who feared God and honoured the King’, retired to Chichester and died there in February 1952. Sold with Buckingham Palace letter and invitation to attend Investiture on 28 January 1947; Bisley ‘Whitehead Challenge Cup’ medal, silver-gilt and enamels, hallmarked Birmingham 1905, with gilt enamelled ribbon bar ‘1905’ over wreath, and top suspension brooch, silver-gilt and enamel ‘NAVY’ surmounted by Naval crown, unnamed in B. Ninnes, Goldsmith, Hythe case of issue; together with studio portrait in uniform wearing medals and copied research

The unique Army of India medal awarded to Naval Schoolmaster H. J. Strutt, unique to this rank Army of India 1799-1826, 1 clasp, Ava (H. J. Strutt, Schoolmaster.) short hyphen reverse, officially impressed naming, sometime lacquered, otherwise nearly extremely fine and rare £1,800-£2,200 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Debenham Storr & Sons 1901; Christie’s, November 1982; Dix Noonan Webb, June 2005. H. J. Strutt is confirmed on the naval rolls for Ava as a Schoolmaster serving aboard H.M.S. Boadicea, the only such medal issued to this rare naval warrant rank. He was an Acting Schoolmaster until June 1826 when discharged upon promotion.

The campaign group of six awarded to Gunner E. N. A. Sayers, Royal Indian Marine, one of a small handful of Naval recipients of the Army G.S.M. for transport duties in the South Persia operations Naval General Service 1915-62, 1 clasp, Persian Gulf 1909-1914 (Gunr. E. W. Sayers, R.I.M.S. Minto) note initials but as per medal roll; 1914-15 Star (Gunner E. N. A. Sayers, R.I.M.); British War and Victory Medals (Gnr. E. N. A. Sayers. R.I.M.); General Service 1918-62, 1 clasp, S. Persia (Gnr. E. N. A. Sayers. R.I.M.); Jubilee 1935, one or two edge bruises and light contact wear, otherwise generally good very fine (6) £800-£1,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Edward Nelson Alleyn Sayers was born in Eastbourne, Sussex in September 1886 and joined the Royal Navy as a Boy 2nd Class in the course of 1903. Advanced to Ordinary Seaman in 1904, and to Able Seaman in 1905, he transferred to the Royal Indian Marine as a Gunner in late 1910. He served aboard the R.I.M.S. Minto in the Persian Gulf operations until October of the following year. Sayers next joined the Hardinge and remained in her for most of the Great War, seeing action against the Turks in 1915, when the latter attempted to block the Suez Canal. But it was while detached on transport duties to Bandar Abbas between late 1918 and the summer of 1919 that he qualified for his extremely rare G.S.M. Sayers was promoted to Boatswain in December 1922 and finally retired in October 1937. Sold with copied record of service and other research.

The rare Sudan campaign D.C.M. and Royal Marine M.S.M. group of five awarded to Colour Sergeant Frederick Evan Saddon, Royal Marine Artillery, for services at the battle of Gedid and during the final defeat of the Khalifa in November 1899 Distinguished Conduct Medal, V.R. (Col. Sejt. F. E. Saddon, R.M.A.) impressed naming; Queen’s Sudan 1896 (2602, Sgt. F. Evan Saddon, R.M.A.); Royal Navy L.S. & G.C., V.R., narrow suspension (F. E. Saddon, Col. Sergt. No. 2602 R.M.A.) impressed naming; Royal Marine Meritorious Service Medal, E.VII.R. (2602 F. E. Saddon, Colour Sergeant, R.M.A.); Khedive’s Sudan 1896-1908, 3 clasps, Khartoum, Gedid, Sudan 1899, unnamed as issued, light contact marks, otherwise very fine and better (5) £14,000-£18,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Frederick Evan Saddon was born in November 1865 at Portsea, near Portsmouth, Hampshire and was a tailor before enlisting at Eastney on 26 January 1886. On completion of Recruit Training at the Walmer Depot he was posted as a Private to the Royal Marine Artillery on 23 September 1886, and promoted to Gunner on 19 December 1886. He embarked aboard his first vessel H.M.S. Cyclops (July 1887), returned to the R.M.A. Depot (August 1887) and was next afloat aboard Neptune (March 1898) being promoted to Bombardier. In this rate he joined Galatea (July 1889) and Magicienne (April 1890) being promoted to Corporal on 11 July 1891. He returned to the R.M.A. Depot (August 1893) and next joined Victory for Royal Oak (June 1894), promoted to Sergeant 14 September 1894. He again served at the Depot (1894-98), prior to embarking for service with the Egyptian Army in June 1898, being promoted to Colour Sergeant on 25 October 1898. His service record states that he was mentioned in the despatch published in the London Gazette of 30 January 1900, and awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal in the London Gazette of 18 September 1900 ‘For services during the final defeat of Khalifa November 1899’. The action at Gedid on 22 November 1899 resulted in the final defeat of the Khalifa and Ahmed Fedil, both of whom were killed, and brought to an end the reconquest of the Sudan. The Royal Marine machine-gunners Seddon, Seabright and Sears all received the D.C.M. for their deadly and decisive work in this battle. A further note on his service record dated 4 April 1899 states ‘Noted by direction of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty for excellent service with the Nile Expedition 1898.’ He returned to the R.M.A. Depot in October 1900 and served ashore until discharged on 23 January 1907, having served for 21 years. He was awarded his L.S. & G.C. medal in February 1901, and the Royal Marine Meritorious Service Medal in 1907. Although nearly 50 years of age, he was called up for War service as a Colour Sergeant on 9 February 1915, but invalided ashore on 20 May 1916.

The superb campaign group of seven awarded to Paymaster Captain W. R. Dodridge, Royal Navy Ashantee 1873-74, no clasp (W. R. Dodridge. Clerk, R.N. H.M.S. Beacon. 73-74.); Egypt and Sudan 1882-89, dated reverse, 1 clasp, Alexandria 11th July (W. R. Dodridge. Ast. Paymr. R.N. H.M.S. “Cygnet”) rank officially corrected; India General Service 1854-95, 1 clasp, Burma 1885-7 (W. R. Dodridge, Asst. Paymr. R.N. H.M.S. Bacchante) officially impressed naming; Queen’s South Africa 1899-1902, no clasp (St. Paymr. W. R. Dodridge, R.N. H.M.S. Gibraltar.); British War Medal 1914-20 (Payr. Mr. in Ch. W. R. Dodridge. R.N.); Coronation 1911, unnamed as issued; Khedive’s Star, dated 1882, with Tokar clasp, unnamed as issued, mounted for display, good very fine or better, the last very rare (7) £2,600-£3,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Alan Hall Collection, June 2000. Approximately 14 Tokar clasps issued to Royal Navy officers, including 7 to H.M.S. Dolphin. William Reid Dodridge was born in Portsmouth, Hampshire, on 6 July 1853. He entered the Royal Navy as an Assistant Clerk in December 1870, was promoted to Clerk in December 1871, Assistant Paymaster in December 1874, Paymaster in June 1890, Staff Paymaster in June 1896, and Fleet Paymaster in June 1898. He reached the pinnacle of his profession on promotion to Paymaster in Chief in 1909, which rank was later changed to Paymaster Captain. He retired in 1911 after 40 years service including time spent on shore with Naval Brigades in Ashantee in 1873, in Burma during 1885 and in the Sudan in 1891. The rare aspect of this group is not in the 4 different campaign medals, which are however not common, but in the 'Tokar' Clasp on the Khedives Star. No British medal was issued for the action at Tokar in the Sudan, which took place on 19 February 1891. Those officers and men from H.M. Ships Dolphin and Sandfly became entitled to an undated Star and Clasp, or Clasp only if already in possession of a Star for previous service. Dodridge was Paymaster of Dolphin from September 1890 to October 1893, during which period the ship assisted the Egyptian Army with transport duties at Tokar. Recalled for service in World War I, he served on shore at President and Fisgard, and received the British War Medal. He died on 5 January 1928, aged 75. Sold with copied record of service.

Five: Commander Hon. Henry Baillie-Hamilton, Royal Navy, one of the small Naval Brigade to land in South Africa in 1851 South Africa 1834-53 (Midshipman H. Baillie.); Crimea 1854-56, 1 clasp, Sebastopol, unnamed as issued; Ottoman Empire, Order of the Medjidie, 5th class breast badge, silver, gold and enamel; Turkish Crimea 1855, Sardinian issue, unnamed; International, Sovereign Military Order of St. John of Jerusalem, Rhodes & Malta, Knight of Honour and Devotion neck badge, 110mm including crown and ribbon bow suspension x 52mm, silver-gilt and enamels, the second polished, otherwise nearly very fine or better (5) £2,400-£2,800 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Alan Hall Collection, June 2000. Only eight Royal Navy and two Royal Marine officers were landed in British Kaffraria in 1851 as part of a small Naval Brigade. Henry Baillie was born on 29 August 1832, the fourth son of George Baillie who, in 1859, became the 10th Earl of Haddington, and assumed the additional name of Hamilton as well as the Honourable title. He entered the Royal Navy as a 1st Class Volunteer in 1847 and in 1849 he was appointed to H.M.S. Castor, Commodore Christopher Wyvill, attached to the Cape of Good Hope Squadron. In 1851 he was a member of the 126 strong Naval Brigade landed to support the Army in South Africa. In a letter from Commodore C. Wyvill, dated 27 December 1851, he is recorded as having 'Behaved with the greatest credit whilst co-operating with the Army during the War in British Kafferia' and ordered to be noted for favourable consideration for promotion when he passes for Lieutenant. Appointed to the steamer Spiteful in 1853 and was present in the Black Sea during the first great bombardment of Sebastopol in which action he received a deep lacerated wound in the upper and back part of the thigh from a fragment of a rocket. He was gazetted on 3 November 1854, as having been severely wounded. He served aboard Spiteful throughout the entire Crimean campaign. On passing his examination he was promoted to Mate in February 1856. He received the Turkish and British Crimea Medals, the latter with clasp 'Sebastopol' and the Order of Medjidie 5th Class, being at the time one of the youngest officers to receive this honour. In November 1857 he was appointed Mate of the steamer Ardent, Commander John H. Cave, on the West Coast of Africa. In a letter of 11 February 1858, Rear Admiral the Hon Sir Frederick Grey, K.C.B., Commander in Chief Cape of Good Hope and West Coast of Africa reported favourably on his conduct whilst engaged with the Soosos Chief in operations on the Coast of Africa. In recognition of this service he was specially promoted to Lieutenant on 25 April 1858. In April 1859 he was appointed Lieutenant of Cresset, Steamer, Captain the Hon Charles Elliot C.B., Mediterranean, followed in 1862 by Imperieuse, Flag Ship East Indies and China, Rear-Admiral Sir James Hope K.C.B.; and in 1864 Victoria, Flag Ship Mediterranean, Vice Admiral Robert Smart K.C.B. K.H. On 6 January 1866, he was dismissed from Victoria by sentence of Court Martial and sentenced to lose one year's seniority as a Lieutenant. He was next appointed in June 1866 to the Royal George Captain Thomas Tiller, Coast Guard Service, Kingstown. In May 1869 he was severely reprimanded for slipping the anchor cable of Royal George on the occasion of the Whitsuntide Review. On paying off from Royal George in December 1869 he remained on shore until he retired at his own request on the 10 January 1871, with rank of Commander. He became a Justice of the Peace for Berwickshire and for philanthropic services he was created a Knight of Malta in 1883, dying in 1895.

The 2-clasp Naval General Service medal awarded to Rear-Admiral Alexander Montgomerie, Royal Navy, Lieutenant in the Sceptre at the destruction of the French 40-gun frigates Loire and Seine at Anse la Barque, and afterward in the operations leading to the reduction of the Island of Guadaloupe Naval General Service 1793-1840, 2 clasps, Anse la Barque 18 Decr 1809, Guadaloupe (Alexr. Montgomerie, Lieut. R.N.) toned, good very fine £5,000-£7,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Colin Message Collection, August 1999. Confirmed on the rolls as Midshipman aboard H.M.S. Sceptre at Anse la Barque, and as Acting Lieutenant of the Freija at the capture of Guadaloupe. 42 clasps issued for Anse la Barque. Alexander Montgomerie was born in London on 30 July 1790, the second son of the late Alexander Montgomerie, Esq., of Annick Lodge, co. Ayr (brother of Hugh, twelfth Earl of Eglinton, and grand-uncle of the present Peer), by Elizabeth, daughter of Dr. Taylor; and brother-in-law of the Right Hon. David Boyle, Lord Justice-Clerk. His brother, Hugh, married a daughter of Lieutenant-General Rumley, E.I.Co.’s service; and his grand-uncle, James, died a Lieutenant-General in the Army, 13 April 1829. His eldest brother, William Eglinton Montgomerie, Esq., of Annick Lodge, is Magistrate and Deputy-Lieutenant, and Lieutenant-Colonel Commandant of the Ayrshire Yeomanry Cavalry. This officer entered the Navy on 27 June 1802, as First-class Volunteer on board the Hazard sloop, Captain B. J. Neve, lying at Portsmouth; and from the following August until August 1808, was employed as Midshipman and Master’s Mate in the Argo 44, and Tigre 74, both commanded by Captain Benjamin Hallowell. In the Argo, after visiting the coast of Africa, he assisted at the reduction of Ste. Lucie and Tobago; and when in the Tigre, besides accompanying Lord Nelson to the West Indies in pursuit of the combined fleets of France and Spain, he participated in the operations of 1807 in Egypt, was present at the capture of Alexandria, and saw much boat service on Lake Mareotis. In September 1809, on passing his examination, he joined the Orpheus 36; and from that ship he was soon transferred to the Sceptre 74, Captain Samuel James Ballard, for a passage to the West Indies, where, on 18 of the ensuing December we find him contributing, in the boats of a squadron under the personal command of Captain Hugh Cameron, who was killed, to the destruction, in L’Anse la Barque, Guadeloupe, of the 40-gun frigates Loire and Seine, laden with stores, and protected by numerous strong batteries. As a reward for his conduct on the occasion, which was officially reported, he was nominated, the next day, Acting-Lieutenant of the Freija frigate, Captain John Hayes, an appointment the Admiralty confirmed by a commission dated 4 May 1810. Previously to that event Mr. Montgomerie, during the operations which led to the reduction of Guadeloupe, had been employed in the boats of his own ship and the Sceptre in destroying the various batteries erected on the island. After three months’ command of the Magnanime at Sheerness, he was appointed, 28 January 1811, to the Aquilon 32, Captains William Bowles and James Boxer, under whom he served for upwards of three years and a half on the North Sea, Baltic, and South American stations. When in the Baltic in 1812, and engaged with the boats under his orders in an attempt to bring some vessels off from the island of Rugen, he greatly distinguished himself by his conduct in capturing a temporary fort occupied by a superior number of troops, whom, on their being reinforced and endeavouring to recover their loss, he several times repulsed. On his return from the Rio de la Plata in September 1814, Mr. Montgomerie, who had been latterly First-Lieutenant of the Aquilon, found that he had been promoted to the rank of Commander on the 7th of the preceding June, and appointed to the Racoon sloop, which vessel, however, being at the time on the coast of Brazil, he never joined. He afterwards, 21 March 1818, assumed command of the Confiance 18, fitting for the West Indies, where he became, 13 July 1820, Acting-Captain of the Sapphire 26. He was confirmed 3 October following, and, in September 1821, he returned to England and was paid off. He accepted the Retirement on 1 October 1846, and was appointed Rear-Admiral retired on 2 March 1852. He died at Bridgend, Skelmorlie, Ayrshire, on 26 December 1863. Sold with copied record of service and extracts of Sceptre’s log for Anse la Barque.

The 3-clasp Naval General Service medal awarded to Commander John Taylor, Royal Navy, Midshipman of the Gibraltar at Egypt, and Master’s Mate and Lieutenant of the Donegal at St Domingo and Basque Roads Naval General Service 1793-1840, 3 clasps, Egypt, St. Domingo, Basque Roads 1809 (John Taylor, Master’s Mate.) fitted with contemporary silver top suspension brooch and contained in a fine contemporary fitted case, lightly polished, otherwise toned, nearly extremely fine £4,000-£5,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Confirmed on the rolls as Midshipman of H.M.S. Gibraltar at Egypt; and as Master’s Mate and Lieutenant of H.M.S. Donegal at St. Domingo and Basque Roads. John Taylor entered the Navy on 6 December 1794, as a Landsman on board the Scorpion gun-brig, Lieutenant-Commander Thomas Crocker, stationed off Jersey, from where he removed, in September 1795, to the Bravo 14, Captain Philip D’Auvergne. In May 1796 he became Midshipman of the Juste 80, Captains Hon. Thomas Pakenham and William Hancock Kelly, the latter of whom, after having served in the Channel, he followed, in May and June 1797, into the Veteran 64 and Gibraltar 80. In this latter ship, which was stationed off Cadiz and in the Mediterranean, he was nominated Acting-Lieutenant on 29 August 1801. Shortly afterwards, in March 1802, he was superseded and placed, once more as Midshipman, on board the Foudroyant 80, flagship of Lord Keith, with whom he returned shortly afterwards to England, and was paid off. Taylor was next employed in the Channel from May 1803 until June 1805, and then again in the Mediterranean in the Naiad 38, Captain James Wallis, and as Master’s Mate in the Royal Sovereign 100, bearing the flag of Sir Richard Bickerton. He was then transferred to the Donegal 74, under Captain Pulteney Malcolm, and in that ship, of which he was created a Lieutenant on 2 April 1806, he continued until March 1811. Consequently, Taylor assisted at the capture of the El Rayo of 100 guns, one of the ships recently defeated at Trafalgar; took part in the action off St. Domingo on 6 February 1806; escorted Sir Arthur Wellesley’s army from Cork to Portugal in 1808; witnessed the destruction on 24 February 1809, of three French frigates under the batteries of Sable d’Olonne; was present, in the following April, at Lord Cochrane’s destruction of the enemy’s shipping in Basque Roads; and shared in an unsuccessful attempt made by Captain Charles Grant of the Diana to destroy the two French frigates Amazone and Eliza, protected by the fire of several strong batteries near Cherbourg. The latter affair took place on the afternoon of 15 November 1810: during the night, Taylor, then First of the Donegal, was sent with two boats belonging to his own ship and the Revenge 74 to essay the effect of Congreve’s rockets on the enemy, and at daybreak on the 16th it was observed that one of the frigates was on her beam-ends and the other had run aground. After he left the Donegal, Taylor was successively appointed Senior, 13 August 1811 and 3 March 1812, of the Royal Oak 74, Captain P. Malcolm; of the Hannibal 74, Captains Samuel Pym and Sir Michael Seymour, both in the Channel; 13 June 1812 and 13 November 1813, of the Maidstone 36 and Romulus 36, armée en flûte, Captains George Burdett and George William Henry Knight, each on the North American station; and 17 May 1815 (after 14 months of half-pay) of the Falmouth 20, also commanded by Captain Knight, off Boulogne. Among other services of a similar character, he commanded the boats of the Maidstone and Spartan frigates at the destruction of the Morning Star and Polly, American privateers of 1 gun, 4 swivels, and 50 men each, in the Bay of Fundy on 1 August 1812; and two days later at the capture, in the same neighbourhood, of a well-armed custom-house cutter and four merchantmen. He remained in the Falmouth until 1 November 1812, and was placed on the list of Retired Commanders on 23 July 1839.

A most attractive campaign and life saving group of five awarded to Captain William Howorth, R.N., Inspecting Commander, H.M. Coastguard Penzance Baltic 1854-55 (W. Howorth, Mte. Comr. 2 Divn. M.V.); China 1857-60, no clasp (Lt. & Comr. W. Howorth, H.M.G.B. Weazel) fitted with replacement wire suspension rod; Royal Humane Society, large silver medal (successful) (William Howorth, Actg. Mate H.M.S. Blazer 24 Aug 1855); Royal National Lifeboat Institution, V.R., silver medal (Captain William Howorth, R.N. Voted 6th Feby. 1873); Norway, Medal for Brave Deeds, silver, the first three medals mounted on a triple brooch bar, as worn, all five medals have a frosted silvered finish and have been glazed in a fashion similar to the Army and Navy gold medals, glass lunettes cracked on the reverse of the Baltic medal and obverse of the Norwegian award, otherwise generally extremely fine (5) £3,000-£4,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- William Howorth was appointed a Naval Cadet in August 1847 and promoted Sub-Lieutenant on 22 October 1853; Lieutenant, 31 January 1856; Commander, 19 January 1867; Retired Captain, 3 February 1879. He served in the Baltic during the Russian war; several times engaged with pirates, in 1861-62, in China (China medal); has received “The Norwegian Medal for Civic Deeds.” His record of service notes: 20 August 1855, gazetted as having had charge of the Second Division of Mortar Vessels at the bombardment of Sweaborg. 3 October 1855, Vice Admiral Dundas especially reporting his gallant and noble conduct in jumping overboard and saving the life of a seaman. 31 October 1855. promoted to be an acting Lieutenant, his subsequent conduct having been favourably reported upon. 3 July 1861, Foreign Office enclosing thanks of the American Government for services rendered to the Leonidas ship. 9 December 1861 reporting that the Weazel had grounded through neglect, but that Lieut. Howarth being a very good and attentive officer he had only reproved him. 7 October 1871, Achilles additional for Coast Guard at Penzance. Royal Humane Society, silver medal: ‘24th August 1855 - Seized a life-buoy, jumped overboard, swam to Patrick Ryan, seaman, who had fallen into the sea off Gattland, and supported him until a boat arrived.’ Royal National Lifeboat Institution, silver medal, Voted 6 February 1873: William Howorth, Captain, R.N., Inspecting Commander H.M. Coastguard, Penzance. 26 January 1873: During a heavy southerly gale and high seas in Mount’s Bay, the Norwegian brig Otto was driven ashore at Eastern Green, Penzance Bay, Cornwall. The lifeboat Richard Lewis was launched through heavy seas, reached the wreck and took off the eight crewmen. 2 February 1873: When the seas were running very high, the French vessel La Marie Emilie of L’Orient ran ashore with waves rolling over her, and the lifeboat, in trying to get to her, was driven back twice and had seven oars broken. Two more attempts resulted in the lifeboat being dashed against the wreck each time, but on the third attempt all four crewmen were saved. Howorth received the Norwegian medal in recognition of his services to the Norwegian brig Otto on the above occasion. Captain Howorth died on 22 February 1881, his widow being granted a pension of £80 per annum.

The emotive Great War M.C. group of five awarded to Lieutenant-Colonel F. P. R. Nichols, Royal Army Service Corps, who died after nearly three weeks adrift in a lifeboat from the Cunard White Star Line’s Laconia, which ship, when torpedoed and sunk in shark-infested waters in the South Atlantic in September 1942, had 1800 Italian P.O.Ws aboard: upon learning of this, the U-Boat commander commenced rescue operations, but his admirable endeavours, and those of other U-Boats that joined the scene, were quickly curtailed by an unfortunate attack delivered by Allied aircraft - and the consequent transmittal of Admiral Donitz’s notorious “Laconia Order” Military Cross, G.V.R.; 1914 Star, with clasp (2. Lieut:F. P. R. Nichols. A.S.C.); British War and Victory Medals (Capt. F. P. R. Nichols.; Khedive’s Sudan 1910-21, 2nd issue, 1 clasp, Garjak Nuer, unnamed as issued, mounted as worn, very fine (5) £1,600-£2,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- M.C. London Gazette 1 January 1917. Francis Peter Ross Nichols was born in October 1892 and was commissioned into the Army Service Corps in February 1912. As a young officer he served with the B.E.F. out in France and Belgium between August 1914 and March 1915, and again between March 1916 and November 1918, gaining advancement to Captain in September 1917. After the War, between April 1919 and January 1925, Nichols was attached to the Egyptian Army, and was present in the Garjak Nuer operations of 1920. He was also attached, between January 1925 and April 1929, to the Sudan Defence Force. And by the renewal of hostilities he had risen to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. For exactly what reasons Nichols found himself aboard the Laconia in September 1942 remains unknown, but the 49-year old Colonel would have joined her at either Suez or the Cape, from which ports she continued her homeward bound voyage with some 2700 people aboard. A few of these passengers no doubt constituted the reason behind her wartime role as an Admiralty-requisitioned troopship, Nichols among them, but 1800 of them were actually Italian P.O.Ws, under a 160-strong Polish guard. On 12 September 1942, in a position about 500 miles south of Cape Palmas, Liberia, the Laconia was torpedoed and sunk by the U-156, commanded by Kapitain Werner Hartenstein. Shortly after the liner capsized, the crew of the now surfaced U-Boat were amazed to hear Italian voices yelling amongst the survivors struggling in the water, and on speaking to some of them, Werner Hartenstein immediately began rescue operations, alerting at the same time nearby U-Boats to come to his assistance. Also by radio he contacted his seniors in Germany, asking for instructions and, more courageously, sent out an uncoded message inviting any nearby ships to assist, allied or otherwise, promising not to attack them on the basis his U-Boat, too, was left unmolested. And amazingly, to begin with at least, Berlin replied in the affirmative, although Hitler personally intervened to threaten Admiral Raeder in the event of any U-Boats being lost to enemy action as a result of the rescue operation. Over the next few days, Hartenstein’s ‘rescue package’ achieved commendable results, and by 16 September, U-156 had picked up around 400 survivors, half of which she towed astern in lifeboats, while other enemy U-Boats, the U-506 and the U-507, and the Italian Cappellini, had arrived on the scene and acted with similar compassion. Tragically, on 16 September, an American Liberator bomber, operating out of Ascension Island, attacked the gathered U-Boats and Cappellini, forcing Hartenstein and his fellow captains to cut their tows with the lifeboats and submerge. Mercifully, some neutral (Vichy) French warships arrived on the scene soon afterwards from Dakar, and in total, including those still aboard the U-Boats, some several hundred men, women and children were saved. But two lifeboats remained undiscovered, their occupants having to endure a living nightmare, adrift without adequate sustenance, under a burning sun, with sharks for company, for several weeks. One of those lifeboats became the final refuge of Nichols, who valiantly battled on for nearly three weeks before finally succumbing to the elements. Thanks to the account of a survivor from the same boat, Doris Hawkins, a moving picture emerges of the Colonel’s last days, and how he displayed no small degree of leadership and courage under the most appalling circumstances. For there can be little, if any, doubt that he is the Army Officer referred to in her account, given the combination of his rank and date of death, specifically recorded by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission as 30 September, and not the actual date of the Laconia’s loss. To begin with, assisted by Laconia’s young surgeon, Dr. Purslow, he assumed responsibility of the the daily rations and water supply for the 68 unfortunates crammed into the 30 foot lifeboat, which had a leak which necessitated pumping day and night. Those rations comprised in the morning of ‘four or five Horlicks tablets and three pieces of chocolate’ (and no water), and in the evening of ‘two ship’s biscuits, one teaspoonful of pemmican and two ounces of water’. Inevitably, extra space soon became available in the lifeboat, and those who were committed to the deep probably encouraged the sharks that followed it with ‘uncanny knowledge’. Miss Hawkins, who was a trained nurse, felt completely helpless as a result of the total lack of medical supplies, a dreadful variety of painful infections and other illnesses being brought on by starvation, lack of water and constant exposure to the elements. Morale, too, began to falter, as each day and night passed, Hawkins recording how the Colonel did his best to raise hopes on the 27th, after everyone fell silent when a three-funnelled vessel passed them by from a distance of about four miles in the morning: ‘That was a silent day. Towards evening, as the Colonel was about to help serve the rations, he spoke to us all: “listen, everyone,” he said, “We have had a big disappointment today, but there’s always tomorrow. The fact we have seen a ship means that we are near a shipping route, and perhaps our luck will turn now. Don’t lose hope because of what happened this morning.” ’ By this stage, with no water left, deaths were common place among the dwindling survivors, and although Hawkins makes no specific reference to the Colonel’s passing, it seems likely that she was responsible for recording his date of demise as the 30 September. As stated, and most unusually, that is the date cited by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, whose archives even have a reference to the Colonel having been in a lifeboat. Hawkins and a few others lived to reach Liberia on 8 October 1942, the former stating in the final chapter of her subsequent and moving story: “We who survived will remember some whose patience, tact and courage was an inspiration.” Undoubtedly among those in her thoughts was the gallant Colonel, who is commemorated on the Brookwood Memorial in Surrey and who left a widow, Evelyn Aubre Nichols. Note Following his enforced departure from the scene of rescue on 16 September, Kapitain Hartenstein remained in contact with Berlin, in a vain attempt to complete his worthy task. In the event, he, and his fellow U-Boat commanders, received Donitz’s famous “Laconia Order”, a diktat that mercilessly rewrote the conduct of sea warfare (and cost the Grand Admiral dearly at Nuremberg): 1. Every attempt to save surviv...

The outstanding group of five awarded to The Reverend Edward A. Williams, Chaplain of the Pearl in the Indian Mutiny, being frequently mentioned in despatches; he was author of ‘The Cruise of the Pearl round the World, with an account of the operations of the Naval Brigade in India’, published in 1859 Baltic 1854, unnamed as issued; Indian Mutiny 1857-59, no clasp (Rev. Edwd. A. Williams, Chaplain. Pearl.); Jubilee 1887 with bar 1897; Coronation 1902; Coronation 1911, light contact marks to the first two, otherwise good very fine and better (5) £4,000-£5,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Douglas-Morris Collection, Dix Noonan Webb, October 1996. Edward Adams Williams was born on 26 March 1826, the second son of Henry Williams of Glasthule, Co Dublin, whose ancestor settled at Rath Kool when William III carried on a successful campaign in Ireland. His mother, née Esther McClure, was a descendant of two Huguenot families, de la Cherois and Crommeline, who were invited by William III to settle in County Antrim and improve the damask manufactures. He graduated from Trinity College, Dublin, in 1848, obtaining the Divinity Testimonial. Ordained by the Bishop of Worcester and subsequently, in 1849, given the curacy of Lye, Worcestershire. He joined the Royal Navy when appointed as the Chaplain of H.M.S. St George on 3 March 1854, seeing service in the Baltic campaign of 1854. He received the additional rank of Naval Instructor on 25 April 1855, and a month later was re-appointed to H.M.S Hawke as her "Chaplain & Naval Instructor", and was present at the attack on the forts in the Gulf of Riga during 1855, earning the Baltic Medal. He was appointed as the ship's Chaplain to H.M.S. Pearl on 3 May l856, and served the whole time ashore with Pearl’s Naval Brigade prior to being ‘paid off’ on 15 January 1859. From 27 November 1857 Pearl’s Naval Brigade became the only wholly European manned part of the Sarun Field Force. The Reverend Williams was Mentioned in Despatches on the following occasions: by Captain E. S. Sotheby, R.N., in letters dated 28 December 1857, 1st March, 9th March and 29th April 1858, and also by Colonel F. Rowcroft, Commanding Sarun Field Force, on 22nd February and 6th March 1858. He subsequently served aboard H.M. Ships Royal Adelaide, Reserve Depot Ship, Devonport (1860-62), and Impregnable, Training Ship, Devonport (1862-64). His final sea appointment was aboard H.M.S. Cadmus on the North America and West Indies Station commencing 28 February 1865. His last naval appointment was to H.M.S. Excellent, Gunnery Training Ship at Portsmouth, on 4 April 1868. In 1872 he was appointed Secretary of the Church Missionary Society for the Metropolitan District. From 6 March 1875 he became the Chaplain serving with the Royal Marine Artillery, Portsmouth, until 19 May 1880, when he was transferred to Sheerness Dockyard as the Chaplain for 18 months prior to serving in a similar capacity in Portsmouth Dockyard until retired in 1886 as the senior Chaplain, but not chosen to be the Chaplain of the Fleet. He received the appointment as Honorary Chaplain to Queen Victoria in 1898, retaining this similar honour to Edward VII and George V until he died at 5 Queen's Gate, Southsea on 13 April 1913 aged 87 years. He was buried at Highland Road Cemetery, Southsea on 16 April, but due to the inclement weather, with agreement of his relatives, the event was to a large extent shorn of the ceremonial element. The coffin of polished oak, covered with a Union Jack, upon which was placed his stole, war medals and coronation honours and his badge as Honorary Chaplain to the King, was borne to the cemetery on a naval field-gun carriage drawn by bluejackets. It was preceded by a Naval firing party, who fired three volleys above his grave witnessed by mourners, who included a few veterans from the Crimean War and Indian Mutiny. The ceremony ended with a Naval bugler sounding the ‘Last Post’. Williams was author of The Cruise of the Pearl round the World, with an account of the operations of the Naval Brigade in India, published in 1859. Concerning the landing of the Naval Brigade, Williams claimed: ‘This is, I believe, the only example of the Royal Navy leaving their ships, and taking their guns seven or eight hundred miles into the interior of a great continent, to serve as soldiers, marching and counter-marching for fifteen months through extensive districts, and taking an active part in upwards of twenty actions.’ Of the thirteen chapters of the book, eleven relate to the activities of the Naval Brigade. Prior to the ship’s arrival at Calcutta on 12 August 1857, she had spent over a year after leaving England on a voyage which included the passage of the Strait of Magellan, the punishment of Peruvian revolutionaries who had plundered a British ship, and visits to the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) and Hong Kong, where the Pearl stayed only a month before being ordered to Calcutta. Thereafter Williams faithfully chronicled the movement up country of the Naval Brigade and the actions which it fought under Captain Sotheby’s immediate command and in support of Indian Army units, but he had little to say concerning his own duties as chaplain: ‘After parade came daily prayers, for the men of the Naval Brigade, which lasted about ten minutes. This custom not being unusual on board a “man-of-war” was continued throughout the campaign.’ He spoke of the war as “brutalising, in which quarter was neither given nor received. No European that fell into their hands could expect anything but a most cruel death... and therefore prisoners were not taken.” Williams was formerly Hon Editor of the Anchor Watch, and the last survivor of the founders of the Royal Naval Scripture Reader's Society, of which he had been the first Honorary Secretary when it was inaugurated at Devonport in 1860.

The Second War ‘Fall of Singapore’ D.S.M. group of six awarded to Stoker P. A. H. Dunne, Royal Navy, for a motor launch versus Japanese destroyer action of “Li Wo” proportions: few escaped the resultant carnage inflicted by several point-blank hits on H.M.M.L. 311’s hull and upper deck and those that did had to endure over four years as a P.O.W. of the Japanese, the wounded Dunne amongst them Distinguished Service Medal, G.VI.R. (Sto. P. A. H. Dunne, P/KX 132616); 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; Pacific Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, mounted as worn, minor contact marks, good very fine or better (6) £4,000-£5,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- D.S.M. London Gazette 19 February 1946: ‘For great gallantry, although wounded, in keeping the engine room services of H.M.M.L. 311 in action after an attack by a Japanese destroyer on 15 February 1942.’ The original recommendation states: ‘During the engagement between H.M.M.L. 311 and a heavy Japanese destroyer on 15 February 1942, when the remainder of the Engine Room personnel had been killed, and heavy damage sustained in the Engine Room, the above rating continued to keep the Engine Room services in action, under the most trying conditions. Throughout the engagement, being himself wounded in the leg, Stoker Dunne worked in close proximity to blazing petrol tanks, and in additional danger from pans of live Lewis gun ammunition bursting into flames, some of which penetrated the Engine Room. He remained carrying out E.R. duties until the order to abandon ship was received.’ Percy Albert Holmes Dunne, a native of Whitley Bay, Northumberland, who was born in November 1921, was recommended for his immediate D.S.M. by Commander V. C. F. Clarke, D.S.C.*, R.N., in October 1945, when the latter, the senior surviving officer from H.M.M.L. 331, submitted his official report of the action to Their Lordships: ‘I have the honour to submit the following report of the passage of H.M.M.L. 311 from Singapore to Banka Straits and her sinking there by enemy action. This report is forwarded by me, as Senior Naval Officer on board, in the absence of her Commanding Officer, Lieutenant E. J. H. Christmas, R.A.N.V.R., whose subsequent fate is unknown. I embarked on H.M.M.L. 311 on the afternoon of 13 February 1942, as a passenger. Orders were later received from R.A.M.Y., through Commander Alexander, R.N., to embark about 55 Army personnel after dark, then proceed to Batavia via the Durian Straits ... At daylight on the 15th, we sighted what appeared to be a warship from 2 to 3 miles distant, almost dead ahead, in the swept channel, at a fine inclination, stern towards us and to all appearances almost stopped. We maintained our course, being under the impression that this was probably a Dutch destroyer. When about a mile away the destroyer altered course to port and was immediately recognised by its distinctive stem as a Japanese destroyer of a large type. At Lieutenant Christmas’ request, I took command of the ship and increased to 18 knots, maintaining my course, to close within effective range. The enemy opened fire and, with the first salvo, scored two hits, one of which penetrated the forecastle deck, laying out the gun’s crew, putting the gun out of action and killing the helmsman. Lieutenant Christmas took the wheel, and I increased speed to approximately 20 knots, and made a four-point alteration of course to starboard to open ‘A’ arcs for the Lewis guns, now within extreme range. This brought me on a course roughly parallel and opposite to the enemy enclosing the Sumatra shore, which, in the almost certain event of being sunk, should enable the crew and the troops to swim to the mainland. On my enquiring, after the alteration, why the 3-pounder was not firing, I was informed it was out of action. By constant zig-zagging further direct hits were avoided for a short time, during which the light guns continued to engage the enemy. The enemy, however, having circled round astern of me, was closing and soon shrapnel and direct hits began to take their toll both above and below decks. The petrol tanks were on fire, blazing amidships, and there was a fire on the messdecks. The engine room casing was blown up and two out of three E.R. personnel had been killed, whilst the third, a Stoker [Dunne], was wounded in the leg. The port engine was put out of action. The E.R. services as a whole, however, were maintained throughout the action. Finally, Lieutenant Christmas at the helm reported the steering broken down with the rudder jammed to starboard. We began circling at a range of about 1000 yards. Further offensive or defensive action being impossible, with all guns out of action and the ship ablaze amidships, I stopped engines and ordered ‘abandon ship’. Casualties were heavy. I estimate that barely 20 men, including wounded, took to the water. The Japanese destroyer lay off and, although the White Ensign remained flying, ceased fire but made no attempt to pick up survivors. I advised men to make for the mainland shore but a number are believed to have made for the middle of the Strait in the hope of being picked up. The action lasted about ten minutes. The captain of the Mata Hari (Lieutenant Carson), who witnessed the action, states that the Japanese ship fired 14 six-gun salvoes. There were four, or possibly five, direct hits, and, in addition to the damage from these, most regrettable carnage was caused on the closely stowed upper deck by bursts from several “shorts”. The ship sank not long after being abandoned, burning furiously.’ Other than Dunne, no other officer or rating appears to have been decorated for the action, Clark’s D.S.C. and Bar having stemmed from acts of gallantry in the Second Battle of Narvik and during earlier air attacks off Singapore; sadly the fate of Lieutenant E. J. H. Christmas, R.A.N.V.R., was never fully established, and he is assumed to have died on 15 February 1942. Sold with the recipient’s original Buckingham Palace returning P.O.W’s message, dated September 1945, together with a quantity of related research, including copied recommendation, Japanese POW card, and a copy of Commander Victor Clark’s memoirs, Triumph and Disaster, in which he describes the demise of H.M.M.L. 311 in detail.

The important Second War K.C.B., C.B.E., Royal Visit M.V.O. group of twenty-one awarded to Admiral Sir William Tennant, Royal Navy After playing a pivotal role in Operation ‘Dynamo’ in 1940, when he was the Senior Naval Officer ashore at Dunkirk and the last to depart the beleaguered port, he likewise played a vital role in the planning and execution of Operation ‘Neptune’ in 1944, not least in the deployment of the Mulberry Harbours and ‘Pluto’ pipelines In the interim, he served as captain of H.M.S. Repulse in the Far East, up until her famous loss to Japanese aircraft in 1941, on which unhappy occasion he determined to go down with his ship, but three of his officers pushed him bodily off the bridge and over the side The Most Honourable Order of the Bath, K.C.B. (Military) Knight Commander’s set of insignia, comprising neck badge, silver-gilt and enamels; and breast star, silver, with gold and enamel appliqué centre; The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, C.B.E. (Military) Commander’s 2nd type neck badge, silver-gilt and enamels; The Order of St. John of Jerusalem, Knight of Grace’s set of insignia, comprising neck badge and breast star, silver and enamel; The Royal Victorian Order, M.V.O., Member’s 4th Class breast badge, silver-gilt and enamels, the reverse numbered ‘1189’; 1914-15 Star (Lieut. W. G. Tennant, R.N.); British War and Victory Medals (Lieut. W. G. Tennant. R.N.); Naval General Service 1915-62, 1 clasp, Palestine 1936-1939 (Capt. W. G. Tennant. M.V.O. R.N.); 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; Africa Star, 1 clasp, North Africa 1942-43; Pacific Star; Italy Star; War Medal 1939-45; Jubilee 1935; Coronation 1937; Coronation 1953; France, Third Republic, Legion of Honour, Officer’s breast badge, silver-gilt and enamels; Croix de Guerre 1939, with palm; Greece, Kingdom, Order of George I (Military), 2nd Class set of insignia by Spink, London, comprising neck badge and breast star, silver-gilt and enamels, red enamel in centre of badge badly chipped; United States of America, Legion of Merit, Commander’s neck badge, silver-gilt and enamels, suspension loop numbered ‘385’, mounted court-style where appropriate, together with related mounted group of twenty miniature medals (not including Greek Order), generally good very fine or better (24) £8,000-£10,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Spink, December 1997, when the Greek insignia was incorrectly described as that of the Order of the Phoenix. K.C.B. London Gazette 18 December 1945: ‘For distinguished service throughout the War in Europe.’ C.B. London Gazette 7 June 1940: ‘For good services in organising the withdrawal to England under fire and in the face of many and great difficulties of 335,490 officers and men of the Allied Armies, in about one thousand of His Majesty’s Ships and other craft between the 27th May and 4th June 1940.’ The original recommendation states: ‘For distinguished service as Senior Naval Officer on shore at Dunkirk during the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force and part of the French Army. His excellent liaison with the French authorities enabled the drawn-out process of embarkation, both from the breakwater and the beaches, to be carried out to the best possible advantage. This work was carried on throughout the whole period of nine days under the strain of continuous bombardment both from the air and land.’ C.B.E. London Gazette 28 November 1944: ‘For distinguished services in operations which led to the successful landing of Allied Forces in Normandy.’ The original recommendation states: ‘Rear-Admiral Tennant was the Flag Officer placed in charge of the operations connected with the construction of the artificial harbours and craft shelters, known collectively as ‘Mulberries’ and ‘Gooseberries’. Nothing of this extent and nature has ever before been attempted, even in times of peace, and for the work to be successful called for great powers of organisation, combined with initiative, resource and seamanlike skill of a very high order, all of which was forthcoming in full measure. In addition to this task Admiral Tennant was charged with the responsibility for co-ordinating all the multifarious towing requirements connected with the operation, extending over a period of several months, as well as for other tasks in all of which he was supremely successful. His tact, patience and charm of manner overcame many difficult situations and gained of him the universal support of the heterogeneous collection of individuals comprising the organisations which he had formed and over which he so effectively presided. I have no hesitation in stating that the very satisfactory maintenance of the Allied Armies in France was due in large measure to the successful work of Admiral Tennant and his organisation.’ M.V.O. London Gazette 10 November 1925: ‘On the occasion of the visit of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales to Africa and South America.’ Greek Order of George I London Gazette 15 April 1947: ‘For valuable services to the Royal Hellenic Navy during the war in Europe.’ U.S.A. Legion of Merit London Gazette 15 October 1946: ‘For services to the United States of America during the war.’ His French Legion of Honour and Croix de Guerre are also verified and were for services on the Staff of the C.-in-C. of the Allied Expeditionary Force in the liberation of France. The original recommendation (ADM 1/16697) states: ‘As a member of Admiral Sir Bertram H. Ramsay’s staff, he played an important part in the preparation and, especially, in the execution of the operations of disembarkation in Normandy on 6 June 1944 and the days immediately following, thus effectively participating in the liberation of a portion of French territory.’ William George Tennant was born at Upton-on-Severn on 2 January 1890, the son of an army officer, and was educated at Hanley Castle Grammar School prior to entering the Royal Navy as a Cadet in Britannia in May 1905. Subsequently confirmed in the rank of Sub. Lieutenant in December 1909, and advanced to Lieutenant in June 1912, he specialised in navigation. During the Great War he served in the Harwich Force, in the destroyers Lizard and Ferret, and afterwards in the Grand Fleet in the cruisers Chatham and Nottingham, and he was present at the latter’s loss on 19 August 1916, when she was torpedoed in the North Sea by the U-52, with a loss of 38 men. Having ended the war in the cruiser Concord, Tennant was next appointed to the royal yacht Alexandra, in which role he made a good impression, for, in September 1921, as a recently promoted Lieutenant-Commander, he joined the battle cruiser Renown as navigating officer for the Prince of Wales’s royal tour to India and Japan. That too clearly went well, for he was subsequently appointed navigating officer of the Repulse for the Prince’s tour to Africa and South America in 1924-25. He was advanced to Commander and appointed a Member of the Royal Victorian Order (M.V.O.). Royal service aside, Tennant gained valuable experience in the Operations Division of the Admiralty in the mid-20s, toured the Mediterranean as executive officer of the cruiser Sussex in 1929-30, and was advanced to Captain on the staff of the R.N.C. Greenwich in December 1932. Another tour in the Mediterranean having ensued, in command of the cruiser Arethusa, he was appointed Chief Staff Officer to First S...

Naval General Service 1793-1840, 1 clasp, 11 Aug Boat Service 1808 (Wm. Raddon.) a little polished, otherwise nearly very fine £6,000-£8,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Cheylesmore Collection, Glendining’s, July 1930; Spink, July 2000. William Raddon is confirmed on the roll as an Able Seaman aboard the Edgar for the Boat Service action of 11 August 1808, one of just 15 recipients of this clasp recorded on the Admiralty roll. Awarded for the capture of the Danish Corvettes Fama and Salorman by boats from Rear-Admiral Richard Keats’ Squadron, in Nyborg Harbour, Funen Island, Denmark, an action that actually took place on 9 August 1808. ‘At the time of the uprising of the Spaniards against the oppressive rule of the French in 1808, a body of about twelve thousand Spanish troops under the command of the Marquis de la Romana, were stationed on the shores of the Baltic, with the alleged intention of invading Sweden, in conjunction with a Danish army. On learning the state of affairs in Spain, these troops swore to be faithful to their country, and were eager to join their countrymen to assist in overthrowing the tyrant to whom they owed their banishment. A small British squadron was cruising in the Cattegat, commanded by Rear-Admiral Keats, in the Superb, seventy-four, comprising the Brunswick, seventy-four, Captain T. Graves; the Edgar, seventy-four, Captain J. Macnamara, and five or six smaller vessels. According to a plan concerted between the Rear-Admiral and the Marquis de la Romana, the latter on August 9th took possession of the fort and town of Nyborg, on the island of Funen. The Admiral then wrote to the Danish governor, engaging to abstain from any act of hostility if the Spaniards were unmolested by the Danish or French troops, but stating that if any opposition was offered to the embarkation of the Spanish troops, the town of Nyborg would probably be destroyed. The Danish garrison made no resistance, but the Danish eighteen-gun brig Fama, and a twelve-gun cutter, moored in the harbour near the town, rejected all offers, and prepared for action. The Spanish General being unwilling to act against the Danes, and the capture of the vessels being absolutely necessary, some small vessels and boats, under the orders of Captain Macnamara, entered the harbour, and attacked and carried both the vessels, with the loss of Lieutenant Harvey of the Superb, killed, and two men wounded. A few days afterwards ten thousand Spaniards were conveyed to England, and subsequently to their native country.’ (Medals of the British Navy, by W. H. Long refers.)

The important Great War Q-Ship commander’s D.S.O. and Bar group of seven awarded to Captain S. H. Simpson, Royal Navy, who was twice decorated for his command of the Q-Ship Cullist from March 1917 to February 1918, a period that included no less than five close encounters with enemy submarines, the last of them resulting in Cullist’s demise Distinguished Service Order, G.V.R., with Second Award Bar, silver-gilt and enamels, with integral top riband bar; 1914-15 Star (Lt. Commr. S. H. Simpson, R.N.); British War and Victory Medals, with M.I.D. oak leaves (Lt. Commr. S. H. Simpson. R.N.); Defence and War Medals 1939-45; France, 3rd Republic, Croix de Guerre 1914-1917, with bronze palm, mounted as worn, minor enamel chips to wreaths of the first, generally good very fine and better (7) £10,000-£14,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Douglas-Morris Collection, Dix Noonan Webb, October 1996; R. C. Witte Collection, Dix Noonan Webb, December 2007. D.S.O. London Gazette 29 August 1917: ‘For services in action with enemy submarines.’ D.S.O. Second Award Bar London Gazette 22 February 1918: ‘For services in action with enemy submarines.’ French Croix de Guerre London Gazette 17 May 1918. Salisbury Hamilton Simpson was born in Karachi in September 1884, the son of a half-Colonel in the Indian Army, and entered the Royal Navy as a Naval Cadet in Britannia in January 1900. Appointed a Midshipman in the battleship Jupiter in the Channel Squadron in June 1901, he was advanced to Lieutenant in April 1907, and was serving in the cruiser Argyll in that rank on the outbreak of hostilities in August 1914. Removing to his first command, the sloop Jessamine, in early October 1915, he informed his Admiral that he would need a week to get the ship seaworthy - the latter coldly informed him to proceed to sea at 8 a.m. the following morning. Thus ensued an eventful commission, Chatterton’s Danger Zone quoting some of Simpson’s operational reports. But it was his transfer to Queenstown Command in March 1917 that led to his many honours, for, in the same month, he was appointed to the command of the Cullist (ex-Westphalia), a Q-Ship armed with one 4-inch gun, two 12-pounders and two torpedo tubes. Between then and February 1918, Simpson was involved in no fewer than five actions, the last of them resulting in Cullist’s demise: On 13 July 1917, while sailing between the French and Irish coasts, an enemy submarine was sighted on the surface at 11,000 yards range, from which distance it began shelling the Cullist. After firing 38 rounds without recording a hit, the enemy was enticed by Simpson’s tactics to close the range to 5,000 yards, and fired a further 30 rounds, some of which straddled their target. At 1407 hours Cullist returned fire, her gunners getting the range after their second salvo was fired and numerous hits were recorded on the enemy’s conning tower, gun and deck. Then an explosion was seen followed by bright red flames, and three minutes after engaging the submarine it was seen to go down by the bows leaving oil and debris on the surface - the latter included ‘a corpse dressed in blue dungarees, floating face upwards.’ Simpson was awarded the D.S.O. On 20 August 1917, in the English Channel, an enemy submarine was sighted on the surface and opened fire on the Cullist at 9,000 yards range. After 82 rounds had been fired by the submarine, just one of them scored with a hit on the water-line of the stokehold, the shell injuring both the firemen on watch and causing a large rush of water into the stokehold, which was overcome by plugging the hole and shoring it up. Several time-fuzed shrapnel projectiles were also fired at the Cullist but without effect. The submarine then closed the range to 4,500 yards at which time the Cullist returned fire and scored two hits in the area of the conning tower, upon which the submarine was seen to dive and contact was lost. On 28 September 1917, in another hotly contested action, Simpson gave the order to open fire on an enemy submarine at 5,000 yards range - ‘thirteen rounds were fired of which eight were direct hits, causing him to settle down by the bowstill while about 30 feet of his stern was standing out of the water at an angle of about 30 degrees to the horizon. He remained in this position for about ten to fifteen seconds before disappearing at 12.43 hours.’ Soon afterwards Simpson spotted another enemy submarine and set off in pursuit, on this occasion to no avail. Yet another brush with the enemy took place on 17 November 1917, when the Cullist was sighted by an enemy submarine which opened fire at 8,000 yards range. Within five minutes the enemy had the range and a shell glanced off the Cullist’s side, damaging one of three officers’ cabins before bursting on the water-line. After disappearing in a bank of fog the submarine re-appeared and continued to shell the Cullist with such accuracy that for 50 minutes the decks and bridge were continually sprayed with shell splinters and drenched with water from near misses. In all, the enemy fired 92 rounds, while the Cullist returned fire from 4,500 yards, 14 rounds being fired at the submarine of which six were seen to be direct hits. The submarine, although badly damaged, was able to turn away, dive and escape. Simpson was awarded a Bar to his D.S.O. On 11 February 1918, however, the Cullist’s luck ran out and she was torpedoed without warning in the Irish Sea and sank in two minutes. The enemy submarine then surfaced and asked for the Captain, but was told that he had been killed. The Germans then picked up two men and after verbally abusing the remaining survivors, made off. Simpson, who had been wounded, was pulled into one of the rafts, and the survivors were subsequently rescued by a patrol trawler, but not before being forced to sing “Tipperary” to convince the trawlermen of their true identity. Simpson was mentioned in despatches (London Gazette 22 February 1918), but such was the nature of his wounds, which included a ‘broken shoulder’, that he did not obtain another seagoing command until joining H.M.A.S. Anzac in September 1919, shortly after his advancement to Commander. In late 1924, he assumed command of the Widgeon in the Far East, taking over from Commander M. G. B. Legge, D.S.O., and in August of the following year he became S.N.O. on the Upper Yangtze, winning Their Lordships’ appreciation for his services during ongoing local disturbances. His First Lieutenant during this period was Lieutenant (afterwards Rear-Admiral) A. F. Pugsley, the author of Destroyer Man, a work in which he refers to his C.O’s gathering apathy, rather than the more charming eccentricity for which he was known in his Q-Ship days, and therein, no doubt, lay the roots of Simpson’s request to be placed on the Retired List in December 1930. Recalled on the renewal of hostilities, he served as a Divisional Sea Transport Officer at Plymouth, Belfast and Glasgow, and was released in March 1946. Simpson died in January 1951.