We found 1821 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 1821 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

1821 item(s)/page

FOLLOWER OF GILBERT JACKSONPORTRAIT OF JAMES BOEVEY, AGED 11, FULL-LENGTH IN A GREEN DOUBLET AND HOSE, HOLDING A GLOVE, BY A TABLE WITH AN OPEN BOOK IN A CURTAINED INTERIOROil on canvas (in an 18th century frame)Dated 'AN.O DOM: 1634/AETATIS SUAE II' with identifying inscription (lower right)146 x 99cm (57¼ x 38¾ in.) Provenance: Possibly commissioned by Andreas Boevey (1566-1625), and by descent at Flaxley Abbey, Gloucestershire, until sold Flaxley Abbey, Gloucestershire: Catalogue of the Valuable Contents, Bruton, Knowles & Co., 29 March - 5 April 1960, lot 1295Bought by Mr and Mrs Frederick Baden-Watkins and thence by descent at Flaxley AbbeyLiterature:Compiled by: Arthur W. Crawley-Boevey, 'The Perverse Widow': Being Passages from the Life of Catharina, wife of William Boevey, Esq., London, 1898, p. 37Arthur W. Crawley-Boevey, A Brief Account of the Antiquities, Family Pictures and Other Notable Articles at Flaxley Abbey, co. Gloucester, Bristol, 1912, pp. 11-12, no. 2J. Lees-Milne, 'Flaxley Abbey, Gloucestershire - III: The Home of Mr. and Mrs. F.B. Watkins', Country Life, 12 April 1973, p. 982, fig. 5, The Morning Room This full-length painting is a companion piece to lot 17, Joanna Boevey (1605-64), aged 11, daughter of Andreas Boevey (1566-1625) and his first wife, Esther Fenne. This portrait probably depicts James Boevey (1622-96), Joanna's half-brother, son of Andreas and his second wife, Joanna (née de Wilde). The two portraits were probably painted to mark the children's coming of age when they were eleven. James, merchant and philosopher, was, in later life, only five feet tall, 'slenderly built with extremely black hair curled at the ends, an equally black beard, and the darkest of eyebrows hovering above dark but sprightly hazel eyes' (com accessed 14 June 2022). His early career was as a 'cashier' for the banker Dierik Hoste, and for the Spanish ambassador in London, while in the employ of the Dutch financier Sir William Courten. A known figure in Restoration London, Samuel Pepys described him as: 'a solicitor and a lawyer and a merchant altogether who hath travelled very much; did talk some things well, only he is a Sir Positive; but talk of travel over the Alps very fine' (Pepys, 9.206). Although his writings on 'Active Philosophy' were never published, they circulated widely amongst his friends and acquaintances. In 1642, James Boevey and his half-brother, William, made a joint-purchase of Flaxley Abbey. In 1912, it was argued that the painting was in fact a portrait of Abraham Clarke the Younger rather than James Boevey (A.W. Crawley-Boevey, A Brief Account of the Antiquities, Family Pictures and Other Notable Articles at Flaxley Abbey, co. Gloucester, Bristol, 1912, pp. 11-12, no. 2). This was based on a discrepancy between the date of the painting and the age of the sitter - in 1634, Joanna Clarke's son (née Boevey), Abraham the Younger, born in 1623, was aged 11 while his uncle and Joanna's half-brother, James, born in 1622, would have been 12 years old when the portrait was painted. In the 'old Flaxley List', the painting was recorded as 'Mr. Clarke' and attributed to Van Dyck. However, in retrospect, it seems more likely that Andreas Boevey would have commissioned a portrait of his children, Joanna and James. The Van Dyck attribution seems unlikely if he is to be credited with the companion portrait of Joanna, painted in 1616, as Van Dyck did not arrive in England until 1620 (ibid.). A 19th-century copy of this portrait was painted and published in Crawley-Boevey, A.W.C., The Perverse Widow, Being Passages from the Life of Catharina, Wife of William Boevey, 1898, p. 34. Condition Report: Canvas has been relined and mounted on a later stretcher. The work appears to be in overall good restored condition. A layer of surface dirt and cloudy masking varnish, which prevents proper inspection under UV, but is is presumed there is historic retouching.Condition Report Disclaimer

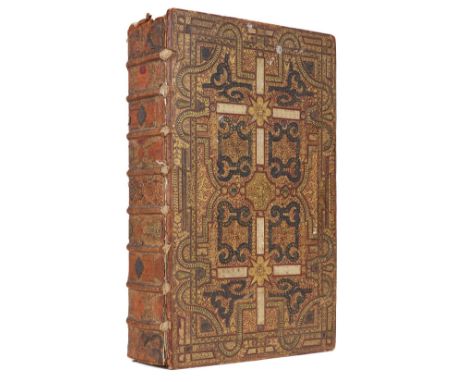

Sedgley (Thomas, binder). The Holy Bible containing the Old Testament and the New, Newly Translated out of the original Tongues and with the Former Translations diligently Compared and Revised. By His Majesties special Command. Appointed to be read in Churches. London: Printed by Charles Bill and the Executrix of Thomas Newcomb deceas'd Printers to the Kings most Excellent Majestie, 1701, engraved general title by Sturt, letterpress New Testament title, Apocrypha present, some woodcut decorative initials, occasional minor spotting and marks, titles and borders ruled in red throughout the volume, Dutch gilt pink endpapers with foliate design, all edges gilt, fine contemporary mosaic binding of scarlet morocco by Thomas Sedgley, extremities rubbed with some wear in places, with joints split and loss to head and foot of spine, some surface losses to spine and covers (particularly to the former), gilt roll decorated raised bands, compartments of spine and both covers densely decorated with a plethora of gilt decorated coloured onlays, forming strapwork designs filled with a profusion of gilt tools and rolls, including leaf sprays, fleurons, seedheads, grotesque face tool, tulip, carnation, and sunflower tools, Tudor roses, etc, edges with seedhead roll, turn-ins with pelmet roll and triple fillets, thick folio (52.5 x 34 cm)QTY: (1)NOTE:Herbert 868.This edition of the Bible is understood to have been supervised by William Lloyd, Bishop of Worcester. The text, printed in large type, fills 1456 pages. Besides the revised marginal dates and chronological Index, the book contains a long note on Jewish Weights and Measures, etc., compiled by Richard Cumberland (1631-1718), Bishop of Peterborough, whose essay on this subject, dedicated to his friend Samuel Pepys (as President of the Royal Society), appeared in 1686. This matter is sometimes appended, with other tables, to subsequent editions of the Bible. In this edition the date of the Nativity is taken as the central event in history, and apparently for the first time in an English Bible the years are reckoned as either 'Before Christ' or 'Anno Domini.' It should be noted that this chronology of the 1701 London folio (since reproduced in most editions of the King James' version) and inserted without any authority in English Bibles for the last two centuries, was based on the Annales Veteris et Novi Testamenti (1650-54), compiled by the James Ussher (1581-1656), Archbishop of Armagh. John Lewis (A complete history of the several translations of the Holy Bible and New Testament into English, 3rd edition, 1818, p. 350) states that this Bible was included among those condemned by the Lower House of Convocation in 1703 for their gross errors (Herbert).Unmistakably the work of Thomas Sedgley (1684-1761), this magnificent mosaic binding - which stylistically bears all the hallmarks of Sedgley's best work - incorporates a number of tools found on other bindings known to be by his hand, such as a wheel of five leaves revolving around its centre and a tulip tool (see number 138 in Maggs, Bookbinding in the British Isles, Catalogue 1075, Part I). It also utilises a highly distinctive grotesque face tool, illustrated in John P. Chalmers's article 'Thomas Sedgley Oxford Binder' in The Book Collector, Autumn 1977, pp.353-370 (number 45). This tiny tool, very like a gargoyle head, is easily overlooked, and its inclusion on this sacred tome is likely to be a kind of private jest on the part of the binder. Chalmers illustrates a mosaic binding by Sedgley similar to ours, on a 1715 Book of Common Prayer, belonging to All Souls College, Oxford. Another such is number 59 in Howard Nixon's Five Centuries of English Bookbinding, covering the dedication copy of John Theobald's Albion, printed in Oxford in 1720 (British Library C.27.f.10). Nixon notes that the Theobald "forms one of a small group of mosaic bindings, sharing the same coloured interlacing strapwork and the same unusual leaf tools, which seem to have been executed in Oxford", mentioning the All Souls prayer book as one of this select group, as well as a three-volume Xenophon, published in Oxford, 1727-35, and a Greek New Testament, printed at Cambridge in 1632, both in the Broxbourne Library.Proceeds from the sale of this lot in aid of All Saints Church, Preston, Gloucestershire and St. Michael & All Angels, Moccas, Herefordshire.

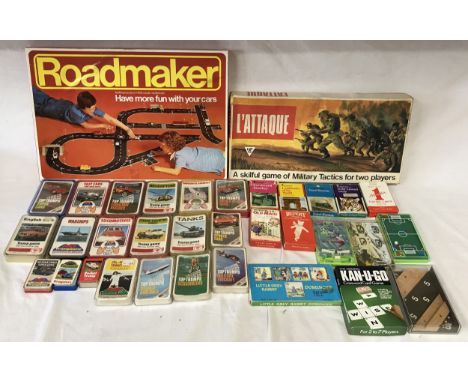

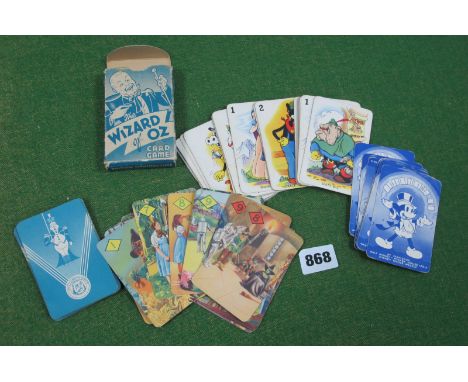

* De La Rue, Thomas, and Co., publisher. The New and Diverting Game of "Golliwogg" consisting of Forty-Eight Pictorial Cards, Depicting the Most Famous Characters and Scenes in the Above Works. Adapted, drawn in fac-simile, and elaborately rendered in Colours from Florence K. Upton's Original Designs, c.1910, forty-eight colour-printed pictorial cards in sixteen sets of three (complete), includes rules booklet (repaired along spine), 90 x 63 mm (3.5 x 2.5 ins), contained in a blue printed slipcase box (not original), together with a duplicate copy with facsimile rules booklet, in a pink slip case, plusGolly Misfitz, a very amusing game, full of hilarious amusement, London: C.W. Faulkner & Co., circa 1906, fifty four chromolithographic pictorial cards in eighteen sets of three, showing doll characters in various traditional and national dress, each card 6.7 x 9.1 cm, original rules booklet (partially detached along spine), presented in original printed box (some closed tears to edges of box), and a small carton containing 28 other packs of cards including: Der Struwwelpeter; Little Grey Rabbit card game, A Pepys game; Highwayman, Chad Valley; Contack, John Waddington; Fairy-Tale Playing Cards, etc., QTY: (1 carton)

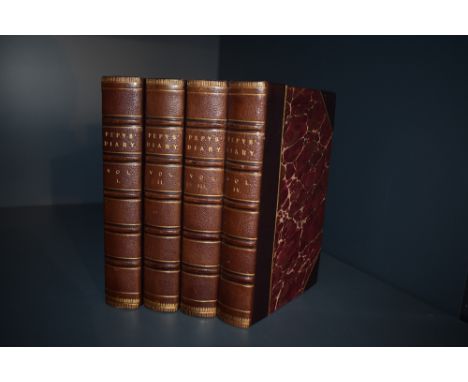

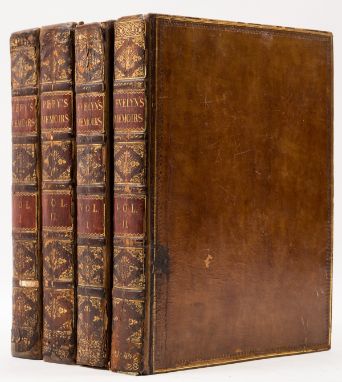

Antiquarian/Binding. Diary and Correspondence of Samuel Pepys...With a Life and Notes by Richard Lord Braybrooke. London: George Bell & Sons, 1894. In four volumes. Bound by Mudie in a half morocco, gilt. A nice set. (4) This edition complete in four volumes as per title pages Bindings square and tight

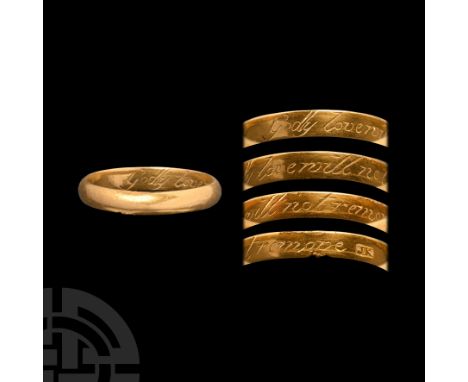

Circa 18th century A.D. The D-section hoop with plain exterior, the interior inscribed 'Godly love will not remove', followed by maker's mark 'JK' in a rectangular cartouche. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, p.43, for this inscription; cf. The British Museum, museum numbers AF.1252 and AF.1253, for this inscription on a ring dated 17th-18th century AD, and museum number AF.1315 for this maker's mark, believed active between 1755-1764, name unknown; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. SUSS-73E152, for a similar ring with this inscription, also stamped 'JK', dated 1700-1800, possibly the same maker's mark.4.17 grams, 21.73 mm overall, 18.94 mm internal diameter (approximate size British R, USA 8 1/2, Europe 18 3/4, Japan 18) (3/4 in.). Ex Albert Ward collection, 1974-1985. East Anglian private collection. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

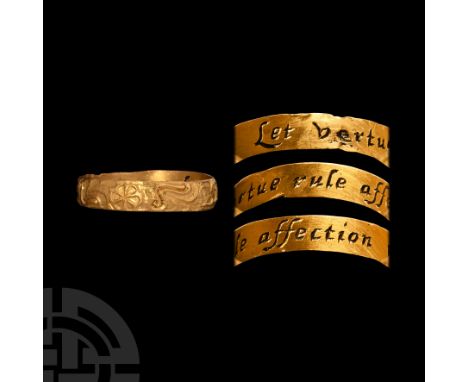

17th-18th century A.D. Composed of a chased exterior displaying flower heads and animals, the interior inscribed 'Let vertue rule affection' and filled with black enamel, followed by unidentified maker's stamp 'P' within a shield-shaped cartouche. Cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, record id. HAMP-CD6223, for another ring with this inscription and with an exterior design executed in similar style.1.36 grams, 17.09 mm overall, 15.59 mm internal diameter (approximate size British J, USA 4 3/4, Europe 8.69, Japan 8) (5/8 in.). Acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

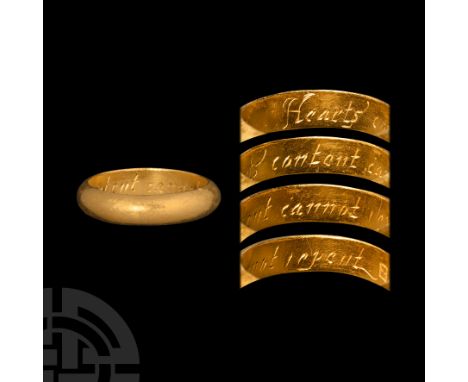

17th century A.D. Composed of a carinated outer face and inscription to interior in cursive script: 'Hearts content cannot repent' followed by a maker's stamp formed as florid a letter 'I' within a rectangular cartouche. Cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1266, for a ring with this inscription dated 17th century; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, record ids. WILT-AFE9A5, and GLO-D67CD3, for similar rings with very similar inscriptions dated 17th century; cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, 1931, p.46, for two very similar inscriptions.6.54 grams, 21.46 mm overall, 17.32 mm internal diameter (approximate size British N, USA 6 1/2, Europe 13.72, Japan 13) (7/8 in.). Acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

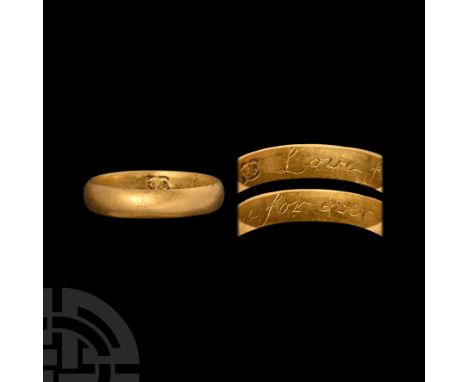

1650-1725 A.D. Composed of a gently carinated hoop, the interior inscribed in cursive script 'Love is the bond of pease'. Cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1339, for this inscription with slight spelling variation and for a similar plain exterior; cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, 1931, p.73, for this inscription with slight spelling variation; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, record id. SUSS-04EA22, for a similar style of ring also heavy at 7.43 grams.7.81 grams, 22.97 mm overall, 18.75 mm internal diameter (approximate size British R, USA 8 1/2, Europe 18 3/4, Japan 18) (7/8 in.). Found whilst searching with a metal detector on 28th March 2022 Mr Graham Higgins, near Hatford, Oxfordshire, UK.Accompanied by a copy of the report for HM Coroner by the Finds Liason Officer (FLO) for the British Museum's Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) for Oxfordshire under Treasure reference number OXON-FC03F7. Accompanied by a copy of the letter from HM Senior Coroner for Oxfordshire disclaiming the Crown's interest in the find. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

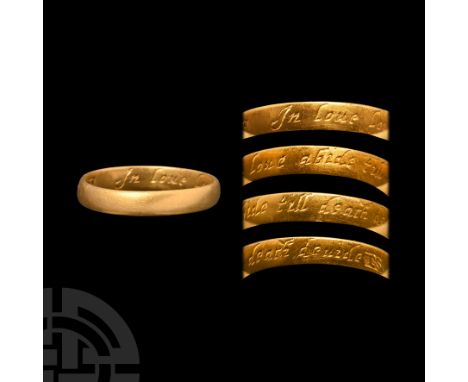

18th century A.D. Inscribed to the hoop interior together with maker's stamp 'RD' within shaped cartouche. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, 1931, p.72, for this posy.6.16 grams, 22.60 mm overall, 19.48 mm internal diameter (approximate size British T, USA 9 1/2, Europe 21.26, Japan 20) (3/4 in.). From the collection of a North American gentleman, formed in the 1990s. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

17th-18th century A.D. Displaying a circumferential band of six-armed stars to the exterior with some remains of enamelling to the fields; the interior inscribed 'THY + FAITH + FAVLS + NOT' (possibly: thy faith fails/false not). Cf. The British Museum's Portable Antiquities Scheme, record id. SWYOR-FA9028, for a ring with the same exterior design, dated 16th-17th century A.D. and record id. WMID-C2D522, for an example of the use of 'favls' to mean 'false'.1.20 grams, 16.93 mm overall, 14.95 mm internal diameter (approximate size British I, USA 4 1/4, Europe 7.44, Japan 7) (5/8 in.). Acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

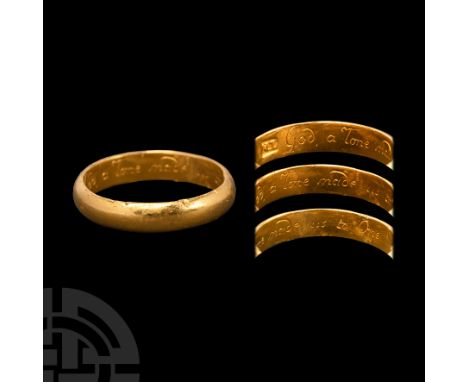

18th century A.D. Inscribed 'God a lone made us to One WME' around the interior, the initials being M for family name with W for male forename and E for female forename, with maker's mark stamped 'NL' in rectangular cartouche, possibly for the northern goldsmith Nicholas Lee. 5.59 grams, 22.23 mm overall, 19.15 mm internal diameter (approximate size British R, USA 8 1/2, Europe 18 3/4, Japan 18) (7/8 in.). From the collection of a North American gentleman, formed in the 1990s. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

17th-18th century A.D. Composed of a slender hoop inscribed around the interior, maker's stamp 'TS' in rectangular cartouche, possibly for goldsmith Thomas Sharp. Cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1534, for this maker's stamp or very similar and AF.1311, for a similar posy; cf. The British Museum's Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, record id. KENT-F5292E, for a very similar posy.3.03 grams, 19.90 mm overall, 17.05 mm internal diameter (approximate size British O, USA 7, Europe 14.98, Japan 14) (3/4 in.). From the collection of a North American gentleman, formed in the 1990s. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.] For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price

16th-17th century A.D. Composed of a decoratively notched hoop divided into chased rhomboidal panels displaying foliate tendrils and horizontal hatching alternately; the interior inscribed in Roman capitals with the Latin phrase: 'x x x x VIVE x VT x VIVAS'. Cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, record ids. KENT-1F5049 and DUR-23C436, for other rings with this inscription; cf. The V&A Museum, accession number M.75-1960, for a similar design exterior dated 16th century A.D.2.08 grams, 19.25 mm overall, 17.40 mm internal diameter (approximate size British M 1/2, USA 6 1/4, Europe 13.09, Japan 12) (3/4 in.). Acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK. The literal translation here is live that you may live, but is meant to convey the sentiment: live life to the fullest. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

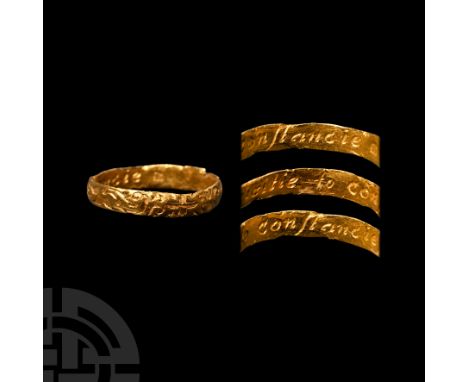

Late 17th-18th century A.D. Composed of a slender convex hoop engraved with crowned conjoined hearts flanked by birds, in turn pursued by bounding hounds, scrolling foliage and a cross at base; trace remains of enamelling; interior inscribed in cursive script: 'No felicitie to constancie', together with maker's stamp 'IY' in a square cartouche. Cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme, record ids. HESH-23BC20 and SUR-6A3232, for broadly comparable design elements.1.38 grams, 17.35 mm overall, 15.48 mm internal diameter (approximate size British J, USA 4 3/4, Europe 8.69, Japan 8) (3/4 in.). Acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK. IY goldsmith's mark possibly for James Young of London, see Jackson, Sir C.J., English Goldsmiths and Their Marks, London, 1921, p.215. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [No Reserve] [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website.]

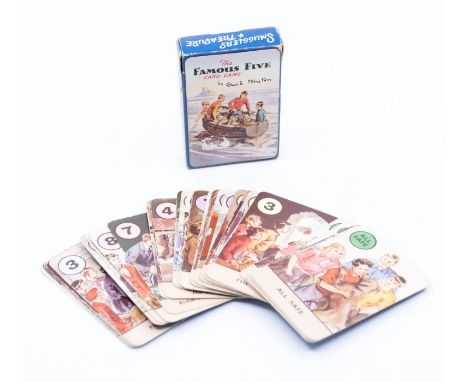

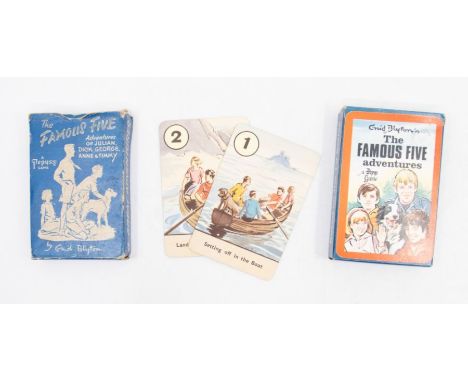

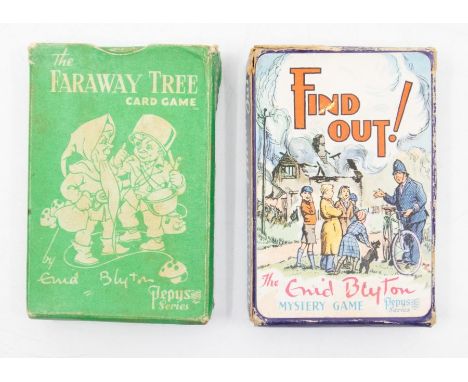

Blyton, Enid. The Secret Seven Card Game: 44 cards with instruction booklet in original box. Box has lost one inner flap, some handling to the cards but no creasing, tog. w/ The Famous Five Card Game in original box with instructions booklet and letter (printed) from Enid Blyton, bearing price label of 3/11d. Both produced by Pepys Games, Castell Bros Ltd. (2)

Blyton, Enid. The Famous Five Card Game, boxed, with 12pp instruction booklet. Box has some wear, hinge loss and white lettering coloured in graphite pencil, tog. w/ another set promoting the TV series, 1978, also boxed. Produced by Castell Bros (Pepys Games), Castell Larby Ltd, and Darrell Waters Ltd, 1958-1978 (2)

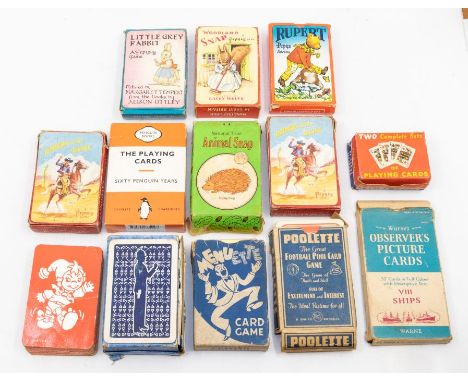

Pepys Card games, 1950s or later, inc. Riders of the Range, 2 sets boxed; Rupert; Little Grey Rabbit; Woodland Snap, cards by Racey Helps, all Pepys (Castell Bros) games, tog. w/ Poolette, The Great Football card game, box damaged with loss, and others, 12 sets plus some loose Noddy cards (12)

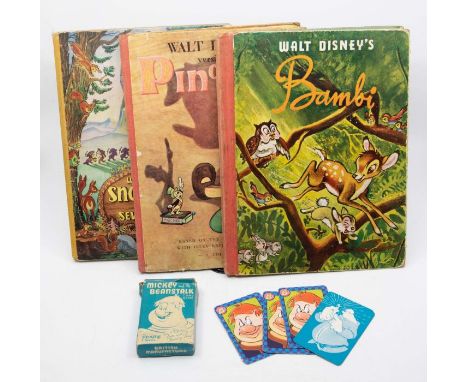

Disney, Walt. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs; Pinocchio; Bambi, all with colour illustrations, Bambi has 4 plates before title, some wear to boards and shaken, tog. w/ a boxed card game, Mickey and the Beanstalk, full set, 44 cards, folding beanstalk card and instructions, made by Pepys UK, some cards creased, box worn (4)

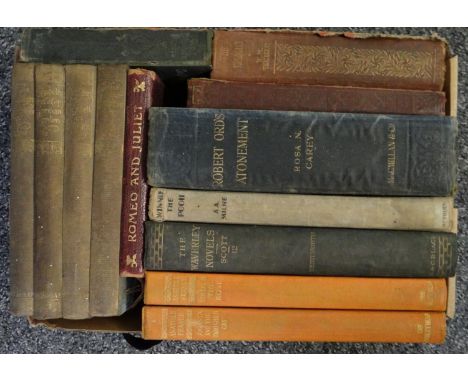

Box of hardback vintage books to include: 'Romeo & Juliet', 'The Waverley Novels', two of the works of Anatole France 'Jacasta and the famished cat' and 'Under the Rose' 'Winnie the Pooh' by A.A Milne 1934, 'The Virginians' Thackeray, 'Pepys Diary', set of Macmillan & Co books; 'The Benefactress', 'Elizabeth and her German garden' etc, 'Pilgrim's Progress', 'Robert Ord's Atonement' Rosa N Carey etc. (B.P. 21% + VAT)

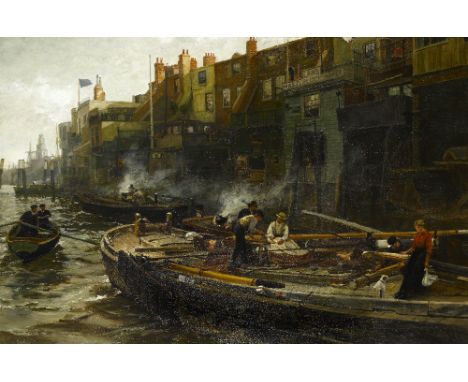

Charles Napier Hemy, RA RWS (British, 1841-1917)The Riverside, Limehouse signed and dated 'C.N.H. 1914' (lower right)oil on canvas122.5 x 182.9cm (48 1/4 x 72in).Footnotes:ProvenanceWith the Fine Art Society.Anon. sale, Christie's, 17th May 1923, lot 155 for £157.10.0 (F.A.S vendor), acquired by Gooden and Fox.William Hesketh Lever, 1st Viscount Leverhulme (1851-1925), Lancashire.The Bungalow and Rivington Hall, Horwich, Lancashire sale, Knight, Frank & Rutley, London, 9-17 November 1925, lot 1105, p.68.Bolton Museum and Art Gallery (acquired from the above sale).Sale, Bonhams, 25th January 2012, lot 165, where acquired by the current owner. ExhibitedLondon, Royal Academy, Summer Exhibition, 1914, no. 369.London, Royal Academy, Winter Exhibition, 1922. LiteratureRoyal Academy Pictures and Sculpture 1914, illustrated p 82.The name Limehouse comes from the lime kilns established there in the 14th Century and was used to produce quick lime for building mortar. In 1660, Samuel Pepys visited a porcelain factory in Duke's Shore, Narrow Street, whilst the Limehouse Pottery, on the site of today's Limekiln Wharf, was established in the 1740s as England's first soft paste porcelain factory.Limehouse became a significant port in late medieval times, with extensive docks and industries such as shipbuilding (which was established in the 16th century and thrived well into the 19th century), ship chandlering and rope making. By the Elizabethan era many sailors had homes there and by early in the reign of James I about half of the population of 2000 were mariners. Limehouse Basin opened in 1820 as the Regent's Canal Dock. This was an important connection between the Thames and the canal system, where cargoes could be transferred from larger ships to the shallow-draught canal boats. As the age of steam led to bigger ships, the facilities at Limehouse became inadequate. However, local ingenuity found a highly successful alternative: many of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution's lifeboats were built in Limehouse between 1852 and 1890. Though no longer a working dock, Limehouse Basin with its marina remains a working facility. The wharf buildings that have survived, are now highly desirable residential properties. Taylor Walker began brewing at the site of today's 'Barley Mow' pub in 1830. This stretch of the Thames was known as Brewery Wharf, whilst from a little further along the embankment, the first voluntary passengers left for Australia.From the Tudor era until the 20th century, ships crews were employed on a casual basis and would be paid off at the end of their voyages. Inevitably, permanent communities of foreign sailors became established, including colonies of Lascars and Africans from the Guinea Coast. From about 1890 onwards, large Chinese communities at both Limehouse and Shadwell developed, established by the crews of merchantmen in the opium and tea trades, particularly Han Chinese, creating London's first and original Chinatown. The resulting opium and gambling dens soon attracted a wider clientele than visiting Chinese sailors, luridly described by, amongst others, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Oscar Wilde. Like much of the East End it remained a focus for immigration, but after the devastation of the Second World War many of the Chinese community relocated to Soho.The Hemy family set sail for Australia when he was 10 years old and, as he later recalled, 'I can remember it (the open sea) entered my soul, it was imprinted on my mind, and I never forgot it'. Hemy sketched and painted at locations on Narrow Street's river front and other notable artists who used Limehouse as a backdrop for their paintings included James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) and James Jacques Joseph Tissot (1863-1902). Whistler was living near the docks in Wapping between 1859-1863 and produced a series of etchings known as 'The Thames Set', which must have been a great influence on Hemy. These concentrated on the picturesque wooden buildings of the lower Thames, the barges, wharfs, warehouses and inns of Wapping, Rotherhithe and Limehouse, together with the barge men and labourers who worked there. Whistler also produced a major oil painting titled Wapping, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1864, no. 585, (collection National Gallery of Art, Washington). In 1869, Hemy was living in Fulham, not far from Whistler's studio in Chelsea. He may have been introduced to Whistler by his friend Tissot, whose work in the 1870s had a more direct influence on Hemy. Tissot painted scenes of beautiful ladies and sea captains on board ships and in interiors with the Thames and the black masts of ships seen through the windows in the background, e.g. An Interesting Story of c. 1872 (collection National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne). An interested spectator of Hemy at work was a young Frank Brangwyn. As a boy in the 1870s, Brangwyn often wandered down among the old buildings of the Thames where he would watch 'a magnificent looking man in a velvet coat painting a big picture. I would sneak up and admire him.'The Thames estuary continued to draw Hemy and he painted a series of pictures of the busy mouth of the Thames i.e. The Shore at Limehouse (exh. R.A. 1871, no. 435), Blackwall (exh. R.A. 1872, no. 198), London River - the Limehouse barge-builders (exh. R.A. 1875, no. 108), The harbour master's home, Limehouse (exh. R.A. 1901, no. 1039), 1901, Home at last, 1909, Limehouse Hole, (exh. R.A. 1910, no. 862) and The barge, Limehouse, (exh. R.A. 1918, no. 356). London River, his 1904 R. A. exhibit (no. 236), an evocation of Hemy's favourite stretch of the Thames with Hawksmoor's famous St. Anne's church prominent on the skyline, was bought by the Chantrey Bequest for £1,000 and now hangs in Tate Britain.The old buildings on the banks of the river at Limehouse and Wapping provided excellent subjects and Hemy used the boatmen as models; his knowledge of the sea enabling him to establish an easy rapport with them. Of his RA exhibit Limehouse barge builders of 1875 (collection South Shields Museum and Art Gallery), Hemy wrote, 'I painted the picture altogether from nature sitting in a barge and talking with the workmen.'Hemy's memorial exhibition took place at the Fine Art Society in 1918 where 101 of his works were shown.For further information on this lot please visit Bonhams.com

Pepys (Samuel) Memoirs of ... comprising His Diary from 1659 to 1669 ... and a selection from his Private Correspondence, 2 vol., 1825 § Evelyn (John) Memoirs Illustrative of the Life and Writings of..., edited by William Bray, 2 vol., upper joint cracked to vol.1, 1818, first editions, half-titles, engraved portrait frontispieces and plates, some offsetting or light foxing, uniform in contemporary calf, spine gilt with red morocco spine labels, rebacked preserving original spine strip, a little rubbed along repairs, 4to (4)

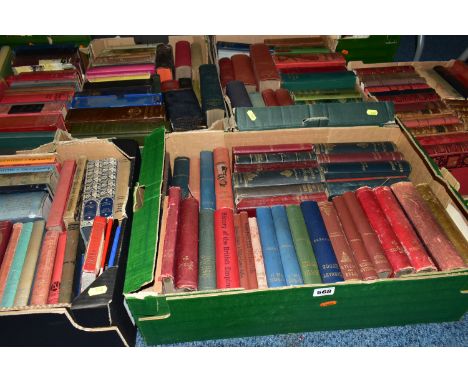

SIX BOXES OF BOOKS containing approximately 195 old or antiquarian titles in hardback format, subjects include encyclopaedic and lexical works, bibles and religious titles, diaries, historical and military works, poetical compilations and classic novels, authors include William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, David Lloyd George, Sir Walter Scott, Samuel Pepys, Mark Twain, Stephen Potter and many others, the lot includes eleven Dickens Works, 'The Charles Dickens Edition' published by Chapman & Hall Ltd, London, printed by William Clowes & Sons

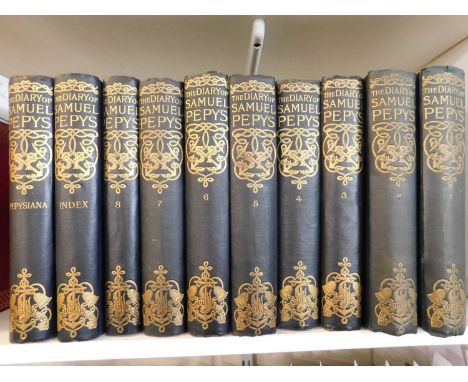

NO RESERVE History and Politics.- Gibbon (Edward) The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, 12 vol., new edition, portrait frontispiece to vol. one, folding maps, ink ownership inscription "F. Trinch" to each title, a few short tears to maps without loss, some browning and staining, contemporary mottled calf, rubbed at extremities, 1788-1790 § Pepys (Samuel) The Diary of Samuel Pepys, 8 vol. only (of 10, lacking vol. 2 and 8), edited by Henry B. Wheatley, frontispiece to each volume, plates, some spotting, edges foxed, original cloth, spines gilt, lightly stained, t.e.g., 1893-1899 § Bacon (Francis) The Life and Letters of Francis Bacon, 7 vol., edited by James Spedding, pages toned, some light scattered spotting, some vol. with bookplates, original cloth, rubbed at extremities, 1861-74; and c. 70 others relating to history, philosophy and politics, including works by or relating to Winston Churchill, Benjamin Disraeli and David Lloyd-George, v.s. (c. 100)

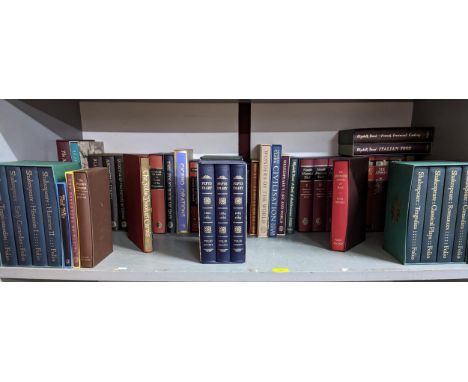

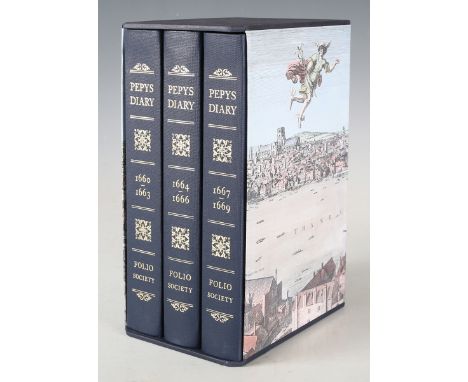

FOLIO SOCIETY (publisher). - Samuel PEPYS. Pepys's Diary. London: The Folio Society, 1996. 3 vols., 8vo (243 x 130mm.) (Mild toning.) Original cloth covers, slipcase (minor surface loss). Provenance: M.J. Hall (name-plate verso half-title). - And a further thirty volumes published by The Folio Society (including Truman Capote's 'In Cold Blood', 2011, 8vo) (33).Buyer’s Premium 24.5% (including VAT @ 0%) of the hammer price. Lots purchased online via the-saleroom.com will attract an additional premium of 5% (including VAT @ 0%) of the hammer price.

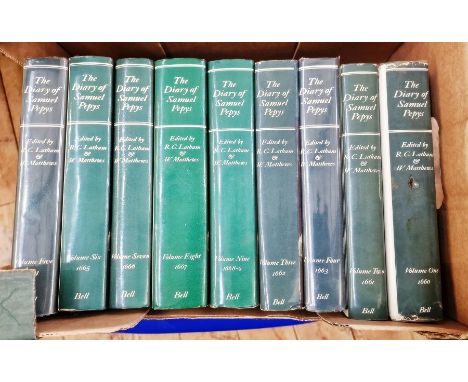

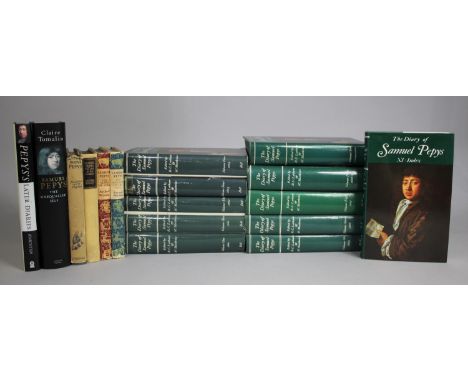

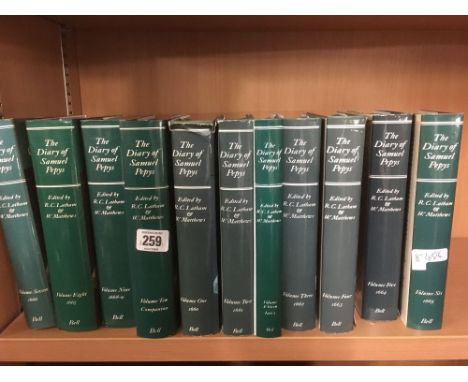

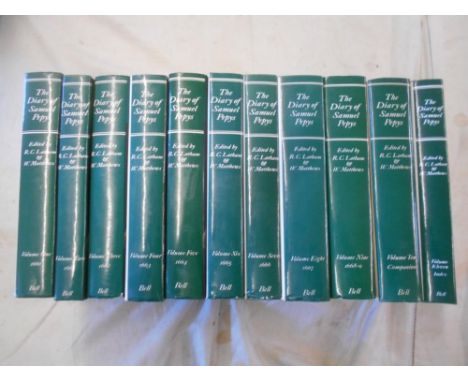

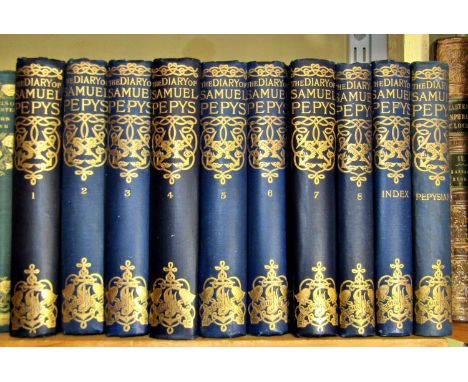

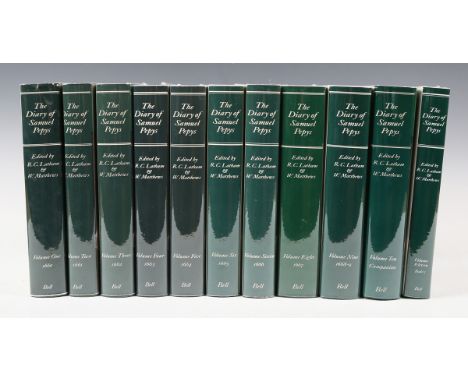

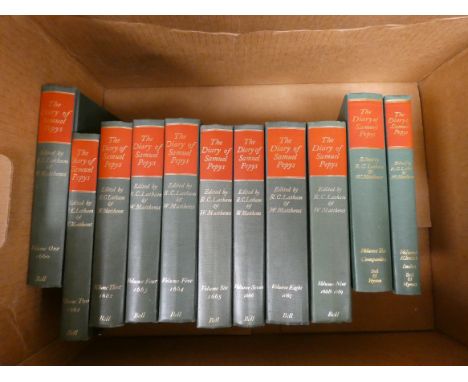

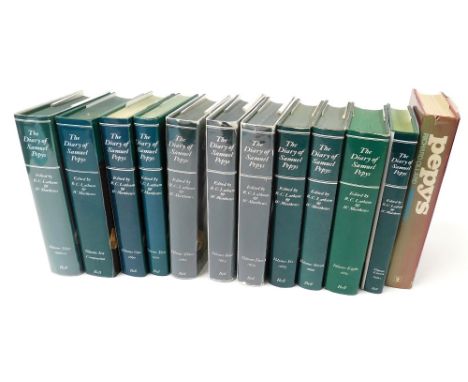

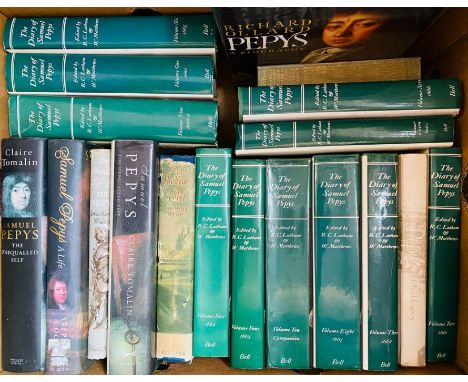

LATHAM, Robert and William MATTHEWS (editors). The Diary of Samuel Pepys. London: G. Bell and Sons Ltd., 1971-1983. 11 vols., mixed editions, 8vo (215 x 135mm.) (Mild toning.) Original green cloth, dust-jackets. Note: volumes 4-11 are first editions (11).Buyer’s Premium 24.5% (including VAT @ 0%) of the hammer price. Lots purchased online via the-saleroom.com will attract an additional premium of 5% (including VAT @ 0%) of the hammer price.

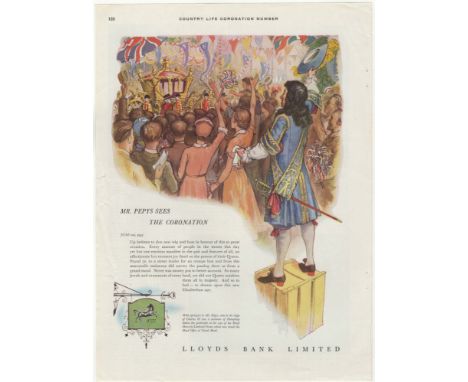

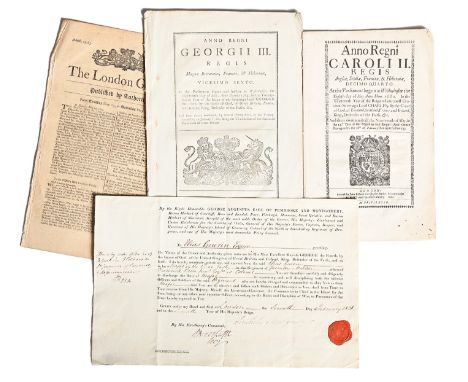

The Royal Navy under Charles II. An Act for providing Carriage by Land, and by Water, for the use of His Majesties Navy and Ordnance, London: Printed by John Bill and Christopher Barker, 1662, Black Letter printing, [12pp], worm trails to lower-right margin, disbound, small folio, further unconnected ephemera, including a George III parliamentary act, An Act for laying a Toll upon all Horses and Carriage passing on a Sunday over Blackfriars Bridge [...], London: Eyre and the Executors of W. Strahan, 1786, disbound, small folio, The London Gazette, Numb. 15483, Tuesday May 25, to Saturday May 29, 1802, 8pp, folio, The Channel Islands, a George IV militia officer's commission, Major Elias Guerin Esquire, 1st or East Guernsey Militia, signed and bearing the armorial red wax seal of the then governor of Guernsey, George Herbert, 11th Earl of Pembroke, the foolscap printed by Easton, Endless-street, Sarum, and inscribed in ink manuscript, (4). The 'Act for Land Carriage' appears in the diary of Samuel Pepys, then Secretary to the Admiralty, on Saturday, 13th May, 1665, when he visits 'the Atturney (sic) General, about advice [...] which he desired not to give me before I had received the the King's and Council's order'; on his return home he 'bespoke the [late] King's works [the Eikon Basilike], will cost 50s.'

A selection of The Temple Shakespeare, published by J. M. Dent, titles including: The Tempest; Hamlet; As You Like It; Macbeth; King Henry VIII; Twelfth Night; together with a selection of antiquarian hardback books, titles including: Leaves from the Diary of Samuel Pepys, edited by J. Potter Briscoe, 1901; The Book of Household Management, by Mrs Isabella Beeton, 1893; The Watchers of the Trails, by Charles G. D. Roberts, 1904; A School Atlas of English History, by Samuel Rawson Gardiner, 1910; The Jungle Book, by Rudyard Kipling, 1918; and others.

Royal Mint Limited Edition Silver Proof Coins, includes 2019 The Gruffalo 50p, 2019 350th anniversary of Samuel Pepys Last Diary Entry £2 coin and the Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-glass One Ounce Silver Proof Coloured coins all in Original Cases with Certificate of Authenticity.

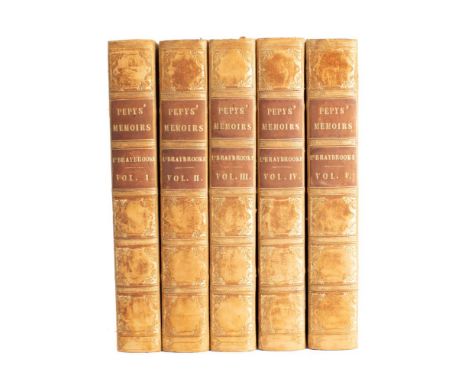

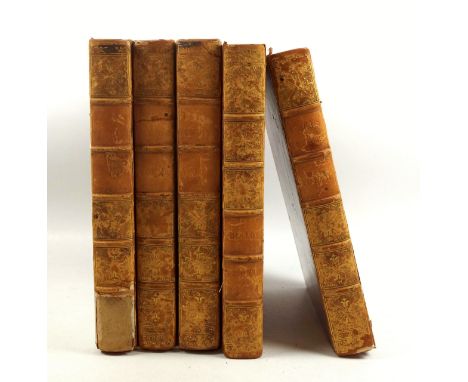

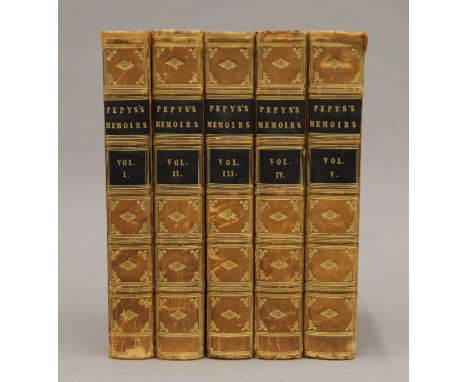

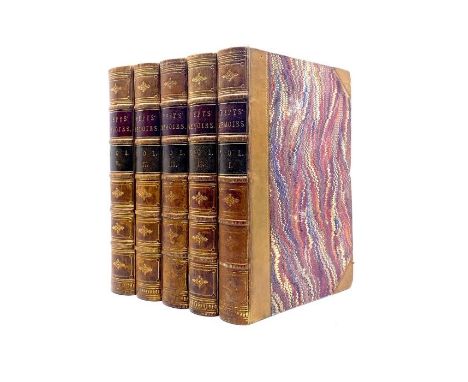

Pepys, Samuel. Memoirs, Diary & Private Correspondence, edited by Richard Lord Braybrooke, in five volumes, London: Henry Colburn, 1828. Octavo, handsome C19 half-calf with morocco title labels lettered in gilt, marbled boards/endpapers/edges, engraved portrait frontispiece to each volume, plus three further plates in Vol. I (two folding), one in Vol. II, one in Vol. III (folding), and one in Vol. V (folding). Contents very good, clean, bright, occasional pale spotting in places, decorative bindings tight & square, slight bumping & wear to corners/extremities, an attractive set (5)

-

1821 item(s)/page