We found 1820 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 1820 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

1820 item(s)/page

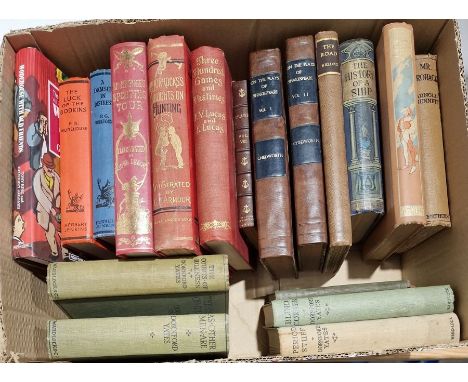

Box of assorted antiquarian and other good quality books to include 'Wales Illustrated in a series of views', 'Life, Travels & Reminisces of J Ceredig Davies' two editions of 'Aberystwyth & the Court Leet' by G Eyre Evans, 'Welsh Folk Law' by J Ceredig Davies, 'The History of Gruffydd Ap Cynan' by Arthur Jones, 'Houses of the Welsh Country Side' by P Smith, 'Cardigan Priory in the Olden Days' by Emily M Pritchard, various other topographical and historical books to do with Wales and other including Mitford 'History of Greece', 'Pepys' Diary', etc. (B.P. 21% + VAT)

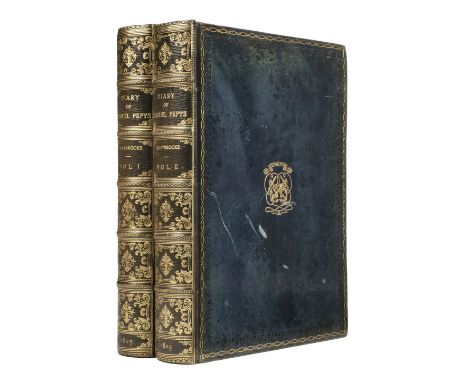

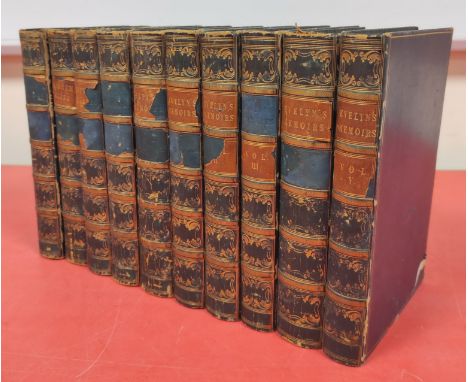

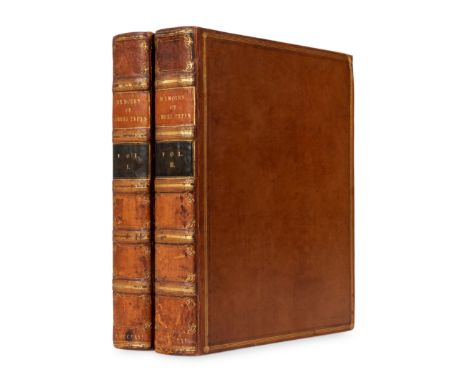

PEPYS, Samuel (1633-1703). Memoirs of Samuel Pepys. Comprising His Diary from 1659 to 1669. London: Henry Colburn, 1825. 2 volumes, 4to (299 x 225 mm). Half-titles, 13 engraved portraits and plates including one folding map, in-text illustrations, advertisement leaf in vol. I. (Some offsetting, spotting or staining). Contemporary calf gilt, spine in 6 compartments with 5 raised bands, brown and black lettering-pieces gilt, edges marbled (skillfully re-backed, some minor wear, a few light scuffs to sides); later beige cloth slip-case. Provenance: Hugh Percy, possibly (1785"“1847) 3rd Duke of Northumberland (bookplates).FIRST EDITION of Pepys' diary, which was in cipher until 1825, when it was deciphered by John Smith. Edited by Lord Braybrooke, the contents depict contemporary everyday life, making this a popular source of information about late 17-century England. Grolier English 75.Property from the Annette Perlman Trust

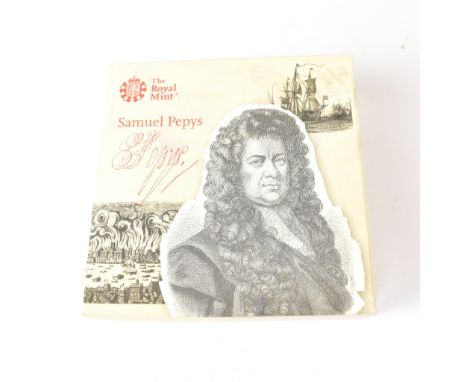

CHANGE CHECKER; an album containing various Change Checker packet uncirculated coins, mostly crowns, to include a Keys and Lantern Tower of London coin, Tower of London Beefeater £5 coin, Tower of London Raven £5 coin, Tower of London Crown £5 coin (x2), Yale of Beaufort 2019 £5 coin, Elizabeth II 2019 Queen Victoria commemorative £5 coin, Queen Mother 1980 crown, Elizabeth and Philip 1972 crown, various £2 coins, some possibly circulated, to include the Wedgwood £2, Samuel Pepys, D-Day 75th Anniversary 2019, Britannia 2015, 1996 World Cup, the Fire of London, a Charles & Diana crown and a Silver Jubilee crown, also various loose coins in packets, to include £5 coins, commemorative coins, Churchill commemorative coins, etc.

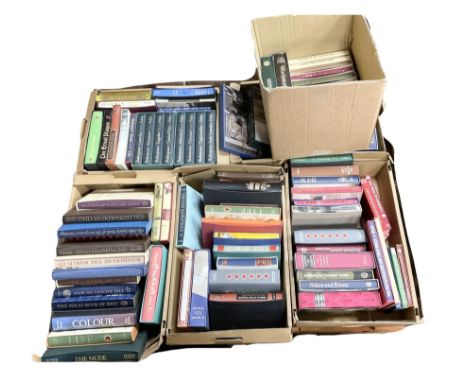

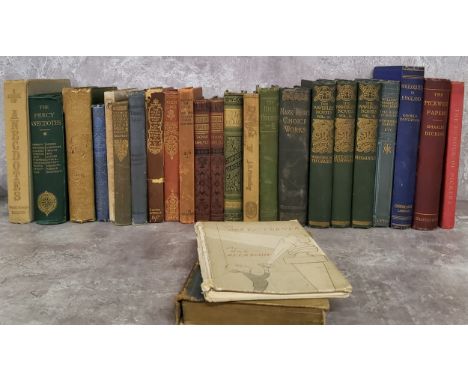

Books - English Literature - a collection of Victorian and Edwardian works, some later, including a body of works by Samuel Pepys; Bernard Shaw; volumes of work by Ruskin; Montaigne's essays; Waverley novels; other classics; A concise and comprehensive grammar of the English tongue, Fenning's Dictionary 1761, leather bound, marbled hard board binding; Macdonnel, D.E: A Dictionary of quotations, in most frequent use, tak[...] 1822; Beeton's Dictionary of Universal Biography, Portraits, published by Ward, Lock & Co.; etc qty qty (6 boxes)

Peter Monamy (London 1681-1749)The venerable HMS Eagle making ready to sail from her offshore anchorage, probably at the Nore oil on canvas83 x 122.5cm (32 11/16 x 48 1/4in).Footnotes:ProvenanceAdmiral Sir John Peter Lorne Reid GCB CVO (1903-1973), Bolton.Private collection, UK.Whilst not a retrospective in the accepted sense, this work depicts an elderly 3rd rate, a vessel seemingly from an earlier age, past her prime and in her twilight years. The overly high stern, in conjunction with the elegant side windows of her stern galleries, are both features more typical of the ships-of-war dating to the reign of Charles II and the navy of Samuel Pepys during his hugely influential tenure as Chief Secretary to the Admiralty. Notwithstanding her outward appearance however, the vessel is clearly flying the new 'Red Ensign' introduced into the fleet after the Act of Union with Scotland in 1707 and which alone confirms her longevity. Almost certainly one of Pepys's celebrated 'Thirty Ship Programme' of 1677, a surprisingly large number of those ships (built between 1678 and 1680) were still in service in 1707, although by then all of them would have been altered, repaired or, in some cases, completely rebuilt to reflect the continual ravages of the sea, battle damage or to incorporate periodic changes in armament. As the largest 'class' within the 1677 Programme, the twenty 3rd rates - of which Eagle was one - have since been described by some naval historians as 'the best-looking sailing ships ever completed', but attempting to name a specific vessel within the twenty is complicated by the fact that 'the individual ship design was in each case left to the builder.'It is usual to identify these majestic ships by a careful study of their highly ornate stern carvings which usually include either royal ciphers, regal initials, or other similarly characteristic details. Unfortunately, this handsome bow view robs us of those clues although the distinctive side panes of the stern gallery windows shown here are strikingly similar to those featured on the splendid but short-lived Coronation, a large 2nd rate launched at Portsmouth in 1685. It is interesting to speculate therefore that this vessel might also be a Portsmouth-built ship which narrows the field considerably and offers up two possibilities, namely the Eagle and the Expedition. Of the two, the more likely candidate is the Eagle which, having been repaired and reconditioned at Chatham in 1699-1700, then served with distinction during the War of the Spanish Succession, mostly in the Mediterranean, and was part of Sir George Rooke's fleet which famously took Gibraltar in 1704. By 1707, Eagle was in Sir Cloudesley Shovell's squadron in the Mediterranean which, whilst returning home for the winter, was wrecked on the Isles of Scilly on 22nd October that year due to faulty navigation. This error resulted in one of the most spectacular disasters in the long history of the Royal Navy and this painting may well be a memorial to the loss of a fine old ship and all those who perished in her.Peter Monamy was born in London in 1681, the youngest son of a Guernsey man. Throughout his career he was heavily influenced by the works of Willem van de Velde, the Younger and other North European, Dutch and French masters. Monamy was himself a collector of Van de Velde's drawings and these influenced his development as a maritime painter resulting in numerous commissions from mercantile and naval patrons, including the famous Channel Island's naval families, the Durrels and the Saumarezs. In 1726, he was elected a Liveryman of the Company of Painter-Stainers, to which he presented a very large painting of the 'Royal Sovereign at anchor' which still remains in their collection. Although his paintings usually depict actual ships, they rarely record specific events as, up until 1739, his career coincided with a long period of peace. From the 1730s until his death, Monamy was at the centre of London's artistic life and was a friend and companion of Hogarth, sometimes collaborating with the celebrated younger artist. Despite his many commissions however, he was never particularly prosperous and also painted decorative pictures specifically for commercial galleries and dealersFor further information on this lot please visit Bonhams.com

Boon, G.C., Welsh Tokens of the 17th Century, Cardiff, 1973, 144pp, illustrations in text, 1976 Supplement tipped-in (Manville 1269); Berry, G., Taverns and Tokens of Pepys’ London, London, 1978, 144pp, illustrations in text (Manville 1378); Todd, N.B., Tavern Tokens in Wales, Cardiff, 1980, xxv + 236pp, illustrations in text, signed by George Boon (Manville 1439); Whitmore, J., Worcestershire Inn Tokens, Malvern, 1988, 220pp, illustrations in text, copy no. 3, signed by the author to Denis Vorley (Manville 1640); together with other references on tokens (14), by Bell, Seaby, Kelly, Scott, Williams, etc [18]. Publishers’ bindings £50-£70 --- Provenance: Ex libris Alan Morris

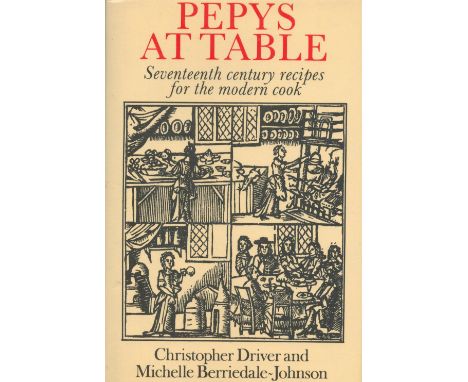

Pepys At Table Seventeenth Century Recipes for the Modern Cook by C Driver and M B Johnson Hardback Book 1984 First Edition published by Bell and Hyman Ltd some ageing good condition. Sold on behalf of the Michael Sobell Cancer Charity. We combine postage on multiple winning lots and can ship worldwide. UK postage from £4.99, EU from £6.99, Rest of World from £8.99

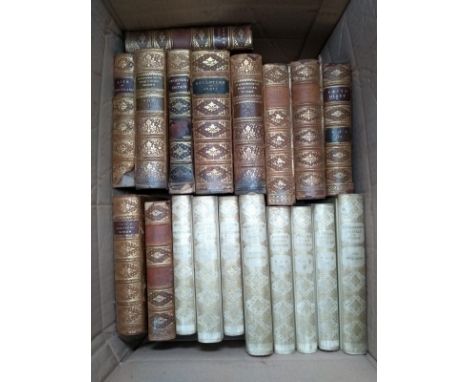

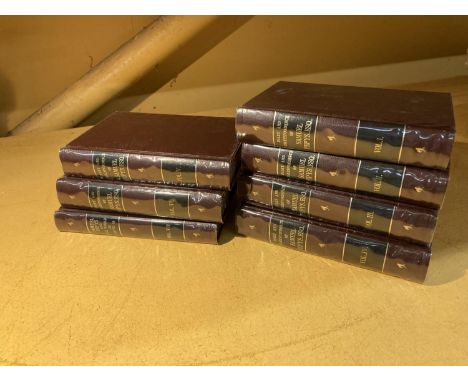

Reiman (Donald H. [editor]). Shelly and his Circle 1773-1822 [The Carl H. Pforzheimer Library, volumes 7-8], 2 volumes, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986, monochrome illustrations, publishers uniform original red cloth in slipcase, large 8vo, together with;Fehrenbach (R. J. [editor]), Private Libraries in Renaissance England, a collection and catalogue of Tudir and Early Stewart book-lists [Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies], 6 volumes, Binghamton: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1992-2004, previous owner inscriptions to the front endpapers, publishers uniform original blue cloth, 8vo, plus, Latham (Robert [editor]), Catalogue of the Pepys Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge, 5 volumes, facsimile edition, Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1987, numerous black & white facsimile pages, publishers original uniform black cloth, large 4to, and other modern & scholarly bibliography & libraries reference & related, including Short-Title Catalogue of books printed in England,..., 1641-1700, 4 volumes, by Donald Wing, New York: The Modern Language Association of America, large 4to, & A History of Russian Hand Paper-Mills and their Watermarks, by Zoya Vadil'Evna Uchastkina, Hilversum: The Paper Publications Society, 1962, folio, mostly original cloth, some in dustjackets, G/VG, 8vo/folio Qty: (3 shelves )

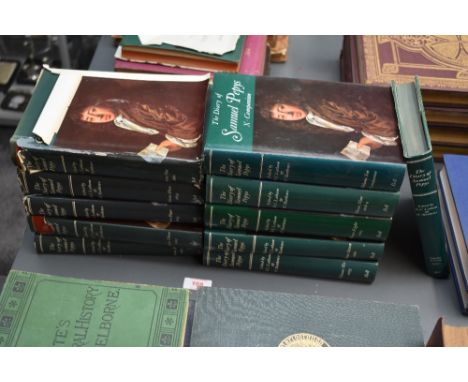

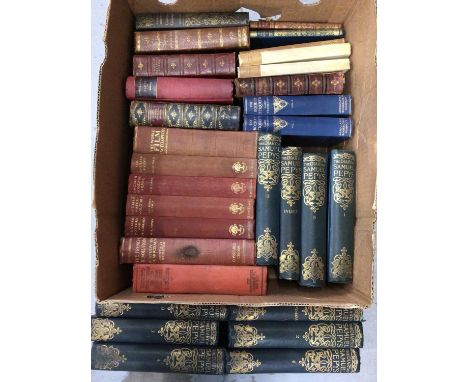

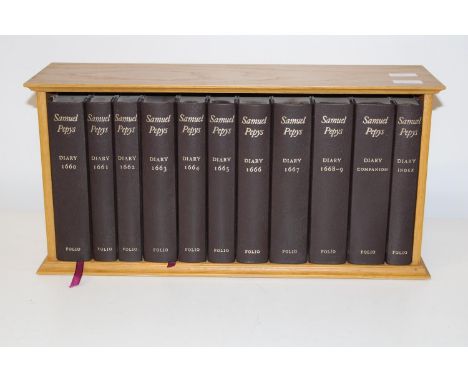

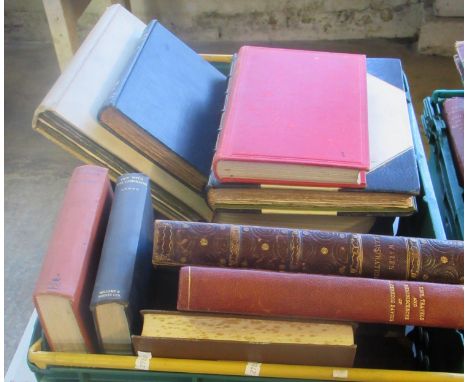

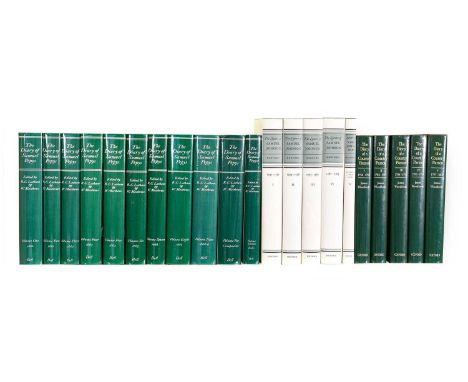

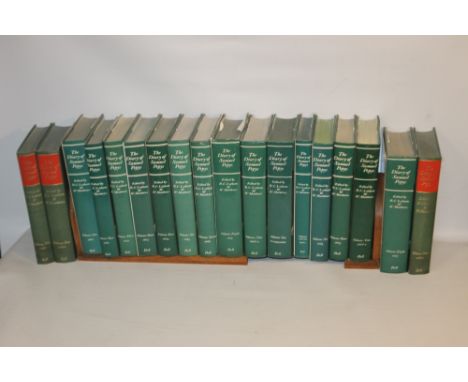

Assorted volumes to include Fletcher Bannister "A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method", Batsford 1950, photographic illustrations, plans and dreawings, Please note the Pepys volumes are with drawn and will be in the book sale June 7th Volumes of the Diary of Samuel Pepys, G, Bell & Sons 1910, Vols 2, 5, 7 and the Index only, Braybrooke Lord "The Diary Samuel Pepys" Vol 1 only, Samuel Pepys Letters and The Second Diary 1656 and 1703, James Dent & Sons, Uniform with "The Travels of Marco Polo The Venetian", J.M. Dent & Sons, Weekly, Henry B "Samuel Pepys and the World he lived in", Gilbert, W.S. "The Savoy Operas", MacMillan & Co. 1932, "The Bab Ballads" 1930, blue cloth with gilt decorations and titles, Escoffier, August "Ma Cuisine", Paul Hamlyn, "King Albert's Book", Reverend George Crabb - Life and Poems of ..., Volume 8 only, published John Murray 1834, rebound, half Morocco, gilt titles and raised bands, Seymour E.H. "Remarks Critical Conjectural and Explanatory upon the Plays of Shakespeare..." London, printed Wright 1805, rebound half Morocco contemporary boards laid down, appear to be varnished, and various other volumes ( Please note the Dornford Yates books also with drawn/(2 boxes)

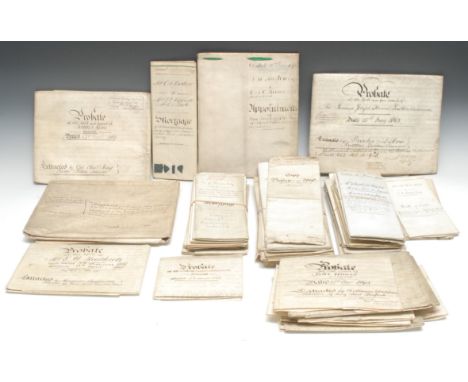

Legal History - an interesting collection of deeds and indentures, c.1720-1934, including a vellum probate grant dated 1866; a presentation to the vicarage of Offchurch, Warw. by Lord and Lady Guernsey as patrons to Henry (Pepys), Bishop of Worcester on behalf of Revd. John Wise, MA 28th June 1850; partnership articles relating to Messrs. Jackson, Ruston & Keeson, publishers, 3/6/1926; marriage settlement relating to the forthcoming wedding of George Short of East Keale, Lincs and Penelope Tirwhitt [sic], elder daughter of Sir John Tyrwhitt, Bt., 22/10/1720; deeds relating to trusts; a quantity of wills 1858-1934 (13 on parchment, 5 on paper), notably that of Mrs,. E. U. Heathcote, wife of Unwin Heathcote of Sephalbury, Herts., in favour of her brothers Money and Loftus Wigram 5/32/1858, pr. 11/4/1861)and a written valuation of £12,799 in respect of the estate of Scott’s Hall, Rochford, Essex consisting of a house and 404 acres, 1857.*Heneage Finch, by courtesy Lord Guernsey, was the eldest son and heir of 5th Earl of Aylesford (whom he succeeded as 6th Earl in 1859 and died in 1871); the formal patron of Offchurch was Lord Guernsey’s wife, Jane, daughter and heiress of John Whitwick Knightley of Offchurch Bury, who died in 1911.*Jackson, Ruston & Keeson were formed in the later 19thcentury and were publishers of directories and other works of reference.*Sir John Tyrwhitt of Stainfield, Lincs. 5th Bt. (1663-1741) was Whig MP for Lincoln 1715-1734; the marriage did indeed go ahead later in that year; Penelope Short was a co-heiress to her brother, Sir John, 6th Bt. who died in 1760.* Money Wigram (1790-1873) and Loftus Wigram QC, MP (1803-1889) were second and seventh sons respectively of the Irish East India magnate, Sir Robert Wigram MP 1st Bt. by his second marriage.

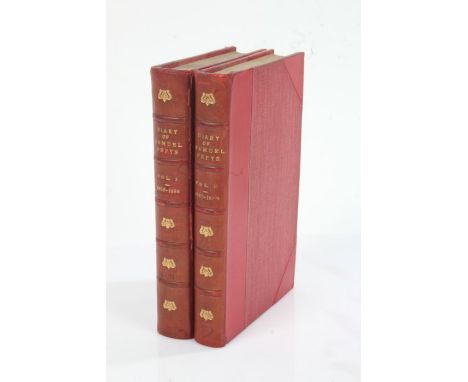

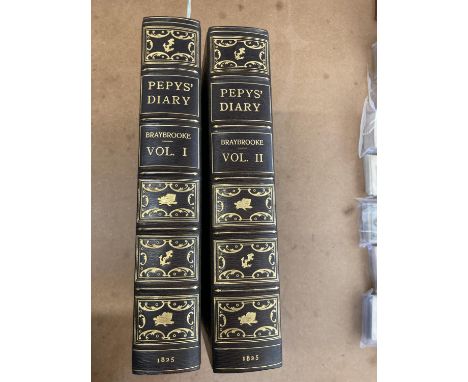

Pepys, Samuel. Memoirs of Samuel Pepys, Esq., F.R.S.... edited by Richard, Lord Braybrooke, 2 volumes, first edition, half-titles, 13 engraved plates, including one double-page plan, EXTRA-ILLUSTRATED with a further 62 engraved portraits and views, some laid to size, a few hand-coloured, nineteenth century straight-grained full morocco by Bayntun Riviere, tooled elaborately gilt, the covers with Pepy's motto blocked in gilt, all edges gilt, 4to, London: Henry Colburn, 1825

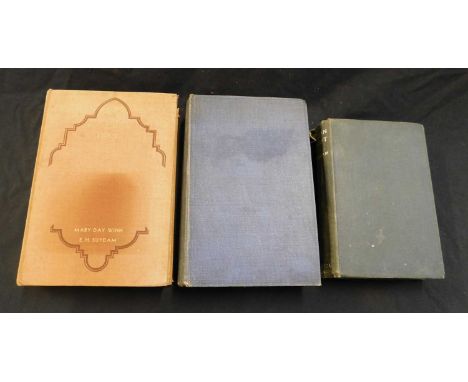

MARK PEPYS, 6TH EARL OF COTTENHAM: SICILIAN CIRCUIT, London, Cassell, 1933, 1st edition, contemporary inscription on front paste down, original cloth worn and soiled, split at head of spine + MARY DAY WINN: THE MACADAM TRAIL, TEN THOUSAND MILES BY MOTOR COACH, ill Edward Howard Suydam, New York, Alfred A Knopf, 1931, 1st edition, coloured frontis, 32 black and white plates as list, original cloth gilt + INGLIS SHELDON-WILLIAMS: A DAWDLE IN FRANCE, London, A & C Black, 1926, 1st edition, inscription on ffep, original cloth gilt (3)

Braybrooke (Richard). Diary of Samuel Pepys, London: Henry Colburn, 1825, half-titles, frontispieces, 10 engraved plates, folding map, turn-ins finished in gilt, marbled endpapers and pastedowns, bookplates to front pastedowns, hinges repaired, lightly spotted, 19th-century blue morocco gilt, spine in 6 compartments separated by raised bands finished in gilt, 4 compartments incorporating gilt floral tools, 2 with gilt directs, compartments bordered in gilt, boards with oval gilt border, gilt armorial vignettes to centre of boards, extremities slightly rubbed, boards marked, folioQty: (2)

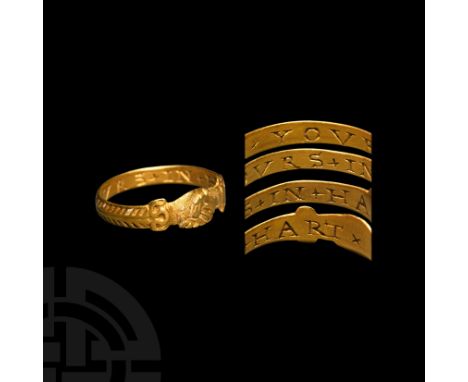

16th-early 17th century AD. A gold annular D-section fede band with bezel formed as two hands engaged in a handshake, emerging from decorative cuffed sleeves, medial line engraved around the hoop, with diagonal dashed recesses above and below, the top band leaning right, the bottom leaning left, remains of enamelling; the interior inscribed: ' x YOVRS + IN + HART x ' in Roman capitals. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.111, for this inscription in italics, sourced in a book believed commonplace in c.1596; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database id. SUSS-C86B41, for a ring with the same posie in the same script, dated c.1596-1650 AD; cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.411, for a similar style ring dated 16th-17th century. 1.48 grams, 17.31mm overall, 15.75mm internal diameter (approximate size British H 1/2, USA 4, Europe 6.81, Japan 6) (3/4"). UK antiques market between 1974-1985. From the Albert Ward collection (part 2), Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] Fine condition.

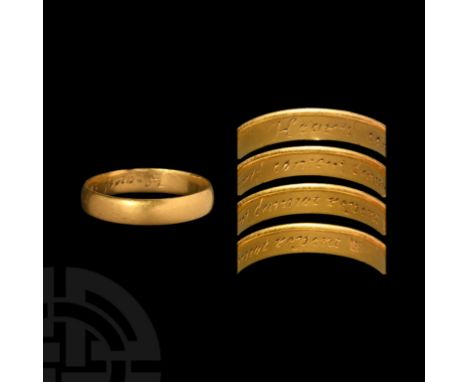

17th-18th century AD. A substantial gold D-section annular band with plain exterior, the internal face inscribed 'Hearts content cannot repent', followed by maker's mark 'B' in worn cartouche. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, pp.46-47, for this inscription and variations; cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.78, for a similar ring with this inscription, dated 17th century. 4.65 grams, 22.50mm overall, 19.50mm internal diameter (approximate size British T, USA 9 1/2, Europe 21.26, Japan 20) (1"). UK antiques market between 1974-1985. From the Albert Ward collection (part 2), Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Some sources suggest that rings were acquired ready- engraved, and that they may have been engraved sometime after their initial production and by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] Fine condition, some wear. A large wearable size.

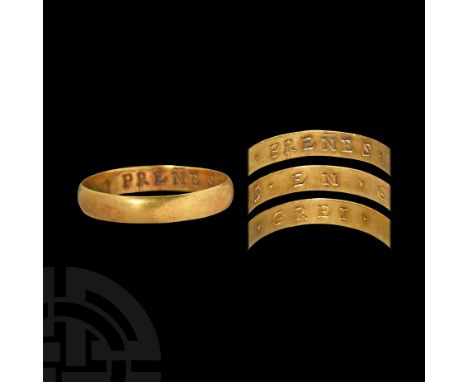

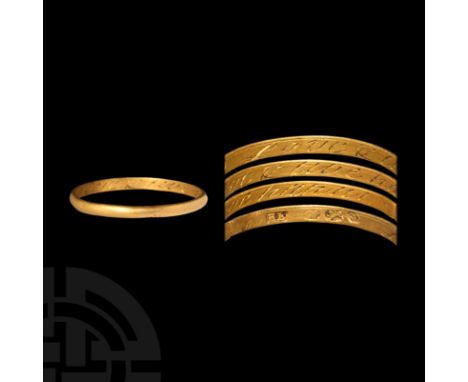

16th-17th century AD. A gold D-section annular band with plain exterior, the interior with French inscription ' . . PRENES . EN . GREI .', The Anglo-Norman Dictionary glosses the phrasal verb 'prendre en gre' as 'to accept as a favour'; here we may translate 'graciously accept [this]', the phrase is conventional, part of the idiom of amour courtois, and found inscribed on various types of love-gift, often continuing, 'ce petit don' [this little gift]. Cf. Joan, E., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, p.43, for this inscription, minus the final 'I'; cf. The British Museum, museum number 2002,0501.1, for a ring with a very similar inscription and script dated 16th-17th century AD; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. KENT-B71606, and PAS-3785E3, for rings with very similar inscriptions, dated 16th-17th century AD. 2.00 grams, 19.24mm overall, 17.40mm internal diameter (approximate size British N 1/2, USA 6 3/4, Europe 14.35, Japan 13) (3/4"). UK antiques market between 1974-1985. From the Albert Ward collection (part 2), Essex, UK. The miscellaneous love-token uses of the phrase include a late 15th century boxwood comb in the BM, another formerly in the Londesborough Collection, a medieval ivory mirror case in the Metropolitan Museum, New York, an early 16th century enamelled plaque now in the Historisches Museum, Basel, a pair of salt-cellars enamel-painted by Pierre Reymond c.1550, and a 15th century brass knife-handle now in the Victoria & Albert Museum. A manuscript of The Erle of Tolous written in the 1520s [Oxford, Bodleian, MS Ashmole 45 Part 1, f.2r.] includes a full-page presentation frontispiece depicting a well-dressed young man near a speech scroll that bears the phrase as PRENES: ENGRE, as he proffers a book (the manuscript itself) to a young woman. The fashion for using the phrase in amatory inscriptions seems not to have survived the 16th century, making that century the best estimate for dating this ring. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] Very fine condition.

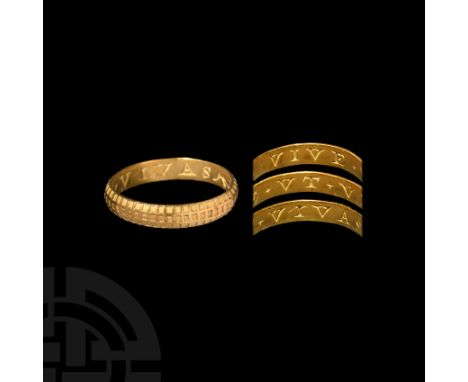

16th-early 17th century AD. A gold D-section annular band bearing three circumferential rows of shallow square cells on the external face, probably once enamelled, the inner face inscribed in Latin: 'VIVE + VT + VIVAS ' in Roman capitals, meaning 'live that you may live', given to convey the sentiment 'live life to the full', followed by a slender sprig. Cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. KENT-1F5049, for this inscription, dated 1550-1625 AD; cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1337, for this ring type, dated 16th century AD. 1.76 grams, 17.47mm overall, 15.30mm internal diameter (approximate size British H 1/2, USA 4, Europe 6.81, Japan 6) (3/4"). UK antiques market between 1974-1985. From the Albert Ward collection (part 2), Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] Very fine condition.

17th-18th century AD. A slender gold D-section annular band with plain external face, the interior inscribed 'Love & live happy', followed by maker's mark 'HB' in a rectangular cartouche, possibly for goldsmith Henry Burdett, followed by a sovereign's head, lion and 'S'. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.72, for this inscription; cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1331, for a similar ring and this inscription, dated 17th-18th century. 1.03 grams, 19.07mm overall, 16.88mm internal diameter (approximate size British N, USA 6 1/2, Europe 13.72, Japan 13`) (3/4"). UK antiques market between 1974-1985. From the Albert Ward collection (part 2), Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Some sources suggest that rings were acquired ready- engraved, and that they may have been engraved sometime after their initial production and by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] Fine condition.

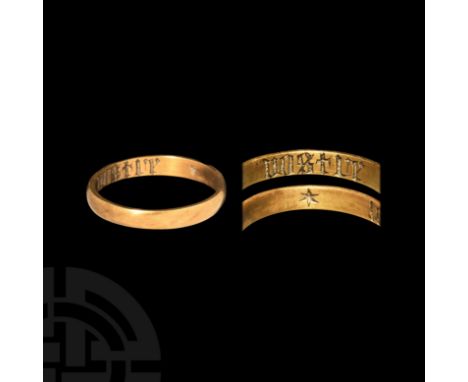

14th-15th century AD. A gold D-section annular band with plain external face, the internal face with Anglo-French inscription 'le [star] vostre [star star]' in blackletter script; the most obvious translation is 'yours', but the phrase le vostre is listed separately in the Anglo-Norman Dictionary in a quasi-legal sense which the Dictionary defines as 'your property'; in the feudal tradition of amour courtois, in wearing the ring, the wearer is acknowledging his/her humble status as a chattel belonging to the giver. 1.86 grams, 17.91mm overall, 16.07mm internal diameter (approximate size British K 1/2, USA 5 1/2, Europe 10.58, Japan 10) (3/4"). UK antiques market between 1974-1985. From the Albert Ward collection (part 2), Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Some sources suggest that rings were acquired ready- engraved, and that they may have been engraved sometime after their initial production and by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] Very fine condition.

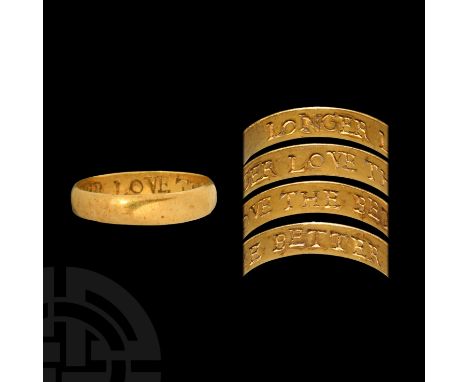

16th-18th century AD. A gold D-section annular band with plain exterior, the interior inscribed 'LONGER LOVE THE BETTER'. 1.91 grams, 17.49mm overall, 15.70mm internal diameter (approximate size British I 1/2, USA 4 1/2, Europe 8.07, Japan 7) (3/4"). UK antiques market between 1974-1985. From the Albert Ward collection (part 2), Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] Very fine condition.

c.18th century AD. A good size gold D-section annular band with plain exterior, the interior inscribed 'Godly love will not remove', followed by maker's mark 'JK' in rectangular cartouche. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, p.43, for this inscription; cf. The British Museum, museum numbers AF.1252 and AF.1253, for this inscription on a ring dated 17th-18th century AD, and museum number AF.1315 for this maker's mark, believed active between 1755-1764, name unknown; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. SUSS-73E152, for a similar ring with this inscription, also stamped 'JK', dated 1700-1800, possibly the same maker's mark. 4.18 grams, 21.50mm overall, 19.00mm internal diameter (approximate size British R, USA 8 1/2, Europe 18 3/4, Japan 18) (1"). UK antiques market between 1974-1985. From the Albert Ward collection (part 2), Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] Fine condition, a few knocks. A large wearable size.

17th-18th century AD. A heavy gold D-section annular band with plain exterior, interior inscribed 'Be Loveing and faithfull' [sic], two 'S' stamps in shield-shaped cartouches. See Evans, J, English Posies ad Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.25, for a variation on this posie; cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.8, for a script with similar double-barred letter 'B', dated 18th century. 6.07 grams, 22.40mm overall, 19.26mm internal diameter (approximate size British R 1/2, USA 8 3/4, Europe 19.38, Japan 18) (1"). UK antiques market between 1974-1985. From the Albert Ward collection (part 2), Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] Fine condition, some wear. A large wearable size.

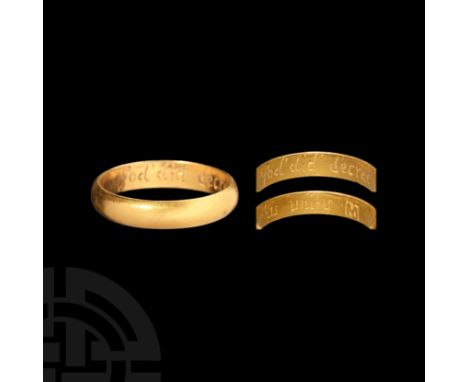

17th-18th century AD. A gold D-section annular band with plain exterior, the interior inscribed 'God did decree this unity', followed by a stamped maker's mark 'M' in an M-shaped cartouche. Cf. Joan, E., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.40, for this inscription with a slightly different spelling; cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1245, for a similar ring with slight variation on this inscription, dated 17th-18th century. 4.68 grams, 21.53mm overall, 18.82mm internal diameter (approximate size British Q 1/2, USA 8 1/4, Europe 18.12, Japan 17) (1"). UK antiques market between 1974-1985. From the Albert Ward collection (part 2), Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] Very fine condition. A large wearable size.

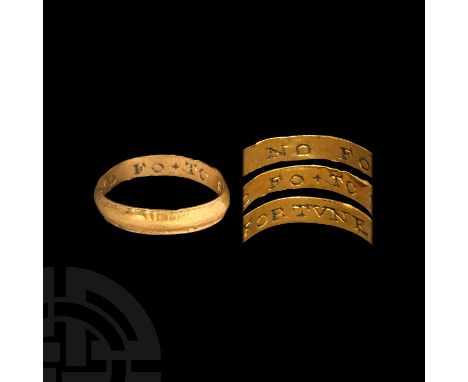

16th-17th century AD. A gold D-section annular band with slender collars around both edges, the internal face inscribed 'NO FO + TO FORTVNE'. See The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. NMS-5B55DC, for a similar ring and script, dated 1550-1650. 1.39 grams, 16.55mm overall, 14.57mm internal diameter (approximate size British G 1/2, USA 3 1/2, Europe 5.55, Japan 5) (3/4"). UK antiques market between 1974-1985. From the Albert Ward collection (part 2), Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] Fine condition, some wear.

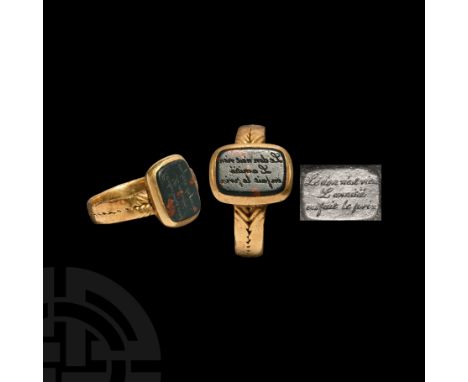

17th-19th century AD. A gold posy seal ring with D-section hoop engraved with a medial band of geometric motifs, expanding at the shoulders, rounded rectangular bezel, slightly concave on the underside, set with a red and green jasper stone inscribed in French: 'Le don n'est rien l'amitié enfait le prix' (reversed) in three lines, literally: 'The gift is nothing friendship is the price'; accompanied by a museum-quality impression. See Rey, M., Friendship in the Renaissance, Italy, France, England, 1450-1650, European University Institute, Florence, for discussion; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. DENO-B87439, for a ring with comparable hoop and shoulder decoration, dated 1600-1650. 3.22 grams, 21.11mm overall, 17.95mm internal diameter (approximate size British N 1/2, USA 6 3/4, Europe 14.35, Japan 13) (1"). UK antiques market between 1974-1985. From the Albert Ward collection (part 2), Essex, UK. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’, with posy rings being named thus in the mid 19th century. Prior to this date, there was no specific term for these rings, although there is reference to posies as jewellery in Shakespeare. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] Fine condition.

A mixed box of good hardback books many in full leather bindings to include Pepys' diary vols 1-4 published by George Bell & Sons, 1902, embossed Wellington College to cover; Poetical works of R Browning vols 1-2; Essays in criticism by Matthew Arnold, Macmillan 1910; Women artists in all ages and countries, Mrs E. F. Ellet, published by Richard Bentley, 1860 etc

-

1820 item(s)/page

![Reiman (Donald H. [editor]). Shelly and his Circle 1773-1822 [The Carl H. Pforzheimer Library, volumes 7-8], 2 volumes, Cambr](https://cdn.globalauctionplatform.com/bdb07c26-397e-4c2f-bdb4-ae5c00ef4cbe/7f158b8f-5c53-4613-8aa9-ae6000e93bf7/468x382.jpg)