We found 80915 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 80915 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

80915 item(s)/page

A Movado Chronometre Ermeto electroplated slide wind purse watch, c. 1930's, numbered 1240, 687M, with Arabic numerals, working when catalogued, together with six other manual wind miniature travel/bedside clocks, sliding or hinged openings, makers to include Pontifa, Basis, Laco and others together with a French traveling clock with case.

§ George Kennethson (British 1910-1994) Wave Form, circa 1950s-60s Clipsham stoneDimensions:43cm high, 30.5cm wide, 20cm deep (17in high, 12in wide, 7 3/4in deep)Provenance:ProvenanceThe Estate of the Artist.Note: LiteratureCork, Richard. The Sculpture of George Kennethson, Redfern Gallery, London, 2014, p. 20 illustrated in the background of a photograph of the artist's studio. George Kennethson (or Arthur Mackenzie as he was, Kennethson being the name he adopted in the early 1970s in order to separate his artistic practice from his role as the art master at Oundle School) met Eileen Guthrie in 1931 at the Royal Academy Schools in London. Intriguingly both were painting students, although in George’s case, the teaching at the still very academic Academy mainly had the effect of turning him into a sculptor, something he was already considering by his final year when the pair of them met [although one of his sons recalls Kennethson generously saying that the reason he became a sculptor was that Eileen was by far the better painter].George had come from a cultured, literary family. Eileen’s father and grandfather were architects and her mother was an accomplished pianist, who had studied at the Royal College of Music [Eileen herself had been taught piano by Gustav Holst when she was young]. And so, like many of their circle, Eileen and George were left-wing in their politics, interested in all things avant-garde in art, music and literature, and looked to Paris for inspiration. As young artists they both revered Cezanne. On their first trip together to the French capital, George tracked down the work of sculptors Maillol, Zadkine and Brancusi. And Eileen no doubt sought out the work of Bonnard, whose influence, both in composition and technique, can be traced in her work. They returned, in 1937, where they saw Picasso’s recently completed Guernica, which moved them both, artistically and politically. Like many artists of their generation, their lives and careers were profoundly affected by the Second World War. The Kennethsons were committed pacifists. A year before war broke out, they had moved to the quiet Berkshire village of Uffington, watched over by its ancient, curiously abstract White Horse, cut into the chalk of the nearby Downs, and so in away had already withdrawn from the political storm of the late 30s. The local villagers had no issues with the Kennethsons’ avowed pacifism: they were artists, after all, so they expected them to be different. Whilst they passed the war in rural seclusion, conflict does seep into Kennethson’s sculpture, such as sculptures of travellers, with staffs and backpacks, or men carrying mattresses down to the local forge – images glimpsed out of the studio window, but now transformed into a moving response to the refugees that war inevitably creates. The couple took in both evacuees from the Blitz and the occasional European refugee (and much later in the 1980s, Kennethson returned to this theme as a response to the migrations forced by famine in Ethiopia). But more than this, the War and its aftermath led to little opportunity for artists to sell their work and therefore live by their art – something that was particularly acute for the Kennethsons, who by the late 1940s had five young boys to feed. Art historians have often been critical of British artists ‘retreating’ into teaching or commercial work, whilst their counterparts in America were splashing newly made paint across acres of pristine canvas and changing the direction of modern art forever, and yet this ignores the pressures on British artists, facing a public that was already relatively indifferent to modern art already and which now was broke.It was at this point that Eileen turned her hand to making prints for textiles. She did so with incredible success – artistically at least, as there was almost as little money for interiors and design in post-war Britain as there was for at. Eileen did, however, sell her ‘Flockhart Fabrics’ range – named after her Scottish grandfather - at Primavera, a leading interiors shop on Sloane Street, as well as to family and friends. Their neighbour in Uffington, John Betjeman, also helped them to find stockists, and Eileen’s twin sister Joan would open her London flat to showcase the designs. Lucienne Day, too, introduced Eileen to Amersham Prints, contractors to the government, and her design Bird and Basket was used in 1954 to furnish the Morag Mhor, the first all-aluminium yacht in the country.George lent a hand too, on the production side, contributing to designs, working on the lino-blocks and silkscreens and helping Eileen with the considerable manual work of printing the fabrics by hand. The prints are deceptively simple, strong and sculptural, whilst retaining the required elegance and beauty. The line that one sees in her gouaches and oils find an easy home amongst the repeats of fabric design and motifs that infuse George’s sculpture – birds, leaves, architectonic flower forms – are abstracted from her landscape painting.The family moved to Oundle in 1954, to a house with a large former malting attached, which made for good, if draughty, studios. George would have been surrounded by Eileen’s fabrics – at the long settle by the kitchen table or on one of the armchairs where he would read and draw- before heading out to his studio to carve equally simple forms, with soft curves and sharp edges, into stone and alabaster, so perhaps Eileen’s influence on George’s work shouldn’t be under-estimated. Meeting her late in her life – a decade after George’s death – she would walk amongst the sculptures, laid out on plinths in a cavernous Victorian former malting attached to their house, and place her hands intuitively on every undercut and turn (the wearing of rings was strictly forbidden!). George resolutely worked alone – no assistants, no power tools, only mallets and chisels and cassettes of classical music and operatic arias for company – but the confluence between their work speaks to a shared vision. We are delighted to include in this selection a painting by Eileen alongside a drawing of George’s, both made at their beloved Isle of Purbeck, where they had holidayed (and found inspiration, in the fields, quarries and shore) every year since the late 1930s. Seen side by side, these works could almost be by the same hand. George’s drawings, mainly of the rock formations of the coast that were the source of his material, whilst studies in sculptural form, have a painter’s confident flow: equally, Eileen’s paintings, whilst more concerned with the wider landscape, have a certain sculptural feel to their construction, even though, in the end, they concern themselves more with colour and abstract form, in the manner of Ivon Hitchens or Patrick Heron, both of whom she admired. The last few years have seen something of a revival in interest in George Kennethson’s work. After all, this is an artist whose work sits very comfortably – and beautifully – in Britain’s best small museum, Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, alongside Constantin Brancusi and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. There are now two monographs on the artist, the most recent written by the eminent critic Richard Cork. Eileen Guthrie’s work, on the other hand, still remains something of a secret, her last public exhibitions being held almost 40 years ago now. We hope that this brief glimpse will be the beginning of her revival, as well as a testament an artistic partnership that was very much of its time, yet resonates with beauty today.

§ George Kennethson (British 1910-1994) Girl's Back with Curled Hair - Study for Sculpture, circa 1960 ink and wash on paperDimensions:16cm x 12.5cm (6 3/8in x 4 7/8in)Provenance:ProvenanceThe Estate of the Artist.Note: LiteratureHucker, Simon. George Kennethson: A Modernist Rediscovered. London: Merrell Publishers Limited, 2004, p.14, illustrated. George Kennethson (or Arthur Mackenzie as he was, Kennethson being the name he adopted in the early 1970s in order to separate his artistic practice from his role as the art master at Oundle School) met Eileen Guthrie in 1931 at the Royal Academy Schools in London. Intriguingly both were painting students, although in George’s case, the teaching at the still very academic Academy mainly had the effect of turning him into a sculptor, something he was already considering by his final year when the pair of them met [although one of his sons recalls Kennethson generously saying that the reason he became a sculptor was that Eileen was by far the better painter].George had come from a cultured, literary family. Eileen’s father and grandfather were architects and her mother was an accomplished pianist, who had studied at the Royal College of Music [Eileen herself had been taught piano by Gustav Holst when she was young]. And so, like many of their circle, Eileen and George were left-wing in their politics, interested in all things avant-garde in art, music and literature, and looked to Paris for inspiration. As young artists they both revered Cezanne. On their first trip together to the French capital, George tracked down the work of sculptors Maillol, Zadkine and Brancusi. And Eileen no doubt sought out the work of Bonnard, whose influence, both in composition and technique, can be traced in her work. They returned, in 1937, where they saw Picasso’s recently completed Guernica, which moved them both, artistically and politically. Like many artists of their generation, their lives and careers were profoundly affected by the Second World War. The Kennethsons were committed pacifists. A year before war broke out, they had moved to the quiet Berkshire village of Uffington, watched over by its ancient, curiously abstract White Horse, cut into the chalk of the nearby Downs, and so in away had already withdrawn from the political storm of the late 30s. The local villagers had no issues with the Kennethsons’ avowed pacifism: they were artists, after all, so they expected them to be different. Whilst they passed the war in rural seclusion, conflict does seep into Kennethson’s sculpture, such as sculptures of travellers, with staffs and backpacks, or men carrying mattresses down to the local forge – images glimpsed out of the studio window, but now transformed into a moving response to the refugees that war inevitably creates. The couple took in both evacuees from the Blitz and the occasional European refugee (and much later in the 1980s, Kennethson returned to this theme as a response to the migrations forced by famine in Ethiopia). But more than this, the War and its aftermath led to little opportunity for artists to sell their work and therefore live by their art – something that was particularly acute for the Kennethsons, who by the late 1940s had five young boys to feed. Art historians have often been critical of British artists ‘retreating’ into teaching or commercial work, whilst their counterparts in America were splashing newly made paint across acres of pristine canvas and changing the direction of modern art forever, and yet this ignores the pressures on British artists, facing a public that was already relatively indifferent to modern art already and which now was broke.It was at this point that Eileen turned her hand to making prints for textiles. She did so with incredible success – artistically at least, as there was almost as little money for interiors and design in post-war Britain as there was for at. Eileen did, however, sell her ‘Flockhart Fabrics’ range – named after her Scottish grandfather - at Primavera, a leading interiors shop on Sloane Street, as well as to family and friends. Their neighbour in Uffington, John Betjeman, also helped them to find stockists, and Eileen’s twin sister Joan would open her London flat to showcase the designs. Lucienne Day, too, introduced Eileen to Amersham Prints, contractors to the government, and her design Bird and Basket was used in 1954 to furnish the Morag Mhor, the first all-aluminium yacht in the country.George lent a hand too, on the production side, contributing to designs, working on the lino-blocks and silkscreens and helping Eileen with the considerable manual work of printing the fabrics by hand. The prints are deceptively simple, strong and sculptural, whilst retaining the required elegance and beauty. The line that one sees in her gouaches and oils find an easy home amongst the repeats of fabric design and motifs that infuse George’s sculpture – birds, leaves, architectonic flower forms – are abstracted from her landscape painting.The family moved to Oundle in 1954, to a house with a large former malting attached, which made for good, if draughty, studios. George would have been surrounded by Eileen’s fabrics – at the long settle by the kitchen table or on one of the armchairs where he would read and draw- before heading out to his studio to carve equally simple forms, with soft curves and sharp edges, into stone and alabaster, so perhaps Eileen’s influence on George’s work shouldn’t be under-estimated. Meeting her late in her life – a decade after George’s death – she would walk amongst the sculptures, laid out on plinths in a cavernous Victorian former malting attached to their house, and place her hands intuitively on every undercut and turn (the wearing of rings was strictly forbidden!). George resolutely worked alone – no assistants, no power tools, only mallets and chisels and cassettes of classical music and operatic arias for company – but the confluence between their work speaks to a shared vision. We are delighted to include in this selection a painting by Eileen alongside a drawing of George’s, both made at their beloved Isle of Purbeck, where they had holidayed (and found inspiration, in the fields, quarries and shore) every year since the late 1930s. Seen side by side, these works could almost be by the same hand. George’s drawings, mainly of the rock formations of the coast that were the source of his material, whilst studies in sculptural form, have a painter’s confident flow: equally, Eileen’s paintings, whilst more concerned with the wider landscape, have a certain sculptural feel to their construction, even though, in the end, they concern themselves more with colour and abstract form, in the manner of Ivon Hitchens or Patrick Heron, both of whom she admired. The last few years have seen something of a revival in interest in George Kennethson’s work. After all, this is an artist whose work sits very comfortably – and beautifully – in Britain’s best small museum, Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, alongside Constantin Brancusi and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. There are now two monographs on the artist, the most recent written by the eminent critic Richard Cork. Eileen Guthrie’s work, on the other hand, still remains something of a secret, her last public exhibitions being held almost 40 years ago now. We hope that this brief glimpse will be the beginning of her revival, as well as a testament an artistic partnership that was very much of its time, yet resonates with beauty today.

§ George Kennethson (British 1910-1994) Waves initialled (lower right), pencil, ink and wash on blue paperDimensions:18cm x 22cm (7 1/8in x 8 5/8in)Provenance:ProvenanceThe Estate of the Artist.Note: George Kennethson (or Arthur Mackenzie as he was, Kennethson being the name he adopted in the early 1970s in order to separate his artistic practice from his role as the art master at Oundle School) met Eileen Guthrie in 1931 at the Royal Academy Schools in London. Intriguingly both were painting students, although in George’s case, the teaching at the still very academic Academy mainly had the effect of turning him into a sculptor, something he was already considering by his final year when the pair of them met [although one of his sons recalls Kennethson generously saying that the reason he became a sculptor was that Eileen was by far the better painter].George had come from a cultured, literary family. Eileen’s father and grandfather were architects and her mother was an accomplished pianist, who had studied at the Royal College of Music [Eileen herself had been taught piano by Gustav Holst when she was young]. And so, like many of their circle, Eileen and George were left-wing in their politics, interested in all things avant-garde in art, music and literature, and looked to Paris for inspiration. As young artists they both revered Cezanne. On their first trip together to the French capital, George tracked down the work of sculptors Maillol, Zadkine and Brancusi. And Eileen no doubt sought out the work of Bonnard, whose influence, both in composition and technique, can be traced in her work. They returned, in 1937, where they saw Picasso’s recently completed Guernica, which moved them both, artistically and politically. Like many artists of their generation, their lives and careers were profoundly affected by the Second World War. The Kennethsons were committed pacifists. A year before war broke out, they had moved to the quiet Berkshire village of Uffington, watched over by its ancient, curiously abstract White Horse, cut into the chalk of the nearby Downs, and so in away had already withdrawn from the political storm of the late 30s. The local villagers had no issues with the Kennethsons’ avowed pacifism: they were artists, after all, so they expected them to be different. Whilst they passed the war in rural seclusion, conflict does seep into Kennethson’s sculpture, such as sculptures of travellers, with staffs and backpacks, or men carrying mattresses down to the local forge – images glimpsed out of the studio window, but now transformed into a moving response to the refugees that war inevitably creates. The couple took in both evacuees from the Blitz and the occasional European refugee (and much later in the 1980s, Kennethson returned to this theme as a response to the migrations forced by famine in Ethiopia). But more than this, the War and its aftermath led to little opportunity for artists to sell their work and therefore live by their art – something that was particularly acute for the Kennethsons, who by the late 1940s had five young boys to feed. Art historians have often been critical of British artists ‘retreating’ into teaching or commercial work, whilst their counterparts in America were splashing newly made paint across acres of pristine canvas and changing the direction of modern art forever, and yet this ignores the pressures on British artists, facing a public that was already relatively indifferent to modern art already and which now was broke.It was at this point that Eileen turned her hand to making prints for textiles. She did so with incredible success – artistically at least, as there was almost as little money for interiors and design in post-war Britain as there was for at. Eileen did, however, sell her ‘Flockhart Fabrics’ range – named after her Scottish grandfather - at Primavera, a leading interiors shop on Sloane Street, as well as to family and friends. Their neighbour in Uffington, John Betjeman, also helped them to find stockists, and Eileen’s twin sister Joan would open her London flat to showcase the designs. Lucienne Day, too, introduced Eileen to Amersham Prints, contractors to the government, and her design Bird and Basket was used in 1954 to furnish the Morag Mhor, the first all-aluminium yacht in the country.George lent a hand too, on the production side, contributing to designs, working on the lino-blocks and silkscreens and helping Eileen with the considerable manual work of printing the fabrics by hand. The prints are deceptively simple, strong and sculptural, whilst retaining the required elegance and beauty. The line that one sees in her gouaches and oils find an easy home amongst the repeats of fabric design and motifs that infuse George’s sculpture – birds, leaves, architectonic flower forms – are abstracted from her landscape painting.The family moved to Oundle in 1954, to a house with a large former malting attached, which made for good, if draughty, studios. George would have been surrounded by Eileen’s fabrics – at the long settle by the kitchen table or on one of the armchairs where he would read and draw- before heading out to his studio to carve equally simple forms, with soft curves and sharp edges, into stone and alabaster, so perhaps Eileen’s influence on George’s work shouldn’t be under-estimated. Meeting her late in her life – a decade after George’s death – she would walk amongst the sculptures, laid out on plinths in a cavernous Victorian former malting attached to their house, and place her hands intuitively on every undercut and turn (the wearing of rings was strictly forbidden!). George resolutely worked alone – no assistants, no power tools, only mallets and chisels and cassettes of classical music and operatic arias for company – but the confluence between their work speaks to a shared vision. We are delighted to include in this selection a painting by Eileen alongside a drawing of George’s, both made at their beloved Isle of Purbeck, where they had holidayed (and found inspiration, in the fields, quarries and shore) every year since the late 1930s. Seen side by side, these works could almost be by the same hand. George’s drawings, mainly of the rock formations of the coast that were the source of his material, whilst studies in sculptural form, have a painter’s confident flow: equally, Eileen’s paintings, whilst more concerned with the wider landscape, have a certain sculptural feel to their construction, even though, in the end, they concern themselves more with colour and abstract form, in the manner of Ivon Hitchens or Patrick Heron, both of whom she admired. The last few years have seen something of a revival in interest in George Kennethson’s work. After all, this is an artist whose work sits very comfortably – and beautifully – in Britain’s best small museum, Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, alongside Constantin Brancusi and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. There are now two monographs on the artist, the most recent written by the eminent critic Richard Cork. Eileen Guthrie’s work, on the other hand, still remains something of a secret, her last public exhibitions being held almost 40 years ago now. We hope that this brief glimpse will be the beginning of her revival, as well as a testament an artistic partnership that was very much of its time, yet resonates with beauty today.

§ George Kennethson (British 1910-1994) Father and Child, 1960s English alabasterDimensions:45.7cm high, 33cm wide, 25.5cm deep (18in high, 13in wide, 10in deep)Provenance:ProvenanceThe Estate of the Artist.Note: George Kennethson (or Arthur Mackenzie as he was, Kennethson being the name he adopted in the early 1970s in order to separate his artistic practice from his role as the art master at Oundle School) met Eileen Guthrie in 1931 at the Royal Academy Schools in London. Intriguingly both were painting students, although in George’s case, the teaching at the still very academic Academy mainly had the effect of turning him into a sculptor, something he was already considering by his final year when the pair of them met [although one of his sons recalls Kennethson generously saying that the reason he became a sculptor was that Eileen was by far the better painter].George had come from a cultured, literary family. Eileen’s father and grandfather were architects and her mother was an accomplished pianist, who had studied at the Royal College of Music [Eileen herself had been taught piano by Gustav Holst when she was young]. And so, like many of their circle, Eileen and George were left-wing in their politics, interested in all things avant-garde in art, music and literature, and looked to Paris for inspiration. As young artists they both revered Cezanne. On their first trip together to the French capital, George tracked down the work of sculptors Maillol, Zadkine and Brancusi. And Eileen no doubt sought out the work of Bonnard, whose influence, both in composition and technique, can be traced in her work. They returned, in 1937, where they saw Picasso’s recently completed Guernica, which moved them both, artistically and politically. Like many artists of their generation, their lives and careers were profoundly affected by the Second World War. The Kennethsons were committed pacifists. A year before war broke out, they had moved to the quiet Berkshire village of Uffington, watched over by its ancient, curiously abstract White Horse, cut into the chalk of the nearby Downs, and so in away had already withdrawn from the political storm of the late 30s. The local villagers had no issues with the Kennethsons’ avowed pacifism: they were artists, after all, so they expected them to be different. Whilst they passed the war in rural seclusion, conflict does seep into Kennethson’s sculpture, such as sculptures of travellers, with staffs and backpacks, or men carrying mattresses down to the local forge – images glimpsed out of the studio window, but now transformed into a moving response to the refugees that war inevitably creates. The couple took in both evacuees from the Blitz and the occasional European refugee (and much later in the 1980s, Kennethson returned to this theme as a response to the migrations forced by famine in Ethiopia). But more than this, the War and its aftermath led to little opportunity for artists to sell their work and therefore live by their art – something that was particularly acute for the Kennethsons, who by the late 1940s had five young boys to feed. Art historians have often been critical of British artists ‘retreating’ into teaching or commercial work, whilst their counterparts in America were splashing newly made paint across acres of pristine canvas and changing the direction of modern art forever, and yet this ignores the pressures on British artists, facing a public that was already relatively indifferent to modern art already and which now was broke.It was at this point that Eileen turned her hand to making prints for textiles. She did so with incredible success – artistically at least, as there was almost as little money for interiors and design in post-war Britain as there was for at. Eileen did, however, sell her ‘Flockhart Fabrics’ range – named after her Scottish grandfather - at Primavera, a leading interiors shop on Sloane Street, as well as to family and friends. Their neighbour in Uffington, John Betjeman, also helped them to find stockists, and Eileen’s twin sister Joan would open her London flat to showcase the designs. Lucienne Day, too, introduced Eileen to Amersham Prints, contractors to the government, and her design Bird and Basket was used in 1954 to furnish the Morag Mhor, the first all-aluminium yacht in the country.George lent a hand too, on the production side, contributing to designs, working on the lino-blocks and silkscreens and helping Eileen with the considerable manual work of printing the fabrics by hand. The prints are deceptively simple, strong and sculptural, whilst retaining the required elegance and beauty. The line that one sees in her gouaches and oils find an easy home amongst the repeats of fabric design and motifs that infuse George’s sculpture – birds, leaves, architectonic flower forms – are abstracted from her landscape painting.The family moved to Oundle in 1954, to a house with a large former malting attached, which made for good, if draughty, studios. George would have been surrounded by Eileen’s fabrics – at the long settle by the kitchen table or on one of the armchairs where he would read and draw- before heading out to his studio to carve equally simple forms, with soft curves and sharp edges, into stone and alabaster, so perhaps Eileen’s influence on George’s work shouldn’t be under-estimated. Meeting her late in her life – a decade after George’s death – she would walk amongst the sculptures, laid out on plinths in a cavernous Victorian former malting attached to their house, and place her hands intuitively on every undercut and turn (the wearing of rings was strictly forbidden!). George resolutely worked alone – no assistants, no power tools, only mallets and chisels and cassettes of classical music and operatic arias for company – but the confluence between their work speaks to a shared vision. We are delighted to include in this selection a painting by Eileen alongside a drawing of George’s, both made at their beloved Isle of Purbeck, where they had holidayed (and found inspiration, in the fields, quarries and shore) every year since the late 1930s. Seen side by side, these works could almost be by the same hand. George’s drawings, mainly of the rock formations of the coast that were the source of his material, whilst studies in sculptural form, have a painter’s confident flow: equally, Eileen’s paintings, whilst more concerned with the wider landscape, have a certain sculptural feel to their construction, even though, in the end, they concern themselves more with colour and abstract form, in the manner of Ivon Hitchens or Patrick Heron, both of whom she admired. The last few years have seen something of a revival in interest in George Kennethson’s work. After all, this is an artist whose work sits very comfortably – and beautifully – in Britain’s best small museum, Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, alongside Constantin Brancusi and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. There are now two monographs on the artist, the most recent written by the eminent critic Richard Cork. Eileen Guthrie’s work, on the other hand, still remains something of a secret, her last public exhibitions being held almost 40 years ago now. We hope that this brief glimpse will be the beginning of her revival, as well as a testament an artistic partnership that was very much of its time, yet resonates with beauty today.

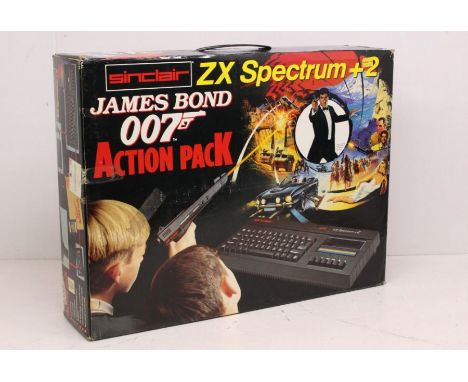

Sinclair: A boxed Sinclair ZX Spectrum +2: James Bond Action Pack. Containing: Light Gun, Power Supply, Instruction Manual, ZX Spectrum +2 Action Pack, Mission Game Instructions and Software Audio Tape. Contents are untested for working order. Appear in good condition. Original box. Edge and shelf wear as expected with age. Please assess photographs.

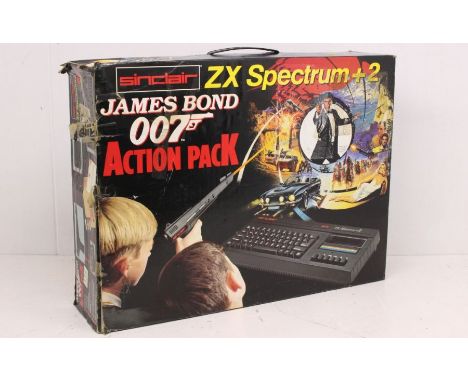

Sinclair: A boxed Sinclair ZX Spectrum +2: James Bond Action Pack. Containing: Light Gun, Power Supply, Instruction Manual, ZX Spectrum +2 Action Pack, Mission Game Instructions and Software Audio Tape. Contents are untested for working order. Appear in generally good condition. Original box. Edge and shelf wear as expected with age, some crushing and tearing to box. One cassette missing. Please assess photographs.

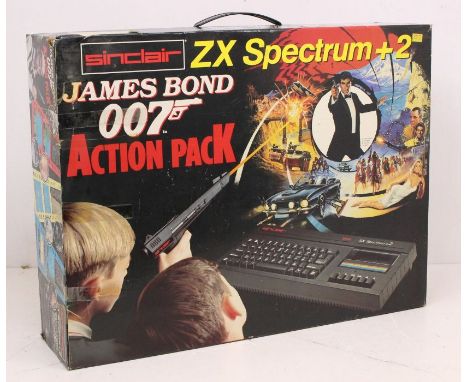

Sinclair: A boxed Sinclair ZX Spectrum +2: James Bond Action Pack. Containing: Light Gun, Power Supply, Instruction Manual, ZX Spectrum +2 Action Pack, and Software Audio Tape. Contents are untested for working order. Appear in good condition. Original box. Edge and shelf wear as expected with age. Missing outer box for Spectrum keyboard. Please assess photographs.

An Aster Hobbies of Japan circa 2008 Gauge 1 live steam spirit fired model of a British Railways Castle Class No. 5070 Sir Daniel Gooch 4-6-0 locomotive and tender, finished in British Railways green, model has had very little use, and is supplied in the original card kit form Astor Hobbies box, serial number 216/280 with matching plaque to the underside of tender, complete with an Aster Hobbies manual and catalogueBuilder and painter names not known.The motion wheels are stiff but turn freely. Have not identified any missing parts.

One tray & one box Hornby-Dublo 3-rail track, approx. quantities: Straights: 37 full, 16 halves & 12 qtrs; Curves: 18 large radius, 49 standard curves & 8 halves. One isolating, 18 L/H & 11 R/H manual points; 3 diamond crossings; 7 electric uncoupling; 2 manual; 5 asstd switches & packet of coupling rods for switches. All (VG-E)

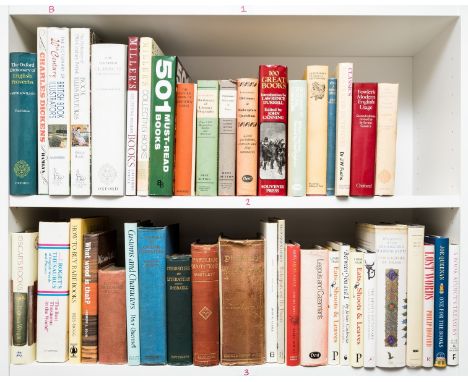

NO RESERVE Edlin (Herbert L.) What wood is that? A manual of wood identification, mounted wood samples, original cloth, dust-jacket, 1988 § Bland (David) A History of Book Illustrations, colour frontispiece, plates and illustrations, original cloth, fractional bumping to corners and extremities, price-clipped dust-jacket, slight creasing to edges, 1959 § D'Israeli (I) Curiosities of Literature, portrait frontispiece, scattered spotting, cracked hinges, original cloth, slight bumping and chipping to corners and extremities, 1867; and others, v.s., (c.90)

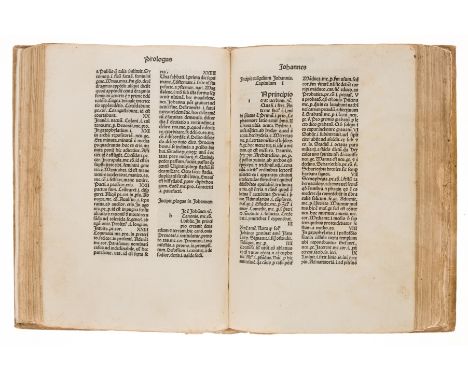

Marchesinus (Johannes) Mammotrectus super Bibliam, collation: a-y8 1-68 7 A10 B C8, 259 ff. (of 260, lacking C1), A1 blank, 38 lines and headline, Gothic type, initial spaces with guide-letters, water- / damp-staining, more severely so at end, last c.10ff. with loss of text and repaired, worming as far as d1, with slight loss of text, a little worming to inner margins of y6-a5 occasionally touching the odd letter, repairs, mostly marginal, some spotting, lightly browned, 17th century vellum, rebacked, preserving original backstrip in compartments, soiled, [BMC V, 180; Goff M-239; HC 10559*; GW M20809; Bod-inc M-085; BSB-Ink M-158; ISTC im00239000], 4to, Venice, Nicolaus Jenson, 23 September, 1479. sold not subject to return. ⁂ A manual for the clergy, containing etymological and grammatical explanations of words in the Bible, along with the liturgical hours, arranged in the order of the Bible and the church year. It is one of the most important Franciscan texts of the later Middle Ages.

A mid-century Rolex Shock-Resisting stainless steel mid-size manual wind wrist watch, 1950s, the 24.5mm. silvered dial with minute tracks, centre seconds, gilt Rolex crown and lumed gilt dot and batons markers with Arabic numerals at 2,4,6,8 and 10, the 30mm. case with plain crown, the signed Dennison for Rolex caseback numbered 12324 2789, signed 15 Rubis movement, no. 68000, with later black leather strap, in a blue flock Rolex box, * Condition: Winds and runs. Hands adjust correctly. One securing screw is detached from the movement but present - it appears to lack the lower threaded section, so cannot be re-fitted. Silvering to dial has dulled and light surface scratches to centre. Luming to batons and dots has dulled and degraded. There is no luming to the hands. Some scratching to plastic crystal. Expected scratching and small nicks to case from regular use. Strap good but not original or by Rolex. Box probably later.

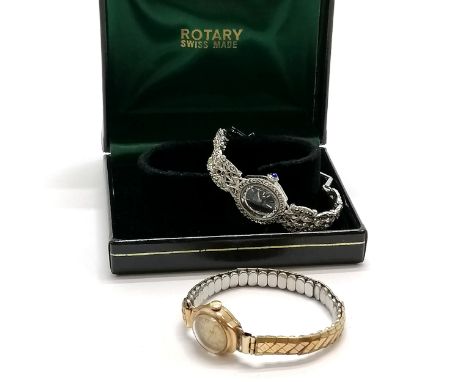

A Record de Luxe 9ct gold ladies bracelet watch, manual wind, silvered 16mm. dial with gilt batons and Arabic numerals at 12 and 6, on a brushed and textured gold bracelet, hallmarked Birm. 1973. * Condition: Does not run. Dial good. Case good but presentation inscription to caseback. Bracelet good.

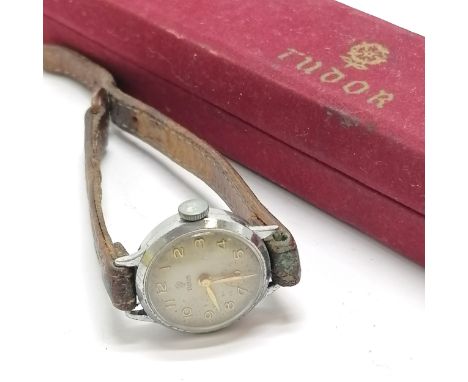

A 9ct gold cased ladies watch by Tudor, hallmarked Chester 1955, signed cal. 2325 15J manual movement, 18mm. silvered dial with gilt Arabic numerals and subsidiary seconds; together with two other 1950s-60s gold cased ladies watches by Tissot (14ct) and Record (9ct), faults; and five other vintage ladies wrist watches, faults. (8)* Condition: - Tudor: Winds but runs only briefly. Otherwise in good condition, although glass is cracked. Strap poor.- Record: Winds but not running. Caseback with presentation inscription. Case and dial good. Tarnish spots to hands. Later strap, good.- Tissot: Lacks crown - for repair.- Others: All with faults - for spares/repair.

A mid-century 14ct rose gold gentleman's wristwatch by Helvetia of Switzerland, London 1946, signed 800C 17 jewel manual movement, the silvered dial with gilt Arabic numerals and outer minute track with Arabic five seconds markers, gilt sword hands and red seconds hand, the 33mm. case with inscribed caseback, black leather strap. * Condition: Winds and runs. Dial has some small green tarnish spots to the silvering and a few discoloured spots. Spotting to gilt hands. Some scratches to the crystal, mainly to edges. Caseback with engraved inscription. Later strap - some wear and creasing but still good.

An early Rolex 18ct gold cased gentleman's manual wristwatch, caseback engraved and dated 27.2.21, signed, engine turned Rolex 15 jewel movement, silvered dial signed 'Rolex', with sub seconds at six, black printed Arabic numerals with outer minute track, 32mm. polished case, later black leather strap. * Condition: Winds and runs. Some old oil deposits to movement and a little surface rust along one edge. Tools marks from opening to case edge. Dial VG with a little faint spotting. Light scratching to crystal. Caseback engraved and has two small dings but overall good.

Four mid-century 9ct gold cased wrist watches, all manual wind, comprising an Art Deco style gents watch, Chester 1932, with silvered square Arabic dial and Rone 15J movement, later gold plated Fixo-Flex strap; two ladies watches with circular silvered Arabic dials, one by Benson with Swiss 15J movement, the other by Record, London 1929, with signed movement, later plated straps; and an Art Deco period cocktail watch with octagonal champagne dial, unsigned, gilt metal strap, some faults. (4)* Condition: - Art Deco square dial: Dial tarnished. Lacks subsidiary seconds hand. Some surface rust spots to movement - running when catalogued. Case good, Strap replaced.- Benson: Not running. Dial tarnished and with light scratching. Small ding to case front. Strap replaced.- Record: Running when catalogued. A little rust spotting to bright steel parts to movement. Dial tarnished. Scratching to glass. Several dings to case front and back. Strap replaced.- Octagonal: Running when catalogued. A little light rust spotting to movement. Dial tarnished and some case wear around edges. Ding to case back.

A vintage Bulova rolled gold and stainless steel manual wrist watch, 1950s, the 21mm. silvered square dial with subsidiary crosshair seconds at six, paste dot markers and red faux-ruby baton markers at the quarters, the 25.5mm. rolled gold case with claw lugs and stainless steel caseback, no. 1942697, later black goatskin strap. * Condition: Winds and in running order when catalogued. A scattering of tiny spots to dial, tiny scratch above the subsidiary seconds and dulling to three of the paste markers, Wear to rolled gold on top of lugs and edge of crown. Strap VG.

A Beuche-Girod ladies 18ct gold cased cocktail watch, London import hallmarks, 1936, with signed 17J manual wind movement, black dial with gilt batons and Arabic quarter numerals, 13.5mm. tonneau shaped case, no. 615816, brown leather strap. * Condition: Watch is not currently running. Dial has some spotting and light blistering to the paint and a scratch to the left side. Case good overall, but caseback has engraved name and date. Strap worn.

A vintage 9ct gold ladies Rodania manual wind bracelet watch, hallmarked London 1969, the circular, 14mm. silvered dial with gilt baton markers, on a flexible, bark effect strap bracelet with slide clasp, 16.3cm. long overall. * Condition: Winds and runs. Good condition overall. Dial and glass good. Strap good and clasp functions correctly.

-

80915 item(s)/page