We found 70379 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 70379 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

70379 item(s)/page

OBVERSE: In field: Armoured bust to right, holding sheathed sword in right hand, with name of the Sasanian ruler Khusraw in Pahlawi to right and gdh apzwt (‘may his glory increase’) to left. In border: bismillah la i- laha illa Allah wa – hdahu Muhammad ra – sul Allah, divided by stars-in-crescents except above the bust, where the star-in-crescent is replaced by a pellet-within-annulet. REVERSE: In field: Arch supported on columns, within which is a vertical barbed spear which has two pennants floating to the left just below the head; to right and left of the columns: khalifat Allah - amir al-mu’minin; to either side of the spear-shaft: nasr – Allah. In border: Four stars-in-crescents, with Pahlawi ap (‘praise’) at one o’clock. WEIGHT: 3.54g. REFERENCES: Treadwell 2005, 2 same dies; Walker p.24, ANS.5, same reverse die = Gaube 2.3.2.4. CONDITION: Very fine to good very fine, excessively rare and a type of considerable historical significance. One of the greatest and most sought-after rarities of the Arab-Sasanian series, the ‘Mihrab and ‘Anaza’ drachm has been rightly described as ‘extraordinary’ (Grabar, O., The Formation of Islamic Art, revised and enlarged edition, Yale, 1987), and ‘a very valuable little archaeological document’ (Miles, ‘Mihrab and ‘Anazah’). Many of the difficulties of interpreting this piece stem from the fact that it lacks both date and mint-name. Most scholars have assumed that it was struck at Damascus. Firstly, the mean weight of extant specimens is about 3.6-3.7g, which is somewhat lighter than the standard maintained at mints in the East but consistent with other Arab-Sasanian issues struck at Damascus in the early-mid 70s. Secondly, Damascus was the Umayyad capital where other experimental drachms were struck, including the Standing Caliph type with which the Mihrab and ‘Anaza drachms have often been compared. This may very well be correct, although it will be suggested below that other possibilities should also be considered. The latest study of this issue is that of Treadwell (2005), who plausibly interprets the imagery on this coin as a reaction to perceived problems with the design of the Standing Caliph drachms, which he argues must have been struck immediately before the Mihrab and ‘Anaza type. On this analysis, the Standing Caliph type was produced to accompany the Standing Caliph dinars and fulus introduced in Syria in the previous year. Treadwell notes that the gold and copper issues conformed to ‘the traditional numismatic formula that located the ruler on the obverse and a religious symbol on the reverse,’ while the ‘Standing Caliph’ drachm ‘contained two conflicting images of rulership…it is the Shahanshah’s imposing bust that dominates the imagery of the coin, not the cramped figure of the caliph on the reverse’ (Treadwell, p.11). The Mihrab and ‘Anaza type rectifies this by changing the design of the Sasanian bust so that it is recognisably the Caliph who appears on the obverse, and by replacing the standing figure on the reverse with an image of the Prophet’s spear mounted within an arch. Unfortunately, while this argument neatly explains the imagery, it clashes awkwardly with the legends. The bust which Treadwell identifies as the caliph himself is in fact labelled in Pahlawi as that of Khusraw, while the spear on the reverse carries the legends khalifat Allah – amir al-mu’minin. It is possible to argue, as Treadwell does, that ‘the Standing Caliph drachm was an unsuccessful hybrid that had been cobbled together at speed [and so] it would not be surprising if its hastily executed substitute were also deficient in some respects.’ But the addition of nasr Allah beside the spear on the reverse shows that the legends were not merely slavishly copied from a preceding type, and it seems hard to imagine that such sophisticated thought should have been given to the imagery only for the legends to have been applied so inappropriately. Furthermore, closer examination reveals that the images on both sides of this type are less straightforward then they may first appear. The figure on the obverse, whom Treadwell identified as being the caliph, wears a peculiar type of headgear, has cross-hatching across his breast to represent a different type of dress from the norm, and rather awkwardly carries a sheathed sword. Treadwell notes that the figure on the reverse of the Standing Caliph drachm, like that on the obverse of the gold and copper Standing Caliph types, similarly carries a sheathed sword, and he therefore suggests that this feature identifies the Mihrab and ‘Anaza bust as that of the caliph also. He has no explanation for the design of the crown or helmet, beyond noting that it is does not look like any other crown seen on the coinage of any Sasanian ruler. As for the cross-hatch pattern on the figure’s breast, Treadwell’s explanation is that this is chiefly an artistic rather than a naturalistic feature, designed to allow the sheathed sword to feature more prominently. Unfortunately, neither the cross-hatching nor the headgear looks even remotely like the dress of the Standing Caliph figure and so, much as with the problematic legends, these features do nothing to support to the suggestion that the Mihrab and ‘Anaza drachm was designed to improve and rectify the Standing Caliph type. The object on the reverse, to which Miles devoted most of his attention, has traditionally been identified as a spear or lance within a mihrab. It was Miles who refined this, specifiying that the spear was the ‘anaza of the Prophet himself, and suggesting rather more cautiously that the mihrab could be identified more precisely as the niche type (mihrab mujawwaf). If so, this coin would be the earliest depiction of this important Islamic architectural feature. Miles’ interpretation of the arch as a mihrab has met with a mixed reception among later scholars. Some have endorsed his view that the feature is indeed a Muslim mihrab rather than any other kind of arch, while others (including Treadwell) have pointed out that arches of this type are found on coins struck by all three Abrahamic religions. Connections with the Christian sacrum in Jerusalem (the arch which stood over the True Cross) have been suggested. In this way, this remarkable coin would have played its part in the so-called ‘war of images’ between the Christians and Muslims during this period. It is perhaps worth remembering, however, that the Mihrab and ‘Anaza type is not so securely tied to Damascus during the mid-70s Hijri as some might imply. Treadwell reports that Miles himself ‘did not consider that the coin, as he had described it, fitted smoothly into the series of Damascus silver coinage of the mid-690s.’ The type is not dated, and while the metrology does argue against these drachms having been struck as part of the main series produced in the East, Damascus was not the only place where lighter Arab-Sasanian drachms were being issued at this time. Drachms struck in Armenia and the North (see lot 1) during the 70s seem to have been struck to a weight standard in the region of 3.3g, and like the Mihrab and ‘Anaza type carry on the obverse a bust which is clearly Sasanian but is obviously different from the familiar Khusraw II type which had become the standard in the East for decades. Another curious feature of the Mihrab and ‘Anaza drachms is the large number of dies used: the seven specimens listed by Treadwell were struck from seven obverse and six reverse dies. Is this consistent with a short-lived, experimental type concocted hastily in Damascus and quickly abandoned, or might this be better explained in the context of a short-lived, specific event such as a military campaign?For the full version of this footnote please see the PDF at www.mortonandeden.com/pdfcats/85.pdf

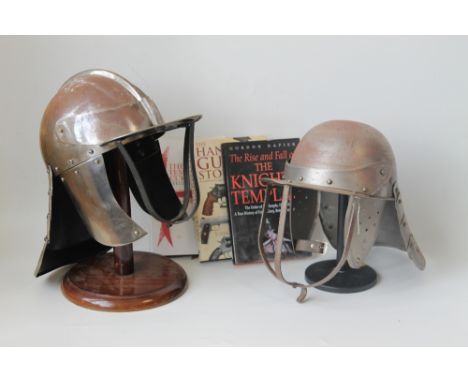

A KHEDIVIAL GUARD'S HELMET, 19th Century, the tall steel skull surmounted by a steel crescent on brass mount, the nasal bar in the form of a downward pointing adjustable arrow with brass fletching and head, brass border, brass ear panels in the form of five pointed stars and brass-bound neck guard, retaining its leather lining and chainmail to the back of the neck guard. 30cm tall from the neck guard to the crescent finial

***PLEASE NOTE DESCRIPTION IN PRINTED CATALOGUE SHOULD READ***AN ANCIENT ORDER OF HIBERNIANS SWORD, early 20th Century. The shagreen and wire handle and helmet shaped pommel form part of the attractive hilt above profusely etched double edged blade, with decorative metal scabbard with figurative mounts.

A BOX CONTAINING A LARGE QUANTITY OF BRITISH MILITARY CAP BADGES HELMET PLATES WWI/WWII ERA AND BEYOND, some possibly re-strikes, great selection of Regiments and Corps are represented here to include, Machine Gun Corp, Line Regiments Yeomanry etc, also included are approximately 25 fastening wires for plates etc, also a small bag with assorted buttons badges etc

AFTER SIR ANTHONY VAN DYCK, portrait of King Charles I (1600-1649), half length, in armour and wearing the lesser George of The Garter, holding a baton and resting his left hand on his helmet, oil on relined canvas, approximately 120cm x 91cm (Provenance: This portrait hung in The Angel Croft Hotel, Lichfield for many years)

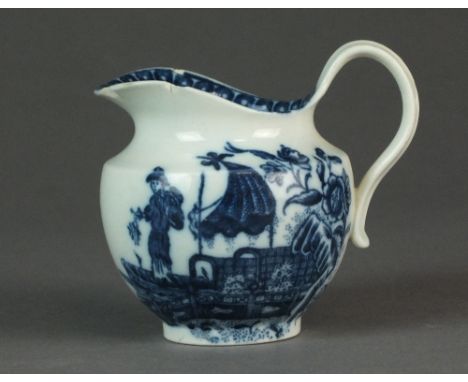

A Caughley helmet form milk jug, circa 1785-94, transfer-printed in underglaze blue with the Fisherman or Pleasure Boat pattern, raised double indented handle with a kick terminal, 8cm high (chipped)Provenance: Wright Collection no.527, purchased in 1997 from Nicholas Gent. Literature: Ironbridge 1999 no.333. A rare shape which is rather like the coal scuttle type jug usually in Pagoda but with a rather small spout and plain handle. Apparently unrecorded, though see collection no.786 for a similar Caughley jug in the Chantilly pattern.

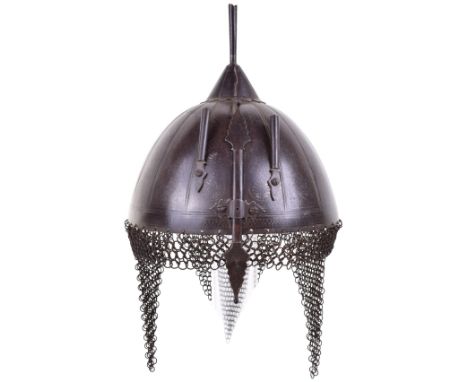

Long Indian Mail Helmet Kulah Zirrah, Probably 17th Century, comprising alternate rows of solid and riveted links, the upper part composed of thick links, the lower part of smaller links, radial iron top plate with tall iron spike. Good condition, lightly rusted overall with a few links missing.

Indian ‘Devil’s Head’ Helmet Kulah Khud, 19th century, iron bowl embossed with a stylised face, and fitted with a pair of horns, nasal bar with pierced finials secured by a moustache-shaped bracket, and leaf-shaped top spike, and fitted with a camail of butted iron links. Good untouched condition, lightly rusted overall.

Good Indian Helmet Kulah Khud, 19th century, bowl raised from a single plate and chiselled overall with flowering foliage and with extensive gold koftgari decoration, border also with some silver koftgari decoration, and fitted with a sliding nasal bar, a pair of plume sockets, a square-section top spike and a camail of butted links. Good untouched condition.

Indian Helmet Kulah Khud, 19th Century, probably Delhi or Sialkot, the bowl of fluted ‘melon’ shape with fine silver koftgari decoration overall (silver requires cleaning), fitted with a pair of plume sockets, top plume socket, and sliding nasal bar, camail of butted links. Good untouched condition and excellent patina.

Rare Ottoman/Turkish Shirvan-Shah or Ak-Koyunlu Iron Turban Helmet, 15th Century or Early 16th Century, embossed with 16 vertical flutes, one piece bowl rising to a typical flared finial above a pierced and facetted device, and fitted with a sliding nasal bar with spade-shaped finial, tall plain border pierced to hold a [missing] camail. Diameter of bowl 24cms. Quite good condition, rusted overall, some forging flaws and a little filling.

Large Heavy Persian Qajar Helmet Kulah Khud, 19th century, iron bowl embossed with a stylised face, and fitted with a pair of horns, ears and plume sockets, together with a nasal bar and square-section top spike, etched overall with eyes, moustache, birds inhabiting foliage, back with 4 seated princes seated in arcades with flasks and fruit etc, the border with cartouches containing inscriptions, retaining some silver damascened decoration overall, camail of iron and brass butted links in decorative patterns. Good condition.

Persian Qajar Helmet Kulah Khud, 19th century, bowl fitted with a sliding nasal bar secured by a thumb screw, a pair of plume sockets, and a square section top spike, the bowl comprehensively etched overall with hunting scenes including numerous mounted figures armed with swords, spears, bows and hawks pursuing lion, antelope, hares and boar, the border with panels containing cartouches filled with inscriptions, retaining some silver damascened decoration overall, and fitted with a camail of butted iron links. Good condition.

Late 16th Century Heavy Italian Helmet Cabaset, raised from a single plate, tall peak with ‘pear stalk’ finial, distinct medial ridge, border pierced for [missing] brass rosettes, integral brim with turned over edge slightly pointed at front and back, smooth polished exterior finish. Good condition.

-

70379 item(s)/page