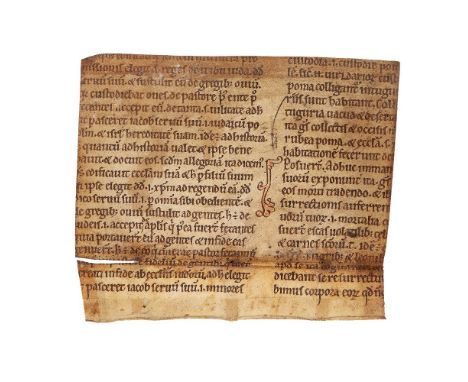

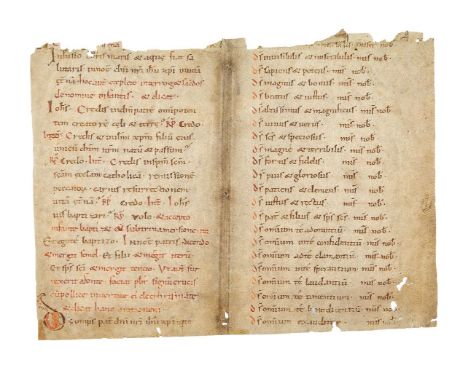

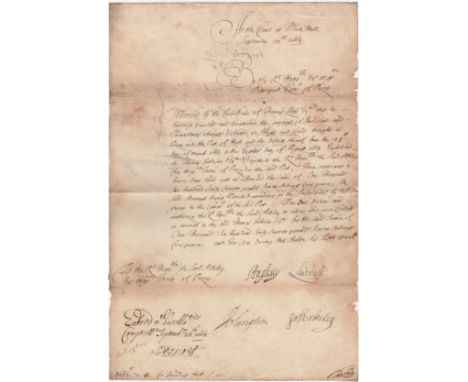

Cutting from a Psalter Commentary, in Latin, manuscript in parchment [England, late eleventh century or early twelfth century] Rectangular cutting, with remains of double column with 19 lines in a skilled English Romanesque bookhand, opening of Psalms marked by linedrawn acanthus leaf sprays touched in pale orange, some cockling, one large fold along base (causing splitting along gutter in places), some stains and scuffs from reuse as endleaf in binding of a later book, but overall in solid and legible condition and on good and heavy parchment, 95 by 115mm. From the library of Ampleforth Abbey, and sold by them some years ago.

33307 Preisdatenbank Los(e) gefunden, die Ihrer Suche entsprechen

33307 Lose gefunden, die zu Ihrer Suche passen. Abonnieren Sie die Preisdatenbank, um sofortigen Zugriff auf alle Dienstleistungen der Preisdatenbank zu haben.

Preisdatenbank abonnieren- Liste

- Galerie

-

33307 Los(e)/Seite

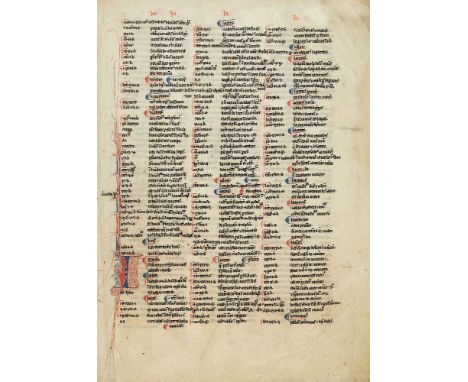

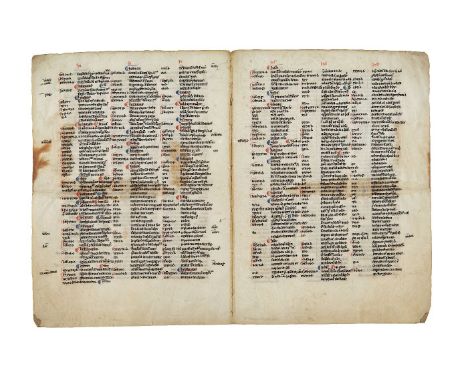

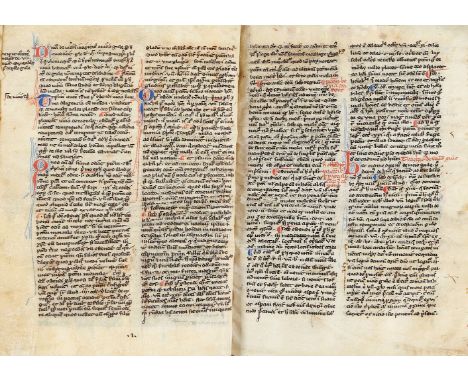

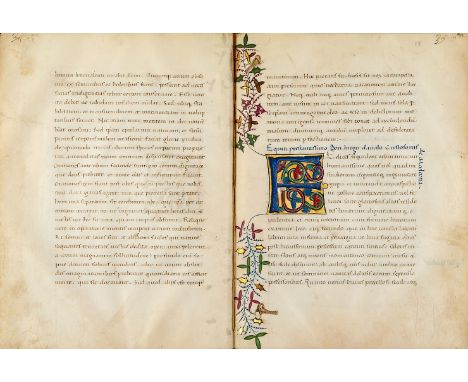

Bifolium from the Interpretations of the Hebrew Names from a notably large University Bible, in Latin, decorated manuscript on parchment [northern France or perhaps England, thirteenth century] Bifolium, one leaf with a large initial ‘I’ in variegated red and blue encased within scrolling penwork in same and with border of penwork tendrils and jagged leaf shapes filling almost the whole inner border, main text in three columns of up to 54 lines in small and squat university script with numerous abbreviations (entries from ‘h’ and ‘i’), paragraph marks and running titles in red and blue, remnants of leaf signature (formed of four vertical red penstrokes) in lower corner of recto of first leaf, slight cockling and stains to edges, folded horizontally across middle, else in good and presentable condition and on fine and heavy parchment, each leaf 350 by 240mm. The parent manuscript was a large and imposing volume, four times the size of its most common peers, and on a larger scale than the contemporary Northumberland ‘giant’ Bible, sold at Sotheby’s , 8 July 2014, lot 49. Precise localisation of thirteenth-century Bibles to either northern France or England is an imprecise art when one has the whole codex, but the setting out of the text here in three columns opens the possibility that the parent manuscript was English rather than the more common French. (cf. the same part of the text from the ‘Dring Bible’, sold in our rooms, 9 December 2015, lot 110).

Bifolium from the Interpretations of the Hebrew Names from a notably large University Bible, in Latin, decorated manuscript on parchment [France, or perhaps England, thirteenth century] Bifolium, text in three columns of up to 54 lines in small and squat university script with numerous abbreviations (entries from ‘i’ and ‘j’), paragraph marks and running titles in red and blue, catchword in lower corner of verso of last leaf, slight cockling and stains to edges, folded horizontally across middle, else in good and presentable condition and on fine and heavy parchment, each leaf 240 by 350mm. From the same parent manuscript as the previous lot.

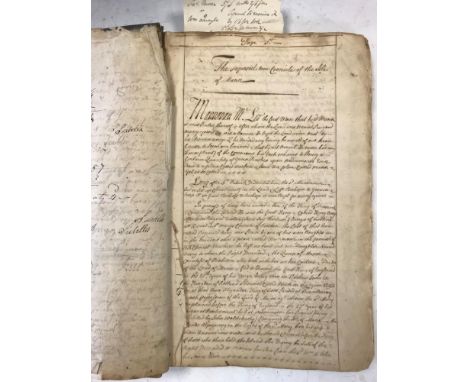

Leaf from a copy of Peter of Blois, Epistles, in Latin, manuscript on parchment [France, fourteenth century]Single large leaf, with single column of 34 lines in calligraphic secretarial script with numerous cadels and ornamental penstrokes, spaces left for initials, small amount of marginalia, prickmarks for ruling present, reused later by folding around the binding of a later book and so with splits along edges of that later binding, small holes and scuffed areas, reverse stained with some affect to text, obverse quite legible, overall fair condition, 362 by 256mm. The theologian and poet, Peter of Blois (c. 1130-c. 1211), is principally remembered as author of this letter collection. He studied at Tours and then Bologna, in the latter being taught by Baldwin of Forde (later archbishop of Canterbury) and Umberto Crivelli (later Pope Urban III). Thereafter his studies took him to Paris, and then on to Sicily to tutor the young king of the island. This step up in status set him on the career-path of diplomat in which letter writing would play the most crucial part, and drag him into the thorny debate between King Henry II of England and Archbishop Thomas Becket. He was part of a propaganda-based letter writing campaign focussed on this dispute, on the side of the king. After Becket’s death he served his successor Richard of Dover as well as Henry II, in roles we might now recognise as ‘spin doctor’ or publicist for both men. In 1176 he was appointed chancellor of the archbishopric of Canterbury, and thus the chief record keeper and secretary of the archbishop. This work is the fruit of the diplomatic labours of his last years, and these letters were collected together after his death and read as a collection for their moral, legal and theological instruction, as well as for their moments of wry satire.

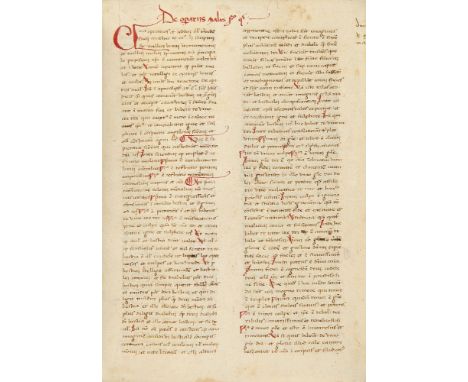

Single leaf from a compendium of Canon Law, in Latin, decorated manuscript on parchment [England, late fourteenth century] Single leaf, with double column of 38 lines in a professional bookhand with numerous cadels and decorative penstrokes (written space 180 by 133mm.), quotations underlined in red, capitals touched in red, paragraph marks in red or blue, running title in main hand within red penstrokes at head of page, original folio nos. “CXX” in upper corners of recto and verso, small stains, split in lower outer margin, tape at head of reverse from last framing, else excellent condition on clean and fresh parchment, 261 by 189mm. From a de luxe copy of a legal commentary, copied in the fourteenth century in a distinctively English secretarial hand, and on fine and white parchment. Additional note: Since going to press it has been drawn to our attention that this leaf is in fact from the same parent codex as two leaves sold in our rooms, 8 July 2015, lot 22, and contains a comprehensive theological manual, the Pupilli Oculi of John of Bury (d. after 1398).

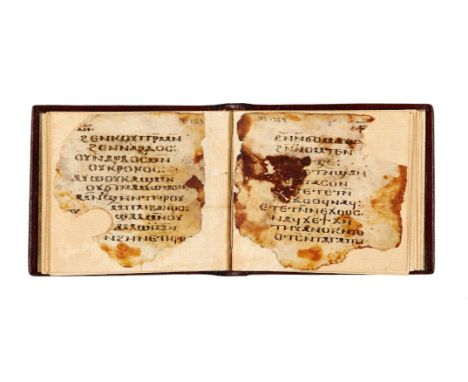

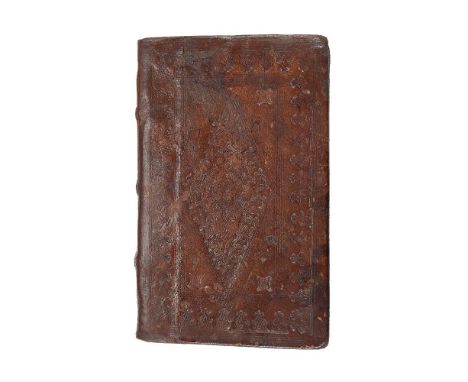

ƟBible, Cantica Canticorum (Song of Songs 4:12-14 and 5:8-9), in Sahidic Coptic, minuscule manuscript on parchment [Egypt, fifth century]Two leaves (once singletons), now bound as the central bifolium in a modern ‘support-codex’ setting, these preceded and followed by 17 modern paper and one modern parchment endleaves at front and 13 modern paper and one modern parchment at end, each original leaf with single column of 11 lines in a fine and delicate Coptic uncial hand, one large natural flaw in parchment of first leaf with text written around this, spots, stains and small splits, each leaf with wide margins, and measuring approximately 53 by 59mm.; modern binding of leather over pasteboards with Coptic blindtooling, in fitted cloth-covered slipcase with leather spine Provenance:1. Almost certainly written for a Coptic monk in Upper Egypt, perhaps in Wadi Natrun or Dishna.2. The Schøyen Collection, Oslo and London, their MS. 1363; both leaves acquired in London booktrade in early 1990s. Text:These two leaves are from one of the tiniest codices from Antiquity. Two further leaves survive from the same codex, once in the collection of P. Ramón Roca-Puig (1906-2001, papyrologist and priest), and bequeathed by him to the library of the abbey of Santa Maria de Monserrat, near Barcelona, where he spent his final years (published as S.T. Tovar, Biblica Coptica Montserratensia: P. Monts. Roca II, pp. 55-58, with Song of Songs, 4:8-9 and 8:2-4; and without knowledge of these here). Tovar noted numerous variants of the expected translation into Coptic, with sections of the original text omitted. Similar variants almost certainly await discovery on these leaves. The Coptic community was among the first to convert to Christianity, and is thought to have done so through the intercession of St. Mark the Apostle within years of the Crucifixion. This act, as well as the climate of the region preserving sites such as Oxyrhynchus has left us a better snapshot of Ancient Christian book practices here than anywhere else in the world. Among these are a handful of scattered remains of a fourth- and fifth-century phenomenon - the production of truly minute Christian codices. The most famous, as well as the most studied, is the fragmentary Mani codex of the fifth century, on parchment, which contains a Greek text of the life of Mani (the founder of Manichaeism). It was excavated near Asyut in Egypt (Ancient Lycopolis) and is now in the Institut für Altertumskunde, Cologne. That measures 45 by 35mm. but with its margins restored may have been a little larger (thus only a few mm. smaller than the present leaves). A third member of this group, P. Oxy V.840, a single leaf containing parts of a Coptic Gospel text of at least the second century AD., is a century older, but considerably larger (slightly less than 100mm. wide). Debate has raged about the function of these tiny codices, with some suggesting that they were amulets to be worn around the neck (P. Sellew, The Complete Gospels), while others have concluded this impracticable, and their small size due to private use and the need for portability (see M.J. Kruger in Journal of Theological Studies, 53, 2003, p. 93). T.J. Kraus observes that the two functions are not mutually exclusive (‘P.Oxy V 840 - Amulett oder Miniaturkodex’, Journal of Ancient Christianity, 8, 2004). However, no survey exists of such codices, and the present leaves are bound to play an important part in all future comprehensive research on the subject. Published online in the Leuven Database of Ancient Books, as LDAB 130506. Ɵ Indicates that the lot is subject to buyer’s premium of 24% exclusive of VAT (0% VAT).

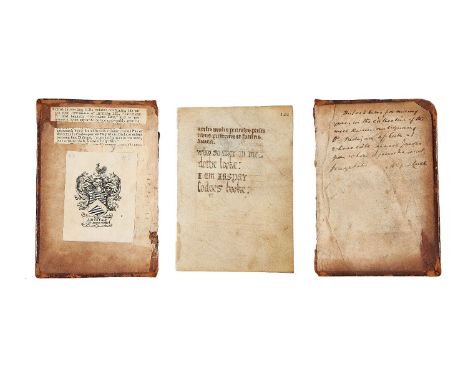

The last leaf from a Book of Hours with Tudor English ownership inscription in verse, and the front and back boards from its binding, manuscript on parchment [fifteenth, sixteenth and nineteenth century] Single text leaf with 3 lines from the end of a Book of Hours “… versis malis periculis presentibus preteritis et futuris. Amen” with an added Latin prayer of c. 1600 on the reverse, the end of the main text followed by a sixteenth-century verse ex libris in English (see below) filling the blank space there, the leaf numbered “101” in its upper outer corner, 105 by 72mm.; with front and back boards of seventeenth- or eighteenth-century brown leather tooled with simple fillet and floral stamps over pasteboards, each with later printed arms, cuttings and inscriptions (see below), some scuffs and stains This leaf and associated boards come from a miniature Book of Hours produced in Bruges in the mid-fifteenth century, most probably for the English market. A nineteenth-century label pasted to the front pastedown claims it once contained the signature of King Richard III, but this based on signatures of “Richard B” and “Richard Brg” on fols. 74v of the original volume. In the sixteenth century it was owned by one Jaspar Lodges, who added the ink inscription in a sixteenth-century hand to the last leaf here: “Whom so ever on me / dothe looke / I am Iaspar / Lodges booke”. The last marks here, that of the armorial bookplate and lengthy inscription on the front and back pastedowns identify it as subsequently owned by Alfred Cock of the Middle Temple, and note that he obtained it from the sale of the library of the “well known antiquary Nelligan”. It was last sold in Sotheby’s, 21 June 1994, lot 103, and thereafter widely dispersed.

ǂBible, Zechariah 14:21-Malachi 2:10, in Hebrew, manuscript on parchment [Oriental (Near East), tenth or eleventh century] Single large square leaf, with three columns of 22 lines of large square script with nikkud, Masora magna above text and Masorah parva below text, small Masorah inserted between the columns, small stains and tears to edges, else excellent condition and on fine and heavy parchment, 395 by 350mm.; in large folding custom-made card mount Provenance:1. Most probably from the famous Cairo Genizah, the repository of the Jewish community located in the Ben Ezra Synagogue of Fustat, established in 882 AD. This storehouse of obsolete texts fell into disuse and was forgotten until renovations to the building in 1891 opened the hoard and released some leaves onto the antiquities market. The linguist Archibald Sayce was in Cairo in 1892, and wrote to Neubauer describing how the Genizah was being dispersed leaf-by-leaf to collectors. Sayce repeatedly attempted to acquire the entire collection for the Bodleian (for ‘£50 and 5 bakshish’, ='blessing' meaning a tip), but negotiations fell through, and Sayce left Cairo blaming the constant inebriation of the local officials for the abortive attempt. Subsequently, a leaf from the long lost Hebrew version of Ecclesiasticus found its way via the redoubtable twins and early Bible hunters, Agnes Lewis and Margaret Gibson, to the Cambridge scholar Solomon Schechter. He mounted a rescue mission and acquired the remaining 140,000 fragments for Cambridge University. The discovery captivated public imagination in Europe in a way comparable only to the opening of Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922. For half a century, until the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, these were the oldest Hebrew manuscripts known.2. The Schøyen Collection, Oslo and London, their MS. 1630: acquired from Quaritch, London, November 1992. A sister leaf was sold in the Schøyen sale of ‘History of Western Script’, 10 July 2012, lot 12, for £42,000. Text: This is a noble relic of the earliest extant form of the Hebrew Bible in codex form, of equal or near-equal antiquity to the earliest surviving manuscripts. It should be noted that it is in the oldest extant codex format: nearly square with its text in three columns, echoing early papyrus codices, perhaps fixed in this format from the cutting up of Ancient scrolls and binding them together down one edge. The earliest surviving Hebrew biblical books date to the ninth or tenth century, such as the surviving parts of the Aleppo Codex (c. 920, now Jerusalem, Shrine of the Book), the Damascus Pentateuch (c. 1000; also Jerusalem, Hebrew University), the St. Petersberg Codex (dated 1008/09, now National Library of Russia, MS.B19a), British Library, Or.4445 (Pentateuch only, tenth-century), and the near complete ninth- or tenth-century codex, ex D.S. Sassoon, sold in Sotheby’s, 5 December 1989, lot 69, for £2,035,000. Those, and this leaf and its sister-leaves, are the fundamental witnesses to the format of the text as selected by the Masoretic scholar, Aaron Ben-Asher (d. c. 960), in Tiberias, modern Palestine. The resulting text was accepted by Maimonides as the most accurate, and remains in use today. The late Professor Chimen Abramsky assigned this leaf securely to the scribe of the tenth-century British Library, Or. 4445, and that manuscript’s lack of a eulogistic acronym for Aaron Ben-Asher has been taken as an indication that he was alive at the time it was written. Moreover, Kahle has suggested that Or. 4445 was the work of Ben-Asher himself in the early period of his work on the text (The Cairo Genizah, 1959, pp.117-18), placing the scribe of this leaf within the circle of Ben-Asher himself, at one of the formative stages of the Hebrew Bible. Published:D. Powell, Christian Apologetics, 2006, p. 189 (illustrated). ǂ Lots marked with a double dagger (ǂ) (presently a reduced rate of 5%) have been imported from outside the European Union to be sold at auction and therefore the buyer must pay the import VAT at the appropriate rate on the hammer price.

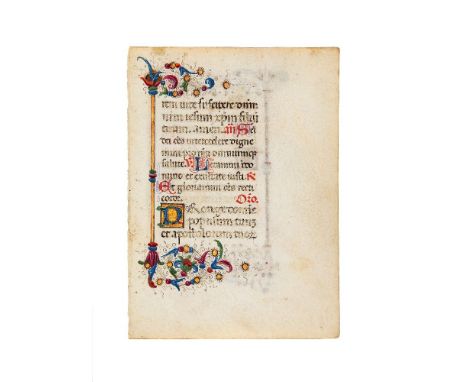

Leaf from a Book of Hours, in Latin, illuminated manuscript on parchment [Italy (probably Cremona or Ferrara), second half of fifteenth century] Single leaf, with single column of 12 lines in a late gothic bookhand (written space: 46 by 33mm.), red rubrics, one-line initials in red or blue with contrasting penwork, two 2-line initials in tiny blue, green and pink acanthus leaves on brightly burnished gold grounds, each page with a full text border on one vertical side formed from a single gold bar with coloured knots at centre and sprays of acanthus leaves, coloured flower-heads and bezants at head and foot, 95 by 70mm.; in card mount

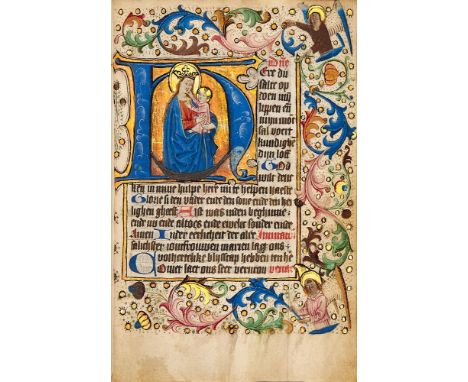

Presentation in the Temple, composite miniature from a Book of Hours, in Latin, illuminated manuscript on parchment [northern France, c. 1470] Single leaf, with a full page arch-topped miniature with the Virgin in sumptuous blue robes edged in white, kneeling before the priest and the Christ Child, as the child reaches towards her and meets her gaze, all before attendants and a hooded monk and within a gothic interior with elaborate gilt-edged wooden canopy at top of miniature, reverse with 10 lines of script, initials and line-fillers in liquid gold penwork on brown and burgundy grounds, the full decorated border around the miniature recovered from another leaf (probably from same parent volume) and skilfully married with miniature, this with acanthus leaves and coloured foliage and fruit on dull gold grounds, with two battling half-human drolleries in bas-de-page (both human heads and torsos and curved animal bodies ending in lions’ feet, and holding swords and bucklers), some tiny chips from Virgin and smudges to drolleries in border, else excellent condition, the whole 178 by 120mm. This charming miniature with its careful handling of facial expressions and love of intricate detail shows the artist to have been a skilled follower of Maitre François, who worked in Paris 1462-80, and whose style dominated the book arts of that city throughout much of the second half of the fifteenth century. Close comparison can be made between the figures here and those in a series of leaves bought by Dunedin in Sotheby’s, 25 April 1983, lot 151 (now Reed fragment 45: Manion and de Hamel, Medieval & Renaissance Manuscripts, 1989, no. 107).

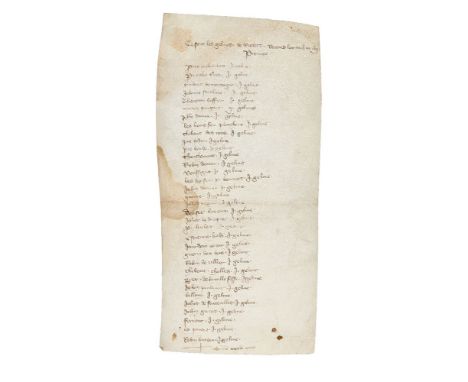

Rental roll for a French estate, in French, manuscript on parchment [central France (Rioubert, in Romorantin-Lantheney, dept. Loir-et.Cher), dated 1307] Single membrane with title:“Ce sont les gelines de Riobert. Receves lan mill.ccc..vii”, and 34 lines with entries of names followed by the amount they owed the estate in ‘gelines’, reverse blank, spots, stains, folds and two small holes in margin, else good condition, 238 by 114mm. What is most notable about this local record is that the payments recorded are all in “gelines”. This term is not easily reconcilable with any recorded currency, and the scribe may have meant actual chickens (Old French: géline or galine). This was presumably one of several lists for the estate, each listing an agricultural commodity, and to be loosely attached together in a bundle to form an informal estate record or terrier.

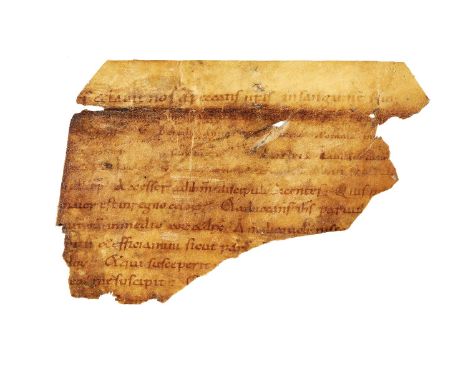

Small fragment from a service book, with music in St Gall neumes, in Latin, Carolingian manuscript on parchment [probably northern France, late ninth century] Small irregularly shaped cutting, with remains of 11 lines in a good Carolingian minuscule, capitals infilled with colour (perhaps once red, now oxidised and faded), 4 lines of text in smaller script with tiny neumes set above the words, text on reverse scuffed and obscured by once being painted over with black (apart from top line with ornamental capitals recording the reading there as for “[Sancti] Marci et Marcelli”), stains, splits and other flaws from having been reused in a later binding, 90 by 130mm. Carolingian neumes such as these represent the dawn of music in Western Europe. They seem to have evolved from ‘prosodic accents’, the acute, grave and circumflex that represent the inflection of poetry-recitation in late classical antiquity (and that survive in modern written French), but other theories place their origin in the hand signs used by singing masters or an adapted form of punctuation-signs from early Carolingian manuscripts. What is certain is that they were invented during the Carolingian era, and are only common in manuscripts from the tenth century onwards. These here come from the very earliest decades of such notation.

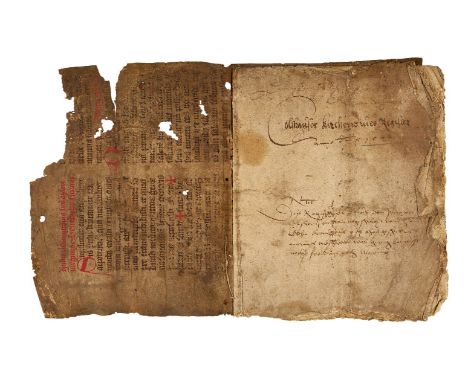

ƟAccount book for the church of “Colhauser”, manuscript, in German, on paper, bound in a parchment leaf from a fifteenth-century Lectionary [Germany (probably Kohlhausen, in Bad Hersfeld, Hessen), dated 1571, but with additions from first two decades of seventeenth century] 12 leaves, with scrawled entries recording payments owed to the church from a wide variety of local inhabitants (some lined through or crossed out, probably indicting they were paid), these mostly dated, placename appearing in form “Colhausen” in several places in the volume, “N3” on front cover, paper leaves a little woolly and occasionally folded, bumped and curled at edges, parchment leaf with tears and losses to edges, darkened and mostly illegible on outside, overall fair and presentable condition, 210 by 175mm. Kohlhausen is an outlying parish attached to Bad Hersfeld, in the valley to the immediate north of Fulda. It was first mentioned in the mid-fourteenth century, and converted to Protestantism in the mid-sixteenth century, immediately before the production of this set of records of the church there. Ɵ Indicates that the lot is subject to buyer’s premium of 24% exclusive of VAT (0% VAT).

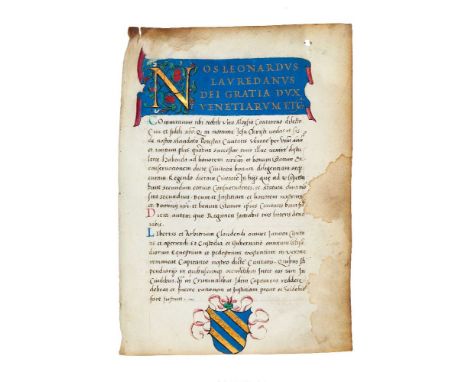

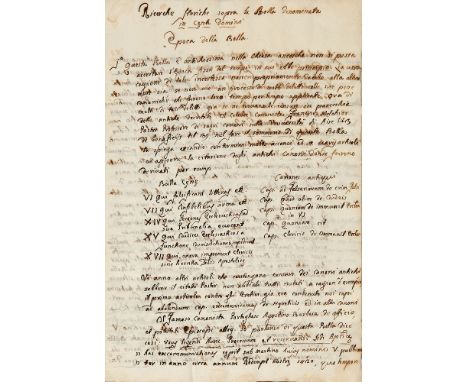

Opening leaf of a finely illuminated Venetian ducal commission appointing Aloysius Contarenus to office, in Latin, manuscript on parchment [northern Italy (Venice), first two decades of sixteenth century (probably 1520s)] Single leaf, with single column of 20 lines on obverse (28 on reverse) of fine humanist italic hand, simple initials in green, red and blue, opening lines in gold capitals on a blue banner with its red reverse revealed at its curling tips, opening initial in large gold bars enclosed with sprigs of strawberries, coat of arms of Aloysius Contarenus edged with swirling pink ribbon in central bas-de-page, small hole in upper margin, some stains at edges and with slight shrinking at upper inner corner resulting in small paint loss to upper corner of banner there, overall good condition, 225 by 158mm. Aloysius Contarenus served as consilarius to the Duke Leonardo Loredan (1436-1521: here “Leonardus Lauredanus”) of Venice in the early 1520s, and is recorded by Kristeller as something of a literary man: he was the subject of a text, Contarenus patriacha, which survives in Venice, Marciana, Zan. lat. 499 (1742) (Iter Italicum, VI, p. 253), and loaned out from his own library a poem on Aegidius Viterbiensis to enable the copying of Palermo, Bib. Naz., XIII C14 (ibid., II, p. 30).

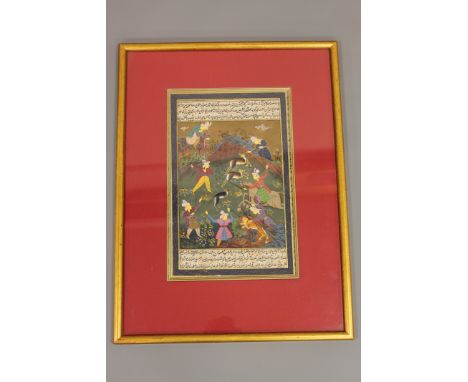

Twelve leaves from an Armenian Gospel Book, in Armenian, illuminated manuscript on paper [Armenia, seventeenth century] 12 leaves, including 8 with full-page miniatures (6 of these with edges restored and set in paper to form 3 bifolia): (i) Annunciation to the Virgin, with the angel kneeling before her as she sits; (ii) the Visitation of the Magi, set within an arched canopy; (iii) the Presentation in the Temple, with Simeon holding the Child before Mary and Joseph (who holds the two sacrificial doves); (iv) Christ washing feet before a crowd of onlookers, (v) the Crucifixion, with Longinus thrusting his spear into his side; (vi) the Three Maries at Christ’s Tomb, as the angel points at the shrouded corpse as three hooded soldiers sleep in the foreground; (vii) Christ’s entry into Jerusalem, seated on a donkey as worshippers climb colourful palm trees; (viii) Pentecost, with the Virgin standing between followers, her arms wide open as a mandorla opens in the sky above supported by angels and revealing Christ as a bearded man holding a book; each set within coloured geometric frames with square cornerpieces in contrasting colours, some small scratches and chips, and all leaves with losses at their edges (now skilfully restored with modern paper), reverses left blank in common Armenian fashion; plus 3 leaves from illustrated Canon Tables, with pillars topped with human heads, mirrored birds, a detailed peacock with brilliant plumage standing on a geometric architrave, a saint holding a scroll, and Christ in a mandorla on a sumptuous tessellated green background, these without losses to edges but some old spots and stains; plus a single text leaf with single column of 20 lines of bolorgir; each leaf approximately 182 by 120mm.

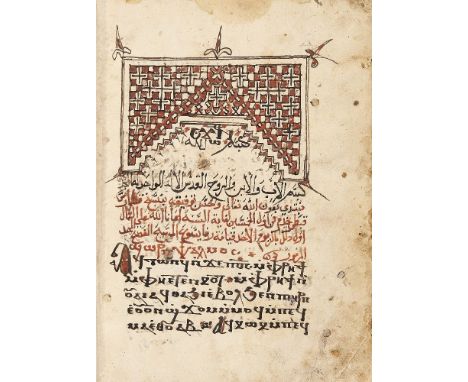

ƟMonumental Lectionary, in Bohairic Coptic with some colophons and rubrics in Arabic, decorated manuscript on paper [Egypt, sixteenth century (probably dated 1570)] 194 leaves (plus one original paper endleaf at back and 4 modern paper endleaves at each end), wanting 3 leaves from beginning, another single leaf after fol. 26, and 2 leaves at end, else complete, some leaves with gutters repaired and thus uncollatable, but every leaf with catchword, single column of 18 lines in an accomplished Coptic bookhand, capitals touched in red, large initials in red and black, the largest with geometric patterns leaving blank areas of paper within their bodies, others in form of red and black birds and a rounded human face staring straight out at the viewer, opening leaves with running titles set eitherside of crosses decorated in red, red rubrics, frontispiece with half-page geometric headband of crosses and red squares, the whole terminating in fleur-de-lys-like protrusions, occasional corrections or textual additions added vertically in margin, a few candlewax marks, Arabic colophons arranged mostly as triangular tailpieces at end of text columns, some splashes and small stains, small section of lower outer blank corner of fol. 1 torn away, overall good and solid condition, 332 by 235mm.; contemporary binding of dark leather tooled with clusters of flower-heads and double fillet over pasteboards, binding with old losses to corners and edges of spine, these now skilfully restored, and the whole codex strengthened and refreshened at same time, pastedowns reused from an apparent ledger, remnants of Arabic paper label on front board, in fitted cloth-covered case This is an exceptionally large format Coptic codex, presumably produced for communal use in a monastery or a Christian community in Egypt. It is dated in a lengthy colophon on fol. 170r, without month, on a Sabbath of what is most probably the year 1570 (the dating is in Arabic, but the order of the numbers has been inverted to follow Christian book practises). The scribe was greatly accomplished at writing Coptic, but less so in Arabic. By edict of Pope Gabriel II of Alexandria (70th Pope of Alexandria and Patriarch of the See of St. Mark) in the twelfth century, Copts were legally required to adopt Arabic and be proficient in it, and the shortcomings of the present copyist and the community he wrote for suggest a dogged refusal to comply and the assertion of his Christian identity. Ɵ Indicates that the lot is subject to buyer’s premium of 24% exclusive of VAT (0% VAT).

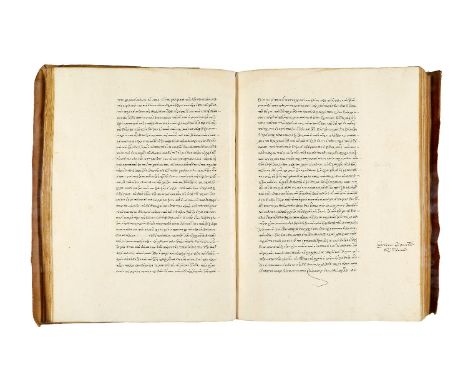

Ɵ Niketas Akominatos Choniates, Chronike diegesis (a contemporary chronicle of the Crusades to the Holy Land), in Greek, decorated manuscript on paper [northern Italy (Venice), dated 3 October 1541]312 leaves (plus 3 original endleaves at front and another one at back), complete, collation: i- xxxix8 (last leaf blank), single column of 30 lines in Greek cursive book script by the scribe Nicolaos Kokolos, rubrics and titles in faded red, small faded red initials set in margins, small number of contemporary marginalia, edges gilt and flecked with red, first 17 leaves of main text with a burn hole removing approximately 60 by 30mm. of 6 lines of text from inner edge of column, else in outstanding condition on remarkably clean paper in excellent state of preservation, 335 by 245mm.; contemporary limp parchment binding with yapp-edges, incorporating small strips from an Italian twelfth-century manuscript around first and last gatherings, small spots, cockling and slight darkening, else in outstanding conditionProvenance:1. Guillaume Pellicier (c. 1490-1568), French ecclesiastic of Montpellier and favourite of Marguerite d’Angoulême, the sister of the grand monarch François Ier. In 1533, the king stopped in Montpellier on his way to marry his son to Catherine de Medici, and Pellicier served in attendance of the court. Having come to the attention of François Ier he became a leading cultural figure of the court and was given offices in Rome and then as ambassador to Venice in 1539-1542. Venice was a key cultural centre for Italy, with a notable interest in Greek studies, and unlike almost all of Europe had resident Greek scholars and libraries as well as open diplomatic channels to the East. He used his time in Venice for bibliophilic purposes, acquiring large batches of Greek manuscripts for the Royal library at Fontainebleau, which were sent to France in 1542. The copy of the present text sent to France in that shipment was also produced in 1541, and it seems likely that that Pellicier executed his royal commission with slightly greater regard for his own collection than that of the king, and had three copies made, sending on only one to Fontainbleau. This is one of the others, as is another retained by Pellicier (and now Berlin, Staatsbibliothek gr. 236, also dated 1541, and sharing a provenance with the present copy through points 2, 3 and 4 below). His career was engulfed by an espionage scandal in 1542, and he was forced to return to France and retire to purely ecclesiastical duties. This carried on until 1551 when he was accused of concubinage, embezzlement of Church funds, and heresy, and incarcerated in the Chateau de Beaucaire. His library was seized, inventoried and judged in entries in the inventory as either condemnatus, suspectus or reprobatus (condemned, suspected or reproved; for the inventory see BnF., Par. Gr. 3068). He was condemned and ordered to pay the entire trial costs of 12,000 francs, but by 1557 had wriggled free and was a free man. It is to be noted that while Claude Naulot de Val (fl. 1570s), is often thought of an a subsequent owner of Pellicier’s library, he was in fact a registrar of the city of Autun, and his ex libri in the Pellicier manuscripts (here dated 1573 on frontispiece, and in tri-lingual Greek, French and Latin at end of text) were probably added in his capacity as legal secretary as part of the aftermath of the inventory of the collection when seized (A. Cataldi Palau, Catalogue of Greek Manuscripts from the Meerman Collection in the Bodleian, 2011, pp. 6-10).2. Jesuit College of Clermont in Paris, and acquired before 1651: with their ex libris at head of frontispiece: “Colleg. Paris Soctis Jesu”, and an inscription noting the decree of July 1763 (vertically down side of frontispiece: “'Paraphe au desir de l'arrest du cinq juillet 1763”, signed by ‘Mesnil’) which followed the near- bankruptcy of the French Order on the outbreak of war with England, and opened the way for the enemies of the Order to force their dissolution by royal order in 1764. The Péllicier manuscripts formed one of the founding collections of their library.3. Gerard Meerman (1722-1771), of The Hague, noted bibliophile and Baron of the Holy Roman Empire, whose wealth came from his father’s role as director of the Dutch East India Company, who travelled Europe in the 1740s acquiring entire libraries. His manuscript library was founded on the acquisition of that of the Jesuits of Paris, with the present volume published as Bibliotheca Meermanniana sive Catalogus Librorum Impressorum et Codicum Manuscriptorum, IV, no. 396. The collection was left to his son Johan, and became the basis of the collection of the Haagse Museum Meermanno. The manuscripts were sold at auction in The Hague in 1824.4. Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792-1892), the greatest manuscript collector to have ever lived; this his MS 6767 (written in his hand initially in pencil beneath his lion rampant inkstamp and then pen on front pastedown and with his distinctive paper label on spine), acquired in 1824 alongside much of the Meerman manuscripts (in fact he acquired nearly four fifths of the entire Meerman collection, individually and in person at the auction; but with the present volume apparently passing through the intermediate hands of Radinck, a bookseller of Amsterdam whose pencil inscription appears on the first endleaf). Published while in Phillipps’ collection by Studemund and Cohn (see below). His vast library passed by descent through his family until sold to the Robinson brothers (whose Pall Mall offices from 1930 until the retirement of the firm in 1956 were those we now proudly occupy). The vast majority of the Greek manuscripts from the Meerman library, some 241 volumes, were sold en bloc to the Preussiche Staatsbibliotek in Berlin in 1887, but this volume (alongside 32 others which were all shelved away from the main block in Phillipps’ library) remained in the Phillipps collection, and was sold by the heirs to the New York bookdealer, H. P. Kraus: his cat. 153 (1979), no. 94.5. The Schøyen Collection, Oslo and London, their MS. 562, acquired directly from Kraus. Text: Niketas Akominatos Choniates (c. 1155-1215/16) was the younger brother of the archbishop of Athens, and was a native of Chonai (modern Khonas, near ancient Collosae in Phrygia Pacatiana). As a child he accompanied his brother to study in Constantinople, but was free to pursue his own career as his elder brother fulfilled the family’s obligation to enter the priesthood. He served as an imperial under-secretary, briefly withdrawing from palace life in the 1180s due to the accession of the usurper, Andronikos I Komnenos, but returning on his sudden death in 1185. By 1189 he had been promoted to Grand Chamberlain of the Public Fisc, and so was personally involved in Byzantine government during Frederick Barbarossa’s passage to Thrace during the Third Crusade in 1189, with Niketas taking part in the destruction of the defences of Philippopolis, as well as trying to move the emperor towards support for the Third Crusade. In 1195 he was appointed logothete of the sekreta. The expulsion of Emperor Alexios V Doukas at the turn of the thirteenth century, also saw the downfall of Niketas’ career, and the destruction of his palatial home, which was consumed by a fire set by Crusaders. After the Fall of Constantinople in 1204 he withdrew to friends near Hagia Sophia, and ultimately walked with his family into exile. He witnessed the wanton destruction of the Crusading armies, and the wholescale breaking down and melting of Byzantine artworks into the component treasure parts. Ɵ Indicates that the lot is subject to buyer’s premium of 24% exclusive of VAT (0% VAT).

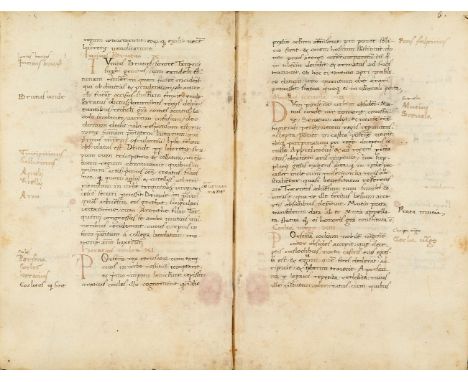

Leo the Great, Tractatus LXXII, in Latin, single leaf from a vast Carolingian manuscript on parchment [Germany (probably western Germany), first or second third of tenth century] Single large leaf, with double column ruled in drypoint for 33/34 lines in a skilled Carolingian minuscule, using et-ligature integrally within words, tall wedged ascenders, an ‘e’ with a long thin tongue, and a characteristic capital ‘S’ whose entire lower compartment sits below the line, simple capitals in same ink, trimmed at top removing only blank border, and at outer edge removing a few letters from the edge of the outer column, some folds, cockling and small stains and scuffs from reuse in the binding of a large volume, but overall in good and legible condition, 389 by 237mm. This is most probably the last surviving relic of a breathtakingly large Carolingian codex, presumably prepared for monastic reading.

ƟPresbyter Leo of Naples, Historia Alexandri Magni (Historia de preliis), in Latin, manuscript on paper [Italy (perhaps northern border with Switzerland), second half of fourteenth century]52 leaves (plus an original endleaf at front and back), complete, collation i-ii16, iii19 (last probably a singleton), catchwords within penwork designs (two-headed monsters, and elaborate cabouchon with crosses picked out within its body), single column with 28 lines in a fine and precise late gothic hand showing influence of Italian university script, initials in similar pen with ornamental strokes, the frontispiece opening with a large initial ‘S’ infilled with hatching and crosses and with simple line-drawn acanthus leaves filling margins on two sides, watermarks not very distinct but certainly a simple crossbow (arbelete) of the form in Briquet 701-09 (mostly Italy, including Pisa, Bologna, Siena, from 1320-1397) and perhaps also 710 (Paris, 1407-11), of these closest to 705 (Geneva, 1345-97) , later title “Vita Alexandri Magnis” at head of frontispiece (probably added in sixteenth century), gatherings strengthened at stitch-points and ends with small cuttings from a fourteenth-century Italian manuscript, small stains, else in outstandingly fresh condition, 192 by 135mm.; late medieval limp parchment binding stitched at head and foot of spine through parchment cuttings recovered from a medieval manuscript (probably thirteenth century), these placed flat against outside of spine, remains of two ties on vertical board, small stains and scuffs, else good and solid condition An excellent copy of the fantastic and enthralling life of Alexander the Great in the form known to most of the readers of the Middle Ages and later; still in its original binding, and a century older than the only other recorded copy to appear on the open marketProvenance:1. Written in the second half of the fourteenth century, probably by a northern Italian scribe, perhaps on or just over the Swiss border towards Geneva.2. In ethnically Italian ownership for the first century or so of its life, most probably in an ecclesiastical centre: endleaves used for scribal practise by a number of scrawling Italian hands (alphabets and common Classical quotations, and a riddle in Latin attributed to Albertus Magnus), in one case adding the date “Die 18 Junij 1527”.3. Rediscovered in a Swiss aristocratic family library.Text:Accounts of the life and deeds of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC.) attracted fabulous stories even in the Ancient World, and by the Middle Ages such accounts had become a blend of history and wild myth, offering their readers both instruction and entertainment in equal measure. Here the imagination of the European medieval reader could run riot, creating a fantastic world of staggering opulence and strange cultures and creatures, which were both startlingly alien and fascinating at the same time.The story here opens with the Egyptian sorcerer Nectnaebo’s seduction of Olympias, the wife of King Philip of Macedonia, while disguised as the god Amon, thus fathering Alexander. This is followed by Alexander’s youth in Macedonia and accidental murder of Nectnaebo, before his taming of the horse Bucephalus, tutoring under Aristotle and Callisthenes and ascension to the throne. The next section opens with his meetings with Apollo and Hercules and his military campaigns in Italy, Africa and the destruction of the city of Tyre. The author then includes Alexander’s supposed correspondence with Darius, king of Medea, followed by accounts of their battles in Persia, Alexander’s conquest of Asia Minor, and travels to Cilicia, Byzantium and Mesopotamia. Darius is then murdered by his own generals, and Alexander finds him on his deathbed and agrees to marry his daughter, Roxana. The invasion of India follows, with descriptions of its fantastical vast interior, including King Porus’ elephant army, breathtakingly opulent palace and love of music. The next section opens with a letter from Alexander to Calistradis, queen of the Amazons, and then describes Alexander’s encounter with dangerous river-monsters called “ypocami” (hippopotamuses), before fighting lions, bears, tigers and leopards, and observing crocodiles, scorpions and dragons of all colours and sizes, as well as a beast with three horns that was as strong as an elephant. A description of the phoenix follows, then Alexander’s correspondence with Dindymus, king of the Indian Brahmins, his travels in Nubia and meeting with twenty-two kings of Tartary, visit to the ocean at the end of the world, flights through the air on a griffon-drawn carriage and descent to bottom of sea in a primitive diving bell. This is followed by the death of the horse Bucephalus and a description of his tomb, before Alexander’s own poisoning with wine and a feather, and his dying farewell to a pregnant Roxana before dividing his empire among his generals. The text ends with Alexander’s death and burial in Alexandria with Ptolomy’s public mourning, before a description of his golden tomb, appearance and the twelve cities founded by him.This is the version through which the majority of medieval readers knew of Alexander’s life, and from which almost all early printed copies come. However, its textual descent is far from simple, and at many times has hung by the slimmest of textual threads. Its fundamental base is a compilation of Alexandrian material of probably the third century AD., once attributed falsely to the historian Callisthenes. Five or six redactions exist of it in Greek, as well as the so-called δ* line of descent, which does not survive in Greek, but is known only from the Latin translation made by Leo, a presbyter of Naples. He was sent in the mid-tenth century by Dukes John III and Marinus II of Campania to the Byzantine court in Constantinople on a diplomatic mission, and while there sourced a Greek exemplar of the text which he determined to translate for the readers of Western Europe. That translation, however, does not survive in its original form, but exists in three close but separate versions, each of which has its own lines of descent producing a wealth of varying witnesses, which spread widely and quickly throughout Europe. The version here shows some common features with a manuscript dated 1433 now at Harvard (Houghton Library, MS. 121).From the Middle Ages to the last century the text has remained stalwartly popular, and many manuscripts survive, with a handful in the grand private collections of the last century (including Martin Bodmer and Philip Hofer). However, these were acquired privately, and we can find only one other to ever come to the open market: a fifteenth-century copy sold in Sotheby’s, 12 May 1914, lot 27, from the collection of J.E.H. Morton (once Guglielmo Libri, acquired by Morton at his sale, London, Sotheby’s, 28 Mar. 1859, lot 35; and purchased in 1914 by the Houghton Library). We might also add the late fifteenth-century Flemish copy of the abridged text that appeared in Sotheby’s, 11 December 1972, lot 41, and note that only a tiny handful of the other available accounts of this ruler, all to some degree spin-offs of the present text, have ever appeared on the open market, and the last in Sotheby’s, 5 December 1989, lot 96. Ɵ Indicates that the lot is subject to buyer’s premium of 24% exclusive of VAT (0% VAT).

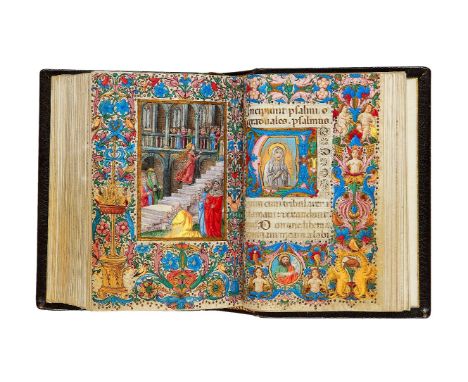

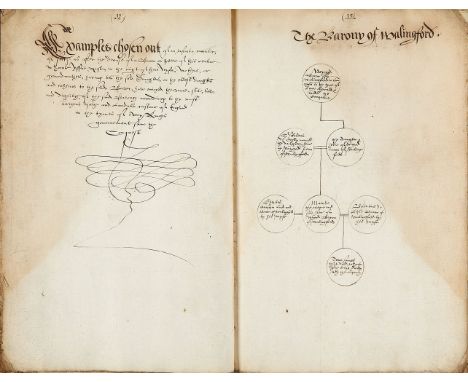

ƟThe Canterbury ‘Trussel’ Bible, with prologues of Jerome and Interpretation of Hebrew Names, in Latin, illuminated manuscript on fine parchment [southern England, or perhaps northern France, third quarter of the thirteenth century] 690 leaves (plus two original endleaves at front, and two at back), foliated in modern hand to include endleaves and followed here, uncollatable in usual fashion, but entire text checked and only one leaf missing (that with 3 Kings, end of 22-opening 23), else complete, double column of 44 lines of a legible and professional university hand in dark black ink, capitals touched in brick-red, occasional marginalia set within coloured penwork boxes, versal initials in alternate red or blue set both in edge of column and in adjacent margin, running titles in alternate red or blue capitals at head of page with penwork extensions, 2-line initials in red or blue with elaborate contrasting penwork encasing them and filling margins with vine-like foliage curls and jagged edged lines along the innermost edges of their descenders, sixty-six decorated initials in blue or soft pink, heightened with white penwork, often enclosing lacertine dragon-headed drollery creatures, with foliate shoots and gold bezants at corners pushing into margins, all on contrasting coloured grounds with tiny white penwork, seventy-two historiated initials in blue or soft pink enclosing Bible scenes and figures, with thin gold bars used as frame to their grounds, these often with thick bodied foliate extensions terminating in tiny leaves and gold bezants in borders (that opening prologue to Genesis with decorated bar borders in same on three sides of text), ten very large historiated initials containing figures with castle turrents, curled animals and other devices, with space filled within the bodies of the initial with lacertine winged dragons curling around to bite their own bodies and sprouting foliage from their tails, one full-page Genesis initial with seven scenes of the life of Christ set within quadrilobed gold frames with sharp points at the intersections of their lobes, all set on a single blue and pink decorated band and with elaborate head and foot pieces in margin or swirling and interlocking foliage terminating in small leaves and gold bezants, many leaves with original alphabetical quire and leaf signatures, smudging to details of two initials, white paint of faces partly oxidised to grey in places, natural flaw to parchment on fol. 263, small number of mistakes by the painter of the versal initials (in form: missing numeral on fol. 184v, subsequently corrected by dropping ‘xvii’ later in text; and ‘xxxii’ on fol. 344v where he should have written “xxxiv’, thus ‘xlii’ repeated twice on fols. 347v-48r), small dark spotting in inner gutter on fols. 325v-326r, small losses to top of leaf in opening text of John (affecting only a few characters in uppermost 8 lines), two or three wormholes in first leaf, trimmed at edges with losses to running titles, else in very good condition, 174 by 115mm.; early nineteenth-century blue morocco, tooled with frames of rollstamps around a central rectangle of angular floral bosses, the outermost frame profusely gilt with floral designs, spine gilt tooled in compartments with “BIBLIA LATINA / MS / CIRC. 1353” (see below), outermost edges of inside of boards also profusely gilt, pale blue watered silk pastedowns and doublures (so close to the binding of another Bible ex Yates Thompson collection, and sold last in our rooms, 9 December 2015, lot 111, to suggest the same binder), the width and weight of the volume causing the binding to separate from the book block at front and back, now nearly loose in binding and held in place only by silk doublures (these with tears where binding attaches to volume), two thongs snapped in Pauline Epistles, but overall in solid and presentable state, gilt edgesThis is a fine thirteenth-century Bible, produced in a de luxe format with nearly one hundred and fifty decorated initials, probably in England. Only the tiniest handful of such Bibles surviving today have any secure medieval provenance, but this was demonstrably in the library of Canterbury Cathedral, the absolute epicentre of Christian worship in the British Isles, throughout the Middle Ages; and bears on its endleaf the signature of one of the last members of the community before the Reformation, who presumably took it with him. From there it passed through the hands of Thomas Rawlinson, “the Leviathan of book collectors”, and thereafter to the libraries of an important British theologian, a Liberal politician and a Mayfair aristocrat. It has not appeared on the open market in nearly forty years and is now the very last recorded manuscript codex in private hands from this most important of English monastic libraries Provenance:1. The Cathedral Priory of the Holy Trinity or Christ Church, Canterbury, the mother church of the English people and the central site of English Christian life: with an erased inscription on front original endleaf, but read with ultra-violet light: “Eccl[es]ie chr[isti] cantuarie” (most probably very late thirteenth or fourteenth century). The cathedral was founded by St. Augustine in 598 as his own seat and that of his successors, within the structure of the royal palace of King Æthelberht of Kent, itself reportedly of Roman origin. As a church rather than a monastery, Christ Church’s community consisted of secular canons up to the Norman Conquest, with monks introduced after the Norman Conquest by Archbishop Lanfranc. Since then, it has been the mother church of Christianity in the British Isles, perhaps the most important pilgrimage site in England, the site of the martyrdom of St. Thomas Becket, as well as the burial place of the archbishops of Canterbury and Edward Plantagenet the Black Prince, and Henry IV. As the absolute focus for English devotions, it has loomed large in the English-speaking imagination, with William of Malmesbury in his Gesta Pontificum claiming of it that, “Nothing like it could be seen in England either for the light of its glass windows, the gleaming of its marble pavements, or the many-coloured paintings which led the eyes to the panelled ceiling above”, and Chaucer using it as the ultimate destination of his fictitious pilgrims in his Canterbury Tales. The present manuscript is probably English in origin (see below), and was published as such by Sotheby’s in 1967 and the late Jeremy Griffiths in 1995. If this is correct, then it must come from a large scribal and intellectual centre, such as Oxford or Canterbury. It may be identifiable as one of a small number of complete bibles in the early fourteenth-century booklist of the community (edited by M.R. James, The Ancient Libraries of Canterbury and Dover, 1903, no. II) as item 600 (“Biblia”), or among the additional material at the end of that list, recording books of former members bequeathed to the community. Of these, only six Bibles were given by men who lived after the present manuscript was copied: (i & ii) items 1639-40, two bibles from the collection of Archbishop Robert Winchelsey (reigned 1245-1313); (iii) item 1722, from ‘John of Thanet’ (presumably the early fourteenth-century monk of the same name from whose cope a panel still survives, embroidered with his name and profession, now Victoria & Albert Museum T.337-1921); (iv) item 1731, from ‘Robert Poucin’; (v) item 1773, from ‘William of Ledbury’; and (vi) III:1, that from the collection of Prior William of Eastry (held office 1285-1331). Ɵ Indicates that the lot is subject to buyer’s premium of 24% exclusive of VAT (0% VAT).

ƟWilliam Peraldus, Summa de vitiis, in Latin, decorated manuscript on parchment [France (perhaps central), late thirteenth century] 224 leaves (plus one modern paper endleaf at each end and an original parchment endleaf at front), wanting a single leaf after fol. 101, else complete, collation i-iii8, iv12, v-vi8, vii10, viii8, ix12, x10, xi11 (last but one wanting), xii8, xiii12, xiv10, xv8, xvi12, xvii-xviii10, xix12, xx2, xxi10, xxii-xxiii8, xxiv12, contemporary leaf signatures in red, with quire signatures until tenth quire then sporadic catchwords, double column of approximately 35 lines in a number of tiny and leaning university hands, with curling cadels in places in lower margins, red rubrics, red or blue paragraph marks, simple initials in red and blue with penwork to contrast, some spaces left for other initials, initial in frontispiece on red and blue with bi-coloured penwork, some marginalia, one leaf once with a devotional miniature (planned as part of the original layout, but now wanting, leaving only paste-marks from its edges), slightly trimmed at edges (but many leaves with original prickmarks from ruling), some cockling and natural flaws to a number of leaves, small rustmarks to first original endleaf showing earlier binding had two clasps held in place by iron nails (marks on inside of this leaf suggesting another devotional miniature once pasted there), overall fair condition, 170 by 120mm.; nineteenth-century brown tooled leather over pasteboards, scuffs to edges This is a charming and stout thirteenth-century codex with a noble French provenance, and of a date and possible origin which may place it close to the author and the earliest manuscripts of the textProvenance:1. This volume is a little too homespun to have been produced in a large and populous centre such as Paris, and the irregularities of its hands and later history may indicate an origin in central France instead, perhaps in the Auvergne. The first owner, or at least a near-contemporary one, added the textual observation in French: “Le vin broutin est fally” (probably ‘the eighth paragraph is wanting’) in large script at the head of fol. 123r.2. Claude Etienne-Annet (1754-1823), marquis des Roys, seigneur d’Echandelys in the Auvergne, politician and captain in the regiment de Dauphin-Cavalrie: his armorial bookplate inside front board. He is not recorded as great book collector who sought acquisitions from far afield, but he did live through the French Revolution and the secularisation of the monasteries of France. 3. Roque Pidal y Beraldo de Quirós (1885-1960) of Madrid, the grandson of the marquis de Pidal, and a substantial antiquarian and bibliophile with large collections of manuscripts and incunables: his label on front board noting this codex was deposited along with his other manuscripts in the Biblioteca Nacional for some time (this his MS. 12). Part of his collection passed to his alma mater, the University of Oviedo, in 1935, and the rest was dispersed by his heirs.Text:William Peraldus (c. 1190-1271) was a Dominican preacher from Peyraut in the Ardèche. He studied in Paris before entering the Dominican Order, rising to become prior of the community in Lyon in 1261, where he waited in attendance of Philip I, count of Savoy and archbishop of Lyon. His magnum opus was this work, the Summa de Vitiis, mirrored by his later sister-composition, the Summa de Virtutibus. That here deals with the seven capital vices and sins, and spread widely throughout Europe as a practical handbook for preaching. It survives in over 500 manuscripts, often from Dominican and Franciscan communities, but what sets the present manuscript apart as of potentially great textual importance is its date and the probable geography of its origin. It is notably early, written within the lifetime of the author or in the years immediately following, and probably from the same region as that in which the author worked, the Auvergne (Echandelys sits some 30 miles to the west of Lyon). The codex here includes the Summa de Vitiis on fols. 1-221r, followed by an antiphon sung at the Mass of St. Paul’s crucifixion (28 April): “Christus passus est pro nobis …”. Ɵ Indicates that the lot is subject to buyer’s premium of 24% exclusive of VAT (0% VAT).

ƟBernardinus of Siena, Sermones extraordinarii, in Latin, decorated manuscript on paper [Italy (perhaps Genoa), mid-fifteenth century] 221 leaves, wanting single leaves at front and end and a blank cancel in fifteenth quire, else complete, collation: i11 (i wanting), ii- xi12, xii10, xiii-xiv12, xv11 (i a blank cancel), xvi-xviii12, xix9 (wants last), some remnants of catchwords, double column of 43 lines in a tiny late gothic bookhand, sermons ending in “AMEN” in capitals, some paragraph marks and rubrics in red and a handful of red initials (many spaces left for others), watermark a fleshy lobed three pointed crown surmounted by a cross closest to Briquet 4596-9 and 4630 (but these all fourteenth century apart from the last, that recorded Genoa, 1415/16), the text on the last leaf of the fourteenth gathering ends abruptly mid-page and the scribe then left two blank leaves before resuming (one of which was subsequently excised), this may be due to a fault in the scribe’s exemplar, causing him to leave approximately two blank leaves to be filled at a later date when another copy could be sourced, a number of leaves throughout repaired along gutter with strips from a number of thirteenth-century devotional manuscripts on parchment, first and last leaves a little damaged at edges and with small stains, trimmed with damage to topmost lines of script on a few leaves at end of volume, overall in good and solid condition, 236 by 175mm.; early sewing structures (including pieces of fifteenth-century Italian choirbook reused inside spine), now encased within later binding (probably seventeenth- or eighteenth-century) of pasteboards with parchment spine stamped with ink fleur-de-lys An important record of popular religion in fifteenth-century Italy, of extreme rarity to the market, and perhaps written within the lifetime of the author Provenance:Written in the middle of the fifteenth century, perhaps in Genoa: the watermark of a simple fleshy lobed three pointed crown surmounted by a cross, is of a form usually confined to the fourteenth century, but with a single Genoese example recorded for 1415/16. This is a large format volume, more probably written for the library of a Franciscan convent rather than for itinerant preaching. By the seventeenth or eighteenth century it was certainly in a Franciscan convent (their ex libri with place name erased on fol. 164v and again in the central margin of fol. 173r), and it may well have always been there. The Franciscan presence in Genoa dates to at least 1226, by which time their church had been erected, and from there spread out to foundations in the surrounding towns. Text:Bernardino of Siena (1380-1444) was one of the most important preachers of the Franciscan Order, whose passion and fervour of oratory helped shape the identity of that monastic movement. As a young man he renounced his studies and joined the Confraternity of Our Lady attached to the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala, Siena, and when plague struck the town later he remained to administer to the sick and dying. This experience and his apparent miraculous survival set him on the path of a religious preacher, and in 1403 he joined the Franciscans. He differed from his predecessors in his focus on preaching to the public in simple language without prepared speeches and notes, and travelling everywhere by foot. Despite having what was described as a weak and hoarse voice, he drew commanding crowds and played a substantial role in the popular religious revival of fifteenth-century Italy. He rose in prominence to be regarded by Franciscans as Bernard of Clairvaux was for the Cistercians - not their founder, but a primary driver of the early movement. He served as Vicar-General of the Order, but forced the Pope to accept his resignation in 1442 so he could return to preaching. He died in L’Aquila in the Abruzzi in 1444, and his grave is reported to have leaked blood until the two warring factions of that city reconciled their differences. His asceticism and spurning of luxuries provides a contrast to what we usually associate with Renaissance Italy and its opulent courts, and allows us a glimpse into the popular culture of fifteenth-century Italy. The sermons here are his Sermones extraordinarii, and the Latin texts here cover the main subject matter of each extemporised sermon, here set down for contemplation and inspiration. They are rare in manuscript, and no other copy of this important work on the open market is known to us, with the sole possible exception of that sold by Evans, 17 January 1840, lot 176, as part of the Piccolomini collection (described there as “Sermons”, and so just as likely one of the other four sermon collections of this author). Ɵ Indicates that the lot is subject to buyer’s premium of 24% exclusive of VAT (0% VAT).

ƟTibullus, Elegae ad Messalam Corvinum, in Latin verse, illuminated manuscript on parchment [Italy (probably Italy), late fifteenth century] 42 leaves, (plus an original endleaf at front and back, and including last 5 leaves blank), complete, collation: i-iv8, v10, some catchwords and original quire-signatures, single column of 38 lines of a fine humanist italic hand, rubrics in purple-red, simple green, blue and gold initials, major breaks opening with gold initials on brightly coloured square grounds, many pointing finger marks in coloured inks (some elaborate, and two holding banderoles with “Nota”), one large initial ‘D’ on frontispiece, in blue edged with white, enclosing in green curling foliage, all on burnished gold grounds, enclosed within bezants and ornate penwork, coat-of-arms in bas-de-page of same, corner of second leaf torn away (without affect to text), one initial smudged, a few leaves with folds and faint traces of earlier letters suggesting that some of parchment was recovered from other documents or books, overall in clean and fresh condition on fine parchment, 172 by 105mm.; in a contemporary binding tooled with ropework designs, chevrons filled with dots and lines of crown-like stamps over pasteboards, spine skilfully rebacked leaving volume a little tight, in fitted card slipcase Provenance:1. Written and illuminated for the noble patron whose arms appear in the bas-de-page of the frontispiece. The arms are not easily identifiable, but the later history of the book suggests that they were those of a southern Italy noble patron, perhaps from the Neapolitan court (which are comparatively poorly recorded).2. Girolamo Angeriano (c. 1480-1535), the Apulian Italian humanist, poet and member of the Pontanian Academy, who retired at an early age from the Neapolitan court to family estates in Ariano di Puglia: his partly-erased inscription “Hieronymi Anghierie et amicorum” at head of recto of first leaf. Perhaps his series of letters arranged in a diamond above the Catalan motto “Por no dexar” on first endleaf.3. Carlo Morbio (1811-1881), Milanese collector and historian, author of Storie dei municipi italiani; his sale in Leipzig, 15-16 July 1889, no. 599, acquired there by von Wilmersdörffer for 16 marks.4. Max von Wilmersdörffer (1824-1903), banker and coin collector; his large armorial coloured bookplate dated 1897 pasted to first endleaf.5. Lambert Schneider (1900-1970) of Berlin, prominent publisher: his small printed bookplate inside front board. His catalogue card in German loosely enclosed, noting this as his no. ‘11091.2’.Text:Tibullus (or Albius Tibullus, c. 55-19 BC) was a Roman nobleman and composer of elegies, who lived in the turbulent period following the abolishment of the Roman Republic and the establishment of the Principate of Augustus in 27 BC. He rose to prominence in the Roman literary circle of his patron, the general Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus, and may have accompanied the latter on military excursions in Gaul. He seems to have lost most of his estates during the confiscations of Mark Anthony and Octavian, and died early, but nonetheless was widely celebrated in Rome with Ovid composing an elegy for him (this among the last items in the present volume). This volume open with a short biographical introduction (fol. 1v), followed by the four books of his works as the Middle Ages understood them to be: book I (fol. 2r, opening “Divitias alius fulvo …”), book II (fol. 15v, opening “Quisquis adest faveat …”), book III (fol. 23r, opening “Martis romani festae …”) and book IV (fol. 28r, opening “Te messala canam …”). The first two are certainly his work, but the latter two are in fact more likely that of poets in his immediate circle. Among these early accretions are verses named as the work of Sulpicia - the only extant poems by a female author from ancient Rome. The volume ends with Ovid’s elegy, De morte Tibullus (fol.35v) and other shorter elegies for him in purple-red ink. While no extant copy predates the late fourteenth century, one certainly did exist in Carolingian aristocratic circles, and is named in the famous and much discussed eighth-century list of Classical authors in Berlin, MS. Diez B.66. That manuscript, or a copy of it, passed to Fleury where it was used by Theodulf (d. 821) and then Orleans where echoes of it appear in the twelfth-century Florilegium gallicum. Richard de Fournival, chancellor of the Cathedral of Amiens (1240-1260) bequeathed one to the Sorbonne, and another was at Monte Cassino. The earliest surviving manuscript is that produced for the great Florentine humanist, Coluccio Salutati (1331-1406; Milan, Ambrosiana R. 26 sup.), and from this copy an explosion in popularity ensued, so that well over a hundred manuscripts are known from the fifteenth century (see G. Luck, Albii Tibulli aliorumque carmina, Teubner, 1988). That said, they rarely appear on the open market, and the last appearance at auction was in 1979 (Sotheby’s, 19 June, lot 44). To that should be added a copy sold privately in 2011 by Les Enluminures. Ɵ Indicates that the lot is subject to buyer’s premium of 24% exclusive of VAT (0% VAT).

ƟBasil of Caesarea, Epistola ad Adolenscentes, in the Latin translation of Leonardo Bruni, and Basil of Caesarea, Epistola ad Gregorium Nazanzenum, in the Latin translation of Francesco Filelfo, with a short contemplative text by St. Augustine and letters addressing the Neapolitan courtier, Iñigo d’Avalos, in Latin, illuminated humanist manuscript on parchment [Italy (Milan), c. 1440-c. 1450] 64 leaves (plus a modern paper endleaf at each end), wanting single leaves after fols. 12 and 22 and a bifolium from first gathering (and thus since before the earliest pagination in the seventeenth or eighteenth century), else complete, collation: i6 (wants central bifolium), ii7 (wants last but one original leaf), iii10 (with bifolium bound into second half of quire, wants last but one leaf and last leaf a singleton to complete text), iv-viii8, ix9 (last leaf a singleton to complete text), catchwords, paginated and foliated a number of times since the seventeenth or eighteenth century, single column of 24 lines in a fine and accomplished humanist hand, rubrics and some reference words in margins in bright blue, small initials in green, blue or pink with sprigs of coloured foliage on brightly burnished gold grounds, terminating in sprays of single line blue and red foliage with coloured baubles on their stems and tiny gold leaves, four large illuminated initials in green, blue and burgundy, heightened with white, enclosing stylised foliage and on large burnished gold grounds, the frontispiece with similar initial as well as a full border of split blue bars on gold grounds with angular gold and coloured foliage, large bezants with radiating penwork strokes each ending in dots and coloured acanthus leaves, coat-of-arms in bas-de-page surmounted by helm and wheatsheaf that of Iñigo d’Avalos (see below), some trimming with loss to bottom of arms and edges of border in places, some stains to edges of leaves, one initial very slightly smudged, a few later marginalia (probably sixteenth century), else in outstanding condition on clean white parchment, 222 by 173mm.; nineteenth-century brown tooled leather over pasteboards, front board slightly bowed inwards and splits to leather at foot of spine, spine gilt-tooled with title This is an elegant humanist volume, in the distinctive style of Milanese Renaissance books, from an important library of a Neapolitan courtier whose library was lauded by Vespasiano de’ Bisticci; most probably passing after his death into the Royal Aragonese library, one of the greatest manuscript collections to have ever existedProvenance:1. Doubtless commissioned by Iñigo d’Avalos (c. 1420-1484, also Innigo, Innico, Enecus, Aenicus and Enyego, with his arms on frontispiece: “d’azzurro alla torre con tre torrette merlate d’oro, con la bordure composite di sedici pezzi alternate d’argento e di rosso”, note that the ‘alternative opinion’ for the same arms in another book of his now in the Houghton Library, kept in their curatorial file for the volume and repeated by the Schoenberg database, is to an outdated and erroneous report). The present volume was most probably produced to set the letters of “Christophorus modoetiensis” (most probably the Milanese intellectual and Franciscan author, Christoforo Pisanello) to Iñigo, each a work of humanist scholarship in itself, in an illuminated codex, alongside translations by Leonardo Bruni and Francesco Filelfo, which Christoforo may have presented to Iñigo. Iñigo served as close advisor and courtier to King Alfonso I ‘the Magnanimous’ of Aragon, Sicily and Naples, and acted as Neapolitan ambassador to the Visconti court at Milan. He was a Spaniard from a Castilian noble family, who came to Italy in the wake of Alfonso I, and rose quickly through his court. In 1435, he was stationed in the Visconti court, as one of two Aragonese officers ordered to protect Filippo Maria Visconti, and his links with the cultural life of Renaissance Milan endured long after this. On his return to Naples he was appointed commander of the Spanish troops, and in 1449 he became a royal ‘camerlengo’ (Grand Chamberlain), and in 1452 was given the lordship over the town of Monteodorisio. He continued in his offices under Alfonso I’s heir and successor, King Ferdinand I, from 1458. Iñigo warmly embraced the intellectual fruits of the Renaissance, and the access to rare books that his connections in the Neapolitan and Milanese courts brought. Vespasiano de’ Bisticci, the grand Florentine commentator on the Renaissance, gives a description of Iñigo and his library that is so close as to suggest that they knew each other personally. Iñigo, he says, was a bibliophile and a great commissioner of humanist books, who was “Dilettosi meravigliosamente di libri, et aveva in casa sua una bellisima libreria, tutti libri degnissimi di mano de’ piu begli iscritori d’Italia” (a most marvellous dilettante of books, and had in his house a beautiful library, with wondrous books by the hand of the principal scribes of Italy), and notes his books “tutto cio richiami ad un clima umanistico ben preciso” (all recalled a precise, humanistic atmosphere). He was a substantial patron of the arts, standing as protector to celebrated humanist scholars such as Pietro Candido Decembrio, Francesco Filelfo (who dedicated one of his Satyrae to him in 1453), and probably also Thomas Guardati of Salerno (who dedicated his twelfth novella to him and his twenty-first to Iñigo’s wife). In addition, his portrait was cast a medal c. 1449 by Pisanello (New York, Metropolitan Museum, Lehman collection, 1975.1.1299). 2. Most probably in the Royal Aragonese library in Naples from 1484: on the death of Iñigo d’Avalos, his library is reported to have passed into that institution (T. de Marinis, La biblioteca napoletana dei re d'Aragona, I, 1952, p. 41), one of the greatest collections of humanist manuscripts and Classical texts to have ever existed. Unfortunately, this library shared the vicissitudes of the dynasty who built it, and in 1496 it passed to the youngest son of Ferdinand I, Federico of Aragon (1452-1504). When he was forced to yield the kingdom to Louis XII of France in 1502, the library was removed from Naples, with parts of it purchased by Louis XII and Cardinal Georges d'Amboise (1460-1510), archbishop of Rouen. The substantial remnant remained with Federico, and passed in turn to Isabella del Balzo, his wife, who sold a number of water-damaged volumes to the humanist Celio Calcagnini in 1523. A final portion of over 300 books was shipped to Valencia in 1527 where she and her son had taken up residence. They were then slowly dispersed (see the Statius, Thebaid, Achilleid and Silvae from the Royal Aragonese library, sold in Sotheby’s, 10 July 2012, lot 27, on behalf of a Spanish private collection, and incidentally also wanting a number of illuminated leaves). The recorded volumes from the library of Iñigo d’Avalos are now scattered between Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom and North America (see below). Text: The volume opens with an undated and evidently unpublished letter from “Christophorus modoetiensis” (see below) to Iñigo d’Avalos (fol. 1r), discussing the authors of the following two texts (as well as a host of other Greek authors) and the translators of those texts: Leonardo Bruni (here with the surname ‘Aretinus’) and Francesco Filelfo. This letter is in a fine humanist copy here, but seems to have accompanied an earlier gift of a book (perhaps the exemplar of this one). It signs off “Ex urbe Mediolanensi populosa”, ‘from the populous city of Milan' Ɵ Indicates that the lot is subject to buyer’s premium of 24% exclusive of VAT (0% VAT).

ƟHumanist Compendium including Pseudo-Pliny, De viris illustribus, Leonardo Bruni, Commentariorum primi belli punici, Cicero, De senectute, a text on Aesop, and Jerome’s Vita Malchi monachi captivi, Vita Pauli heremitae, Vita Hilarionis, Vita Athanasii, with letters of Jerome, in Latin, manuscript on paper and parchment [Italy (perhaps Mantua or Siena), dated 1460 and February 1461] 190 leaves, complete, collation: i11(last a singleton), ii-iii8, iv10, v-viii12, ix14, x-xii12, xiii13 (last probably a singleton to complete text; no loss to text here), xiv-xvi12, xvii6 (last 2 leaves blank cancels), catchwords, seventeenth-century foliation (followed here), single column of 32 lines in a good humanist hand, rubrics and some small initials in vivid red, others in faded red, two large white vine initials in penwork, a few quires with outermost leaves of parchment, watermark a column surmounted by a crown, close to Briquet 4411 (Mantua, 1460, as well as Rome, Naples, Florence and others in same period) and 4412 (Siena, 1465), nineteenth-century “No 176” at head of frontispiece, some spots and stains, a few leaves faded, first leaf with old tape closing tears (with some losses from inner and lower parts of that leaf, this damaging a few lines of text at base, and with small areas of damage to bottom of next few leaves), else good and presentable condition, 212 by 145mm.; nineteenth-century parchment over pasteboards, marbled endleaves, with “94 / MS / Plinio et altri / 00 / 27” in ink on spine Provenance: 1. Written by the scribe Laurentius Capitaneus, who names himself in colophons on fol. 98v and 164r, the first identifying him as a notary of Perugia (“perusini notarius”) and dating the completion of this part of the work to 1460, the second identifying him as a monk (“monachus”), and dating its completion to “1461 KL Februarii”.2. In the library of an Italian community dedicated to St. Maurus of Rome: their eighteenth-century ex libris at head of frontispiece.3. Joseph Sarughi: his ex libris dated 1814, noting that he was a priest, on endleaf opposite frontispiece. Text: This volume is a compendium of rare humanist texts, apparently copied for a monastic readership. It opens with a De viris illustribus text (fols. 1r-26r), that chronicles the lives of important Romans. The text has been attributed in the Renaissance to both Pliny the younger (61-c. 113 AD.) and his elder namesake (as here at head of fol. 1r), as well as Suetonius (c. 69-122 AD.) and Cornelius Nepos (c. 110-25 BC.). From the sixteenth century onwards, following the advent of printing, it was most commonly connected to the author Sextus Aurelius Victor (c. 320-90). All of these attributions have been rejected by modern scholarship, but the work was certainly of the Ancient World and most probably a product of the fourth century (see M.M. Sage, ‘The De Viris Illustribus: authorship and date’, Hermes 108, 1980, pp. 83-100.). The De viris illustribus tradition was a popular Roman literary genre, which may have begun in the circle of Cicero, with the oldest surviving examples being Cornelius Nepos’, Liber De Excellentibus Ducibus Gentium (Lives of Eminent Commanders), and Suetonius’ fragmentary De Viris text. It rose to its height in the Ancient World with Jerome’s work of that name, and the continuation of that, but then was set side as a genre until the Renaissance. The work here is the longer version of this text, not commonly found in manuscript but well represented among early printed witnesses, opening with a chapter on King Procas of Alba Longa, the mythological great-grandfather of Romulus and Remus. Manuscripts of the text (in any version) are rare on the market. This is followed by the lengthy commentary of the First Punic War, the first of the three major wars between the Roman Empire and Carthage in 264-241 BC., by Leonardo Bruni (c. 1370-1444; here fols. 28r-98v), probably the most important Humanist historian of the Italian Renaissance. He was the pupil of the grand humanist, Coluccio Salutati, whom he succeeded as chancellor of Florence, and before that served as apostolic secretary to four popes. This work is based on that of the Greek historian Polybius, and fascinatingly (and perhaps even bizarrely) it attempts to fill a gap that the humanists saw in their sources. It is a rearranging of the available Greek accounts to produce a Latin work that tells the story of the First Punic War from the Roman perspective, andthus fills the void left by the missing second decade of Livy’s history. It is part compilation and part invention, manufacturing a source that many Renaissance readers wanted to read, but did not survive. It has been unkindly described as a translation of parts of book I of Polybius, but is much more, drawing on Strabo, Thucydides, Florus, and Plutarch. Again manuscripts on the open market are far from common in the last few decades, and only four have appeared on the open market since 1950. The volume continues with a text on Aesop, opening “Esopus ille e Phrigia fabulator haud immerito …”, which is also recorded in Venice, Marciana, lat. II 123 (10,383) (Kristeller, Iter Italicum, II, 1967, p. 251; here on fols. 99r-121v), and a copy of Cicero, De senectute (fols. 121v-135v). It ends with a series of Christian lives of Desert Fathers by Jerome (fols. 136r-188v): the Vita Malchi monachi captivi, the Vita Pauli heremitae, the Vita Hilarionis and the Vita Athanasii, which were popular monastic texts throughout the Middle Ages. These are interspersed with some letters of Jerome concerning the clerical and monastic life (fols. 164v-178v). A hand of the seventeenth century has added a contents list on the last leaf of the codex, noting that part of the Vita Hilarionis on fol. 155v concerns the race of Saracens, who were “devoted to the devil”. Ɵ Indicates that the lot is subject to buyer’s premium of 24% exclusive of VAT (0% VAT).