GOLD RING. An 18ct. gold ring set a row of two (of three) brilliant cut diamonds. Size L/M. Approx. 5.8g. Please note that all items in this auction are previously owned & are offered on behalf of private vendors. If detail on condition is required on any lot(s) PLEASE ASK FOR A CONDITION REPORT BEFORE BIDDING. The absence of a condition report does not imply the lot is perfect.WE CAN SHIP THIS LOT, but NOT if part of a large, multiple lots purchase.

We found 563972 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 563972 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

563972 item(s)/page

GOLD RINGS. A 9ct. gold diamond & garnet set, strap & buckle ring & a 9ct. gold signet ring. Please note that all items in this auction are previously owned & are offered on behalf of private vendors. If detail on condition is required on any lot(s) PLEASE ASK FOR A CONDITION REPORT BEFORE BIDDING. The absence of a condition report does not imply the lot is perfect.WE CAN SHIP THIS LOT, but NOT if part of a large, multiple lots purchase.

GOLD RINGS ETC. A 9ct. white gold ring set a blue stone & a 9ct. yellow gold ring set with small emeralds & one other green stone. Also, a silver & smoky quartz dress ring. Please note that all items in this auction are previously owned & are offered on behalf of private vendors. If detail on condition is required on any lot(s) PLEASE ASK FOR A CONDITION REPORT BEFORE BIDDING. The absence of a condition report does not imply the lot is perfect.WE CAN SHIP THIS LOT, but NOT if part of a large, multiple lots purchase.

AMETHYST RING. A 9ct. gold amethyst set dress ring. Size M/N. Please note that all items in this auction are previously owned & are offered on behalf of private vendors. If detail on condition is required on any lot(s) PLEASE ASK FOR A CONDITION REPORT BEFORE BIDDING. The absence of a condition report does not imply the lot is perfect.WE CAN SHIP THIS LOT, but NOT if part of a large, multiple lots purchase.

ART DECO RING. An 18ct. gold & platinum ring set a row of three diamonds between sapphires. Size N. Please note that all items in this auction are previously owned & are offered on behalf of private vendors. If detail on condition is required on any lot(s) PLEASE ASK FOR A CONDITION REPORT BEFORE BIDDING. The absence of a condition report does not imply the lot is perfect.WE CAN SHIP THIS LOT, but NOT if part of a large, multiple lots purchase.

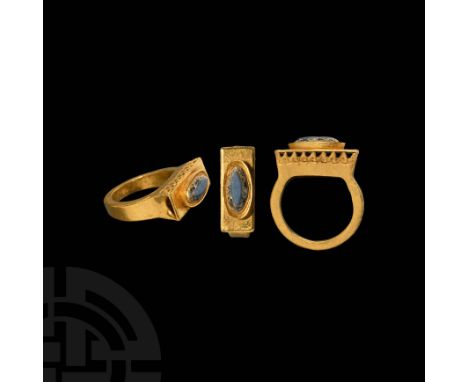

4th-6th century AD. A gold ring with rectangular-section hoop, rectangular bezel with openwork sides, u-section at the shorter ends, zigzags to the longer edges with engraved pellet in each and swag between, a bevelled rectangular plate with raised ellipsoidal cell set with a nicolo gemstone. Cf. Content, D.J., Ruby, Sapphire & Spinel: An Archaeological, Textual and Cultural Study, Part II, Belgium, 2016, pp.82-85, for a broadly comparable architectural form. 9.54 grams, 29.44mm overall, 18.40mm internal diameter (approximate size British O, USA 7, Europe 14.98, Japan 14) (1"). Property of a London gentleman; acquired on the UK art market in 2012; previously in a 1970s collection; accompanied by a positive scientific statement from Striptwist Limited, a London-based company run by historical precious metal specialist Dr Jack Ogden, reference number 210714; this lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by AIAD certificate number no.11011-180889. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] Very fine condition.

1st millennium BC. An electrum gold ring or adornment with rectangular-section hoop, expanding at the shoulders to form a ribbed bezel. 5.97 grams, 20.74mm overall, 16.04mm internal diameter (approximate size British G, USA 3 1/4, Europe 4.92, Japan 4) (3/4"). From the Alexander Cotton collection, Hampshire, UK, 1970s. Fine condition.

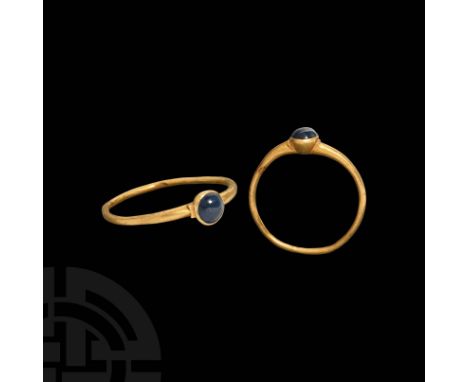

13th-14th century AD. A gold ring formed with round-section band and projecting cup bezel with a circular sapphire set en cabochon. Cf. Chadour, A., Rings, The Alice and Louis Koch Collection, Leeds, 1994, p.172, item 566; cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1811, for similar; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. ESS-0E1E7B; PAS-817076; YORYM-824004; for similar. 1.93 grams, 23.64mm overall, 18.78mm internal diameter (approximate size British Q, USA 8, Europe 17.49, Japan 16) (1"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. The so-called stirrup rings were in fashion from the 12th-14th century AD in England, often worn by ecclesiastical dignitaries. From the 7th century AD onwards, sapphires were worn by bishops as a symbol of the papal authority invested in them. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition.

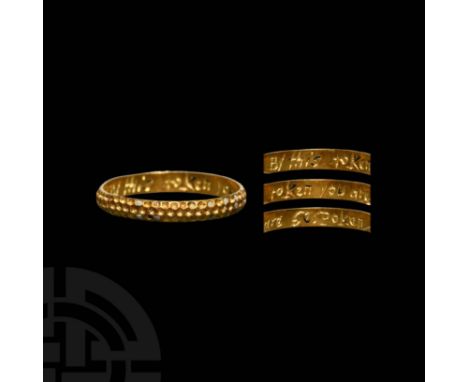

18th century AD. A gold D-section band, the external face ornamented with three circumferential rows of fine dimples, the interior inscribed 'By this token you are bespoken' in script characters. See Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.28, for this posie, sourced from 'The Best and Compleatest Academy of Compliments yet extant. Being wit and mirth improv'd by the most elegant expressions used in the art of courtship...' London, printed and sold by William Dicey, 1750; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. LON-AA2432, for a worn ring which appears to have three rows of dimples also, dated 16th-17th century AD. 1.20 grams, 18.10mm overall, 16.44mm internal diameter (approximate size British J 1/2, USA 5, Europe 9.32, Japan 9) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Fine condition.

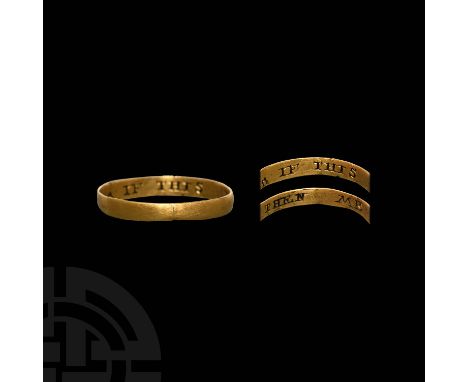

16th-17th century AD. A slender gold D-section annular band with plain outer face, the inner face inscribed 'IF THIS THEN ME' in seriffed capitals with small quatrefoil before; remains of niello fill. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.51, for the same inscription, 'me' spelt 'mee'; cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.413, for this inscription with spelling variation, dated 17th-18th century; museum number AF.1286, for this inscription with spelling variation, dated 16th-17th century AD; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id.LVPL-AD7284, for similar, dated 1550-1650; id. 1.12 grams, 17.40mm overall, 16.23mm internal diameter (approximate size British K, USA 5 1/4, Europe 9.95, Japan 9) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. Capital letter inscriptions are thought to have been more common before the mid 17th century AD, when inscriptions in italic script gained popularity. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Fine condition.

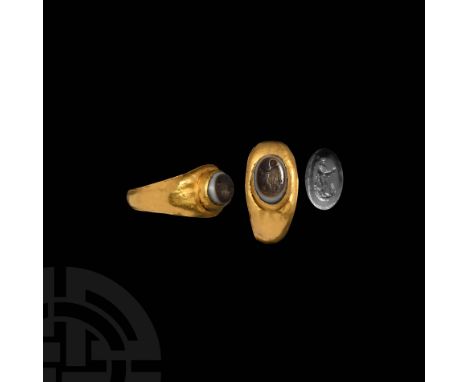

1st-2nd century AD. A gold finger ring with ellipsoid cell to the bezel, inset onyx gemstone with intaglio figure of Mercury in travelling cloak (sagum) holding out his coin-purse (marsupium"). Cf. Chadour, A.B., Rings. The Alice and Louis Koch Collection, volume I, Leeds, 1994, item 285, for type. 3.66 grams, 24.72mm overall, 21.01mm internal diameter (approximate size British T, USA 9 1/2, Europe 21.26, Japan 20) (1"). From the private collection of a Russian gentleman living in London; acquired from a Chelsea collector in the 2000s; the Chelsea collection having been formed from 1970-1990s. Very fine condition. A large wearable size.

Dated [16]68 AD. A mourning ring composed of a gold D-section annular band, the external face engraved with a partial stylised skull, the inner face inscribed: 'P.S obyt 14 Sept 68' in script characters, with maker's monogram 'TC' in shield-shaped cartouche, likely for maker Thomas Cockram. Cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1533, for a parallel by the same maker; cf. museum numbers AF.1539, AF.1535, AF.1541, dated 17th century, for comparable examples by other makers. 3.10 grams, 20.25mm overall, 18.15mm internal diameter (approximate size British P, USA 7 1/2, Europe 16.23, Japan 15) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. London jeweller Thomas Cockram of the London Goldsmiths Company, is presumed to have been active from 1646 AD; the ring suggests the year 1668 for the date of manufacture. The traditional practice of bequeathing rings belonging to the deceased to the family and friends they left behind was gradually replaced in the 16th and 17th centuries, when it became preferable for the deceased to leave a sum of money with which memorial, commemorative or mourning rings could be purchased. In the later part of the 17th century, such rings were distributed at funeral services, where they were worn in memory of the deceased. 'Memento mori' inscriptions and popular devices such as skulls, crossbones and hourglasses became fashionable on jewellery and in print, prompting the reader or viewer to ponder the brevity of life and the necessity of preparing the soul for death. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition, some wear.

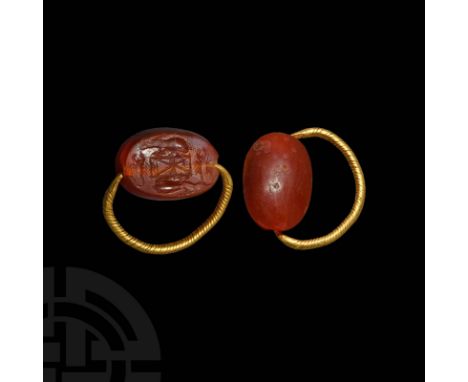

6th-4th century BC. A gold ring with tapering round-section hoop with faux twisted wire design, carnelian swivel scaraboid with intaglio design composed of scorpions and ibex bordering a central rectangular panel with X-motif, a single letter in each quadrant 'N E A H'. Cf. The British Museum, museum number 133320, for comparable items. 4.89 grams, 24.90mm overall, 20.90 x 12.47mm internal diameter (approximate size British H, USA 3 3/4, Europe 6.18, Japan 6) (1"). From a deceased Japanese collector, 1970-2015; this lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by AIAD certificate number no.11029-181788. Fine condition.

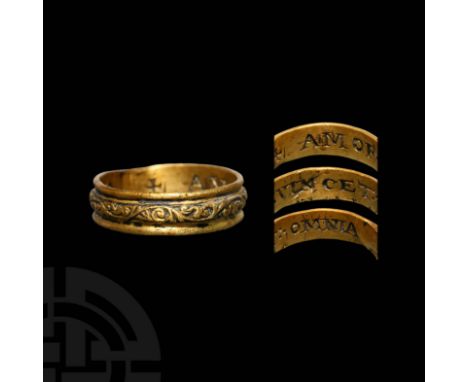

16th-18th century AD. A gold ring with D-section band, two slender c-section circumferential channels to top and bottom of external face, framing a foliate frieze with remains of niello inlay; Latin inscription to the inner face in seriffed capitals: '+ AMOR VINCET OMNIA' ('Love Conquers All'), the words separated by triangles composed of three dots. See Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p1. for this inscription and for multiple variations on the 'Amor Vincit' posie; cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.460, for a different ring with the same inscription and very similar lettering and punctuation, dated 16th-early 17th century AD.; cf. The Portable antiquities Scheme Database, id. YORYM-B0EB9B, for a very similar ring with the same posie, dated 1500-1700 AD; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. GLO-55A844, for a very similar ring design, dated 1650-1740 AD. 3.34 grams, 18.61mm overall, 16.02mm internal diameter (approximate size British K, USA 5 1/4, Europe 9.95, Japan 9) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. 'Amor Vincit Omnia' was perhaps the most popular 'stock' motto engraved onto posy rings bearing Latin inscriptions; it was the motto engraved on a brooch worn by the flirtatious Prioress in Chaucer's Prologue to the 'Canterbury Tales', penned around 1390 AD. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Fair condition.

10th-11th century AD. A gold annular band with rectangular-section hoop, plaited wire bezel and shoulders composed of three facetted gold wire strands hammered together at the lower shoulder, with an interesting ancient stepped joint to the band. Cf. The British Museum, museum number 1870,0402.77, for a ring of similar style and date; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. SUSS-C6C345; SF-1E15D7; WAW-0C7587; WILT-C90DD5; GLO-37A922 and YORYM-F67716, for rings of similar style and date; cf. Oman, C., British Rings 800-1914, London, 1974, pl. 12, fig. D for similar; see Graham-Campbell, J., The Cuerdale Hoard and related Viking-Age silver and gold from Britain and Ireland in the British Museum, London, 2011, pp.259-263. 6.86 grams, 27.28mm overall, 22.02 x 13.73mm internal diameter, (approximate size British K 1/2, USA 5 1/2, Europe 10.58, Japan 10) (1"). Found while searching with a metal detector near the village of Sutton, Kent, UK, by Paul Smith on Monday 12th August 2019; declared as treasure and disclaimed by the crown under Treasure case tracking number 2019T856; accompanied by a copy of the Portable Antiquities Scheme Report (PAS) with reference number KENT-E2042E; a copy of the Treasure Receipt from the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport; a copy a letter from the British Museum disclaiming the object to the finder; and the Report on find of Potential Treasure to HM Coroner; and a letter from the finder describing the circumstances of finding. Gold rings of this style and date are a relatively rare find, although broad parallels are known. The associated PAS report suggests a date of 'c. AD 900-1100' for this ring. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] Fine condition, hoop split, also with ancient repair.

18th century AD. A gold ring with hoop carinated around the internal face, bezel formed as twin heart-shaped cells set with turquoise coloured glass and garnet, gadrooning to the undersides, the external face of the hoop with French inscription in reserved seriffed capitals: 'MOI SEUL EN . AI . LA CLEF', ('I alone hold the key'), the words punctuated by clusters of decorative vertical notches; remains of niello infill around the lettering. Cf. The British Museum, museum numbers AF.1669 and AF.1641, for a very similar style of ring; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. HESH-4BDAD2, dated 1750-1900, for a similar style with a single heart-shaped cell. 0.97 grams, 17.34mm overall, 14.51mm internal diameter (approximate size British H, USA 3 3/4, Europe 6.18, Japan 6) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Fine condition.

2nd-3rd century AD. A gold ring with D-section hoop ornamented with lozenges, scrolled shield-shaped shoulders and oval bezel, with polished oval carnelian intaglio with image of Hermes (Greek Mercury) standing right holding a caduceus in right hand, chlamys draped over right arm, marsupium in the left hand. Cf. Ruseva-Slokoska, L., Roman Jewellery, Sofia, 1991, item 184, for this type of ring, dated 3rd century AD. 7.98 grams, 23.07mm overall, 14.52mm internal diameter (approximate size British Q 1/2, USA 8 1/4, Europe 18.12, Japan 17) (1"). Ex collection of a Surrey, UK, gentleman; acquired on the UK art market; previously on the European art market before 2000. Very fine condition.

Late-Ptolemaic Period, 664-30 BC. A grey jasper amulet formed as a frog modelled naturalistically in the round in high-relief, sitting on a discoid base; set into an antique gold ring with D-section hoop, openwork lotus flower terminals and twisted gold wire bezel. For a similar frog set in a gold ring see Christie's, Ancient Jewelry, 7 November 2011, lot 343: 'An Egyptian Agate Frog, Late Period to Ptolemaic Period, 664-30 BC'; with Jack Ogden, London, 1980. 5.48 grams, 26.56mm overall, 19.77mm internal diameter (approximate size British P, USA 7 1/2, Europe 16.23, Japan 15) (1"). Property of a London gentleman; acquired on the UK art market in 2012; previously in a 1970s collection. The frog may originally have been produced as the lid of a cosmetic vessel. Very fine condition.

18th century AD. A substantial gold D-section annular band with plain external face, internal face inscribed: 'loVe For EVer' in mixed script and capital characters. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.72, for this inscription; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id.GLO-9143B6, for a similar ring with the same inscription and script, dated c.1650-1850 AD and BH-5C4EAE, for a similar ring with same inscription and similar script dated 1600-1710 AD; cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.309, for a similar ring with the same inscription in a later script, dated 19th century AD. 5.20 grams, 21.84mm overall, 19.31mm internal diameter (approximate size British R, USA 8 1/2, Europe 18 3/4, Japan 18) (1"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition, slightly misshapen. A large wearable size.

13th century AD. A gold ring brooch formed as two pairs of addorsed beast heads, ribbed bodies, raised 'conical' ears, recessed circular eyes to receive inserts (now absent), two raised oval cells equidistant from each head set with polished amethyst cabochons, pin loop held between the beasts' mouths at the top with rounded triangular projection decorated with incised dashes, leaf-shaped pin-rest below with incised detailing, articulate tapering D-section pin with ornamental collar composed of an annulet flanked by crescents. Cf. The British Museum, museum number 2003,0703.1, for similar; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id.LIN-B824B9, for similar; cf. Egan, G. and Pritchard, F., Dress Accessories, c.1150-c.1450. Medieval Finds from Excavations in London, London: HMSO, 2002, pp.247-255. 1.42 grams, 15.1mm (1/2"). Property of a Gloucestershire, UK, gentleman; acquired by his father on the UK art market in the 1980s; thence by descent 1991. This form of ring brooch can be securely dated to the 13th century AD owing to the excavation of in-situ examples in archaeological excavations. Similar examples in silver have been declared treasure, including a brooch from Mildenhall area, Suffolk (PAS, 2004 T176), Tolpuddle, Dorset (PAS, 2011 T724), and South Gloucestershire (PAS, 2014 T856"). All were declared Treasure under the Treasure Act 1996. This lot is one of the very few examples of such brooches to have retained its pin. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] Very fine condition.

c.1580 AD. A substantial silver-gilt ring with rectangular-section hoop and oval bezel, bearing two engraved heraldic shields mounted over foil with designs in black and gold: on the left reading 'IHS' Christogram beneath an omega symbol; forget-me-nots on the right, fleur-de-lys between below, 'FGMN', 'fergiss mein nicht' or 'forget-me-not' in gold lettering above, crystal panel over bezel, etched with two conjoined shields. Cf. The V&A Museum, accession number 815-1871, for similar, dated late 16th century, Germany. 7.52 grams, 25.55mm overall, 20.15mm internal diameter (approximate size British P 1/2, USA 7 3/4, Europe 16.86, Japan 16) (1"). Property of a central London collector; acquired from a large private collection formed in the 1980s; this lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by AIAD certificate number no.11021-180871. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] Fine condition. A large, wearable size.

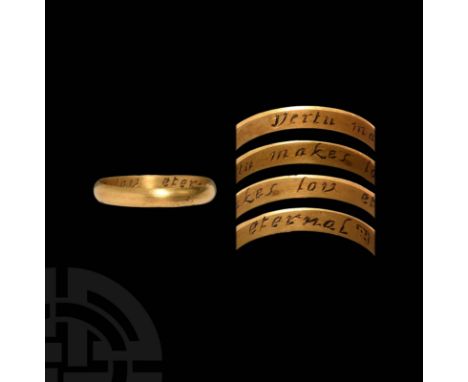

18th century AD. A gold D-section annular band with softly facetted outer face, inscription to the inner face reads 'Vertu makes lov[e] eternal' in script characters, followed by a conjoined 'RH' maker's mark in a rectangular cartouche; remains of niello inlay. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.105, for this inscription; cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.452, for a similar ring and maker's mark, maker unknown, dated 17th-18th century AD; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. SF-0A94B5; PAS-B622E7, for similar rings with the same inscription, albeit with variations in spelling, dated 1600-1799 AD. 2.13 grams, 19.73mm overall, 17.72mm internal diameter (approximate size British O 1/2, USA 7 1/4, Europe 15.61, Japan 15) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. No recorded conjoined 'RH' maker for this period, only for the 16th and very early 17th century AD. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition, a few small nicks.

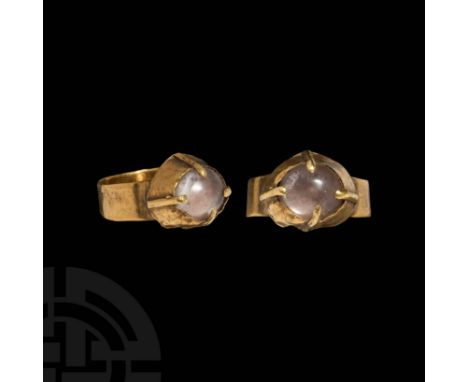

c.12th century AD. A gold finger ring comprising a flat-section hoop and conical bezel with applied claw setting; inset chrysoberyl cabochon showing asterism. Cf. Chadour, A.B., Rings. The Alice and Louis Koch Collection, volume I, Leeds, 1994, item 560, for type. 2.89 grams, 23.34mm overall, 17.28mm internal diameter (approximate size British N, USA 6 1/2, Europe 13.72, Japan 13) (1"). From the private collection of a Russian gentleman living in London; acquired from a Chelsea collector in the 2000s; the Chelsea collection having been formed from 1970-1990s. Very fine condition.

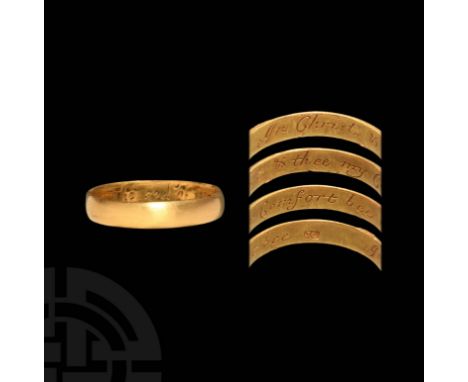

18th century AD. A substantial gold D-section annular band with plain external face, the interior inscribed: 'In Christ & thee my Comfort bee' in script characters, together with a maker's mark 'JC' in a rectangular cartouche. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, p.57, for this inscription; cf. The British Museum, museum numbers 1961,1202.329; AF.1346; AF.1353, for posy rings with the same maker's stamp, dated circa late18th century AD. 5.34 grams, 22.37mm overall, 18.92mm internal diameter (approximate size British R 1/2, USA 8 3/4, Europe 19.38, Japan 18) (1"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985; bought at the Cumberland coin fair, London, believed to have been found in Hertfordshire, UK. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition, a few small scuffs. A large wearable size.

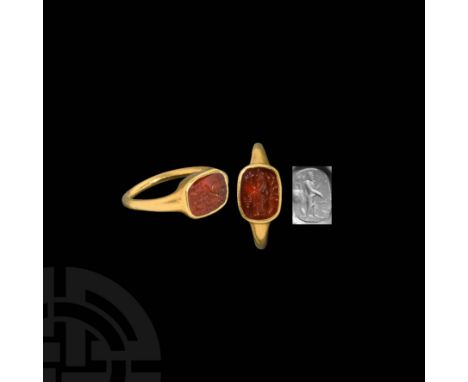

c.1st century AD. A gold ring with round-section hoop and rectangular bezel with rounded corners, set with a carnelian intaglio motif of a robed male figure standing left, sacrificing over an altar, a tree or plant to his right. 4.26 grams, 21.97mm overall, 18.14mm internal diameter (approximate size British L 1/2, USA 6, Europe 11.87, Japan 11) (1"). Property of a London gentleman; acquired on the UK art market in 2012; previously in a 1970s collection; accompanied by a positive scientific based statement from Striptwist Limited, a London-based company run by historical precious metal specialist Dr Jack Ogden, reference number 210801; this lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by AIAD certificate number no.11019-181318. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] Very fine condition.

Dated 1 January [1]709 AD. A D-section gold annular finger ring with floral and foliate ornament to outer surfaces showing traces of black enamel background; the inner face engraved in script 'Sr T Littleton Bar ob 1 Jan [1]709 aet 62' and with punched 'IB' maker's mark, possibly for the London maker J. Burridge who was active at this period. See Dictionary of National Biography, pp.1255-1256, for biographical summary; see Morant, P., The History and Antiquities of the County of Essex, Colchester, 1768, p.103; see Chancellor, F., The Ancient Sepulchral Monuments of Essex, London and Chelmsford, 1890, p.186, for details of his memorial and arms. 6.55 grams, 21.66mm overall, 17.84mm internal diameter (approximate size British O, USA 7, Europe 14.98, Japan 14) (1"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985; acquired at an antiques fair, believed to have been found in Essex, UK; this lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by AIAD certificate number no.10956-179120. Sir Thomas Littleton, 3rd Baronet, Stoke St Milborough (Shropshire) and North Ockendon (Essex), also known as Sir Thomas Poyntz (or Pointz), circa 1647-1 January 1709 (Julian calendar or 1710 Gregorian calendar), was born as second son to the 2nd Baronet but, after the early death of his older brother, he inherited the title and attended St Edmund Hall, Oxford, matriculating in 1665 and entered the Inner Temple in 1671; he was elected to the Convention of 1689 for Woodstock and served as Member of Parliament for several seats until his death. In 1697 he became Lord of the Admiralty and had acted as pallbearer at the funeral of Samuel Pepys, his predecessor; in 1698 he was elected Speaker of the House of Commons, later becoming Treasurer to the Navy, a post he held until his death. Although married, he had no children and the title became extinct upon his death. His memorial may be seen to this day in the church of St Mary in North Ockendon, Essex and is described by Chancellor who also gives details of the combined arms of Sir Thomas as: quarterly 1 and 4, argent a chevron. between three escallops sable, 2 and 3 'Pointz', within a mullet sable for difference; overall the Badge of Baronetcy and an inescutcheon gules and chevron ermine between three garbs or. Crest a Moor's head in profile couped at the shoulder proper wreathed about the temples argent and sable and a copy of a contemporary engraved portrait is included, together with extracts from other documentary references. Published sources give the year of his death as either 1709 (as on this ring) or 1710; this results from the changeover from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian in 1752; under the Julian calendar, the new year occurred 1 March, giving his death taking place in 1709; from 1752, the new year was pushed back to 1 January, resulting in his death year becoming 1710 under the new calendar rules. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Fine condition.

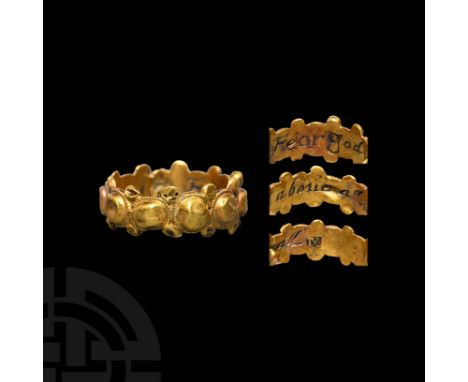

Mid 16th-early 18th century AD. A gold band ornamented with a circumferential frieze of oval bosses to the external face, faux ropework borders around, smaller domed pellets between to the top and bottom edges; the interior inscribed in italics: 'Fear god above all' in cursive script, partial remains of niello inlay, followed by stamped maker's mark 'IY[or V]' in rectangular cartouche, possibly that of John Young entered in 1760 and in use until at least 1793. Cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id.NMS-B8BCC4; BERK-118101; LIN-B6F8A3; SOM-823925; SF-3A8B11, for very similar with different inscriptions dated c.1550-1700; See Oman (1974, plate 58 c, p. 111) for a very similar example with a different inscription, dated to the early 17th century; cf. The British Museum, museum number 1942,0708.1, for broadly similar, different inscription. 2.77 grams, 18.83mm overall, 15.44mm internal diameter (approximate size British I, USA 4 1/4, Europe 7.44, Japan 7) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Fair condition.

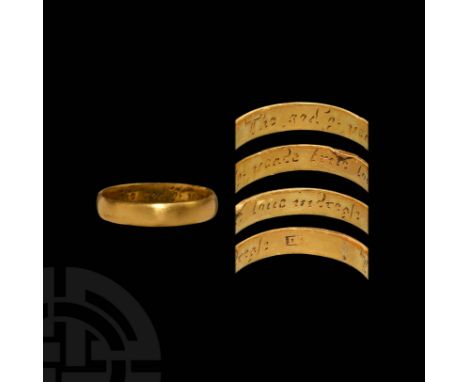

18th century AD. A gold D-section annular band with plain external face, the internal face inscribed: 'The god of peace true love increase' in script characters with remains of niello inlay; stamped with maker's mark 'IV' in rectangular cartouche, likely for the maker John Vickerman. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, p.95, for this inscription; cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1376, for a similar ring with this inscription, by another maker, and museum number AF.1375, for a similar ring with this inscription and date; museum number AF.1215, for the same maker's mark on a gold posy ring. 4.42 grams, 21.75mm overall, 19.33mm internal diameter (approximate size British S 1/2, USA 9 1/4, Europe 20.63, Japan 19) (1"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. John Vickerman's known active dates are 1768-1773 AD. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition, small scuffs at edge. A large wearable size.

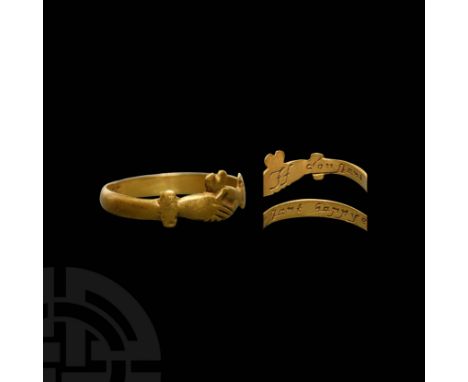

18th century AD. A gold posy or fede ring with D-section band, bezel formed as two clasping hands emergent from sleeve cuffs, a heart between above, with worn detailing to the hands and cuffs; the interior inscribed 'If constant happye' in script characters. Cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.269, for very similar ring, different inscription, with known maker dated 17th century; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. PAS-FB4D00, for similar fede design, dated 1650-1720. 1.44 grams, 18.00mm overall, 16.80mm internal diameter (approximate size British K, USA 5 1/4, Europe 9.95, Japan 9) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition. Rare.

13th-14th century AD and later. A gold stirrup ring with carinated hoop and conical bezel, set with a later certified near colourless rough diamond weighing 0.68 grams. 5.65 grams, 23.88mm overall, 15.99mm internal diameter (approximate size British J, USA 4 3/4, Europe 8.69, Japan 8) (1"). From a deceased Japanese collector, 1970-2015; the rough diamond accompanied by World Gemological Institute Report certificate number WG19624130423; also accompanied by London Diamond Bourse receipt number 0011 dated 1-9-21. Fine condition, small nicks to ring.

18th century AD. A gold D-section annular band with plain exterior, inscription to internal face: 'We rest Content' in cursive script. Cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.92, for a ring of similar style with similar inscription content and script-'With one Consent wee rest Content', dated 17th-18th century AD, donated by Dame Joan Evans; see Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.110, for the BM's example. 4.53 grams, 20.10mm overall, 17.72mm internal diameter (approximate size British O 1/2, USA 7 1/4, Europe 15.61, Japan 15) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition, slightly misshapen.

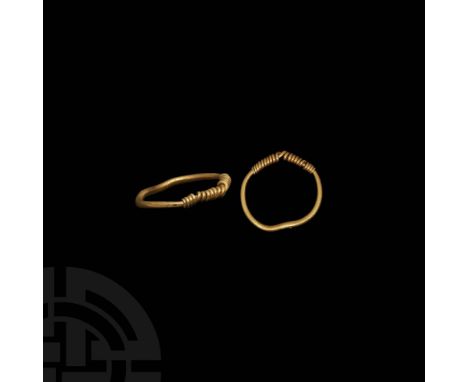

9th-11th century AD. A gold finger ring with round-section hoop, coiled wire sleeves at the shoulders and twisted wire bezel. Cf. The British Museum, museum number 1841,0711.431, for comparable. 3.42 grams, 24.67mm overall, 21.30mm internal diameter (approximate size British R, USA 8 1/2, Europe 18 3/4, Japan 18) (1"). From a central London collection; previously in a European collection formed 1979-1989. [No Reserve] Fair condition, nicks and slightly misshapen. A large wearable size.

18th century AD. A gold D-section annular band with plain outer face, the internal face inscribed 'God alone made us one' in script characters, followed by stamped maker's marks 'MS' in blackletter and 'St' closely stamped in two rectangular cartouches. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.39, for this inscription; cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1239, for a similar ring with this inscription, dated 17th century AD; see The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, IOW-6C0F12, for a gold posy ring also stamped with 'MS' in blackletter script, dated 1613-1733 AD. 4.97 grams, 18.07mm overall, 15.08mm internal diameter (approximate size British H 1/2, USA 4, Europe 6.81, Japan 6) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition.

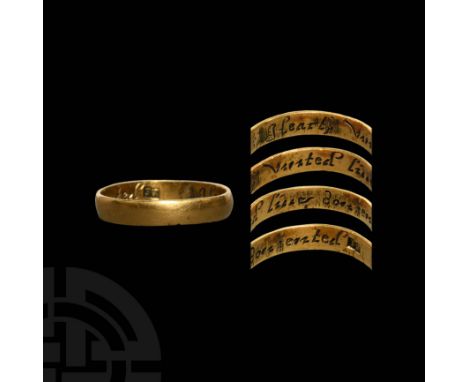

18th century AD. A gold D-section annular band with plain external face, the interior inscribed: 'Hearts united live contented' in script characters, followed by maker's mark 'IV' in rectangular cartouche, probably for John Vickerman. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.47, for this inscription; cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1270, for a similar ring with this inscription, dated 18th century; museum number AF.1269, for a similar ring with this inscription dated 17th-18th century AD; museum number AF.1215, for a gold posy ring with the same maker's mark, dated later 18th century AD; cf. The Fitzwilliam museum, PER.M.324-1923, for a ring with this inscription, undated. 3.58 grams, 21.50mm overall, 18.90mm internal diameter (approximate size British R 1/2, USA 8 3/4, Europe 19.38, Japan 18) (1"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition, a few nicks. A large wearable size.

14th-15th century AD. A gold flat-section annular band, engraved around the exterior with stylised flower-and-sprig ornament alternating with French blackletter inscription: 'ma ioie', meaning 'my joy'. Cf. The V&A Museum, accession number 7125-1860, for a similar ring type. 1.41 grams, 16.79mm overall, 15.69mm internal diameter (approximate size British I 1/2, USA 4 1/2, Europe 8.07, Japan 7) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. The ring is almost certainly of English manufacture and inscribed in the variety of Anglo-French normal for such amatory inscriptions in the late Middle Ages. A 15th century silver thimble bearing the same inscription was sold at Christie's on 31 May 1995, lot 206, while a contemporary ring-brooch in the British Museum reads 'vous estes ma ioy moundeine [you are my earthly joy]'. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’, with posy rings being named thus in the mid 19th century. Prior to this date, there was no specific term for these rings. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition.

5th-3rd century BC. A gold ring with double D-section hoop, expanding at the shoulder to a double bezel with openwork seams, each ornamented with a raised oval cell set with a polished conical garnet cabochon, filigree border and pellets flanked by a Hercules knot. 11.75 grams, 24.60mm overall, 18.90mm internal diameter (approximate size British O, USA 7, Europe 14.98, Japan 14) (1"). Ex collection of a Surrey, UK, gentleman; acquired on the UK art market; previously on the European art market before 2000; this lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by AIAD certificate number no.11025-181467. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] Very fine condition.

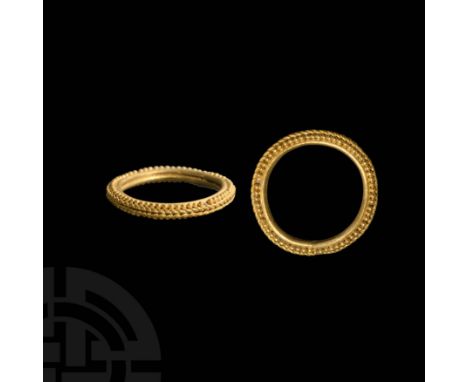

6th-5th century BC. A gold ring composed of a D-section annular hoop ornamented with a medial band of plaited gold wire, a single band of granules above and below. Cf. The British Museum, museum number 1872,0604.25, for a similar hoop. 5.77 grams, 24.92mm overall, 18.58mm internal diameter (approximate size British Q 1/2, USA 8 1/4, Europe 18.12, Japan 17) (1"). Ex important Japanese collection of jewellery, 1970s-2010. Very fine condition, repaired.

10th-12th century AD. A broad gold finger ring with flared rims and median rib, two bands of opposed punchmarks, each a triangle with three pellets inside; several singular annulets and pellets by the outer flanges. 12.48 grams, 26.23mm overall, 22.56mm internal diameter (approximate size British Z+1, USA 12 3/4, Europe 29.99, Japan 28) (1"). From the private collection of a Russian gentleman living in London; acquired from a Chelsea collector in the 2000s; the Chelsea collection having been formed from 1970-1990s; this lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by AIAD certificate number no.11027-181714. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] Fine condition, worn and polished. A very large wearable size.

A Roman hollow gold hardstone intaglio ring,with an oval bevelled banded agate intaglio, engraved with a figure of Virtus Courage on a plinth holding a spear. Roman set in a landscape position, to 'D' section shoulders and shank with a court interior. Head 13.20mm wide, 7.94g.Finger size P-Q range approximately, not roundProvenance: Iconastas, Piccadilly Arcade, St. James's, London, W1Please note that the rings from the Iconastas collection have not been the subject of a metallurgy report, and as such cannot be substantiated in terms of period or purity.Condition report: Intaglio cracked - not all the way through.has been sized in the past. Shallow dents and bruises to the inside of the head.Noticeable scratches and marks. Tested as approximately 20ct gold.

-

563972 item(s)/page

![Dated [16]68 AD. A mourning ring composed of a gold D-section annular band, the external face engraved with a partial stylise](https://cdn.globalauctionplatform.com/3ae71d3e-8613-4112-af58-adc600fd85ab/528a1a12-fe29-4c8c-abd0-adc6010c6612/468x382.jpg)

![Dated 1 January [1]709 AD. A D-section gold annular finger ring with floral and foliate ornament to outer surfaces showing tr](https://cdn.globalauctionplatform.com/3ae71d3e-8613-4112-af58-adc600fd85ab/28ef1b0c-1cd5-4c8d-ac65-adc6010c65a4/468x382.jpg)