We found 375941 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 375941 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

375941 item(s)/page

LUCASFILM - The white poly-cotton t-shirt is marked as a size large and features the Darth Vader in flames artwork printed in colour with the Empire Strikes Back logo situated underneath. Remains unworn. Excellent. Dimensions: 37 cm x 28 cm x 8 cm (14.23'' x 10.77'' x 3.08"). . VAT STATUS: M

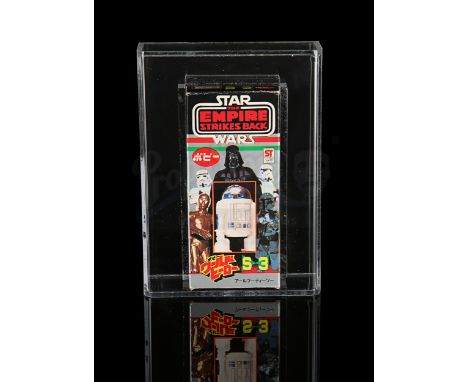

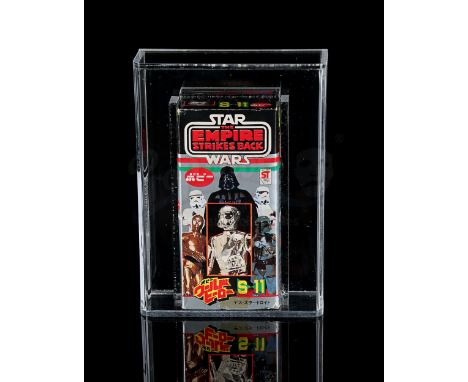

TAKARA - Unique to the Japanese market, this missile-firing R2-D2 was among the earliest Star Wars toys available. Contents complete with unused missiles and stickers not applied. The legs have yellowed over time. Good - Legs have yellowed, stickers not applied. Dimensions: 14 cm x 10 cm x 10 cm (5.38'' x 3.85'' x 3.85"). . VAT STATUS: M

LILI LEDY - Completely unique to the Mexican market, this was the only large-size Tusken Raider produced during the vintage era worldwide. Featuring a unique head sculpting, the outfit consist of a cloth cloak and bandolier straps. No weapon was ever created for this figure. AFA 80+ Excellent. Dimensions: 16 cm x 33 cm x 6 cm (6.15'' x 12.69'' x 2.31"). . VAT STATUS: M

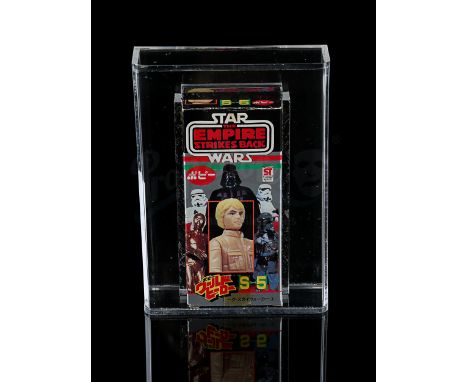

LILI LEDY - Large-size figure complete with body sticker. This design was a near exact copy of the Kenner 3 3/4" action figure but created at nearly double that size as part of the large-size action figure line for the Mexican market. However, unlike the small action figure, the head has no clicker. Excellent. Dimensions: 18 cm x 12 cm x 9 cm (6.92'' x 4.62'' x 3.46"). . VAT STATUS: M

An extremely rare Armand Marseille character smiling boy with intaglio painted eyes size 7, the bisque socket head depicting a young boy with intaglio painted blue eyes with black pupils and white upper eye dots, black line to top eyelid edge, red dot to the inner corner of the eye and centre of nostrils, light brown painted feathered brows, well modelled full cheek with dimples and pleased expression, the closed slightly smiling mouth with a darker red cupid’s bow outline, well defined ears, original blonde mohair wig with curls at nape, composition and wooden ball-jointed body, wearing original coarse linen shirt and modern blue velvet knickerbockers with yellow silk sash, impressed Germany A 7 M —23in. (58.5cm.) high (head perfect, slight kiln dust to side of right face near ear, an extremely tiny firing crack along edge of left top eye lid, body incorrect and slightly too small and wig sparse in places) Notes - this very rare Armand Marseille art character from a series they produced circa 1910. This child’s features are beautifully modelled, probably studied from life. The doll was the child who toy of the vendor’s grandmother who lived in Switzerland at the beginning of the 20th century.

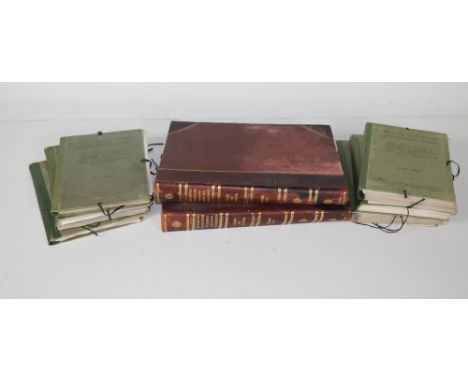

Architectural Interest: Garner (T.) & Strathan (A.) The Domestic Architecture of England during the Tudor Period, 2 vols., folio, L. 1911, profusely illus., hf. mor., gilt lettered spine; together with MaCartney (M.) The Practical Exemplar of Architecture, 6 Series, L. (Architectural Review) n.d., loose, original wrappers, as plates, w.a.f. (8)

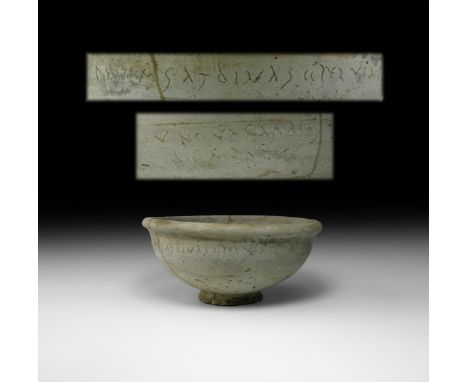

1st-2nd century AD. A ceramic footed bowl with rounded rim, incised line to the equator, cursive inscription which is a simple recipe, mentioning bread and fish to be mixed or dressed with oil and wine, and to be used or served every Tuesday; the bowl was presumably intended and used for the preparation of this recipe, and the mentioning of ingredients makes sense as a reminder or as instruction to domestic staff not entirely familiar with the preparation: 'PANEM SARDINAS OLEI VINI (vacat) VNO(m) VAS AQ(u)ALE(?) / DIE MARTIS' which translates to: 'Bread, sardines, one water(?) bowl of oil (and) wine / on (every?) Tuesday’, or alternatively: 'Bread, sardines, of oil (and) wine; one water(?) bowl on (every?) Tuesday'. For reference to letter forms of Roman cursive in the 1st-2nd century refer to the standard handbook of E. Maunde Thompson, An Introduction to Greek and Latin Palaeography, 1912, tables and samples on p.315-21. 559 grams, 17.5cm (6 3/4"). Property of a Middlesex gentleman; acquired in the 1980s. The M being left out in VNO(m) is a common spelling variant for VNVM and is common in graffiti e.g. from Pompeii, as the final M was already not pronounced anyway at this time, as in modern French and Italian. The reading seems certain but for AQ(u)ALE: the presumed Q looks like no other letter, but is not close to a normal cursive Q either, one must therefore presume that it was mis-written; there is no other Q in the inscription with which to compare it; also, if a Q, one must presume that the next letter V/U was left out (plausible enough, as Q was never used without V/U anyway on the other hand"). On the other hand, I cannot make sense of any other possible reading here. The shape of letter R is very different in SARDINAS compared to MARTIS, yet both readings must count as certain. Latin sarda or (as here) sardina was a small fish pickled or salted, possibly our sardine, but cut probably be used for any small fish thus prepared or conserved. Fine condition, repaired. Extremely rare.

5th-4th century BC. A sheet bronze helmet of Chalcidian type with keeled bowl and carination above the brow, low neck-guard to the rear and raised flange rim extending to the D-shaped ear and eye-recesses; short lozengiform nasal with rim; three-looped hinge fittings to each side for attachment of separate cheek-guards; the outer face tinned for an imposing appearance and to create a glancing surface; mounted on a custom-made stand. See Masson, M. E., Pugachenkova, G. A. Parfi anskie ritony Nisy (Parthian rhyta from Nisa"). Al’bom illiustratsii (Album of illustrations), Moscow, 1956; Beglova, E. A., Antichnoe nasledie Kubani (Ancient heritage of Kuban) III, Moscow, pp.410-422 (in Russian); Dedjulkin A. V., 'Locally Made Protective Equipment of the Population of North-Western Caucasus in the Hellenistic Period', in Stratum Plus, n.3, 2014, pp.169-184; ????????? ?. ?., '????? ??????????? ??????? ?? ????????? ??????' (Sarmatian Age Helmets from Eastern Europe), in Stratum Plus, n.4, 2014, pp.249-284. 2.8 kg, 38cm including stand (15"). Property of a London gentleman; acquired in 2014 from David Aaron Gallery, Berkeley Square, London, W1; previously with Royal-Athena Galleries, New York, US; formerly in a private collection, London, UK; acquired prior to the mid-1950s; accompanied by a copy of an Art Loss Register certificate report number S00142456 and a copies of the relevant Royal-Athena Gallery published catalogue pages. Fine condition.

Late 2nd-early 3rd century AD. A Roman bronze sport helmet of 'Pfrondorf Type' (type F of the Robinson classification of Roman cavalry Sport Helmets, Robinson, 1975, pls.367-375, pp. 126-127), with female features, possibly representing a gorgon (Medusa), comprising a two-part helmet with a back plate, the face piece originally with a removable inner mask; the skull embossed with stylised representations of hair along the sides and collected at the lower centre of the back to a chignon, the centre decorated by a blue enamel stone; on the upper part of the skull a two-headed snake, whose wide body is decorated with scales chiselled on the surface, long neck protruding on the two sides of the skull until the brow; the edge of the skull is decorated by punched triangles and a line representing the crown of the hair around the face; a small flat neck guard; a hinge is fastened through a pin the skull to the mask allowing it to be raised; the T-opening for the face was not always present in this type of helmet. See Robinson, R., The Armour of Imperial Rome, New York, 1975; Garbsch, J., Römische Paraderustüngen, München, 1979; Born, H.,Junkelmann M., Römische Kampf-und Turnierrüstungen, Band VI, Sammlung Axel Guttmann, Mainz,1997; D'Amato R., A.Negin, Decorated Roman Armour, London, 2017; D'Amato R., A.Negin, Roman Heavy Cavalry (1), Cataphractarii and Clibanarii, 1st century BC-5th century AD, Oxford, 2018; this mask helmet belongs to the category of Roman Mask Helmets employed in the sportive games, acting also as military training, of the so called Hyppika Gymnasia described by Arrian of Nicomedia in his Taktika, written down during the age of the Emperor Hadrian (117-138 AD), however, these kind of very simplified masks were often used in battle as well, especially by the heavy cavalry of the catafractarii (D'Amato-Negin, 2018, p.30,36,38-40), the distinguishing features of this type of masked helmet, diffused in the Roman Army since the Late Antonine Age (second half of second century AD) is the removable central area of the mask covering eyes, nose and mouth and the division of the helmet in two parts on the line of the ears; the Pfrondorf specimen (Garbsch,1979, pl.26; Born-Junkelmann,1997, p.50; D'Amato-Negin, 2017, fig.168 a-b), in Stuttgart Museum, which gives the name to the typology, is the most complete and known of such specimens; three parts helmets are known from Danubian sites, like Ostrov (Romania, Robinson, 1975, pls. 370-373; Garbsch, 1979, pl.27), from the German Limes (Oberflorshtadt, Robinson, 1975, fig.129, p.108, D'Amato-Negin, 2017, fig.172c, p.169) and a magnificent specimen, preserved only in the skull, from the collection Axel Guttmann is kept at the Musée d’Art Classique de Mougins (D'Amato-Negin, 2017, fig.172a, p.169); a further splendid specimen, the mask only preserved, is kept in a large private European collection (D'Amato-Negin, 2017, fig.180, p.177"). 2.1 kg total including stand, 27cm (10 1/2"). From an important East Anglian collection of arms and armour; formerly in a Dutch private collection since the 1990s; previously in a Swiss family collection since before 1980; accompanied by a metallurgic analytical report, written by metallurgist Dr. Brian Gilmour of the Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, University of Oxford, report number 144723/HM1364; and an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato; this lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by AIAD certificate number no. 144723-10011. This type of helmet is very rare in such fine condition. Helmets with a facial cut-out have often the female characteristic of Medusa, considering the psychological impact that this creature, with the power to transform men to stone. The apotropaic character of such divinity, inspiring terror on the enemies and confidence to the wearer, was part of the interpenetration of the divine world inside the human world, considered essential for the men who risked their life daily, who needed to feel the protection of the divine beings on the battlefield, or in the travel to the underworld. The main problem of these helmets with face attachment and three-part cutout for eyes, nose and mouth, is the question of the presence of the inner mask. Separate inner masks in bronze are known, some of them silvered (Robinson, 1975, pl.374, p.127, from Stadtpark Mainz), or with slender brows and finely pierced rings in the eye-opening (Robinson, 1975, pl.37,5 p.127, from Weisenberg"). There is no way of ascertaining whether or not our specimen was equipped with an inner mask, though it would appear to be quite possible that it was not, as there are no traces of holes in the point where, in the mask helmets of this typology, the turning pin for the attachment of the mask is usually visible. This suggest that our mask was conceived and used for a more practical use on the battlefield, without excluding its possible employment for the tournaments and the Hyppika Gymnasia. Very fine condition, some restoration. Extremely rare in this condition.

Early 3rd century AD. A sheet bronze mask from a cavalry sports helmet of Heddernheim or Worthing Type with repoussé detailing; the lower edge a flange with ropework detailing, disc to each cheek with whorl pattern, central trefoil void with perforations (breathing holes) to the chin, band of slanting bars above the brow imitating hair; the rim with five groups of attachment holes and lateral tabs to allow the mask to be secured to the outer elements of the helmet, and raised or lowered without removing it. Cf. Garbsch, J. Römische Paraderüstungen, München, 1978 item 53 (Frankfurt-Heddernheim helmet); Robinson, R., The Armour of Imperial Rome, New York, 1975; Born, H.,Junkelmann M., Römische Kampf-und Turnierrüstungen, Band VI, Sammlung Axel Guttmann, Mainz, 1997; D'Amato R., A.Negin, Decorated Roman Armour, London, 2017. 221 grams, 20cm (8"). From an important East Anglian collection of arms and armour; formerly in a Dutch private collection since the 1990s; previously in a Swiss family collection since before 1980; accompanied by a metallurgic analytical report, written by metallurgist Dr. Brian Gilmour of the Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, University of Oxford, report number 144724/HM1361; and an academic report by Roman military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato; this lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by AIAD certificate number no. 144724-10012. The three-part helmets, which form a very important part of the Roman third century helmets, especially of the cavalry ones, have been variously classified by the scholars of the Roman military. Besides the type F of Pfrondorf typology Robinson (1975, pp.126-131) individuated the types G (Hedderneim type) and H (Worthing type"). All three present the characteristic of having a skull and a face mask with a removable central area of the mask covering eyes, nose and mouth. The type G, however, differently from the previous type F, presents a high curved crest on the skull and a front face, imitating that of the Apulian-Corinthian helmets, the type H being of pseudo-Attic shape (Garbsch, 1979, pls.28-29; Born-Junkelmann, 1997, pp.59-63, 106-108; D'Amato-Negin, 2017, pp.106ff., fig.175-181"). The surviving examples of H typology (Worthing helmet, s. D'Amato-Negin, 2017, fig.177 lett.d) suggest the idea that a mask was not always used to protect the face. This could be sometimes achieved by the framed face part of the helmet. In our specimen the missing of the skull does not allow to understand if the face-guard belongs to the Hedderneim or Worthing types: but the missing of fastening elements of the inner mask on the face-guard points towards the second category. According to the classification of M. Kolert, these helmets belong to the III type of mask helmets. The German scholar supported the theory that the main feature of all these helmets was their three-part design and cheek-pieces, or the replacing face part with a cut-out and a mask that was sometimes inserted into it. Most probably this specimen is from a battlefield. The piece is in fine condition. The face-guard is largely complete and comparatively plain. It has an opening in the centre to expose the mouth, nose, and eyes while protecting the brow, cheeks, and chin. The two parts of the helmet were in fact held together either by a hook-and-eye arrangement or a small hinge. Once the two halves of the helmet were in place, they would have been secured to the wearer’s head by lacing at the neck, which was attached to the loops on either side of the neck of the skull. The helmet is relatively scarce in the decoration, but the spiral deserves attention for its connection with the solar cult. The spiral represents the rotary movement of the sun, the spiral is probably the oldest known symbol of human spirituality connected with the sun, together with the swastika or tetragamma. The sun traces a spiral shape every three months in its travels. The connection was also visible in the Celtic art, where the representation of the spiral also follows the path of the sun, describing the movements of the heavenly body over the course of a solar year. The third century was characterised by the great diffusion, among the Roman soldiers, of the solar cult, the Sol Invictus, its symbols often represented on arms and weapons as an apotropaic element of protection. Such cult was diffused especially with the Severan Dynasty, who had connection with the Syria due to the women of the Dynasty, especially Julia Domna, wife of the Emperor Septimius Severus, Julia Mesa, mother of the Emperor Alexander Severus and Julia Soemia, mother of the Emperor Elagabalus. This imperial Syrian family favoured the cult of the Sun, especially in the eastern part of the empire, by building even greater temples in honour of the God Helios, like in the ancient Heliopolis (actual Balbeek) and in Rome. Fine condition, some restoration. Extremely rare.

Late 2nd-early 3rd century AD. A beautiful pair of Roman bronze greaves (ocreae) for cavalry or infantry, providing defence for the shins and knees, each with a separate and articulated knee-guard; the first greave showing a slight pronounced central ridge, the lateral tabs for attachment of the leather strings still visible, both on the greave and knee-guard, the offset edge strips are perforated for attachment of the strap eyelets, while on the upper edge is visible the device for the attachment of the knee joint hinge; on the second greave is an undetected leg splint with slightly more marked central ridge, here the offset edges show the remains of four rivetted tabs to which were attached large rings for the attachment straps, the upper edge with the usual recess for the hinge to attach the knee protection; both greaves show at the lower end a slightly pronounced ankle protection. See Robinson, R., The Armour of Imperial Rome, New York, 1975; Garbsch, J., Römische Paraderustüngen, München, 1979; Kolnìk, T., Rímske a Germ?nske Umenie na Slovensku, Bratislava, 1984; Junkelmann M., Reiter wie Statuen aus Erz, Mainz, 1996; Born H. / Junkelmann, M., Roman Combat and Tournament Armours - Axel Guttmann Collection, vol. 4, Mainz 1997; Bishop M.C. & Coulston J.C.N., Roman military equipment, from the Punic Wars to the Fall of Rome, Oxford, 2006; D’Amato, R., Arms and Armour of the Imperial Roman Soldier, London, 2009; D’Amato-Salimbeti, Bronze Age Greek Warrior, 1600-1100 BC, Oxford, 2011; D'Amato R., Negin A., Decorated Roman Armour, London, 2017. 400 grams total, 44-44.5cm (17 1/2"). From an important English collection; acquired in the 1990s; accompanied by an academic report by Roman military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. Greaves (ocreae) were known as protective equipment as early as in the epics by Homer (Ilias, X, 8, 613), with archaeological finds coming from previous and contemporary Achaean warrior graves (D’Amato-Salimbeti, 2011, pp.36-38"). The use of the greaves inside the Roman army is already attested for the age of the Kings, in 6th century BC, provided for the first class of Hoplites forming the Servian army (Dionysius of Halicarnassus, IV, 16-17; Livy, I,43"). Originally the Romans used mainly Greek and Etruscan pieces which protected the whole lower leg, fashioned around the lower part of it and anatomically fitting the leg. Since the late Consular age were introduced greaves of simpler design, which were made of a bronze plate laced to the front of the leg only, sometimes fitted with a separate knee-guard (D’Amato-Negin, 2017, pp.48-49"). Based on the iconographic sources, centurions in the Roman Imperial army wore decorated greaves (Robinson, 1975, pls.442,445), highly decorated greaves for war and sport games (Hyppika Gymnasia) are recorded in the Roman Archaeology from the second to the early fourth century AD (Garbsch, 1979, pls. 3, 11, 38 and fig. 5, p.11; D’Amato-Negin, 2017, figs.111, 115-124"). Based on the images on the metopae of the memorial in Adamclissi, short, plain unadorned greaves evidently came to be used again by the heavy armoured legionaries (milites gravis armaturae) at the beginning of the second century AD, in order to protect their right leg which was not covered by the shield, or both legs (D’Amato, 2009, p.150, figs.205a, 205c"). It is notable that the greaves of the soldiers were shorter than those of the officers, and that the fastening system was partly different. The knee protection was usually missing: the upper part of the greave was cut horizontally just under the knee and fastened by means of a complicate lacing system at the back of the legs. The Adamclisi specimens have been confirmed by archaeology in later specimens datable to the third century AD and found in Kunzing (Robinson, 1975, pl.510"). The use of greaves for infantry and cavalry continued for the whole second and third century AD on, where pairs of greaves came to be used by heavy infantry, as shown, for example, by the image of a pair of greaves on the tombstone of Severus Acceptus of the Legio VIII Augusta (Bishop-Coulston, 2006, fig.111, p.174), or, for the cavalry, by the recent undecorated specimen found on the Abrittus battlefield (D’Amato-Negin, 2017, fig.125"). Undecorated greaves like our specimens have been found in Eining (early third century AD, München, Archäologische Staatssammlung), Lower Italy (second century AD, Brussels, Musée du Cinquantenaire), Hebron (early second century AD, Jerusalem, National Museum), Oberstimm (second century AD, ingolstadt, Museum) (D’Amato-Negin, 2017, figs.112-113"). Other similar specimens from private collections, like the recently published greaves belonging to the Axel Guttmann Collections (Born - Junkelmann, 1997, S.128, Abb. 82, Taf. XV; Junkelmann, 1996, Q 22"). Most probably our specimens are from a battlefield or from a sacrificial grave of a Germanic warrior. Undecorated bronze or iron examples found elsewhere have a vertical ridge along their whole length in the middle and a more-or-less tight bend, copying the outline of the calf (D’Amato-Negin, 2017, figs.113–114) on both sides, there are two or three bronze rings rivetted to them to insert leather straps to attach them to the leg. Since these greaves have a straight edge at top and bottom, they do not protect the knee or ankle, and due to this we can classify this design as an infantry version. This seems logical, as the infantryman’s knee would have been covered by his fairly large shield and on the basis of images showing similar pieces on infantrymen. A more complex shape, such as, for example, from the greave from Eining, has a curved bottom edge or protruding side parts to protect the ankles, like in our specimens. In addition, in such examples there is a hinged knee part with side loops for attaching a strap. According to J. Garbsch, protection of the knee and ankle proves that it is a cavalry version. This should be not considered an absolute rule, because iconography shows also the employment of full protective greaves, fitted with knee guards, also from infantry, since the second century AD (stele of the optio Aelius Septimus, from Brigetio, s. Kolnìk, 1984, fig.30"). [2] Fine condition, usage wear with some restoration.

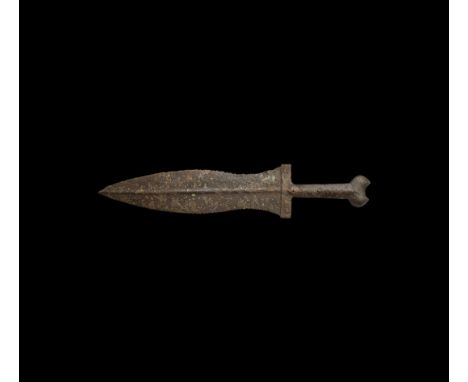

1st-2nd century AD. An iron pugio military dagger with waisted leaf-shaped blade, rounded midrib, rectangular riveted baluster, short grip with crescent pommel. Cf. Feugère, M. Weapons of the Romans, Stroud, 2002, item 173. 324 grams, 25.2cm (10"). From an important English collection; acquired in the 1990s. Fine condition.

1st millennium BC. A hand-forged iron spearhead with lentoid-section tapering two-edged blade, flange wings to the neck, broad socket with fixing holes. See Ehrenberg, M. Bronze Spearheads from Berks, Bucks and Oxon, BAR 34, Oxford, 1977 for discussion of type. 715 grams, 58.4cm (23"). From the family collection of a South East London collector; formerly acquired in the 1960s. The spearhead resembles in shape and overall design the bronze example from Taplow, Buckinghamshire, England, of Middle Bronze Age date (British Museum accession number 1903,0623.1"). The iron construction indicates a date at least 1000 years later than that item, in the late 1st millennium BC. Very fine condition; professionally cleaned, restored and conserved.

12th-late 13th century AD. A long Western European, double-cutting sword with a broad tapering blade, the edges bearing a lot of evidence of its use on the battlefield, both sides of the fullers decorated with inlay: on one side a geometric design of cross-in-ring and scrolled tendrils; on the other side an inlaid brass inscription 'SXS BENEDICAT IUS' with curlicues; the blade has a shallow pointed tip, and to the other face a long lower guard with rounded ends and a broad but short grip, the tang is very stout ending with the usual plain walnut style pommel, substantially D-shaped with slightly curved lower edge. See Oakeshott, E., Sword in hand, London, 2001; Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002; Wagner, T., Worley, J., Holst Blennow, A., Beckholmen, G. Medieval Christian invocation inscriptions on sword blades in Waffen- und Kostümkunde, 2009, 51(1): 11-52; G?osek M., Makiewicz T. Two Encrusted Swords from Zb?szyn, Lubusz Voivodship, in Gladius 27, 2007, pp.137-148; Marek, L., The Blessing of Swords. A new look into inscriptions of the Benedictus, in Acta Militaria Mediaevalia, tom X, 2014, pp.9-20. 1.3 kg, 90cm (35 1/2"). Property of a Suffolk collector; formerly acquired on the European art market in the 1990-2000s; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. This sword has good parallels with a sword published by Peirce, from a private collection (Peirce, 2002, pp.124-125"). Also inscribed, with the usual mark of the workshop, +ULFBERHT+. The current example with religious inscription, a blessing formulation, comparable with the swords showing the inscription BENEDICTUS (Marek, 2014, pp.10ff."). The sword's inscription is most intriguing, and it will help to date the sword in a more precise way. The origin of the inscriptions of this sword is very old. This was a ritual, probably of Germanic origin, in which the father handed down the sword to his grown-up son as a sign that he can defend himself and the tribe. During the Middle Ages the 'sword presentation ceremony', performed by the liege lord or a cleric, put the warrior into service of the former, as a vassal in the first case or as a 'miles Christi ad servitium Iesu Christi' ('soldier of Christ in service of Christ') in the second (Wagner, Worley, Holst Blennow, Beckholmen, 2009, p. 12ff."). Unfortunately, so far it has not been possible to identify such a traditional type of ceremonial dicta latina that was carved on a sword blade. However, quite conversely, the inscriptions (even though sometimes showing a constancy of letters) are extremely variable and appear to be very personal, maybe the individual secret of every sword bearer. It must have been a special dictum so obvious and so self-evident to him, that it was not necessary to spell out its significant meaning. In Germanic tribes runic inscriptions on swords, axes or even pieces of armour were considered to endow the items with magical powers, and it is imaginable that this traditional thinking (after an ambivalent period of transition) was transferred to Christian times. Hence the dicta on the sword blades were probably supposed to invoke God’s holy name and his grace to gain support and protection in battle. Religious rituals or prayers for divine assistance before combat, must have been prevalent, particularly in the age of the crusades throughout the 12th and 13th centuries. In our specimen the inscription is linked with the presence of nomina sacra, typical of specimens from the 11th -13th centuries, where they were written in full length: SXS (SANCTUS) BENEDICAT ('he may bless') IUS meaning 'He (the Holy God) may bless the right one or the law or the right cause'. SXC is the substitution of the original Latin formulation SCS (Sanctus) with SXS, where the Greek letter X (chi) is used at the place of the Latin letter C. IUS can be read the law, the right, or a short formulation for IUSTUM (the right one"). The C was also used in charters as a form 'symbol of Christ', comparable to a chrismon (usually consisting of X and P, but also as capital C), to invoke God’s grace for an act of legal significance. Indeed the use of the X is linked with the initials, in Greek, of the name of Jesus Christ (???????"). A such sword is in the Danish National Museum (inv. nr. D8801, Oakeshott, 2001, pp.48-49, figs.47-48; Peirce, 2002, p.136), with the inscription on the obverse: SCSPETRNNS; and on the reverse BENEDICATNTIUSETMAT. More notably a sword found on the island of Saaremaa (Estonia), dated by A. Anteins to the 13th century, and by D. A. Drboglav to the beginning of this century, where the letters SXS appear. Considering that on another artefact, from Lake Zbaszynskie, the letters ScS appear in place of SXS, this last abbreviation can be read as 's(an)c(tu)S'. However, if we assume that a dot in the inscription on the sword after the letter 'c' is separating the words, we can also develop the inscription as 'S(an)c(tus) S(alvator)' or 'S(an)c(tus) S(anctus)' (G?osek, Makiewicz 2007 p.141"). The dots in the inscription are not always placed according to a rhythm of the words and may even appear in the middle of the letter. Thus a second possible interpretation of the inscription in our sword can be SANCTUS XRISTUS SALVATOR BENEDICAT IUS meaning 'The Holy Saviour Christus may bless the right one or the law or the right cause.' The monogram cross preceding the inscription, is visible on various swords, like the Karlstad sword, in Värmlands Museum (Wagner, Worley, Holst Blennow, Beckholmen, 2009, p.24, figs.12-13), dated to sometime in the 12th or early 13th centuries. Most probably our specimen is from a battlefield, a river find or from a grave. The piece is in excellent condition notwithstanding the corrosion on the blade where signs of battlefield are visible. Many swords of similar type can be classified as German manufacture, and we know that the kind of pommels were in use until the 13th century. The straight guard with thick straight quillons are typical of the style Xa (and XI) of Oakeshott, that, with its double-edged blade, combined the cutting and the cut-and-thrust styles. The fullers, like in this case, are very marked and form not less than two thirds of the length, what makes such sword one of those presenting those elegant proportions which prevail when the blade is almost parallel for some seventy percent of its length before tapering began. Fine condition. A good solid example of a well balanced sword.

Circa 1300 AD. A German great helm in a poor state of preservation, but still visible in its original shape without deformation; composed of five rivetted plates: two forming the top, two the front, and one the back; the top of the helmet is convex; the visual system is divided into two, and on both left and right parts, are distributed the various holes forming the ventilation system. See Demmin A. Die Kriegswaffen in ihren geschichtlichen Entwicklungen von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart. Eine Encyklopädie der Waffenkunde, Gera-Untermhaus, 1891; Müller-Hickler H., 'Über die Funde aus der Burg Tannenberg', ZfHW XIII, in Neue Folge 4, 1934, pp.175-181; Žákovský P., Hošek J., Cisár V., A unique finding of a great helm from the Dale?ín castle in Moravia, in Acta Militaria Medievalia, VIII, 2011, pp.91-125; Gamber O., Geschichte der mittelalterlichen Waffen (Teil 4), in Waffen- und Kostümkunde 37, pp. 1-26; Scalini, M., A bon droyt, Spade di uomini liberi, cavalieri e Santi/Epées d'hommes libres, chevaliers et saints, Milano, 2007. 1.4 kg, 25.6cm (20"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. According to the current knowledge, great helms began to generally appear in the arsenal of western medieval warriors in Western Europe as early as the beginning of the 12th century (Žákovský, Hošek, Cisár, 2011, p.91"). It is not easy to understand which was the medieval word designating such category of helmets. The terms helmvaz and helmhuot, used for instance in the German epic Nibelungenlied, refer probably to large and closed helmets. Some authors therefore associate the origin of great helms with the German lands. The theory can be supported by the fact that most European languages adopted the term for this type of helmets from German helm or great helm in English; heaume in French; elmo in Italian, and yelmo in Spanish (s. Demmin, 1891, pp.492-493; Müller-Hickler 1934, p.179; Gamber, 1995, p.19"). In sources written in Czech, the candidate terms referring to great helms seem to be p?ilbice and the derivative of the German word, helm. The typological evolution of the 14th century in Germany, takes the name of kübelhelm. The general development of great helms was starting in the early 13th century, based on round shapes with straight sides and a flat occipital plate with a distinct edge. They are known, because of the preserved beautiful aquamaniles (Scalini, 2007, pp.132-133, Aquamaniles from Lower Saxony, about 1300 AD; Žákovský, Hošek, Cisár, 2011, p.95, fig.4"). The subsequent development involved larger helms of oval cross-section with a distinctive edge. These helms reached to the shoulders of the wearer and the top was already convex. The helmet here represented should be added to the few survivingv specimens, as it is a good parallel with the great helm from the castle of Tannenberg, dated at the second half of the 15th century. The ventilation system, however, is more similar to the helmet from Dalecin (Žákovský, Hošek, Cisár, 2011, fig.5, p 95, 7, p.97), recently published by Bohemian archaeologists and discovered in 2008 by accident. The top of the helmet is similar to the helmet of Altena (Žákovský, Hošek, Cisár, 2011, p.110, fig.18b"). These great helms of traditional design, and especially those with a convex top, whether of five, four or three plates, are in general believed to have been manufactured in Germany, although any direct evidence is missing (see Boeheim 1890, 29; Pierzak 2005, 31"). Žákovský, Hošek, Cisár believe that the current state of knowledge is not sufficient for determining even the approximate location of their origin. The possibility that some of the known helms were manufactured close to where they were found, cannot be ruled out either. Moreover, it is not likely that the design patterns and details can be used to date the individual specimens at the moment. This is mainly due to the fact that only a small number of great helms have been recorded so far and that most iconographic sources, which could be useful in making the dating estimates, and our knowledge of great helm development more accurate, are rather simplified or the important upper parts of the depicted helms are covered with mantling and jewels. Most probably our specimen is from a castle excavation. The piece is in fair condition and considering the rarity, a high start price can be expected. These helmets are generally thought to be dressed over the chain mail of the hauberk, and supported inside by an internal padding called 'padiglione' in Italian. An example from Tannenberg was unfortunately destroyed during the First World War. The find is quoted, but not illustrated by Demmin (1869, p.276, n.54) who states 'Deutsche Kesselhaube vom Ende des 13. Jahrhunderts, unter dem Schutte des im 14. Jahrhundert eingeäscherten Schlosses Tannenburg gefunden, von welchem Hefner v. Alteneck eine Abbildung herausgegeben hat' meaning: 'German great helm of late 13th century, found under the rubble of the 14th century cremated castle Tannenburg, of which Hefner Von Altenek has an illustration'"). For the weight and the encumbrance of such big helmets were worn only in the imminence of the battle, leaving it, when not in use, suspended by a breast chain fixed on the front but hanging behind the shoulders. In the Tannenberg specimen there is still a small cross-shaped opening on the left side of the frontal part of the helmet, used to allow the passage of a small attachment for the chain which fastened the helmet to the breast part of the armour. The main elements of the knight's protection were helmet, shield and armour, and when the helmet was not necessary and limited the view, was put away. Sometimes, as visible on the splendid Manesse Codex, the helmets were surmounted by a decorative plume or crest, made of organic material like parchment, cuir bouilli, papier-mache, wood or copper sheet. Fair condition. Extremely rare.

Circa 1340 AD. A Western medieval cervelliere's or early bascinet skull in iron, probably Italian, the dome bowl following the shape of the skull, narrower on the front and wider at the occipital bone; the protection of the area is wider than in the usual cervelliere, and all around the rim of the helmet the fastening holes to the inner felt or leather lining, or the sewing to a textile cap, are visible. See Boccia G.L., Rossi F., Morin M., Armi e Armature Lombarde, Milano, 1980; Nicolle, D., Italian Medieval Armies, 1300-1500, London, 1983; Vignola, M., I reperti metallici del castello superiore di Attimis, in Quaderni Friulani,di Archeologia, XIII, 2003, pp.63-81; Scalini, M., A bon droyt, Spade di uomini liberi, cavalieri e Santi/Epées d'hommes libres, chevaliers et saints, Milano, 2007. 881 grams, 22cm (8 1/2"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. The cervelliere was a very common skull protection since the 13th century Italy, made of metal and shaped like a simple skull. It (from Latin cervellerium, cerebrarium, cerebrerium or cerebotarium) was a helmet basic typology developed in Middle Ages. It was made of a single piece of cup-shaped metal covering the top of the skull and could be worn over or under the hauberk and other typologies of heavier helmets. Over time, the cervelliere experienced several evolutions. Many helmets became increasingly pointed and the back of the skull cap elongated to cover the neck, thus developing into the bascinet. The skull protection of our specimen has parallels with the helmets worn by the warriors represented in the killing of the innocents painted in the Church of Saint'Abbondio, Como, dated at 1340 AD (Boccia, Rossi, Morin, fig.10 pp.30-31), which Boccia correctly classified like cervelliere. This specimen is therefore still a cervelliere, or eventually an early form of bascinet of which the cervelliere was the ancestor, although this specimen begins the transformation of the simple skull in the wider bowl that, fitted with a peak, will give origin to the bascinet. Its conformation distinguishes it from the various similar head protections classified as bascinet in the 15th century. The statement that we are still dealing with a cervelliere is based on the morphological data of the object. The shape, above all, is markedly hemispherical, tightening towards the front and falling slightly on the nape. A similar skull is visible on the cerviellere found in the castle of Attimis (Italy, Trentino Alto-Adige), recently published by Vignola (Vignola, 2003, pp.66 ff."). Differently from the usual cervelliere, the bowl shows side protections, and the sides are protecting also the ears, which is not the characteristic of the usual cervelliere. The type then turned out to define in anatomical way and adherent to the skull. Another characteristic trend is the series of holes visible all along the lower edge, from front to the neck. Correctly Vignola suggested, by analysing the specimen of Attimis, that such parallel holes were destined to receive the sewing, to fasten the helmet with a falsata (padded or quilted headgear"). The presence of similar holes in the other helmets of the same category was absolutely fundamental to allow a similar helmet to be worn, as well as to absorb the trauma of a stroke directed towards the plain surface of the cervelliere skull. The falsata had probability the possibility to be fitted with stripes for the protection of the nape, and of thongs to fasten the helmet under chin, too. Moreover, a cap was sometimes worn over the helmet, forming an external textile headgear prolonged over the ears (Nicolle, 1983, pl.B2), often visible in the iconography of the period and considered like a civilian cap by many art historians not particularly skilled in the military equipment study. Most probably our specimen is from a battlefield or a river find. The piece is in good condition and considering the rarity a high start price is expected. Under the profile of the chronology such protections for the head had a long life, from 13th until 16th century, however, conforming with the date proposed by Vignola for the piece of Attimis, the specific morphology of the helmet found precise elements of comparison with the 14th century iconography. By looking at the helmet from the sides, it shows a typical gleaning towards the lower edge, raising to the brow part. This is visible on many cervelliere and bascinets of the 14th century, on the prototypes visible in the so-called biadaiolo (code of the mid-14th century) of the Medicean Laurentian Library in Florence, in the already quoted frescoes of Saint Abbondius and even in some cervelliere represented in the Manesse Code. The ancient sources call such type of objects bascinet, having the shape of a basin or basin without lip, although the shape of the helmet that is modernly designated with this name, has a rather ogival shape as for the head gears of the second half of the fourteenth century. Cervelliere or early bascinets like our specimen, may be dated to the first half of the 14th century, but the formal adherence to the progression of the skull makes it difficult to secure a chronological staggering. However, an artifact examined by Scalini, datable to 1330, from Perugia, shows protective side parts like this specimen, which descend to protect the ears, and allowed also a more comfortable overlap to the knitted shirt. This specimen was used to draw water from a well, until that is was not recognised for its importance. (Scalini, 2007, pp.106-107"). Anecdotally, medieval literature credits the invention of the cervellière to astrologer Michael Scot (Michele Scoto) in 1223. This history is not seriously entertained by most scholars, but in the Chronicon Nonantulanum is recorded that the astrologer devised the iron-plate cap shortly before his own predicted death, which he still inevitably met when a stone weighing two ounces fell on his protected head. Fine condition. Extremely rare.

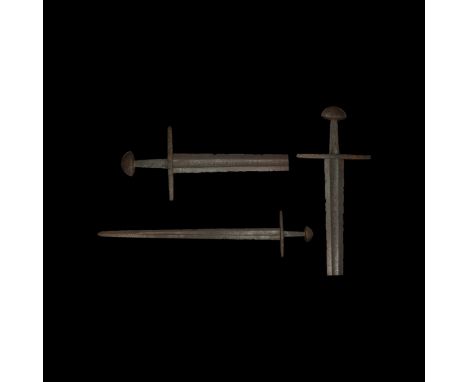

10th - mid 11th century AD. An iron sword with narrow two-edged blade, gently tapering profile with shallow tip, no appreciable fuller, parallel-sided lower guard, short tang and 'tea-cosy' pommel, tiny and yet more precisely formed, being of 'tea-cosy' type transitional to a 'brazil nut' style pommel; the acutely tapered line of the blade makes the blade very elegant, although the fuller, probably existing ab origo, is practically no more visible; the pommel is in excellent state of preservation with some small areas of light pitting; the hilt is plain, carrying no form of decoration; the cross-guard is simply a gently tapering bar of iron, crudely pierced to take the long and robust tang; battle signs visible on the sides, however the cutting ends remain well defined, especially towards the proximal end of the blade, all the components, considered as a whole, create an effect of harmony, balance and quality. See Oakeshott, E., The Sword in the Age of the Chivalry, London,1964 (1994); Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002; cf. Oakeshott, E. Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991, item X9 (Glasgow Museum"). 891 grams, 91.5cm (36"). From the family collection of a South East London collector; formerly acquired in the 1960s; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato.This sword was produced in the workshops of the Holy Roman Empire, with good parallels with various sword published by Peirce (2002, cat. NM2033.1, pp.122-123; NM 11840, pp.132-133"). Especially the sword from Vammala (Finland), in the Suomen Kansallismuseo in Helsinki, shows a great similarity with our model. This latter is however inscribed, like the majority of swords of this category, unlike the current example. The type Xa was in use for a much longer period than the Type XI cavalry swords, whilst the thinner fuller may at first glance appear insignificant - in reality, it marked a serious departure point from the Viking era swords, and were used by late period Vikings, Normans, Anglo-Saxons, Crusaders and Templars, before eventually falling out of favour in the 14th century, when this type of swords began to be quite ineffective against the increasing use of plate armour on the battlefield. On the Bayeux tapestry, there is a depiction of William the Conqueror with a sword of type Xa having a 'tea cosy' pommel, sign of the great diffusion of such kind of sword among the Normans. It is evident that this type was not originally Nordic (in sense of a Viking production), even if it was forged here at home. Besides, it was found in such large quantity, and it was plain in its form. It did exist not only over the whole of Norden but over the whole of Central Europe. It was a common Germanic type in Central and Northern Europe created during the couple of centuries preceding the Crusades, and having a great success until the end of these. Most probably our specimen is from a battlefield, a river or from a grave. The piece is in excellent condition notwithstanding the corrosions of the blade, where signs of battlefield are visible. Originally Oakeshott Type Xa swords were classified by him in the category type XI, but later revised as Oakeshott felt that they deserved their own subcategory, as they were too close to type X to fit within the Type XI category, although the narrower and deeper fuller could not be ignored. However, it was not just the fuller that guided his decision, but the placement of such swords in their historical context, as all existing examples dated from the 11th to the 14th century, while type X started and finished two centuries earlier, from the 9th to the 12th centuries. Like the parent group type X, these were a transitional sword - similar in shape and style to the Viking Age swords that it evolved from - and a stepping stone to the Type XI cavalry swords, which shared the same thin fuller, but had longer, more slender blades better suited to mounted combat. The type Xa presents a broad, flat blade of medium length (average 31) with a fuller running the entire length and fading out an inch or so from the point, which is sometimes acute but more often rounded. The fuller is generally very wide and shallow, but in some cases may be narrower (about 1/3 of the blade's width) and more clearly defined; a short grip, of the same average length (3¾) as the Viking swords. The tang is usually very flat and broad, tapering sharply towards the pommel. The sturdy massive tang provided tremendous strength to the hilt of these long double weapons. The cross - generally of square section, about 7 to 8long, tapering towards the tips, in rare cases curved - is narrower and longer than the more usual Viking kind—though the Vikings used it, calling it 'Gaddhjalt' (spike-hilt) because of its spike-like shape. The pommel is commonly of one of the Brazil-nut forms, but may be of disc form like in this case. The sword appears in two variants, of which the one here presented is the most later and most common. The older variant has a taller and slimmer pommel, while the cross-guard is thicker in profile and slightly curved. The later and more common of the two variants has a lower and thicker pommel and a less thick but longer cross, which can reach even 18 cm of length. The cross-section of the hilt is here evenly wide, with rounded ends, and not cut sharply across, which is otherwise usual with type M. The first group has upper hilts that can reach a length of 7.8 cm. and a height of 5.1 cm. The second group has pommels with a length between 5.0cm and 6.5cm, the height is from 2.7cm - 3.5cm. The lower guard varies in length between 10.7cm to an entire 17.7cm. The height in the first group is up to 2.0cm and in the second group from 0.7cm to 1.4cm. I know 49 specimens of this type. Of those, the later variant is decidedly the most usual. At the time of the Petersen's book in 1919, of the first group there were namely only nine specimens, and 40 specimens of the second group. Of 47 blades identified by Oakeshott, 45 were double-edged and only two single-edged, both from the pronounced 'single-edged' Vestland. Fine condition.

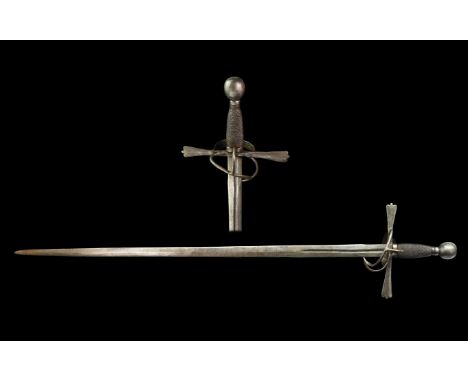

Circa 1500-1540 AD. A 'hand and a half' or 'Bastard' sword, with ring guard, double-edged broad blade, lenticular in section, with single short shallow fuller, running up the first third of its length; the hilt is complex with spherical pommel (style G), the grip is elegantly wrapped with a later iron wire, the cross-guard (style 5) is broad towards the edges, where the iron quillons are ending with three small notches; the handle with a side guard together with the knuckle bow, showing two additional rings on the lower part of the hilt, bowing towards the flat undecorated blade. See Schneider, H., Waffen in Schweizerischen Landesmuseum, GriffWaffen I, Zurich,1980; Talhoffer, H., Medieval Combat: a Fifteenth-Century Illustrated Manual of Swordfighting and Close-Quarter Combat, by Rector, M. (ed."). London, 2000; Oakeshott, E., Sword in hand, London, 2001; Scalini, M., A bon droyt, spade di uomini liberi, cavalieri e santi, Milano, 2007. 1.3 kg, 1.05m (41 1/4"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; believed originally from Liege, Belgium; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. By the second quarter of the 16th century, the long sword had become the 'Bastard' or 'hand and half sword', of which there are many beautiful surviving examples in excellent condition (Oakeshott, 2001, pp.137ff., figs.123-126), like the one here illustrated. The evolution of great and arming swords brought to the transformation of it in the Renaissance rapiers. The samples published by Oakeshott and kept in private collections, show how the developed hilt of the arming sword, which eventually become a rapier, was paralleled in the big 'bastard' swords. Held either in one or both hands, and also known as a ‘bastard’ sword, as its grip was not as long as a traditional two-handed sword, it can be dated to around 1500-1540 based on the decoration of its hilt. The three-notch ends of the crossbars (quillons) are quite flimsy while the finely spherical pommel recalls the swirling lobes that decorated contemporary flagons and candlestick stems. This appearance demonstrates a move away from the brutal simplicity of the medieval sword. The term 'bastard sword' was not, as supported by some scholars, a modern term, but already widely spread in the first half of 16th century. As a military weapon, it was kept in use by the Swiss for almost a century, with very few variations in shape, because it adhered perfectly to the organisational logic of the cantonal troops. So much so, that hundreds of specimens of this type are known, obviously with variations and best represented in the Swiss museums, especially in Zurich (Schneider, 1980, nn. 183-186, 190-195, 198, pp. 129-132, 134-136,138"). Many of them having complex hilts. This interesting piece belongs to the early period of diffusion of rapier in England. With all probability from a battlefield, a castle or a military site. The hilt and spatulate quillons and semi-basket guard for the knuckles is characteristically middle of the 16th century German. It was a long-term employed form, based on the shape of the swords used from horseback, hybridizing them with those of two-handed swords, thus defining an infantryman's sword, very effective against horsemen and pikemen. Its use, predominantly Germanic, involved training and a particular way of shielding, with guard positions, parades and lunges, all different from those of civilian side arms (Scalini, 2007, p.244"). Swords like this were among the most versatile weapons of the battlefield. It could be used one-handed on horseback, two-handed on foot; different techniques were used against armoured and unarmoured opponents; and the sword could even be turned around to deliver a powerful blow with the hilt. Mastery of the difficult physical skills of battle, was one of the chief attributes of the aristocrat. The art of combat was an essential part of a nobleman's education. Sigund Ringeck, a 15th-century fencing master, claimed knights should 'skilfully wield spear, sword, and dagger in a manly way.' These swords, gripped in both hands, were a potent weapon against armour before the development of firearms, but also continued to be used for long time after the diffusion of the guns and arquebuses on the European battlefield of XVI century. To fully appreciate the sword’s meaning for Ringeck as a sixteenth-century gentleman, it is important to understand its double role as both offensive weapon and costume accessory. As costume jewellery the decorative sword hilt flourished fully between 1580 and 1620. However, the seeds were sown long before. This ‘hand-and-a-half’ sword for use in foot combat carries an early sign of this development. No part of a medieval sword was made without both attack and defence in mind. Modern fencing encourages us to see the blade, in fact only the tip of the blade, as the sole attacking element of a sword and the hilt more as a control room and protector. Tight rules prevent the sword hand ever straying from the hilt and the spare hand from getting involved at all. This is a modern mistake. The fifteenth-century Fightbook published by the German fencing master, Hans Talhoffer, illustrates a more pragmatic approach as how two fashionably dressed men settle their differences using undecorated swords with thick diamond-section blades. The blades could be gripped as well as the hilt. The rounded pommels at the end of the grip, and at the ends to the quillons, not only balanced the swing of the sword but acted as hammerheads to deliver the ‘murder-stroke’. As soon as these elements ceased to be functional, they took on the role of adornment. This sword hints at the more decorative hilts produced later in the late 16th and 17th centuries. Swords themselves varied in weight and so did the crossguards. Also there are multiple different crossguards in this category, starting from simple ones with a single sidering or none at all to some complex 'baskets'. Fine condition. Rare.

Circa 1075-1155 AD. An original Viking iron blade of Oakeshott's Type XII, variant 12 (Oakeshott, 1991, p.81), reused with Type XIII, variant 1 hilt, and a T2 pommel (Petersen type Z Viking sword); the double-edged sword has a broad, flat, evenly tapering blade, acutely pointed and magnificently preserved to give an unusually fine balance to its user; the fullers are well defined, deeply cut into the blade to a depth of approximately 1.5mm, divided in three parallel lines extending from below the guard for a little less than half of the blade's length; it is followed by the image of an inlaid beast (a unicorn? a wolf?) chiselled neatly into the surface; the grip is still retaining part of a later leather cover; the style of cross-guard is unusual, and the later pommel is from the T2 category. See Oakeshott, J, R.E., The Archaeology of the weapons, London,1960 (Woodbridge, 1999); Oakeshott, E., The sword in the age of the Chivalry, Woodbridge, 1964 (1994); Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002; Oakeshott, E. Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991; Scalini, M., A bon droit, spade di uomini liberi, cavalieri e santi, Milano, 2007. 1.2 kg, 1.02m (40 1/4"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market via Flicker, inv.1152, classified as Saint Maurice's sword; accompanied by an academic report written by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. This sword, although it can be classified belonging to the XII-XIII groups individuated by Oakeshott (1964 (1994), p.37) resembles, with its singular guard and cross-guard, the famous sword of Jaxa of Miechow, at the Bargello Museum, Florence (Scalini, 2007, pp.111-113, cat.13"). The guard and cross-guard are identical, missing only of the highly decorated elements of the Polish sword. They are a derivation from the typology of the hilts visible in the Petersen group Z, as it is possible to see on the swords from Vesilahti, Finland (Peirce, 2002, p.127, mid 11th century) and Canvick Common, in the Norfolk (Oakeshott, 1991, p.81, dated 1050-1100"). It shows identical hilt with a beautifully-wrought, 11th century Viking sword, that was discovered in 2011 by the archaeologists who were excavating in the Setesdal Valley in Southern Norway. It is clear that the Slavic or Germanic craftsman who made the hilt continued a local tradition derived from the Vikings. Certainly the fact that only few swords existing in the world are showing such particular cross-guard is symptomatic of a local production, and can help to locate the first core of the sword in the Eastern Europe, where also the successive addition could have been made. The cross-guard and the blade are in an incredible state of preservation and we can exclude that they have been ever inside a grave. Maybe, similarly to the sword of Miechow, also this weapon has represented more of a symbol of familiar ownership than a weapon used on the battlefield. Most probably our specimen is a family treasure. The piece is in excellent condition. The sword’s hilt was made in the late 11th or early 12th century, or even at the end of the century, but was with all probably re-adapted to a successive blade presenting the three fullers typical of the Oakeshott XIII.1 typology (Oakeshott, 1991, p.96"). Also the leather covering the grip is probably a further addition from the Renaissance Age (like the leather covering of the grip in the Miechow sword), while the T2 pommel was adapted to the sword possibly in a period comprised between 1360-1420 AD, when the employment of such pommels was very widely spread (Oakeshott, 1994, p.105"). The shape of the sword seems to point also to the typology XIV.7 of the Oakeshott group, and in particular to a sword of the Oakeshott collection (1960, pl.9c; 1991, p.123) dated at 1300 AD. Here the blade tends to be broad, but particularly characteristic are the three deep fullers, punched twice on each side, which seem to be in common use until the XVII century. Interestingly, the small animal punched on the blade seems to be a 12th or 13th century engraving, which will support the idea that the blade could be the original one. The image corresponds near perfectly with the one of the 'Wolf of Passau', i.e. of the image of a 'running wolf' made by the blacksmiths of Passau (Oakeshott, 1960, p.223, fig.105a"). If the blade was made in a Polish or Slavic workshop, its identification with a wolf could be possible, and the linking of the Miechow sword with Jaxa Von Köpenik links also our specimen with the German medieval world. The decoration of the Miechow sword represents an ox or a bull, or even a cow, but it is connected with the heraldry of Jaxa Von Köpenik. It is not impossible therefore to speculate that the engraved running wolf of our sword was in some way chosen because it was the owner's family emblem, or simply because the 13th century blade was done in Passau. During the thirteenth century blade-smiths began again to inlay their products with maker's marks. It is generally possible to distinguish 'trade-marks' from religious symbols. After going out of use for 800 years, it suddenly became popular and was inlaid upon countless sword-blades after perhaps about 1250. It is difficult to draw a line between religious and trademarks: hearts, for instance, whether on their own or within a circle might be either; but where we find a helm, or a shield, or a sword (there is a sword inlaid in the blade of the Type XIII war-sword in the Guildhall Museum, Oakeshott, 1960, pl.7c), or a bull's head (on a sword c. 1300 in Copenhagen), or of course the famous 'Wolf' which is first found on thirteenth-century blades. A mark which can easily be mistaken for the 'Wolf' of Passau is a unicorn; since both wolf and unicorn are only very summarily sketched with a few inlaid strokes, it needs 'the eye of faith' to distinguish an animal at all; the examples of the unicorns which Oakeshott saw on various blades looked exactly the same as the wolves, except that they have a long straight stroke sticking out in front (Oakeshott, 1960, p.223, fig.105b"). Fine condition. Very rare.

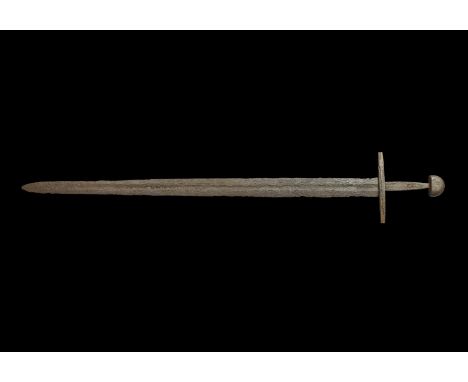

10th-12th century AD. A Viking or Norman Sword with a fine double-edged tapered blade, still retaining well-defined cutting edges and fullers, although the latter being extremely shallow with vague boundaries; traces of employment in fight are visible on the sides and on the point; the blade of the weapon is pattern-welded; the hilt is in excellent condition, comprising of a flat tapering tang and the typical, lower, thicker and shorter pommel of 'tea-cosy' form, with the lower and wider guard reaching a considerable length; overall, the hilt is plain, carrying no form of decoration, and yet, when all of its components are considered as a whole, the effect produced is one of harmony, balance and quality; the sturdy tang provides tremendous strength to the hilt of this long-bladed weapon. See Petersen, J., De Norske Vikingsverd, Oslo, 1919; Oakeshott, E. Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991; Gravett, C., Medieval Norman Knight, 950-1204 AD, London, 1993; Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002. 853 grams, 92cm (36 1/4"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. This sword belongs to the known type X of Petersen (Petersen,1919, pp.158ff) and finds good parallels in various similar Viking age specimens. A very similar sword, with a similar hilt, is the Hagerbakken sword (s. Petersen, 1919, fig.124"). A second parallel can be represented by the sword kept in the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, at the Downing College, Cambridge, found in the River Great Ouse and dating from c. 950-1000, an example is in excellent condition except for the large hole below the cross-guard, which presents iron inlays with inscriptions. Another good parallel is the sword from Vammala (Peirce, 2002, p.132), although the pommel of this latter is tiny than in our sword and yet most precisely formed, being of a 'tea-cosy' type in transition to a 'Brazil nut'. These are types of swords having simpler kind of ornamentation, and they occur in greater numbers, giving on the whole a domestic impression, though it is difficult to fully understand their origin of production, i.e. if local or imported in Viking countries. Contrary to types like B, C and F, these types belong to the late Viking Age, and they also represent a later period than type M, almost simultaneous with type Q, but preceding the last familiar type, type Æ. Our sword belongs to later and most usual of the two variants of type X, with its lower, thicker and shorter pommel and a lower and wider lower guard that at times can reach a considerable length, but that can also be quite short as in type M for example. The cross-section of the hilt is here evenly wide, with rounded ends, and not cut sharply across, which is otherwise usual with type M. The first group has upper hilts [pommels] that can reach a length of 7.8 cm. and a height of 5.1 cm. The second group has pommels with a length between 5.0 cm and 6.5 cm., the height is from 2.7 cm - 3.5 cm. The lower guard varies in length between 10.7 cm to an entire 17.7 cm. The height in the first group is up to 2.0 cm. and in the second group from 0.7 cm to 1.4 cm. At the time when Petersen wrote his huge work he knew not less than 49 specimens of this type, of which this later variant was the most usual. With respect to the actual typological development of the type, it is evident that the taller, slimmer pommels were the early ones, and the small, thick, blunt pommels were the later ones (see for instance the swords of type XI,1-2, Oakeshott,1991, p.54), with the smaller, thicker pommels following the longer lower guards. In particular we shall mention here the sword C 12217 from Sandeherred (Petersen, 1919, fig.129), where the transition to medieval swords has already begun. In this last sword the underside of the already begun to become convex. Blade and handle are very well preserved. Most probably our specimen is coming from a river or a battlefield. The piece is in excellent condition. According to the actual archaeological evidence, type X embraces a very extensive time period. It has been a usual statement given by archaeologists when they speak of this type, that generally it belonged to the end of the Viking Age. One has evidently thought in terms of the medieval forms, with the long straight guards and a more or less rounded pommel. It is however, not that simple, according to Petersen. It is evident that individual swords of the X-type belong among the latest of our swords from the Viking Age, i.e. the 11th and the 12th century. But it is equally evident that the first forms of this type appeared already in the first half of the 10th century. Equally certain, however, is that this type lasted until the very end of the Viking Age. Petersen pointed first one find as mentioned from Nomedal in Hyllestad, and also the over mentioned find c. 1292 from Hagerbakken, V. Toten, where the sword has that long lower guard and represents the best parallel for our sword. These are without doubt at least from the end of the 10th century, most likely even from the beginning of the 11th century. Also another find St. 2589 from Vestly, Lye, Stav. with axe blades of a marked M type, must belong to the last part of the Viking Age. With regards to the additional finds we must believe that these are thought to complete the remaining parts of the 10th century. Based on the available material it is difficult to determine with any more specificity, but we should observe that some swords represented on the Bayeux tapestry and employed by the warriors there represented show such typology (Sword of Harold, Gravett, 1993, p.12"). The swords with tea-cosy pommels were popular among the early Normans and late Vikings (Gravett, 1993, p.5, sample from Wallace collection in British Museum; s. also pp.13-14; pl.A,F"). Fine condition. Very rare.

Circa 1475-1480 AD. A hunting sword, dedicated to the hunt of boar and deer; on the shelled square an inlaid image of a boar (?); the point, shaped as a long facetted leaf with traces of gilding, fitted in the middle with a fuller, and showing a hole which possibly had two metallic wings attached, destined to stop the penetration of the blade inside the body of the hunted beast; the tang still covered by wooden grip, the pommel pear-shaped, while the cross-guard is straight having a central thickness for the passage of the tang. See Scalini, M., ,i>A bon droit, spade di uomini liberi, cavalieri e santi, Milano, 2007; Abbott, P., Armi: storia, tecnologia, evoluzione dalla preistoria a oggi, Milano, 2007. 1.5 kg,1.22m (48"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; believed originally from Liege, Belgium; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. This hunting sword is a good parallel to the famous hunting sword of King Renate d'Anjou (Scalini, 2007, p.206, cat.48), also with inlaid blade with scenes of hunters playing the horn, and various animals. Some parallel is visible also with a hunting boar sword, of Germanic origin, with triangular blade and flamed tip, fitted originally with a leather grip hilt. This kind of swords were held with a hand and half, acting as a hunting spike. The hunting boar sword (German Sauschwert) appeared at the end of the 15th century, and had in contrast to a conventional sword or hunting sword, a four-edged blade, which was flattened and ground at the bottom. At the upper end of this ground blade, there were usually two downwardly bent spikes, which prevented a too deep penetration of the blade into the body of the beast and thus keep the hunter at a safe distance. The handles correspond approximately to the shapes of the usual war swords. Except for the characteristic cutting edge and stopper attached to the blade, this special kind of sword looked similar to Estock. In fact, the boar sword was mainly based on the Estock or tuck, its broad stiffened blade being designed to withstand the power of the charging boar or other large animal. The cutting edge was a double-edged blade, and its shape was often expressed as a 'leaf-shaped' or 'ear-blade-shaped', a part wider than the blade to improve the wounding and killing of the wild boar. The longer body of the sword was not sharpened like the blade of a usual sword: being dedicated to piercing the beast's flesh, it did not require a blade for cutting, also to avoid the risk of wounding of the user. The blade was a hard rod that could withstand the boar's rush, and its cross-section was circular or polygonal, like in our specimen. Many grips were long enough to allow the weapon to be gripped with both hands. From the horse it could be used with one hand, but presence of the stopper and the length of the grip suggest that often it was used with both hands also from horseback. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, the shape of these swords was soon transformed by Italian influence, as the blades became shorter and lighter, finally becoming the hunting knife of the 17th century. Most probably our specimen is from a palace or a private household. The piece is very rare and in excellent condition. Introduced in 14th century, this special type of hunting sword was mainly used for wild boar hunting. By around 1500 it had developed its main characteristic, i.e. the facetted or leaf-shaped spear point, to which was later added, near the end of the blade, the crossbar to prevent the animal running up the length of the blade and so making difficult to retrieve. The crossbar was attached between the cutting edge and the blade to prevent the boar being pierced too deeply by the sword. If the sword stabbed deeply, there was the risk that the wild boar could have stabbed the sword's handler with a fang, and it would have been difficult to remove the sword from the boar's body after. It was necessary to devise measures so that the stopper would not get in the way when placed in the sheath. Unlike a detachable crossbar, some specimens have a rod-shaped stopper that was fixed to the blade with a mechanism that allowed the sword to be fit in the sheath. Specimens of such swords that could be rotated and spread existed, or a fold-able spring loaded with a stopper that automatically expanded when the sword was removed from the sheath. In addition to these rod-shaped stoppers, there were also disk-shaped stoppers, as seen in the hunting spears since the Roman age. While noblemen led the boar-hunt from the horse, using such weapon, the hunters, who belonged to the hunting party, often preferred the so-called winged spear, a spear-like pole-arm fitted with two wings lateral at the blades. Until around 1470, the Burgundian fashion was to hunt, by employing longer, specially shaped swords 'Gjaidschwerter'. Hunting swords from the time of Emperor Maximilian I (1508-1519) have the usual grip of swords to one and a half hand, without German-style fist-guard. Sometimes the pommel had a beak-like shape. The blade was always single-edged with an average length of 85 cm. The hunting party of the German Holy Emperor was composed by a special team, dressed with red coats, low caps and armed with such weapons, deputed to join the Emperor in the boar hunting. Fine condition. Very rare.

Circa 1330 AD. A heavy iron war mace, with hexagonal prismatic head surmounted by an iron button, the faces of the hexagon divided by lines preserving traces of gilding; mounted upon an iron staff with traces of silver, characterised by a ring of entanglement at the top and three concentric circles below. See ??????? ?.?. ???????-????????? ?????????? ?????? ???????? XIV - ?????? XV ??. // ??????????? ????? ? ??????? ? ???????? ????? ??????, ?., 1983; Head, 1984, Armies of the Middle Ages, volume 2, Worthing, 1984; Nicolle, D. Arms and Armour of the Crusading Era, 1050-1350, Islam, Eastern Europe and Asia, London 1999; Bashir, M. (ed.), The Arts of the Muslim Knight, The Furusiyya Art Foundation Collection, Milan, 2008. 1.5 kg, 45.5cm (18"). From an important private family collection of arms and armour; acquired on the European art market in the 1980s, and thence by descent; believed originally from Eastern Europe; accompanied by an academic report by military specialist Dr Raffaele D'Amato. The war mace belongs to the group of the eastern war maces used by the Mongol armies in 13th century. In particular it is an interesting parallel to a mace published by Gorelik (1983, pl.27, n.67), having the same hexagonal prismatic shape, dated at the 13th century AD. It is also the same kind of mace that was brandished by the Il-Kh?nid Persian-Mongol warriors (scene of the battle of Ardashir and Artavan) in the very famous manuscript Demotte Sh?hn?mah, made in ?dharbayj?n in about 1335 AD (Nicolle, 1999, figs.632J"). The mace, perhaps because of its ancient associations, acquired a legendary quality, second only to the swords in the Islamic world, and therefore also of the Ilkhanid Turco-Mongol warlike state, that with the Sultan Ghazan adhered to the Islam in 1295 AD. Amongst Mongols and Turkish warriors, the mace became a symbol of office, and maces, gilded like this one, played a role in ceremonies which significance was a mixture of religious and military elements. From a military point of view, it was an extremely effective weapon in close combat, particularly from horseback against an armoured opponent, where a heavy mace could easily damage even the thickest steel armour and crash heads and helmets at the same time (Bashir, 2008, p.235"). The Ilkhanid Empire was originally part of the Mongol Empire founded by Genghis Khan, its Persian branch created by Hulegu, grandson of Genghis Khan himself. Settled in Persia, the Mongols fostered the growth of cosmopolitan cities with rich courts and wealthy patrons, who encouraged the arts to flourish. At the death of Kublai Khan the Ilkhanid Khanate was de facto independent, until his dissolution in 1335 AD. The core of its army were the powerful armoured cavalrymen, of Mongol, Turkish and Iranian origin, covered with Khuyagh armour, a lamellar or laminated corselet, mainly in iron, sometimes in bronze; they wore hemispherical helmets with reinforced brow, a plume tube or a spike, and mail, lamellar or leather aventail, round shields and offensive weapons like sabres, bow and arrows and naturally war maces (Heath, 1984, pp.114-115"). Most probably our specimen is from an excavation. The piece is very rare and is in excellent condition. The mace is a type of short-arms, a weapon of impact-crushing action, consisting of a wooden or metal handle (rod) and a spherical pommel (head), which can be smooth or studded with spikes. The mace is one of the oldest types of edged weapons, a direct heir to the club, which began to be used in the Stone Age. It became widespread in the late Middle Ages, which was due to the excellent 'armour-piercing' qualities of this weapon. The mace was great for breaking through heavy armour and helmets. The heads of some maces were huge. Mace has several significant advantages over bladed weapons. Firstly, a mace (like a hammer) never got stuck in enemy armour or shield, which often happened with a sword or a spear. With the help of maces, it was possible to completely deprive the enemy of the shield, inflicting several strong blows on it. In this case, either the shield broke, or its owner received a fracture of the limb. You can also add that the blows of the mace almost never slide off. Secondly, you can learn to use a mace much faster than a sword. In addition, these weapons were relatively cheap and almost 'unkillable'. The mace has a significant advantage in comparison with the war hammer: the enemy can be beaten with either side of the weapon. The mace was an essential weapon according the Islamic Fur?s?yah during close combat, and some military treatises are devoted to this weapon (for example, the 'Kit?b Ma?rifat La?b al-Dabb?s f? Awq?t al-?ur?b wa-al-?ir?? ?alá-al-Khayl,' held in Paris, BNF MS Ar. 2830 and BNF MS Ar. 6604; Istanbul, Ayasofya MS 3186; on the fur?s?yah treatises dealing with the art of the mace, see also al-Sarraf, 'Mamluk Fur?s?yah Literature and Its Antecedents'"). The most common name for the club/mace was the Persian 'gurz' and its derivatives: garz, horz and gargaz. The written sources describe four methods of conducting battle: throwing at an enemy from a long distance: close combat at a distance proportioned to the length of the club; rotation of the mace when a warrior was surrounded by enemies; defeating the enemy in front of you. The maces or clubs with huge heads and relatively short poles were suitable for throwing. Our mace belongs to a simplified form of maces, a sort of cube-shaped tops with six cut corners transforming it in hexagon (type II"). All the specimens are in iron and date back to the 12th–14th centuries. A very widespread category of finds is made up of type II maces, mainly found in the excavations of the Southern Russian cities that were destroyed during the Tatar-Mongol invasion. They were also found in Novgorod, Moscow, and in the peasant Kostroma barrows. Usually, maces were considered to belong to the nobility, but the simpler specimens probably were widely available as weapons for ordinary soldiers, citizens and peasants. This is also supported by the simplicity and sometimes carelessness in the decoration of the maces themselves. Fine condition.

2nd century BC-1st century AD. A bronze strap-distributor formed as a wheel with three spokes, enamel-filled cell to the hub. See Green, M. The Wheel as a Cult-Symbol in the Romano-Celtic World, Brussels, 1984. 16.3 grams, 31mm (1 1/4"). Found near Chelmsford, Essex, UK, in the 1980s; collection number 054-A0001. Fine condition.