We found 62920 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 62920 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

62920 item(s)/page

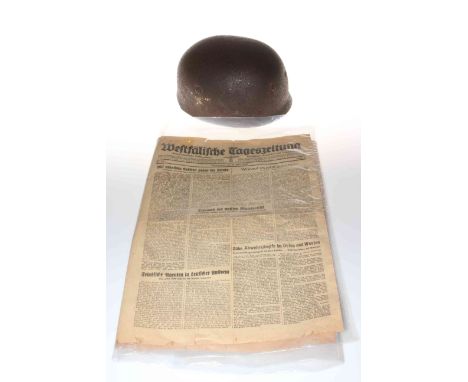

11th-12th century AD. A four-plate iron helmet constructed from curved triangular sections with a slight point at the apex; the bowl contoured so that the front and back plates overlap the side-plates by 1-2cm, with iron rivets passing through this overlap to secure them in position; the rivets worked flat into the surface of the helmet, almost invisible from the outside but detectable on the inner surface; the plate-junction at the apex supplied with a small loop, allowing a plume or horsehair streamer to be inserted; mounted on a custom-made stand. See Curtis, H. M., 2,500 Years of European Helmets, North Hollywood, 1978; Denny, N. & Filmer-Sankey, J., The Bayeux Tapestry, London, 1966; Kirpicnikow, A. N., Russische Helme aus dem Frühen Mittelalter Waffen- und Kostamkunde, 3rd Series, Vol. 15, pt. 2, 1973; Menghin, W. The Merovingian Period - Europe Without Borders, Berlin, 2007, p.326-7, item I.34.4. 1.2 kg total, 32.5cm with stand (12 3/4"). From a North West London collection; previously acquired in the 1980s. Helmets of this general profile and with some form of conical crest are a long-lived military fashion in the Black Sea region, and appear in designs on the bone facing of a Khazar saddle of 7th-8th century date from the Shilovskiy gravefield (Samara region); a similar helmet (of presumed 5th century AD date) is housed in the St. Petersburg Museum (inventory reference PA72), previously in the MVF Berlin until 1945 under inventory ref.IIId 1789i. The rivetted-plate construction was employed across Europe from the Migration Period through to the 12th century: it is this form which appears on the heads of English and Norman warriors in the Bayeux tapestry. Fine condition, some restoration.

5th century AD. A silver-gilt bow brooch comprising a triangular headplate with cabochon amethyst(?) to each angle, deep ribbed bow, footplate formed as a beast-head with pellet eyes and teeth visible at each side, recurved catch to the reverse. Cf. Tejral, J. Morava na Sklonku Antiky, Prague, 1982, item 93(2"). 27.6 grams, 75mm (3"). Property of a gentleman; acquired in the late 1960s-early 1970s. The footplate is an almost exact copy of the beast-head on the face-plate of the Sutton Hoo helmet. Fine condition.

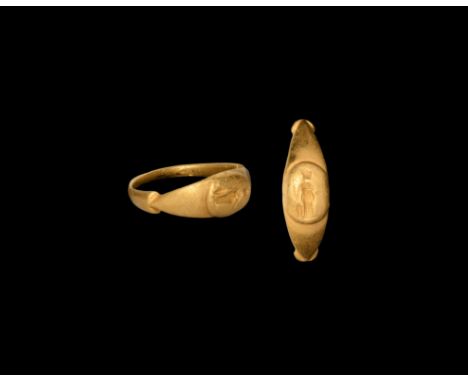

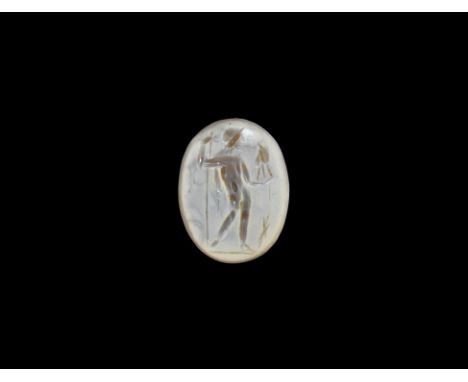

1st-2nd century AD. A gold finger ring with stepped shoulders, ellipsoid domed bezel with intaglio Minerva standing with helmet, spear and shield. 6.52 grams, 23.16mm overall, 18.51mm internal diameter (approximate size British P, USA 7 1/2, Europe 16.23, Japan 15) (1"). Property of a private collector; acquired before 1975. Fine condition.

2nd-3rd century AD. Two sheet silver embossed plaques for a pseudo-Attic helmet, each with shaped edges, embossed around the edges with a double-pearled ornament, with fixing holes; the decoration of both plaques seems to represent a cult scene, most probably to Jupiter and Epona, in one plaque, to Jupiter alone; the bust of Jupiter is represented on both plaques at the centre of the diadem, frontally, with long, symmetrical hairstyle; he is dressed in a simple folded tunic; an eagle at his right side, his favoured bird and symbol of his power over the skies, as well as of the eternal power of Rome; the feet of both eagles rest on thunderbolts, composed from a turtled elongated body; to the first plaque, another divinity is represented to the left of Jupiter, most probably Epona, left hand holding a staff surmounted by flowers, fruit and ears of corn (cornucopia?); on the left side of the plaque, under the divinities, are two advancing cavalrymen, one dressed with a padded tunic of Celto-Danubian typology, holding a short sword, the other unarmed and lightly dressed; opposite, the god Silvanus seated and covered only by his mantle, is offering the victory laurel to an eagle resting over a basket, caressing a dog; and three female figures (one half naked and with the breast exposed, the other two dressed with chiton and chlamys) are performing an offering in front of a templar construction, one figure holding a staff and the other a standard ending with a seven-pointed star; at the feet of the woman with the staff another dog is lying, probably again associated with the offering god; to the second plaque: the embossed decoration consists mainly of an armed cavalryman, identical to that one on the previous plaques, advancing towards Zeus/Jupiter; two different cult scenes are represented on the sides, on the left a divinity (maybe Silvanus), leaned upon a staff, is offering gifts to a divinity (Epona?), represented as a bust; on the right side a similar figure offering gifts to a cavalryman, preserved only in his lower part; under the central figures are again represented, in smaller dimensions, two divinities, Zeus/Jupiter and Athena/Minerva, the one holding a staff, the second one helmetted and carrying a spear with her right hand, the other hand on a shield; the two figures are flanked by a naked horseman, while the heads of the twins Castor and Pollux are positioned on both their flanks; both plaques with holes for the fastening through small rivets on their sides (still present in the smaller plaques, only one preserved in the bigger plaque), intended to affix the plaques to the crown of the helmet; mounted on perspex.See Fray Bober P., Reviewing Réne Magnen, Epona, Déesse Gauloise des Chevaux, Protectrice des Cavaliers, in American Journal of Archaeology, 62.3, July 1958, pp.349-350; Robinson, R., The Armour of Imperial Rome, New York, 1975; D'Amato, R., Arms and Armour of the Imperial Roman Soldier, London, 2009; Negin A. Roman helmets with a browband shaped as a vertical fronton, in Historia i ?wiat, 2015, 4, 31-46; D'Amato R., A. Negin, Decorated Roman Armour, London, 2017; the helmet browband embossing has parallels with other splendid vertical fronton-shaped specimens, like the helmet from PamukMogila, the fragment of helmet from Leidscherijn, the browband from Leiden, and the very famous helmet recently found in Hallaton (D'Amato-Negin, 2017, fig.62 c, p.64-66); the piece preserved in the National Museum of Antiquities (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden) in Leiden (D'Amato-Negin, 2017, fig.65) shows similar embossing and side holes for fastening. These embossed plaques would have been affixed to the browbands, of the ‘pseudo-Attic’ helmets of the Roman army. The existence of these helmets, the most represented in Roman art (Robinson, 1975, p.182, pl.494; pp.184-185, pls.497-499, 501) although less documented in archaeology, have been a matter of controversy amongst scholars. 1.02 kg total, 30-35cm long (11 3/4 - 13 3/4").Ex an important Dutch collection; acquired in the European market in the 1970s; accompanied by an expertise by military archaeologist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.Despite a number of experts doubting their existence, Russell Robinson published the brow-band of a surviving example over forty years ago (1975, pp.138-139, pls.417-220"). Some scholars are absolutely confident of their existence (D'Amato, 2009, pp.112-114; 206ff.), while others considered the many images of Attic helmets on Roman monuments simply an artistic convention. Recently, Andrei Neginhas collected a good series of samples showing that the presence of these helmets was a reality of the Roman Army (Negin, 2015), a thesis further reinforced in D'Amato and Negin’s 2017 work on Roman decorated armour. Both the authors have shown full evidence with finds suggesting that Attic helmets with browbands, which are often depicted in Roman public art, are no mere convention, but were actually common in the Roman imperial army, imitating models from the earlier period. In the case of similar helmets worn by the Praetorians, it can be assumed that they had more archaic shapes, imitating Greek models. They are exceptionally rare pieces, coming with all probability from a military camp on the Danube. The scene represented here shows a cult to divinities popular among the legions of the Danube; the presence of cavalrymen recalls the cult of the Danubian rider gods, here dressed like a Thracian auxiliary cavalryman of the Roman army, and joined by the rider gods par excellence, the twins Castor and Pollux. The presence of Epona, protector of horses, goddess of fertility, confirms the helmet’s Danubian origin, Epona being 'the sole Celtic divinity ultimately worshipped in Rome itself' (Fray Bober, 1958, p.349"). Her worship as the patroness of cavalry was widespread in the Empire between the first and third centuries AD; this is unusual for a Celtic deity, most of whom were associated with specific localities. Here, she is associated with Silvanus, a god also venerated in the Danubian provinces, a divinity especially popular in Pannonia, and in the cities of Carnuntum and Aquincumwhere he was worshipped as Silvanus Orientalis, the divine guard of the borders.[2] Fragmentary.

7th-6th century BC. An exceptionally well preserved bronze combat helmet of Archaic Corinthian type, with high bowl made from two separate metal sheets with a protruding neck protection; large eye openings, and arched enveloping cheek pieces; with a long, rivetted, slightly outward projecting nose protection; around the edges of the eyebrows and nose-guard are regularly spaced holes with decorative round-headed rivets for the attachment of the inner padding; an ancient repair hole visible over the left eyebrow; trace of a battle blow on the back of the skull; mounted on a custom-made display stand. See Holloway, R.R., Satrianum; the archaeological investigations conducted by Brown University in 1966 and 1967, Brown University Press, 1970; Bottini, A., Egg. M., Von Hase F. W., Pflug H., Schaaf U., Schauer P., Waurick G.,Antike Helme, Sammlung Lipperheide und andere Bestände des Antikenmuseums Berlin, Mainz, 1988; Museo Nazionale del Melfese, Nuovi rinvenimenti nell’area del Melfese. Soprintendenza Archeologica della Basilicata, Melfi, 1996; D’Amato R., Salimbeti A., Bronze Age Greek Warrior, 1600-1100 BC, Oxford, 2011; D’Amato R., Salimbeti A., Early Iron Age Greek Warrior, 1100-700 BC, Oxford, 2016; similar helmets from Torre di Satriano e Benevento (Bottini, Egg, Von Hase, Pflug, Schaaf, Schauer, Waurick, 1988, p.72, fig.7, cat.14 p.392) and Melfi (Museo Nazionale del Melfese, 1996, p.4"). 870 grams, height 22.5cm (8 3/4"). From a private English collection in 2001; acquired from Frank Sternberg, Zurich, Germany in 1993; previously in a 1980s Israeli collection; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato; a copy of the 2001 invoice and an Art Loss Register certificate no. S00156427.Widespread in the seventh and sixth century BC, the Corinthian helmet provided maximum protection with its nasal and its broad cheek plates. Herodotus mentions the Corinthian helmet in his Histories (4.180) when writing of the Machlyes and Auseans, two tribes living along the River Triton in ancient Libya. The tribes chose annually two teams of the fairest maidens who fought each other ceremonially with sticks and stones. They were dressed in the finest Greek panoply topped off with a Corinthian helmet. The ritual fight was part of a festival honoring the virgin goddess Athena. Young women who succumbed to their wounds during the ordeal were thought to have been punished by the goddess for lying about their virginity. The Corinthian helmet was the most popular during the Archaic and early Classical periods, with the style gradually giving way to the more open Thracian helmet, Chalcidian helmet and the much simpler pilos type, which was less expensive to manufacture and did not obstruct the wearer's critical senses of vision and hearing as the Corinthian helmet did. Numerous examples of Corinthian helmets have been excavated, and they are frequently depicted on pottery. The Corinthian helmet was depicted on more sculpture than any other helmet; it seems the Greeks romantically associated it with glory and the past. The Romans also revered it, from copies of Greek originals to sculpture of their own. Based on the sparse pictorial evidence of the republican Roman army, in Italy the Corinthian helmet evolved into a jockey-cap style helmet called the Italo-Corinthian, Etrusco-Corinthian or Apulo-Corinthian helmet, with the characteristic nose guard and eye slits becoming mere decorations on its face. Given many Roman appropriations of ancient Greek ideas, this change was probably inspired by the 'over-the-forehead' position common in Greek art. This helmet remained in use well into the 1st century AD. Excellent condition, complete. An extremely rare early type.

Mid 14th century AD. A German great helm of later type with the lower part missing, but still visible in its original shape; comprising five plates rivetted together: one plate forming the top, rivetted by fifteen iron studs; two forming the front part, the top occipital plate also rivetted by fifteen iron studs, nine of which are the same rivetted to the top; the lower facial plate still fastened with eight studs, two of them attaching a T-shaped nose-guard raising on the upper plate; the back upper plate fastened by twenty-four rivets, the lower nine ones also rivetting the lower plate; eight holes (two in the upper frontal plate, six in the upper back plate) are visible and were intended for the fixing of the internal padding system; the top of the helmet is convex; the visual system is divided into two parts, and on both left and right parts with remaining holes forming the ventilation system. See Boeheim W.,Handbuch der Waffenkunde. Das Waffenwesen in seiner historischen Entwickelung vom Beginn des Mittelalters bis zum Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts, Leipzig, 1890; Pierzak J. ?redniowieczne he?my garnczkowe na ziemiach polskich na tle zachodnioeuropejskim, Bytom, 2005; Wild W., Unter schrecklichem Knallen barsten die Mauern – Auf die Suche nach archäologischen Spuren von Erdbebenkatastrophen, in Mittelalter, 11, 2006, pp.145-164; Lüken S., Topfhelm, in Aufbruch in die Gotik. Der Magdeburger Dom und die späte Stauferzeit. Band II. Katalog, ed. Puhle, M. Lammert, N., Magdeburg-Mainz, 2009, p.376; Lüken S., Topfhelm, inBurg und Herrschaft, ed. Atzbach R., Lüken S., Ottomeyer H., Berlin-Dresden, 2010, p.74; Žákovský P., Hošek J., Cisár V., A unique finding of a great helm from the Dale?ín castle in Moravia, in Acta Militaria Mediaevalia, VIII, 2011, pp.91-125; the structure of the helm shows similarity with the helmets of Dargen (Žákovský, Hošek, Cisár, 2011, fig.9a) found at the Dargen Castle near Deerberg and kept today in the collections of the Berlin Zeughaus, dating back to the second half of the 13th century (Lüken, 2009, 376, cat. no.VI.13; 2010, 74, cat. no.3.11); with the helmet of Madeln Castle (Žákovský, Hošek,Cisár, 2011, fig.9a) found during the research in 1940, nowadays stored in the collections of the Liestal Museum, dated to the end of the 13th century, with a possible overlap into the turn of the following century, although the helm was probably buried during the devastating earthquake in 1356 AD during which Madeln Castle was destroyed (Wild, 2006, pp.146-147); and other helmets like the ones of Küssnach Castle, Bolzano and Tannenberg (Žákovský, Hošek, Cisár, 2011, figs.9c-9d-9e), dated, respectively at the second quarter of the 14th century, early 14th century and 1350 AD. This item also has parallels with the recently published five plate helmet from Dale?ín castle dated to 1340 AD (Žákovský, Hošek, Cisár, 2011, p.114"). 1.7 kg, 27cm (10 1/2").From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.This helm belongs to the category of the Great Helms made of five separate plates rivetted together. The chronological indicator for the Great Helms with five plates, suggested by Žákovský, Hošek, Cisár (2011, p.100), is the shape of the top occipital plate. This plate, flat in older helmets dated to 13th and early 14th century, is convex to hemispherical in the helmets made between 1320 and 1330 AD, followed by a conspicuous rib following the longitudinal axis of the plate. This is the case of the Dale?ín helmet and also of our specimen. The modification of the top occipital plate from flat to convex or hemispherical was better suited to deflecting potential blows of the opponent away, or perhaps responded to the fact that, since the beginning of the 14th century, lighter helmets were worn under the Great Helms to provide the wearer with more comfort, a generally better view and more peripheral vision.Fair condition. Extremely rare.

19th century AD. A substantial bronze Zhou style helmet from a statue(?) domed with raised panels to the brim and vertical crest, hollow-formed spike above; the face-opening with shallow peak to the upper edge. 3.1 kg, 36cm (14 1/4"). From the property of a London gentleman; formerly in a UK collection, acquired in the 1990s. [No Reserve] Fine condition.

2nd century AD. A copper-alloy tinned fibula representing a gladiator of the secutor class, armed with a short dagger (sica), protected by a helmet (galea), and a curved rectangular shield (scutum), on the leg some stylisation of greaves (ocreae"). For similar fibula see Gorny & Mosch Auktionskatalog, 235 Kunst der Antike, am 16. Dezember 2015 in München bei Gorny & Mosch Giessener Münzhandlung GmbH am Maximiliansplatz, published on Nov 5, 2015, p.168, n. 342. 13.8 grams, 42mm (1 1/2"). Property of a private collector; acquired before 1975. The rounded helmet, with a smooth bowl and a crest (galea) prevented the secutor’s main adversary, the retiarius, from harming the secutor with his net. This helmet was generally made from iron or bronze, was very heavy and inside it had leather or wool padding to make the wearing more comfortable; a visor with small holes limited vision but protected the eyes. An imposing and concave shield (scutum) protected the combatant from the knee to the face, leaving the visor barely exposed; the upper part of the shield was rounded, without grips,also to protect the combatant from the retiarius’ net. The shins were exposed, protected by a metal greave over a wool bandage which also provided cushioning against blows. A sleeve usually made up of metal or leather scales / plates, which slightly limited movement , was placed on the gladiator's right arm, helping him to avoid injuries to the exposed arm. The secutor was armed with a small and manageable sword. Very fine condition.

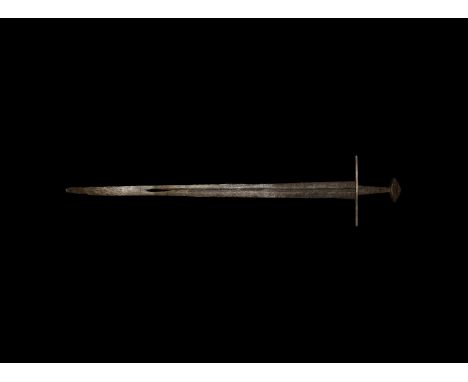

Mid 10th-mid 11th century AD. An elegant, finely tapering blade with well-formed fullers, running down to within 23cm of the point, the cutting edges in good condition bearing much evidence of use, long (almost 20cm) narrow cross of the type known by the Vikings as gaddhjnlf or spike-hilt, stout tang, tapering and terminating with a beautifully preserved walnut style pommel. See a parallel sword in Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002, p.131 (Paris, Musée de l'Armée, inventory JPO 2241); D'Amato R., Spasi? Duri? D., The Phrygian helmet in Byzantium: archaeology and iconography in the light of the recent finds from Branicevo, in Acta Militaria Mediaevalia, tom XIV, 2018, pp.29-68. 742 grams, 95cm (37 1/2").From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent.This one-handed sword shows the same walnut pommel of the swords visible on the lost miniatures of the Hortus Deliciarum (D'Amato-Spasi? Duri?, 2018, p.53), a German manuscript of the second quarter of 12th century. The straight guard with thick straight quillons are typical of the style Xa of Oakeshott, a kind of sword that, with its double-edged blade, combined the cutting and the cut-and-thrust styles. The fullers, like in this case, are very marked and form not less than two thirds of the length.Fair condition.

13th-14th century AD. A gilt bronze figure modelled in the half-round, standing wearing a knee-length robe and high boots, conical helmet(?) and coif, arms bent across the chest; hollow to the reverse with fixing hole at knee height. 34.9 grams, 76mm (3"). From the family collection of a Hampstead gentleman; formerly acquired in the 1980s. Fine condition.

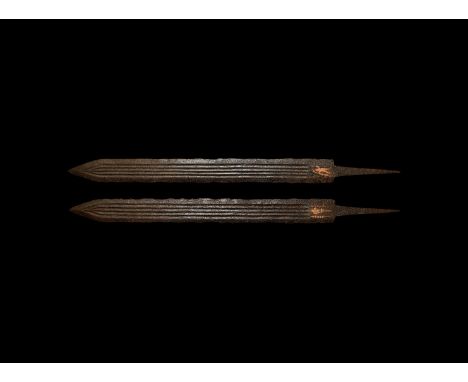

Early 3rd century AD. A double-edged longsword (spatha) of Lauriacum Hromówka typology; well preserved blade, with four blood channels running three quarters of its length, wider and parallel cutting edges tapering towards the triangular point; inlaid decoration at the height of the sword’s shoulders, showing on one side the figure of Mars Ultor, standing in armour (statos), shield (aspis) and plumed helmet (galea), holding a spear with the left arm, on the other side the aquila of the Legion flanked by two military standards (signa), fitted with four phalerae and with at the top a wide hasta pura. See Biborski, M.,‘Miecze z okresu wp?ywów rzymskich na obszarze kultury przeworskiej’, in Materia?y Archeologiczne XVIII, 1978, pp.53-165; Robinson, H.R., What the soldiers wore on Hadrian’s Wall New Castle on Tyne, 1976-1979; Czarnecka, K.,‘Two newly-found Roman swords from the Przeworsk culture cemetery in Oblin, Siedlce District, Poland’ in JRMES 3,1992, pp.41-56; Bishop, M. C. – Coulston, J.C.N., Roman military equipment, from the Punic wars to the fall of Rome, London, 1993; Biborski, M. ‘Römische Schwerter im Gebiet des europäischen Barbaricum’, in JRMES 5, 1994, pp.169-198; Southern, P., Dixon, K.R., The Late Roman Army, London, 1996; Dautova Ruševljan V., Vujovi?, M.,Roman Army in Srem, Novi Sad, 2006; Biborki, M./Ilkjar J., Illerup Ådal 12. Die Schwerter. 1. Textband. 2. Tafeln und Fundlisten, Moesgard, 2006; Miks, C., Studien zur Romischen Schwertbewaffnung in der Kaiserzeit, I-II Banden, Rahden, 2007; Cascarino, G.,Sansilvestri, C.,L’esercito romano, armamento ed organizzazione, vol.III, dal III secolo alla fine dell’Impero d’Occidente, Rimini, 2009; Radjush, O.,‘New armament finds of the Scythian wars' epoch in the northern Black Sea region’ in Busch, A. W. and Schalles, H.-J. (eds.), Waffen in Aktion. Akten des 16. Internationalen Roman Military Equipment Conference (ROMEC), Xanten, 13.-16. Juni 2007, Xantener Berichte 16, Darmstad, 2009, pp.183-8; Guillaud I., Militaria à Lugdunum: étude de l’armement et de l’équipement militaire d’époque romaine à Lyon (1er s. av.-IVe s. apr. J.-C.), Archéologie et Préhistoire, Lyon, 2017; D’Amato, R., Roman army Units in the Western Provinces, Oxford, 2019; for very similar specimens see Miks, 2007, n.A146,3; A146,10 (Ejsbol); A384 (Krasnik-Piasti); A595 (Pontoux); A830 (Sisak); A620 (Rezeczyca Dluga); A586 (Pododlow); A676 (Sobotka); A211 (Kielce"). 832 grams, 74cm, 6cm wide (29").From a Cambridgeshire private collection since 2008; formerly in a Nottinghamshire collection since the 1980s, accompanied by an expertise from the military specialist Dr. Raffaele D’Amato.Although in Latin literature the late Roman sword was often still conventionally called gladius (Ammianus Marcellinus, Historiae, XIX, 6; Passio SS. Rogatiani et Donatiani,1859, p.323), the main kind of blade of the Roman third and fourth century soldier belongs to the so-called spatha type (Scriptores Historia Augusta, Divus Claudius, XXV, 7, 5; 8, 5) which derived directly from the long cutting Celtic sword of the La Tène III period, already used by the cavalrymen and Auxilia of the previous Ages. The great spatha (spathì) of the Roman heavy infantryman was considered by Julius Africanus (Fragm., I, 1, 53) as the main weapon of the armoured legionary of Alexander Severus. The frequent clashes with Germanic warriors armed with long swords and the increased recruitment by the Roman army lead to the growth of spatha use by the milites legionarii (DautovaRuševljan-Vujovi?, 2006, p.50"). These longer swords slowly replaced the shorter gladius, the double-edged sword of the imperial infantry, for all troops. Vegetius (Epitome de re military, II,15) calls the spatha a gladius maior, i.e. a great sword, sometimes a metre long. A wide range of spathae have been found dating from the late second to the late fourth century AD (D’Amato, 2019, p.14"). There are today several hundred attested Roman longswords scattered throughout Europe. Specimens of Roman spathae of the second and third centuries have been found in large numbers in the Danish bogs (Nydam, Straubing, Thorsberg, Illerup"). These swords show a great deal of variability, in terms of shape and dimensions; today a typological framework is well-established, thanks to the work of academics including Ulbert, Biborski and Miks. This particular type is the Lauriacum-Hromówka of which more than 30 specimens have been found in Poland.Fine condition. Scarce.

16th-17th century AD. A war hammer or Nazdiak of Polish origin, the head composed of two pieces; the twisted shaft made of solid iron, and the head, made of one single piece, shaped like a hammer from one side and a pointed spike or dagger from the other side; the dagger showing a strong quadrangular outline, fixed to the shaft with an upper insertion hole and then rivetted, with the help of an auxiliary iron cap; its spike of a 'raven beak' shape of quadrangular section, while the hammer is flat at the top; the shaft is particularly twisted, and ends, in the lower part, with a short handle. See Йотов В, Въоръжението и снаряжението от българското средновековие (VII-XI век), Варна, 2004; Brzezinski, R., Polish Armies 1569-1696 (1), London, 1987; Gilliot, C., Armes & Armures/Weapons & Armours, Bayeux, 2008. 2.1 kg, 60cm (23 1/2").From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.The war hammer was a bulky weapon. The wider use of hammers, especially among riders, began in the 13th century, with the spread of armour, although traces of war hammers could already be found in 10th century Byzantium, with the weapon called akouphion (Yotov, 2004, pp.106-107"). At the beginning it was made of a lead cylinder, extremely heavy with a handle (Gilliot, 2008, p.150"). In the late Middle Ages (XIV-XVI centuries), with the introduction of a new means of defence - the plate armour, against which swords, axes, maces and other melee weapons were less effective, various types of war hammers became widely used. The old cylindrical plommée (lead cylindrical hammer) were replaced in the early 15th century, by the more solid and light iron hammer. This was a lighter weapon, not exceeding 2.5 kg, the knob of which was a hammer itself or had a hammer on one side and a beak on the other, that is, a facetted spike or a massive blade of different lengths, a straight or slightly curved blade. The name hammer comes from one of the elements of the warhead, even if the a real hammer itself may not be on it. Because of their appearance, hammerheads with beaks were often known by bird-related names, such as ‘black beak’ in Spain, ‘crow’s beak’ or ‘eagle’s beak’ in France, ‘falcon beak’ in Italy and ‘parrot beak’ in Germany and Poland. The bec de courbin' had a particular pointy beak aimed at delivering strong thrusts. Often there was also a point pointing upwards and additional short spikes, directly inserted on the impact surface of the hammer or sideways. The beak was capable of breaking chain mail or breaking through plate armour. With a hammer, the enemy could be stunned and his armour deformed. Beaks could also be used to capture the enemy, primarily pulling the rider off of his horse. But for this, hammers having long shafts were better suited. In this case the bec de courbin took up a long handle in the middle 15th century and was called, because of its primary use by the Swiss infantry, 'Lucerne Hammer'. Compared to the mace and the axe attached to the saddlebow (arcione), the war hammer originated several variants which, to date, make it rather difficult to discriminate its archetypal form. The weapon presented here had in fact, enormous similarities with the horseman's pick, only in some of its regional variants well distinguishable from the war hammer (eg. the Polish nazdiak,) often called a raven-headed hammer of the type here represented. It has good parallels with Polish originals of 16th-17th centuries in the Wojska Polskiego Museum (Polish Army Museum), Warsaw, and illustrated in contemporary documents (Brzezinski, 1987, p.41"). Most probably this specimen is from a battlefield or a castle as it is in excellent condition. The horseman's pick has remarkable similarities with the war hammer, so that some variants of the two weapons are almost identical. In the Germanic areas, both weapons are identified as hammer ('hammer' in German language): reiterhammer ('knight's hammer') the horseman's pick and kriegshammer ('war hammer') the war hammer. The distinguishing element is the shape of the hammer head. Weapon apt to injure by blow, the proper war hammer had often a serrated and massive head. The hybrid forms (eg. Polish czekan,) similar to the peak of arms, instead present a hammerhead reduced to a mere counterweight for the long metallic 'beak' that protrudes on the other side of the head, destined to pierce the armor or the opponent's helmet. However, by comparing a Polish nazdiak with a French or Italian war hammer, fundamental differences stand out. There where the western war hammer (like the heaviest Italian mazzaapicchio) which is able to strike both with the head of the hammer, often toothed, and with the curved tip; the horseman's pick striking mainly with the pointed peak, while the hammerhead was reduced to a mere counterweight. Another distinctive feature of the Polish nazdiak is it being made entirely of metal, like the Italian war mace, and it being longer than the war hammer. Eloquent in regard to its efficiency, is the witness of the account of Abbot J?drzej Kitowicz, who lived at the time of August III of Poland (1696-1763): '[The nazdiak] is a terrible instrument in the hands of the Poles, especially if they are in a warrior or altered mood. With the sabres you can cut off someone's hand, tear his face and injure him in the head and the sight of the blood that flows from the enemy can thus calm the resentment. But with the nazdiak you could cause a fatal injury without seeing the blood and, not seeing its, calm down, instead ending up hitting several times without cutting the skin but breaking bones and vertebrae. The nobles with clubs often beat their servants to death. Because of the danger it posed, they were forbidden to be armed during large assemblies or parliamentary sessions. [...] And in truth, it was a brigand's instrument, because if you hit someone with the pointed beak of the nadziak behind the ear, you kill it instantly, the temple pierced by the deadly iron. '(Jędrzej Kitowicz, Opis obyczajów za panowania Augusta III)'.Fine condition. Very rare.

11th-12th century AD. A Western European iron conical helmet of Norman or German origin, with one-piece bowl, the fairly low central ridge tapering off at the forehead to which a nose-guard was originally attached; the back of the neck around the lower edge is still preserved; on the front part of the helmet where the rim is completely preserved, eight holes of the original sixteen are visible, intended to fix the internal lining. See Gravett, C., Norman Knight, 950-1204 AD, London,1993; Hermann Historica, 58 Auktion, Ausgewählte Sammlungsstücke – Alte Waffen, Militärisches und Historisches Oktober, 2009, München, 2009; Profantová N., Karolinské importy a jejich napodobování v ?echách, p?ípadn? na Morav? (konec 8. – 10. století), in Zborník Slovenského Národného Múzea –archeológia supplementum 4, 2011, pp.71-104; D’Amato, R., Old and new evidence on the East Roman Helmets from the 9th to 12th centuries, in Acta Militaria Mediaevalia XI, Kraków – Sanok – Wroc?aw, 2015, pp.27-157; Coppola, G., Battaglie Normanne di terra e di mare, Napoli, 2015; our specimen has a clear parallel with a helmet presented by Hermann Historica in the auction of 08.10.2009 (Hermann Historica, 2009, cat.488), to which it is completely identical in the upper part, although the European specimen of Hermann Historica was complete with nose-guard; comparable elements are known in German private collections (D’Amato, 2015, p.70, figs.31.1-2); the iconography is rich, a helmet of this type being represented in the Add. Ms.14789, f.10 of the British Library, showing the duel between David and Goliath (Gravett, 1993, p.51"). 716 grams, 21cm (8 1/4").From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.This specimen belongs to the category of helmets beaten out of a single piece of metal. The nasal, as it was probably in this case, could be forged in one with the helmet, although illustrations suggest that many were made with an applied brow-band. Helmets might have been painted, and all helmets were lined. As no lining and few helmets survive, some scholars consider this idea a simple hypothesis based on the presence of rivets and the examples of later helmets. It may be that a band of leather was rivetted inside the brim, to which a coarse cloth lining was stitched, probably stuffed, quilted and possibly cut into the bowl, then adjusted for height and comfort. The helmet would have been supplied with a thong at each side which fastened under the chin to secure it on the head (Gravett, 1993, p.11"). Contemporary references to lacing helmets are common. It also helped to prevent them from being knocked over the eyes. The helmet (cassis) was usually carried fastened under the chin and the presence of a padding inside to cushion the blows was absolute necessary, since a blow of a sword or a mace, even if it did not break through the skull causing immediate death, stunned the knight making him helpless.Fair condition, some loss and surface pitting, restored. Rare.

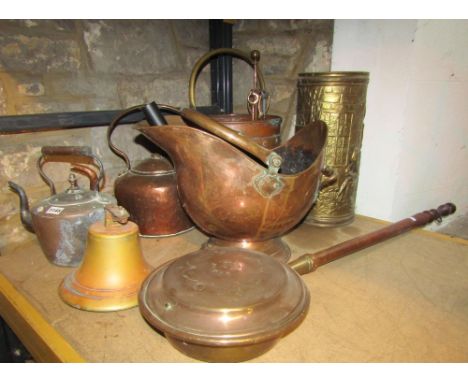

One lot of mainly copper and brassware to include a 19th century copper, helmet shaped coal scuttle, two copper kettles, cylindrical coal bucket, with pop riveted bands, copper bed warming pan, brass bell, together with two floor standing iron work planters and a standard lamp with simple scroll detail (11)

A collection of ceramics including a Wedgwood Fallow Deer pattern helmet shaped blue and white printed jug, further blue and white printed wares, including a Copeland Spode Italian pattern jug, a sauce tureen, cover and stand, etc, together with a collection of Lawleys Art Deco tea wares, Villeroy & Boch dinner and tea wares with white glazed finish, including six dinner plates, six soup or dessert bowls, etc (a collection)

-

62920 item(s)/page