We found 172550 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 172550 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

172550 item(s)/page

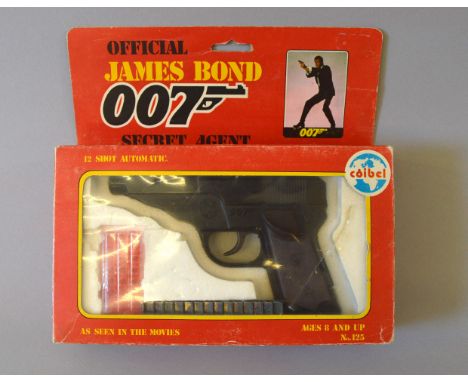

The Yeovil Collection, James Bond 007. Three Coibel (Spain) Official James Bond items: Secret Agent 12 Shot Automatic Pistol, 1985, includes cap pistol and caps, appears VG but floppy trigger in G box, tear to cellophane window, cuts to base, scuffs to edges; Secret Agent Complete Spy Set No. 186, c.1985, scarce, set includes 45 automatic, shoulder holster, silencer, exploding pen, exploding coin, exploding spoon, hide away gun, ankle holsters, James Bond emblem, caps, ID wallet, instructions, E and still sealed but some discolouration from handle of gun that has transferred to shrink wrap, contained in VG box with some scuffs and creases, mainly to edges; Complete Spy Set including shoulder holster, silencer, exploding pen, ID waller, 007 emblem, caps, overall VG in VG box missing cellophane window. (3)

British Coins, George III, pattern halfpenny, in bronzed copper, undated, toothed border, narrow rim, laur. bust r., small eagle’s head below, rev. nude Britannia seated, pointing l., her l. arm resting on shield, paddle behind (P.994 [Extremely Rare]), certified and graded by NGC as Proof 66 Brown, a superlative example of this early pattern for the coming Soho Mint coinage, its surfaces smooth as silk and the colour of fine mahogany, one of the finest known *ex Cheshire collection While the obverse image of King George is familiar and appears, with minute variations, on a number of patterns and proof coppers, it is the reverse of the presently offered pattern coin that compels study and appreciation. In fact, this beautiful coin is almost an illustration, in and of itself, of the achievements of both the Soho Mint and the later die-sinker who ‘rescued’ Soho’s dies, re-struck them, and thereby made coins available for collectors who otherwise would never lay eyes on such items, nor understand their history. All numismatists owe Taylor a huge debt in this regard. We can all study the progression of dies as related by Peck, but why does a regal coin feature on one side an exquisite, heavily frosted portrait of King George, and on the other side an ‘unfinished’ and therefore nude portrayal of the emblem of the land? Crowther tells us what probably happened: ‘The figure of Britannia on the halfpennies by Droz is very graceful. To ensure the agreement of his work with the rules of anatomy, Droz first engraved a nude figure, and afterwards added the drapery. . . . All the halfpennies with the nude reverse were struck by Mr. Taylor’ (pp.43-44). Further, he explains that among the scrap bought by Taylor at the Mint sale in 1848 ‘were found several dies for halfpennies by Droz, and other patterns. A few of these dies had never been used, nor even hardened’. Taylor took these dies, hardened them, paired various ones, burnished them to rid them of rust, and struck small quantities, then destroyed some of the dies. Other dies survived and passed into collections in the late 19th century, but were never used again. Even Crowther, in 1886, says no one knows how many were made, but evidently precious few. All of Taylor’s re-striking activity occurred between 1862 and 1880. He did not evidently set out to deceive collectors. His output of medals was prodigious, as a talented engraver and die-sinker. In the 1850s he was responsible for such creations as the Port Philip gold coins, copper patterns for the Republic of Liberia, and numerous Australian merchants’ tokens, or store cards. His plan was to mint coins on contract as a serious businessman, much as Boulton had done earlier, but his dreams were ruined just a few years later when the price of gold made his ideas difficult to implement. In 1857, his coining press was sold. His passion for coining was not dead, though, and he seems to have wandered into re-striking many of the Soho dies obtained at that sale in 1848. Peck’s cataloguing of all his issues gave credence to his work, and enumerated all known examples for collectors to consider and seek to obtain. Clearly, then, even though this is a restrike, it is a sample of what was a 1790-era trial piece, albeit by a man who did not himself create or engrave either of the dies. What he did was leave for us a testimonial, or memorial, to the artistic accomplishments of earlier artists.

British Coins, Victoria, proof five pounds, 1839, ‘Una and the Lion’, lettered edge, young head l., 9 leaves to rear fillet, rev. DIRIGE legend, crowned figure of the queen as Una stg. l., holding orb and sceptre, lion behind, date below (S.3851; W&R.279), certified and graded by NGC as Proof 62+ Ultra Cameo, of a pleasing yellow-gold colour This is the type issued in the proof set and of the variety with delicately-raised decorations on the fillets in the queen’s hair and DIRIGE in the reverse legend, the entire legend translating into English as ‘May God Direct My Steps’ (Psalm 118:133). The largest gold proof coin from the Coronation set of this year. A classic of the Victorian Age in both style and sentiment, and one of master engraver William Wyon’s masterpieces.

British Coins, Victoria, proof half sovereign, 1839, plain edge, young head l., rev. crowned garnished shield of arms, struck en médaille (S.3859; W&R.344), certified and graded by NGC as Proof 64 Ultra Cameo Mintage figures for the 1839 proofs have long been argued about, 300 original sets being accepted by many numismatists as approximately accurate, but it is worth noting that the £5 Una and the Lion piece was struck by the Royal Mint on demand from collectors through some five decades, up until about 1886, with varying minute details, including edge styles, being telltale indications of whether they were minted in 1839 or later. The same does not seem to be true of the other denominations, although both the sovereign and the half-sovereign are known with either plain or reeded edging, and in both types of die-orientation. The ‘coin rotation’ version was most likely the piece placed in the 1839 sets. The ‘medal rotation’, or en médaille, die orientation, on the other hand, possibly indicates special pieces which may have been presentation items, made during or close to 1839. Such pieces exist for both the sovereign and the half-sovereign. Most collectors, however, seek this coin as a representation of the special proof striking of the charming, early portrait of the queen.

British Coins, Victoria, pattern crown, 1837, in gold, by Bonomi, plain edge with tiny incuse capital T (probably for ‘Thomas’) and, on opposite side of edge, tiny incuse number 4, sunken designs both sides, VICTORIA REG DEI GRATIA incuse, Greek-style portrait of the young queen l., the date 1837, also incuse, split into two digits on either side of truncation, rev. BRITT MINERVA / VICTRIX FID DEF incuse, split vertically in the field, full-length helmeted Britannia in flowing gown and holding body-length trident r., extended right hand supporting classic Victory image, Royal shield partially obscured but glowing behind lower gown, on each rim a border of tiny stars (W&R.364 [R5]; ESC.320A [R5, 6 struck]; Bull 2613, ‘weight of 5 sovereigns’; L&S.14.2, 22-ct gold), certified and graded by NGC as Mint State 66, virtually as struck with toned, frosted surfaces *ex Glendining, 30 April 1972, lot 379 This is the actual piece illustrated in Wilson & Rasmussen. This intriguing, large gold coin has mystified many collectors since it first appeared in 1893. Dated 1837 and the size of a silver crown, it occurs in a variety of metals but its style had never been seen by any numismatist over the course of more than five decades since its apparent date of issue, 1837. Sceptical collectors at first rejected it as a fake, and this opinion continued largely unquestioned until the 1960s. Other collectors, finding its unique design appealing, called it a medal and eagerly bought up specimens as they appeared for sale. Research over the intervening years, however, ended the controversy and revealed that it was privately minted but is collectible as a legitimate pattern crown of Queen Victoria. Examples struck in gold, which are exceedingly rare as only 6 were struck, are now viewed as among the most alluring and important of Victorian pattern crowns. In truth, the Bonomi patterns are indeed a web of fact and fiction, and they remain misunderstood by many. The coins bear a Greco-Roman-Egyptian inspired design: on the obverse, a diademed portrait of the young Queen Victoria, her hair coiled into a bun, facing left, clearly resembling an Egyptian princess. She wears a dangling earring and a thin tiara. In 1837, as the date on this coin suggests, Victoria was still a princess for some months before the crown passed to her upon the death of her uncle, King William IV. She was only 18 years old at the time. On the reverse, Britannia appears standing (not seated, as was tradition), presented as the Greco-Roman goddess Minerva holding Victory in her hand. All in all, the emblematic designs are elegant and suggestive of themes which captured the British public’s imagination circa 1837. Despite the visual appeal of the Bonomi crowns, their means of manufacture remained mysterious for decades after their appearance. Derisive criticism of their origin accompanied examples offered at auction until the late 1960s, and occur even today, but the information in Linecar & Stone’s reference, English Proof and Pattern Crown-Size Pieces, published in 1968, essentially ended the controversy. The book cited the research of Capt. Pridmore, who had discovered that the proceedings of the Numismatic Society of London’s meeting of November 16, 1837, had disclosed the origin of this pattern. The discussion at that meeting mainly focused on the incuse method employed in the minting of these pieces, the intention being to seek to lengthen the life of the coinage by holding back obliteration, or wear from use. That was the primary purpose behind the design: to ‘defy injury’ to the coin’s images during use in commerce. No further proof is really required to label this piece a true pattern. The proceedings of that 1837 meeting mention that Joseph Bonomi, gentleman, was a traveller in Egypt, and an antiquary. They state that Bonomi had designed what he called a medallion in ‘incavo-relievo’ style which would ‘maintain’ the queen’s image for a national coinage. Bonomi’s design was described in the proceedings as showing the queen wearing a tiara on which appeared the royal Uraeus of the pharaohs (a sacred serpent, the cobra, their image of supreme power), and that the surrounding stars of the borders represented the Egyptian emblem of the heavens. The idea of encircling so as to protect was an ancient one. The date of 1837 was meant to represent Victoria’s age at her accession. Finally, the proceedings stated that the reverse inscription, or legend as we call it today, combines the name of a celebrated Egyptian queen with that of the British queen, and includes national emblems. The design for this so-called medallion was never submitted to the authorities of the Crown for consideration as a coin, and examples in any metal rarely appeared for sale until the 20th century. So, the question remains: when and where were they made? Pridmore also revealed that, in May 1893, an advertisement appeared in a publication in England called Numismatology which at last provided some facts about the issuance of the now-famous Bonomi crowns. The 1893 advertisement revealed that the die-sinker was none other than Theophilus Pinches, and that in the same year his well-known company produced a number of pieces in aluminum (or ‘white metal’), tin, copper, bronze, silver, and even gold. Back in 1837, when the coin was designed, Joseph Bonomi had sent nothing more than a cast of his proposed crown to the Numismatic Society. He had not struck any examples. On the cast, Britannia is not shown holding the long trident that appears on the struck pieces. The Pinches pieces were engraved using the cast as the model but added the trident, and also changed the original larger, elongated stars of the borders to small, uniform-sized stars. The 1893 advertisement offered the struck silver pieces for 21 shillings apiece, and included information (some of it nothing but imaginative advertising, for the purposes of selling the coins) indicating that the date of manufacture was 1893, and that all were produced under the auspices of J. Rochelle Thomas. From this source, we know that Thomas engaged the Pinches firm to engrave the dies and to strike the pieces, which in their incuse state faithfully carried out the original concept of the inventor, to use Thomas’s own words. The designs were sunk below the surface, a style that had never been used before and in fact was not used again until the early 20th century on two denominations of U.S. gold coins. In his advertisement, Thomas stated that 10 pieces were struck in white metal. He described his own product as being ‘specimen proofs’, although the presently offered coin has been graded as Mint State. Thomas further stated that the total mintage, in all metals, was 196 pieces. Linecar & Stone, as well as Pridmore, believed that additional pieces were made to order shortly after the 1893 advertisement appeared. However, they concluded that the final mintage figures are as follows: 150 in silver, 10 in tin, 10 in bronze, 10 in copper, 10 in aluminum or white metal, and 6 in 22-carat gold (each weighing the equivalent of five sovereigns, all numbered on the edge).

British Coins, Victoria, proof crown, 1847, UNDECIMO, ‘Gothic’ bust l., rev. crowned, cruciform shields (S.3883; ESC.288; Bull 2571), certified and graded by PCGS as Proof 67, a stunningly beautiful and superbly preserved example of this, possibly the most beautifully designed crown minted in England since Thomas Simon’s patterns This is the most-seen variety (the edge style) of this extremely popular Victorian coin. While 8000 were struck in this year, the vast majority of those coins were bought by gentlemen to be carried as pocket pieces. The result is that nearly all of the mintage was mishandled. Many were polished over the years. Not many were actually damaged, but marks, hairlines, scrapes and even cuts are common. It is, in fact, the pristine coin that is rare, and here we have a coin which approaches perfection and is a model of what is often loosely described as ‘pristine’. If you are seeking a Gothic crown that has retained its originality which glistens with mirrorlike reflectivity, and which offers splendid iridescent toning, you need look no further. This is it!

Ancient Coins, Byzantine Coins, Arab-Byzantine, Anonymous, but probably temp. of Mu’awiya bin Abi Sufyan (AH 41-60/661-680 CE), dechristianised imitation gold solidus of Byzantine Emperor Heraclius, standing figures of Heraclius, Heraclius Constantine and Heraclonas, rev. VICTORIA AVGUB, column on four steps with the letters I and A in the left and right fields, in ex. CONOB, (Constantinople) the conventional mint name, wt. 4.23gms. (A.354B; Walker p.18:54 for type, but does not record for letter A; Bernardi 4), about extremely fine and of the highest rarity This, like the other dechristianised solidi, is an enigmatic and challenging coin. The best discussion of this coinage is found in George Miles’ article Earliest Arab Gold Coinage in the American Numismatic Society Museum Notes No 13. In this article, which still has scholarly validity, Miles records four types of dechristianised solidi. The first of the Emperor Phocas, the second of the young Emperor Heraclius with his son Heraclius Constantine, still a boy. The third shows a much older and heavily bearded emperor with a clean shaven Heraclius Constantine. The fourth is the same type as this piece, except that on Miles’ coin the reverse field bears the letters I and B which appear to left and right of the pole on steps. The dumbbell-like object on top of the pole turns it into a crude version of the Tau cross, thus the resulting design is a crude but virtually identical copy of the Byzantine original, but lacks the crossbar seen on the Christian cross. As such it represents a critical break from conventional Byzantine iconography. This coin, a type which is very rarely encountered today, is well struck and one of the best-preserved specimens recorded. The coin itself gives little obvious clue as to its purpose and origins, but in the historical context of what little is known about Byzantine-Arab relations at the time of its striking, the following observations can be made. There were two occasions when Mu’awiya was obliged to pay tribute to the Byzantines. One was in the year 659 CE when the payment supposedly amounted to a thousand nomismata, a slave and a horse every day. The second was in 678 CE when Mu’awiya was forced to agree to a very harsh treaty that obliged him to make an annual payment to the Byzantine emperor of three thousand nomismata, fifty prisoners and fifty horses. At the same time, and during the same reign, Mu’awiya tried to introduce a dechristianised gold coinage for circulation in Syria. It is also recorded that the Byzantine government refused to accept coinage that did not bear a faithful representation of the Christian cross, and the same was also said of its reception by the largely Christian inhabitants of Syria. This rejection by both the Byzantine authorities and the Syrian population would certainly account for the very great rarity of these coins today. But which of the four types of solidi were intended for tribute to the Byzantine and which for local circulation in Syria is unknown, and neither Miles nor any other previous or subsequent authority has questioned how these four types can be differentiated from one another. Neither historical nor local traditions give us any idea as to how this problem can be solved, but the iconography of the coins themselves may suggest an answer. The originals of all four types certainly circulated widely in Syria, which depended on Byzantine gold and copper coinage to support their monetary needs for both large transactions and everyday purchases. The originals of the first three types were undoubtedly well known to the inhabitants of Syria and, with only minor alterations in their design, Mu’awiya could expect them to be accepted in circulation. In its original form the fourth type, with its Christian and imperial iconography, was struck in great quantities by the Byzantines and would have been familiar to the general public. However, one expert has suggested that on this dechristianised piece the three figures have lost their imperial trappings and appear as tribute bearers, such as the three magi bringing their gifts. The present cataloguer agrees with this interpretation. Once the tribute reached Constantinople, these gold coins would have been rejected, melted and re-struck into conventional Byzantine solidi, which would account for their extreme rarity. This hypothesis is reinforced by the two letters I and A, flanking the pole of the reverse, because they could stand for the first tribute payment of the year A. The other example of this piece carries the letters I and B, which would have been the tribute for the year B. In this cataloguer’s opinion Mu’awiya’s treaty obligations to the Byzantines would have taken priority over the issuance of a purely local coinage for his own subjects who had, up to this time, been able to supply their domestic needs through existing coinage stocks. This extremely rare piece satisfies Miles’ observations on the earliest Arab gold coinage and it may be regarded as the precurser of all the later Islamic gold coinage. References: Miles, G: Earliest Arab Gold Coinage in the American Numismatic Society Museum Notes, No 13, 1967; Foss, S: Arab Byzantine Coins: An Introduction with a Catalogue of the Dumbarton Oaks Collection, Harvard University Press 2008

Foreign Coins, Australia, Victoria, Adelaide pound, 1852, type one, central crown above date within beaded circle, a curled dentillated pattern within the beading, legend surrounds the design declaring the issuer as the GOVERNMENT ASSAY OFFICE with a floral stop on each side of ADELAIDE at centre bottom, rev. VALUE ONE POUND in three lines within a circle of beads inside two linear circles, weight and purity declaration occupying the surrounding legend space, the gold’s fineness of 22 CARATS set within a pair of floral stops, and importantly the die cracked to left of ‘D’ at top of legend from the beading to the rim, fine edge milling (KM.1; Fr.1), certified and graded by PCGS as Mint State 61, perfectly centred and sharp in all details, the surfaces displaying numerous small abrasions but, notably, no large marks or damage, extremely rare and the classic rarity of early Australia, finest graded by 3 points by both services The Type 1 variety of this famous coin, of which it is believed that no more than 50 were struck before the famous die-crack on the reverse developed in size until the die was unusable, is both a great rarity and the very first gold coin type struck in Australia. Most known specimens are not without marks because, at the time of their minting, coins were not being saved by collectors; all of the locally made gold coins were much needed for commerce, and both varieties of 1852 Adelaide pounds were soon mixed together and distributed to banks for use. Almost all of them ultimately perished. The continent of Australia remained the domain of scattered indigenous people for centuries until ‘transported’ British convicts, followed by other settlers, began to make a new civilization in the early nineteenth century. The towns, mostly distant from each other, existed because of farming and cattle ranching. Hard monies seen in early Australia were cast-offs, like most of the inhabitants. All this changed in the early 1850s with the discovery of gold near the town of Adelaide; other gold fields were soon discovered, and these over the course of only a few decades would change Australia from being a sleepy outback into a new country of great prosperity. Soon, too, worn-out old foreign coins ceased to be the main currency. Prospectors quickly brought specie to towns near the gold fields but, as was equally true in early California during its gold rush of 1849, nuggets and gold dust were not easily used for money. Commerce was consequently stymied despite the influx of this new source of real wealth. There were two problems to be sorted out. Turning raw gold into usable coinage was no simple affair, nor was it legal for an British colony to produce its own money without first obtaining approval from the British Crown. In 1852 all distant communication was by mail, via sea passage, and it simply was not practical to await legal sanction to coin money in the name of Queen Victoria. The need for gold coins for local use was pressing. Ideally such coins would have the same value as the familiar English sovereigns. So, in November of 1852, the South Australia Legislative Council passed an emergency measure, entitled the Bullion Act. At first the assay office thereby created smelted ore into ingots, but these were no more easily used in commerce than gold dust or nuggets. What to do until approval from London arrived? The Council decided to hire a local die-sinker by the name of Joshua Payne. He produced a pair of dies that created the now-famous Adelaide pound featuring the distinctive legends as well as a declared fineness and weight in gold. The resulting ‘emergency tokens’ looked exactly like coins; they were not elegant but they were of good weight. The issuing authority never intended its golden money to be more than token issues of solid value and must have assumed that their local coins would be recalled and turned into new sovereigns, once approval of the Crown was obtained. But history intervened, and a legendary coin for collectors was born. The local die-sinker had done his job but evidently failed to make the dies of sufficient hardness: after producing just a tiny number of coins, the reverse die failed, cracking at the 12-o’clock position from the rim inward (to the left of ‘DWT’ in the legend). The first die split apart and another die was quickly made, varying slightly from the first - the simple beaded circle with two linear outlines changed to resemble the form used for the obverse - and this time it was correctly hardened and ultimately produced an estimated 25,000 gold pounds. These were all rapidly thrown into commerce, as were the handful minted showing the die-break, of which only 25 to 50 are thought to have been made. Almost all of these coins experienced plenty of use because they were needed for commerce. Nobody at the time noticed that some of the coins were different from the others. No collectors saved coins in 1850s South Australia! The Crown in Britain meanwhile passed warrants to establish an officially sanctioned mint for the colony. In August of 1853, Parliament authorized an official branch of the Royal Mint, and on 14 May 1855 the Sydney Mint opened in a portion of the old Rum Hospital. The first gold sovereigns were struck in Australia on 23 June of the same year, bearing a variant of the Young Head portrait seen on London Mint coins but with a distinctive reverse. Over time the new sovereigns replaced the Adelaide pounds as the money of choice. One of the ironies of the situation then caused the Adelaide pounds to disappear: the mint’s assayers as well as others discovered that the Adelaide ‘tokens’ were actually finer than advertised, more valuable intrinsically than the sovereigns that replaced them. Anyone in possession of an Adelaide pound did not in fact have 20 shillings (one sovereign) of value but rather 21 shillings and 11 pence, the actual value at the time of the gold content of the coins. The result? Almost all Adelaide pounds ended up being melted for the profit in gold this produced. They quickly disappeared. They perished. Every survivor is a miracle of chance. The coin offered here is far from perfect, but clearly it was never abused, and somehow it escaped the fate of almost all of the rest of the mintage. What was born of necessity as an experiment, was then rejected as inferior, then gathered up as being more valuable than it was thought to be, and was ultimately greedily destroyed, ended up becoming more desirable than anyone contemporary with its creation could ever have imagined. As the image at the centre of its obverse suggests, it has become a crown jewel of the coinage of early Australia.

Islamic Coins, Umayyad, temp. Hisham, gold dinar, Ifriqiya 114h, wt. 4.26gms. (A.136C; Bernardi 43Ca; Walker P.54), a metal defect on the obverse at 3 o’clock, otherwise good very fine and of the highest rarity According to Walker’s Catalogue of Muhammadan Coins – Volume I: Arab-Byzantine and Post Reform Umayyad (1956), and Bernardi’s more recent work Arabic Gold Coins Corus I (2010), only one other example of this date is known. This coin was published by Lavoix and is in the Cabinet des Médailles, Paris.

World Coins, Egypt, British Protectorate (1914-1922), silver 20 piastres, 1920H, struck in the name of Sultan Fuad at the Heaton Mint, Birmingham, the Sultan’s titles in bold Arabic script with accession date 1335h below, rev. value, date 1920/1338 in Latin and Arabic numerals, and mint mark H below (KM.328, plate coin), light grey original toning, certified and graded by NGC as Mint State 64 and of the highest rarity This is the piece pictured in Krause & Mischler’s Standard Catalog of World Coins. The 1920H 20 piastres is one of only two examples struck by the Heaton Mint Birmingham. One was submitted to Sultan Fuad for approval and is now housed in the Mint Museum, Abbasiya, on the outskirts of Cairo. The second (this coin) was retained by the Birmingham Mint in their archive until their collection was de-acquisitioned in the mid-1970s. It then passed, via Spink & Son, into the hands of the famous American collector of British Colonial coins, Mr Richard J. Ford of Michigan. The coin returned to London for the sale by Spink & Son of the Ford Collection (Spink Coin Auction 88, lot 411) in October 1991, where the current owner acquired the piece. Finally, it is worth noting that in the book A Numismatic History of the Birmingham Mint by James O’Sweeny there is no reference to this coin. Details of all other 1920 issues are recorded.

World Coins, Egypt, Fuad I, pattern silver 20 piastres, AH 1348/1929CE, struck at the Royal Mint, London, on a small thick flan, military bust l, initials PM (Percy Metcalfe), rev. value and date above central circle, 37mm., wt. 25.98gms. (KM.-), light grey toning, an unpublished coin, extremely fine, of the highest rarity In 1929 King Fuad ordered the minting of new coins and two designs for the 20 piastres were submitted for approval. The first was by the Egyptian designer Hamed Effendi Serri, which continued to show the King in civilian dress. The second, designed by Percy Metcalfe of the Royal Mint in London, portrayed the King in military uniform. King Fuad, an avid collector (a forerunner to his legendary father) chose the latter in order to have more variety in his coinage. It is interesting to note that this pattern was produced on a smaller and thicker flan than the issued coin (ref: Encyclopedia and Catalogue of Egyptian Coins by Eng Magdy Hanafy 2015, cf. p.226, where no illustration of this coin is available.)

World Coins, France, Napoleon I, restored (1815), pattern 5 francs, 1815A, by Droz, laur. head r., rev. value and date within wreath (Maz.568A; KM.Pn21 var.), certified and graded by NGC as Proof 65, a beautiful example of this rare pattern The year of this pattern crown, 1815, was of course a pivotal time for the national coinage: Napoleon’s last pieces of this size, of the style struck from the ‘An’ (‘Year’) era from 1795-1814, were replaced in 1816 by the coinage of Louis XVIII, for whom a number of pattern 5 francs were created. This rare 1815 pattern undoubtedly was intended for Bonaparte’s return from exile on Elba, in February of this year. All his hopes and plans of course ended in June at Waterloo. This coin remains as an indelible memento of Napoleon’s famous 100 Days. Its quality would be difficult to better.

World Coins, India, Republic, pattern or trial bi-metallic 5 rupees, 2004, in copper-nickel with brass or aluminum-bonze centre, lion capitol of Ashoka Pillar with date below, rev. raised hand and denomination (KM.-), authenticated and graded by PCGS as Specimen 62, extremely rare and unpublished in any of the major reference publications No bi-metallic 5 rupee coin has ever been struck for circulation by the Indian mints.

Islamic Coins, Ottoman Empire, Mahmud II, debased silver 50 para, Baghdad 1223/regnal year 13h, toughra within knotted circle, rev. mint name with accession and regnal dates, wt. 4.62gms. (KM.-; Pere-), previously unpublished, good very fine and extremely rare *ex Sultan Collection, part 2, Künker, Germany, 18 June 2012, lot 1758 KM. records an issue of 50 para, dated 1223/13h (KM.A54) and weighing 4.62gms. (as the above coin), but of a different design without the toughra.

Islamic Coins, Ottoman Empire, Mahmud II, billon 40 para (piastre?), Baghdad 1223/regnal year 13, ornamented toughra, rev. mint name with accession and regnal dates, wt. 3.79gms. (KM.53 – plate coin), good very fine and very rare *ex Sultan Collection, part 2, Künker, Germany, 18 June 2012, lot 1759

World Coins, Russia, Nicholas II, End of the House of Romanov, rouble, 1897, St. Petersburg mint, bare head l., rev. crowned double-headed eagle, countermarked 1917 and legend within octagonal stamp, to commemorate the event, host coin fine, counterstamp very fine, rare The counterstamp is usually placed on the coin’s obverse as a statement against Nicholas II.

World Coins, Switzerland, Graubünden, Shooting Festival proof gold 50 francs, 2012, Helvetia bestowing wreath on kneeling man holding rifle, rev. value within wreath, HF900 below (KM.-; Fr.-; Richter 2-448; Häb.87c), certified and graded by NGC as Proof 70 Ultra Cameo Only 6 pieces minted. Only this example graded by NGC and PCGS and this is the highest grade that a coin can achieve.

World Coins, Switzerland, Lucerne, Shooting Festival proof gold 500 francs, 2013, female figure holding wreath over dying lion, rev. value within wreath, HF 999 below (KM.-; Fr.514v; Richter -; Häb.90a), certified and graded by NGC as Proof 70 Ultra Cameo A total of only 9 examples graded this fine by NGC and PCGS - this is the highest grade that a coin can achieve.

World Coins, Switzerland, Lucerne, Shooting Festival proof gold 50 francs, 2013, female figure holding wreath over dying lion, rev. value within wreath, HF 900 below (KM.-; Fr.-; Richter 2-454; Häb.89b), certified and graded by NGC as Proof 70 Ultra Cameo Only 6 pieces minted. Only this example graded by NGC and PCGS and this is the highest grade that a coin can achieve.

British Medals, Sport, Olympic Games, London, 1908, an un-awarded silver medal winner’s medal for the 15 metre yacht race (a race that never took place), by Bertram Mackennal, for Messrs. Vaughton & Sons, two female figures placing a laurel crown on the head of a young victorious athlete, in a divided exergue, OLYMPIC GAMES - London, 1908, rev. St. George slays the dragon before the winged figure of Peace, edge engraved in caps, 15 METRE YACHT-RACE, 33.5mm.; wt. 21.7gms. (BHM.3964; Eimer 1905; Alfen 47; Johnson -, no silver medal in collection), matt surface, some light toning, mint state, extremely rare and believed a unique survivor *ex Baldwin’s vault The Olympic yachting races were scheduled to take place at Ryde in the Isle of Wight, hosted by the Royal Victoria Yacht Club, however the town was to host only the races for the 6-, 7- and 8-metre yachts. There were only two entries for the 12-metre yachts, both British, and since both were based in Scotland, the races were re-scheduled for Hunters Quay and hosted by the Clyde Corinthian Yacht Club. In the build-up to the Games there had been no entries for the 15-metre class and consequently the category was cancelled. In yachting events it was intended to give the winning helmsman and mate gold medals, and silver to the crew; likewise for second place the helmsman and mate would receive silver medals and the crew bronze; whilst for third place all would receive bronze medals. It is recorded that T D McMeekin, the owner of the winning 6-metre yacht, was awarded a gilt-silver medal. See also Mark Jones, The Art of the Medal, London, 1979, p. 383; Deborah Edwards, Bertram Mackennal: The Fifth Balnaves Foundation Sculpture Project, Art Gallery New South Wales (2007), pp 154-163 - Mark Stocker, Athletes, Monarchs and Seahorses: Mackennal’s Coin, Medal and Stamp Designs, illus. p. 154

World Medals, Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha (1769-1805-1849), Wāli of Egypt, Overland Route to India, copper medal, 1840, by A .J. Stothard (London), MEHEMET ALI PACHA, bust three-quarters l., with flowing beard and wearing fez, rev. FROM THE COMMITTEE THE FRIEND OF SCIENCE COMMERCE & ORDER WHO PROTECTED THE SUBJECTS AND PROPERTY OF ADVERSE POWERS AND KEPT OPEN THE OVERLAND ROUTE TO INDIA 1840, in 10 lines above crossed palm leaves, 57.5mm. (Pudd. 842.2; Fearon 696), nearly extremely fine *bt. Baldwin Islamic Coin Auction 14, 8 July 2008 (lot 696). Alfred Joseph Stothard (1793-1864), was the son of the distinguished painter, Thomas Stothard. He was a sculptor and medallist, and was appointed medallist to King George IV, for whom he executed a fine portrait medal. He signs the medal on the border below the bust ‘A. J. STOTHARD MEDAL ENGRAVER BY APPOINTMENT TO HER MAJESTY D. & F.’

World Medals, Ibrahim Pasha (1789-1848), eldest son of Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha, Wāli of Egypt, Visit to Paris Mint, 6 May 1846, copper medal, by Émil Rogat (1799-1852), MEHEMET ALI RÉGÉNÉRATEUR DE L’ÉGYPTE, bust of Muhammad ‘Ali r., to r. in Arabic ‘Muhammad ‘Ali muhyi al-dawla al-Misiriya’ (Muhammad ‘Ali Reviver of the Egyptian State), signed on truncation, E. ROGAT 1840 and alongside in Arabic the same name with date 1356, rev. legend in Arabic, surrounded by wreath of laurel leaves, ‘His Highness Ibrahim Pasha has honoured the Paris Mint by his visit on the 6th of May 1846’, 51.5mm., extremely fine, rare *bt. Baldwin Islamic Coin Auction 4, 8 May 2002 (lot 465). Muhammad Ali Pasha, Governor of Misir (elected 1805), Sudan (which he conquered in 1822-1823) Filistin, Suriye, Hicaz, Mora, Tasoz and Girit. Later he occupied Syria 1831-1840. He is buried in the Alabaster Mosque in the Citadel in Cairo, the same Citadel where he massacred the Mamluks in 1811.

World Medals, Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha (1769-1805-1849), Wāli of Egypt, Foundation of the Stone Bridges Across the Nile in the Delta Region, copper medal, undated (AH.1263 - 1847), unsigned, a closed sluice-gate in the Nile Barrage, rev. inscription in Arabic in seven lines, 44mm. (Nicol 6220), very fine *bt. Baldwin Islamic Coin Auction 4, 8 May 2002 (lot 467, part).

World Medals, Compagnie Universelle du Canal Maritime de Suez, Opening of Suez Canal, silver medal, 1869, by Oscar Roty, seated female figures holds aloft the light of Progress to the standing figure of Industry, beyond, a sketched route of the Suez Canal, rev. legend in centre and around, inscriptions, 42mm. (Divo 606; BM. Acq 1983-1987 p.25, 147), matt surface, extremely fine; Ismael Pasha (1863-1979), Khedive, Opening of Suez Canal, French white metal medal, 1869, bust three-quarters l., rev. panorama of canal, outer Arabic legends both sides, 37mm., integral suspension loop, obverse lacks brightness, very fine (2) *bt. Baldwin Islamic Coin Auction 14, 8 July 2008 (lots 279 & 280) The Compagnie Universelle du Canal Maritime de Suez was formed in 1858. French private investors were the majority of the shareholders, with Egypt also having a significant stake, however, in 1875, a financial crisis forced Isma’il to sell his shares to the British Government for £3,976,582. The company operated the canal until 1956, when it was nationalized by Colonel Nasser.

World Medals, Compagnie Universelle du Canal Maritime de Suez, Opening of Suez Canal, similar silver medals (2), 1869, by Oscar Roty, on thick and thin flans, seated female figure holds aloft the light of Progress to the standing figure of Industry, beyond, a sketched route of the Suez Canal, rev. legend in centre and around, inscriptions, 42mm. (Divo 606; BM. Acq 1983-1987 p.25, 147), matt surface, extremely fine (2) *bt. Baldwin Islamic Coin Auction 4, 8 May 2002 (lot 466); Baldwin Islamic Coin Auction 5, 29 October 2010 (lot 494). See footnote to previous lot 467.

World Medals, Abdul Hamid II (1876-1909), National Exhibition, Alexandria, AH.1311 (1894), copper medal, by O. Schultz, in the name of the Khedive Abbas II Hilmi (1874-1944; Khedive 1892-1914), crown over Arabic cypher, legend in French around, rev. further legends, 40mm., good extremely fine *bt. Baldwin Islamic Coin Auction 4, 8 May 2002 (lot 467, part).

World Medals, Fuad (1868-1936; Sultan 1917, King 1922), International Geographical Conference, Cairo, bronze medal, 1925, by S. E. Vernier, uniformed bust r., wearing fez, rev. Egypt’s Citadel, Royal arms and legends in Arabic below, 72.5mm., extremely fine, scarce *bt. Baldwin Islamic Coin Auction 4, 8 May 2002 (lot 469) The Conference opened on 1 April 1925 at the premises of the Egyptian Geographic Society (founded by Khedive Ismail). The medal’s reverse is signed with a reversed VE monogram and dated 19/24.

World Medals, Fuad (1868-1936; Sultan 1917, King 1922), official visit to Britain, bronze medal, 1927, by Percy Metcalfe and (reverse) Charles L. Doman, uniformed bust of Fuad l., wearing fez, rev. conjoined busts of Britannia and Egyptia in the Art Deco style, legend in five lines in cartouche below, 71mm. (BHM.4211; Eimer 2007), matt surface, good extremely fine *bt. Baldwin Islamic Coin Auction 4, 8 May 2002 (lot 471) The medal was struck by the Royal Mint in 1930. As well as a formal reception at Guildhall in London, on 5 July 1927, King Fuad’s visit included a trip to Horrockses Cotton Mill in Preston, Lancashire and staying with the Hon. Mrs. Margaret Greville at Polsedon Lacey.

World Medals, Fuad (1868-1936; Sultan 1917, King 1922), Official Visit to France, bronze medal, 1927, by S. E. Vernier and (reverse) Falize Frères, uniformed bust r., wearing fez, rev. an obelisk before a radiant Arc de Triomph, an Egyptian lotus to l., rose to r. with olive spray between them, legend in cartouche below, 72mm., matt surface, extremely fine *bt. Baldwin Islamic Coin Auction 4, 8 May 2002 (lot 472) The Maison Falize, mostly known for their jewellery designs, lasted for three generations. Alexis Falize (1811-1898) opened his workshop in 1838; he was succeeded by his son Lucien (1839- 1897), then, in turn, André Falize (1872-1936) who worked with his brothers Jean and Pierre under the name Falize Frères.

World Medals, Fuad (1868-1936; Sultan 1917, King 1922), University of Cairo, Centenary of the Facility of Medicine and International Congress of Tropical Medicine, bronze medal, 1928, by Henri Dropsy (1885-1969), bust r., scrolled Arabic legend, rev. ancient Egyptian figures by two trees, crowned star above, 61mm. (Dropsy, Paris 1964, - ), extremely fine *bt. Baldwin Islamic Coin Auction 4, 8 May 2002 (lot 473, part)

World Medals, Fuad (1868-1936; Sultan 1917, King 1922), Official Visit to Germany, 1929, by S. E. Vernier and (reverse) Max Bezner (1883-c.1953), bronze medal, uniformed bust r., wearing fez, rev. ÄGYPTEN-DEUTSCHLAND, Sphinx with Egyptian and German emblems, before the Brandenburg Gate, 72mm., extremely fine and rare *bt. Baldwin Islamic Coin Auction 4, 26 October 2010 (lot 474)

World Medals, Fuad (1868-1936; Sultan 1917, King 1922), Visit to Tourah, bronze medal, 1933, by Huguenin Frères, industrial scene with three felucca moored alongside the Tourah cement works, rev. legends in French and Arabic around central monogram, 60.5mm., very fine *bt. Baldwin Islamic Coin Auction 4, 8 May 2002 (lot 475, part) The Tourah Portland Cement Company was established in 1927 and started its production in 1929.

World Medals, Kings Farouq and Fuad, l’Institut d’ Égypte, 150th Anniversary, bronze medal, 1948, by Henri Dropsy (1885-1969), conjoined busts of the Kings r., both wearing fezzes, rev. dates of the various forms of the Institute from 1798, ancient Egyptian motif above, Arabic legend below, 58mm. (Dropsy, Paris 1964, 202), very fine *bt. Baldwin Islamic Coin Auction 17, 26 October 2010 (lot 432) The Institut d’Égypte was a learned academy originally formed by Napoleon during his Egyptian campaign. The Institut was burnt out on 17 December 2011 during the Revolution that had started the previous January. It is understood that Sheikh Sultan al Quassimi, Governor of the Emirate of Sharjah, will fund the the reconstruction of the building.

World Medals, Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha (1769-1805-1849), Wāli of Egypt, Centenary of Death, a large and impressive bronze medal, 1949, by Henri Dropsy (1885-1969), turbaned and bearded bust, head turned three-quarters r., rev. ships sailing from a harbour defended by cannon, cotton plant blossoming, legend on scroll, 118mm. (Dropsy, Paris 1964, 207), in green leather case of issue, much as issued, edition of 115 specimens, surface dull but extremely fine, an imposing and rare medal *bt. Baldwin Islamic Coin Auction 4, 8 May 2002 (lot 476) The reverse design displays items associated with the achievements of Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha.

British Coins, Henry VIII, third coinage (1544-1547), half sovereign, Tower mint, mm. pellet in annulet, king enthroned facing, holding orb and sceptre, rose below, rev. crowned shield of arms with lion and griffin supporters, wt. 6.07gms. (S.2294; N.1827), somewhat short of flan as so often seen but nearly extremely fine, the full-length robed and seated image of the famous king boldly detailed and finer than usually seen, his royal shield crisply detailed at the centre, fine flan-crack, in all a pleasing example of this classic Tudor gold coin

British Coins, Charles I, triple unite, Oxford mint, mm. plume/-, 1643, crowned bust l., holding sword and olive branch, plume behind, rev. Declaration on scroll between mark of value and date, three plumes above, wt. 26.70gms. (S.2725; N.2381), extremely fine on a broad flan, some alloy flecks on reverse, portrait exceptionally sharp, legends crisp and complete, rim beading bold on each side, some softness of strike on a few portions of the Declaration, surfaces pleasing with few abrasions, very rare and always in keen demand as the largest gold coin ever struck in England, and a classic of our Civil War The ancient university town of Oxford served as headquarters for the fleeing King Charles during much of the Civil War, and the active temporary mint there was a principal source of revenue for the Royalist army from 1642 to 1646. While this coin is universally admired today, at the time of issue its reputedly powerful image of the king was interpreted more as the vision of a chased monarch fearful of losing both his throne and his life, as of course actually did finally occur. Charles’s famous Declaration extolling the Protestant religion, the laws of his kingdom, and liberty granted to his subjects was made in a speech at Wellington in 1642, and it effectively set off the war. This, his largest coin, declares or promises to uphold those values but the coin itself was not seen by many subjects as its primary purpose was to purchase war materiel. Few of his wartime coins, certainly the largest ones carrying the highest purchasing power, survived long after conclusion of fighting. As Royalist forces had moved from one location to the next, pursued by Oliver Cromwell and his Puritan, parliamentary army, the coins tended to disappear almost as rapidly as they had been made, usually from plate, jewellery and older coins. Survival of a coin like this, essentially unblemished considering the ravages of its times, was really a matter of chance. Few of the total mintages from the three years of issue exist today, and all are prized as the ultimate expression in precious metal of the war which caused the traditional powers of kingship to change forever.

-

172550 item(s)/page