A pair of Sitzendorf attributed porcelain dressing table mirrors, 20th century, each mounted with two cherubs with either pink or blue drapes above a floral encrusted mirror with gilt feet and with easel support. 30 cm x 22 cm. CONDITION REPORT: Both mirrors have wooden backs. We cannot therefore see any back stamps without removing the back which we would rather not do. Both mirror frames are in generally extremely good condition. We cannot see any evidence of any repairs or restoration. The floral encrustations do not have any significant losses. There maybe the odd very minor chip. All in all the condition is really extremely good.

We found 30757 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 30757 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

30757 item(s)/page

An Art Deco white gold diamond set bar brooch, c.1925, with an old European cut diamond, milligrain set to a box collet at the centre. A flat section, tapered bar to each side, milligrain set with graduated old European cut diamonds to a chenier gallery, 'C' catch and fold-down safety easel. Marked 18ct. 70 x 57mm, 5.70g

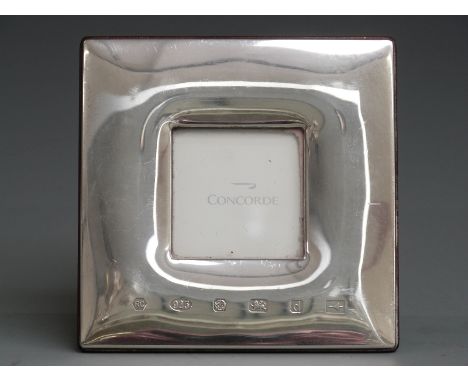

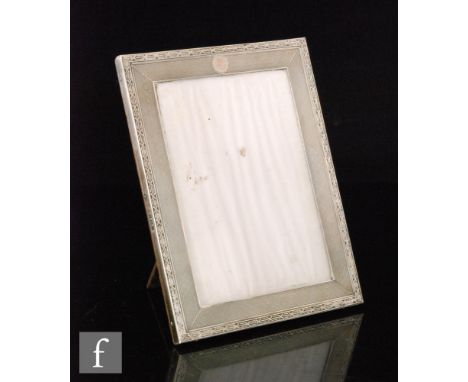

A contemporary silver rectangular photograph frame, by Whitehill Silver & Plate Co, assayed Sheffield 1992, having arched top with bow and festoons, felt lined easel back, height 24.2cm x width 16.4cm, together with another contemporary silver rectangular photograph frame, by Carr's of Sheffield Ltd, assayed Sheffield 1992, embossed with pairs of hearts to corners and with easel back, height 22.2cm x width 17.3cm, and a third contemporary silver rectangular photograph frame, by Gordon & Christopher Kitney, assayed London 1993, with ribbed border, height 21.4cm x width 16.3cm. (3)

Boxes & Objects - an early 20th century French artists box, hinged cover printed with a musician and his beau, lyre shaped easel to interior, single drawer to side holding water colours; a 19th century treen gavel; 19th century Swiss musical box, decorative transfer printed cover of a young lady amongst the woodland with her dog; another music box; counter bell; etc

S. T. Dupont, A dual time travel alarm clock, quartz movement, 24 hour dial, second dial with Roman numerals and alarm indicator hand, easel back, 60mm diameter; and Seiko, a desk alarm clock, quartz mechanical movement, dot markers, spade hands, centre seconds and alarm indicator hands, engraved with presentation inscription, 81mm wide

* KUSTODIEV, BORIS (1878–1927) Bakhchisarai, signed and dated 1917.Oil on canvas, 80.5 by 94 cm.Provenance: Collection of N.D. Andersen, Leningrad.Acquired by the grandfather of a previous owner.Private collection, UK.Authenticity of the work has been confirmed by the expert V. Petrov.Exhibited: Mir Iskusstva, Petrograd, 1918.Boris Mikhailovich Kustodiev, State Russian Museum, Leningrad, 1959.Literature: Exhibition catalogue Mir Iskusstva, St Petersburg, 1918, p. 9, No. 174, listed.V. Voinov, B.M. Kustodiev, Leningrad, Gosudarstvennoe izdatelstvo, 1925, p. 84, listed under the works from 1917.Exhibition catalogue, Kustodiev, Leningrad, 1959, p. 37, listed under the works from 1917.M. Etkind, Boris Mikhailovich Kustodiev, Leningrad, Iskusstvo, 1960, p. 197, listed under the works from 1915, marked as completed in 1917.M. Etkind, Boris Kustodiev, Moscow, Sovetskii khudozhnik, 1982, p. 178, listed under the works from 1917.Related literature: For a study for the present work, see Gosudarstvennaia kartinnaia galereia Armenii. Zhivopis. Skulptura. Risunok. Teatr. Katalog, Yerevan, Aiastan, 1965, p. 502, listed as Prodavtsy fruktov. Bakhchisarai.Boris Kustodiev’s painting Bakhchisarai, offered here for auction, is a unique work in the artist’s legacy. Among his classic easel works, it stands out because of its unexpected Oriental subject, which is more reminiscent of a stage set than the canvasses typically associated with the artist; and also because of the precise geographical siting of the motif and the vibrant range of colours in the night landscape — a palette that is unusual even for Kustodiev.In 1915, the artist spent two months in the Crimea, but, through a combination of circumstances, Bakhchisarai is now the only reminder of this trip. Perhaps this is because the journey to the Crimea was something that the artist needed, rather than wanted, to do. Kustodiev’s spinal illness was growing progressively worse, and he urgently required a change of climate; he also wanted to try a medicinal mud treatment. In a letter to the art historian and collector Fyodor Notgaft dated 2 September 1915, he complained: “I came to Moscow, and soon I have to leave it again — the doctors insist, and I feel it myself, since my health is very, very poor.... I’m going to Simferopol on the 11th, and from there on to Yalta. I’ll be in a clinic there for 2 weeks, and then I’ll be living near Yalta for about a month and a half...” (B.M. Kustodiev. Pisma, statii, zametki, interviu, Leningrad, Khudozhnik RSFSR, 1967, p. 151).We know very little about the artist’s stay in the Crimea. More precisely, we know only the scant details that he revealed to his relatives and friends in letters. At the beginning of October, Kustodiev writes from Yalta to his daughter Irina: “Mum and I have a large, very bright room facing south — there are poplars, palm trees, roses and pines in front of the windows — there are mountains in the distance. The windows are wide open all day, it’s very warm. At 4 o’clock, they treat me with black, rather foul-smelling mud, then I take a bath, after that I lie down for a while on the bed till dinner, which is at 7 o’clock in the evening. It is really rather boring here, and we can’t wait to leave...”The same sort of despondency — albeit even more acute due to the change in weather — can also be seen in a letter that Kustodiev sent a few days later to the actor Vasily Luzhsky: “I’m listless and depressed. I don’t want to do anything. Despite even the muchhyped warmth and sunshine here, it’s very dreary and boring. Now we barely see either of them, it’s cold, the sun comes out for about two hours in the morning, and almost the whole sky is covered in rain clouds.” Because of his bad mood and poor state of health, Kustodiev does little work in Yalta. He is dispirited because the mud therapy, on which the doctors had pinned their hopes, has not brought about any positive changes, and a week before his departure, planned for 22 October, he, seemingly reluctantly, blurts out in a letter to Luzhsky: “I won’t write about myself — everything’s the same or even seems worse....”It is likely, therefore, that the only artistic impression associated with the artist’s stay in the Crimea was a trip to Bakhchisarai. It is from there that he brought one small watercolour study. Today, this sheet, which has preserved the original composition showing the small square near the old palace of the Crimean Khan, where the fruit vendors have taken up their positions, is housed in the National Gallery of Armenia in Yerevan. The drawing was made from real life in the morning, when there was still no bright sunlight, and the sellers were just laying out their wares in the square among the small buildings of the ancient capital of the Crimean Khanate, surrounded by mountains. This study was used for the big picture, dated 1917, which Kustodiev executed when back in his studio in Petrograd.During work on the canvas, Kustodiev altered the sketch quite substantially. The central emphasis in the figural and dynamic structure of the picture is now not so much on the landscape but rather on the conveying of light and colours of an evening street in the little Tatar town. The composition boasts an abundance of characters and eloquent details that reveal the subject because of their convincingly realistic and authentic rendering. However, the groundwork for the structural design of the composition was undoubtedly laid by the watercolour sketch. The mountains encircle the space in the distance, so that the main action, devoid of any centre, takes place in what looks like a narrow stage setting, bounded by a backdrop of characteristic Oriental structures.The repeated horizontal divisions — the outlines of the gently sloping mountains and oblong roofs — contrast with the vertical forms of the minaret and the rising smoke from a furnace and, combined with the bustling crowd in the foreground, constitute the basis of a rhythm, the vibrant waves of which run through the market square, the diagonally diverging streets and the picture as a whole. The artist eschews any literal handling of real life and daringly creates the provocatively gaudy colour combination of an orange sunset sky, dark-blue shadows and the thin sickle of a moon, the cold light of which is offset by the blindingly hot light of the windows.As Kustodiev creates a universal image of “the east”, he is looking for a generalisation that is convincing because of specifically recognisable details and literal quotations from what he has seen in reality. He chooses to combine the impressions of what he has seen at different times of the day and in different places; yet it is not a chaotic, random and arbitrary mishmash, but a strictly organised whole. Unusual though it may be, Bakhchisarai undoubtedly fits into Kustodiev’s artistic system of the 1910s, in which the theme of the colourful street fair and street trading is prominent. From Village Bazaar (1903) and The Fair (1906) onwards, the persistent theme in Kustodiev’s work comes to be that of crowded and plentiful shopping squares, market days and Volga vegetable displays, which symbolise the inherent, natural wealth of the land and the fruitfulness of farm labour.

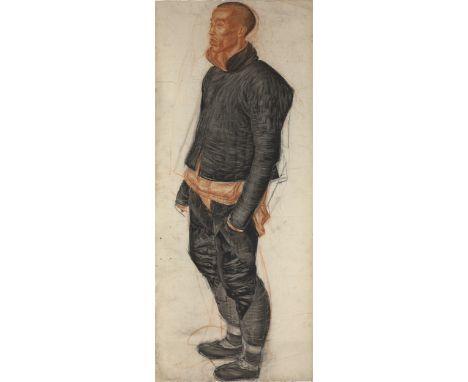

*YAKOVLEV, ALEXANDER (1887–1938) Portrait of a Chinese Man.Sanguine, charcoal and crayon on paper, laid on paper, 155 by 63.5 cm.Executed c. 1918. Provenance: Collection of the opera singer Alexandra Yakovleva (1889–1979), the artist’s sister. Acquired from the above by the previous owner in 1978 (inscription on the backing paper). Private collection, USA.Yakovlev, Portrait of Chinese Man: Exhibited: Possibly, Exhibition of works by Alexander Yakovlev, Gallery Barbazanges, Paris, April–May 1920. Possibly, Exhibition of works by Alexander Yakovlev, Grafton Gallery, London, May–June 1920.The graphic work Portrait of a Chinese Man, measuring one and a half metres in height, that is offered for auction is one of the very rare pictures that Alexander Yakovlev produced on such a scale, and it was created during his first Far Eastern journey in 1917–1919. The artist went to China, Mongolia and Japan on a scholarship from the Academy of Arts, but his impressions and encounters with unusual models and subjects so captivated him that, once the period of his study trip had expired, Yakovlev sought an opportunity to extend his stay in Asia. He visited temples and poor neighbourhoods in towns, accompanied camel drivers, went out to sea with fishermen, befriended pearl divers and attended festive ceremonies and burials. The natural landscapes, the human diversity, the distinctive character of the way of life, and the brightness of the national costumes and adornments struck the European’s imagination, and he ecstatically depicted actors at the traditional Chinese and Japanese theatres, Tibetan lamas, Imperial military leaders and Mongolian nomads. He brought back from the trip hundreds of sketches and easel drawings, executed in the most difficult field conditions. In a report to his professor at the Academy, Dmitry Kardovsky, about these wanderings, the artist declared: “China, Mongolia, Japan. Stages on the journey. Infinitely interesting countries... abundant images. Rich in colours. Fantastic in shapes. Strikingly diverse in culture. Different myths. More diverse than those that took root in our little Europe. I worked hard; life was often very lonely. Especially psychologically... A very difficult first year in Pekin without money or income... I had a stroke of luck when life became totally difficult. I arranged an exhibition in Shanghai, where I didn’t sell very much, but I got many commissions for portraits. That enabled me to pay off my debts and go on to Japan, where I spent an unforgettable summer on the island of ?shima.” These lines illustrate the importance of the series of full-length portraits when seen against the background of the exotic genre and landscape scenes. The work on offer is one of the most accomplished of them and is marked by skilful drawing, expressiveness and brilliant mastery of brushstrokes and lines when conveying the characteristic features of the figure and face. By blending academic clarity and exotic colouring, Yakovlev was able to create a stylised ethnic image that was both expressive and credible. Portrait of a Chinese Man is a finished easel piece, where the sharp characteristics of the model are conveyed with a meticulous authenticity that captures both the individual and the generalised, ethnic and historical features of the appearance of someone living in the Celestial Empire. According to the eminent critic Abram Efros, it is not a matter of chance that, since it was on his first Eastern journey that he emerged as an artist, Yakovlev forever “remained the same brilliant, academic, exotic personality, the Vereschagin of the 1920s – minus realism, plus decorativism....” At the review exhibition of the results of the trip, which the artist presented in 1920, first in Paris and then in London, the Chinese works were especially prominent. Public and critics alike enthusiastically hailed the works’ exotic authenticity and artistic mastery. Nicholas Roerich, who visited the exhibition in London and was himself infatuated at the time with the East, later recalled: “I remember Yakovlev’s 1920 exhibition in London: the large display rooms were filled with astonishing paintings from China. What a delicate and convincing power lay in them, yet at the same time there was no imitation; originality resonated everywhere." Authenticity of the work has been confirmed by the expert E. Yakovleva.

-

30757 item(s)/page