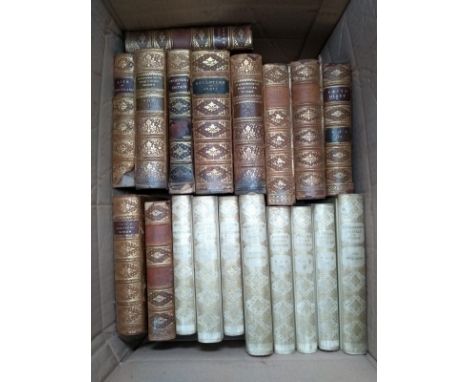

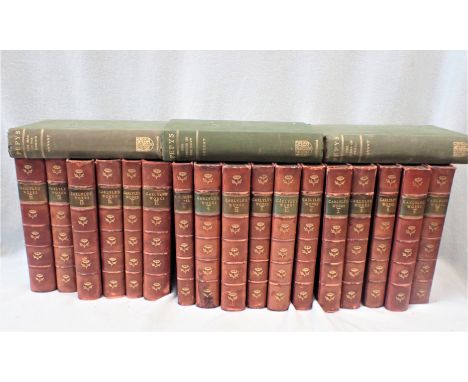

A mixed box of good hardback books many in full leather bindings to include Pepys' diary vols 1-4 published by George Bell & Sons, 1902, embossed Wellington College to cover; Poetical works of R Browning vols 1-2; Essays in criticism by Matthew Arnold, Macmillan 1910; Women artists in all ages and countries, Mrs E. F. Ellet, published by Richard Bentley, 1860 etc

We found 1821 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 1821 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

1821 item(s)/page

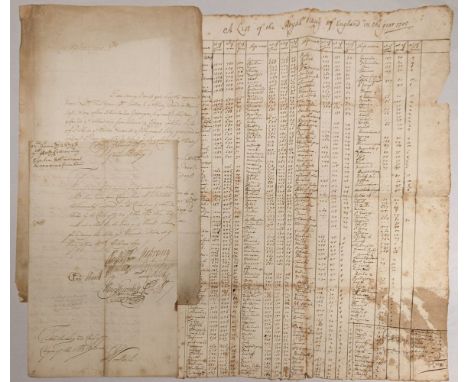

* Royal Navy. Manuscript list of Royal Navy ships, 1705, single sheet, written to one side in a neat hand in four tabled columns, listing the names of all the 279 ships in the Royal Navy in 1705, listed under the rating (one to six) and with the weight of each ship, number of crew and guns, listings total each class along with other types of ships (i.e. fire ships, hulks, hospital ships etc.), docketed in French to verso 'a leste des fregattes d'Anletterre et des ... pour l'anne 1705', folded, some early waterstains, folio (34 x 43 cm), together with: Charles II Royal Navy finances, Single sheet document signed John Shales, from the recently appointed Inspector of Excise Revenue to Charles II's First Minister, the Earl of Danby, on the issue of delayed returns into the financial state of the Navy, [London] 2nd December 1674, single sheet written in secretary hand signed by Shales, giving reference to Samuel Pepys "the charge of the Navy continues its progression to a degree far beyond the establishment which your Loxx. (Lordships) has design'd to consult Mr Pepys in & put a stopp to", addressed & docketed, folded for delivery with evidence of seal wax, folio, Royal Navy Board, A collection of five manuscript documents signed by Sir Cloudsley Shovell & others, issued to the store keeper at their Majesties Yard at Woolwich regarding supplies etc., 1693-1700, written in secretary hand, few torn, small folio, William III Army, A manuscript listing the cost of running the Army during the reign of William III, [London] November 7th 1700, 3 pages of neatly written tables comprising 92 entries listing regiments such as the Horse Guards, Light Horse, Dragoons, Langstone's Regiment of Foot, and other regiments and personal companies such as the Hanovers, and the French Reformed Officers of the Rhine etc., integral 4th page docketed, some toning, folded, folio, plus other documents, including a report on testing an instrument to assist artillery, c.1825, etc.Qty: (13)

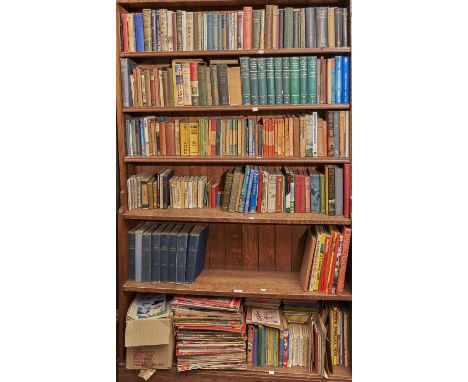

A box of assorted volumes to include The Diary of Samuel Pepys, Girls Own Paper No. 5, Girls Own Annual, etcCondition report: To also include:Burke + Norfolk.Ladies Magazine 1824.Punch 1916, 1953 and 1852.Olympics 1936.Our Battalion 1902.Older books are in very well-read condition with considerable wear, but mostly appear intact.

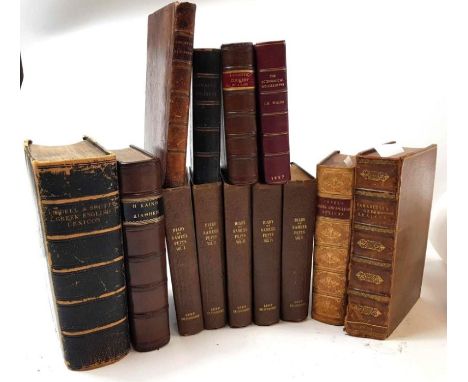

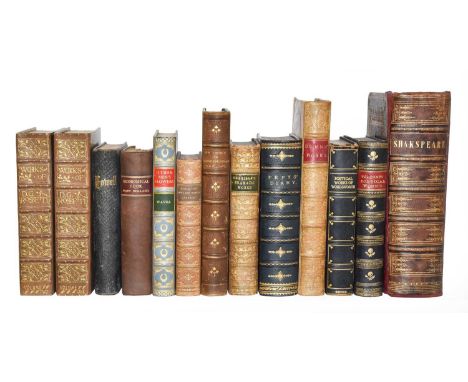

Bindings. Other Men’s Flowers. An Anthology of Poetry Compiled by A. P. Wavell, London: Jonathan Cape, 1968, contemporary light blue calf by Bayntun; Memoirs of Samuel Pepys, London: Frederick Warne and Co., c.1880, contemporary blue half morocco by Mudie; The Collected Works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, London: Ellis and Elvey, 1890, 2 volumes, contemporary olive-brown crushed morocco gilt for John Bumpus; The Complete Works of Robert Burns, Edinburgh: William P. Nimmo, c.1880, contemporary tan half calf, and 21 others similar, mainly 19th-century editions of English literature in fine leather bindings, all 8vo (qty: 26)

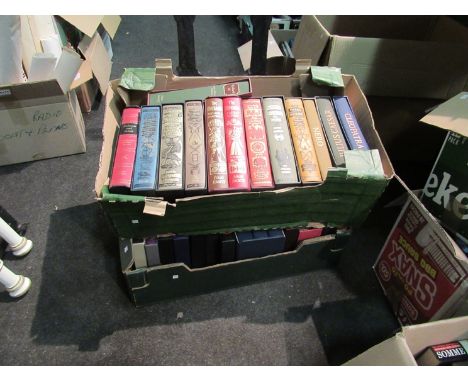

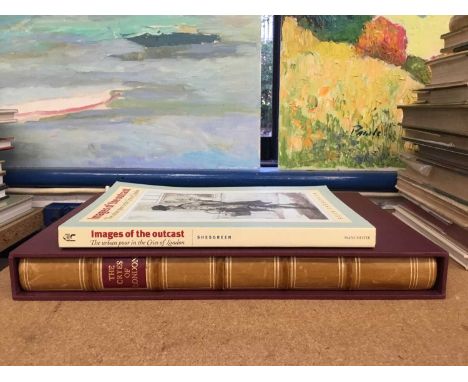

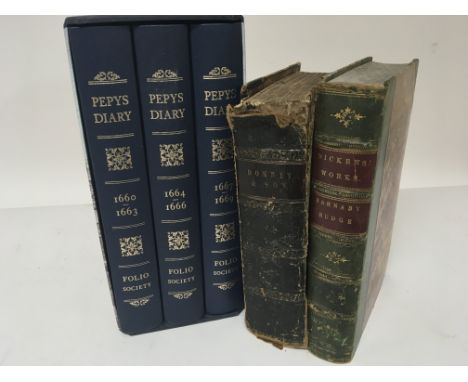

[Folio Society] Shakespeare's Romeo & Juliet; Hamlet; King Richard II; Antony & Cleopatra and Julius Caesar (5 volumes), Pepys Diary 1660-1669 in 3 volumes, London Characters & Crooks by Henry Mayhew, The Fatal Shore by Robert Hughes, The Plums of P.G. Wodehouse, The Pick of Punch and 3 others, all but one in original slipcases

BOOKS, two boxes containing twenty-one Antiquarian titles including works by Felicia Hemans, Samuel Pepys, William Shakespeare, Max Adeler, H.V. Morton, Edward Fitzgerald and Florence L. Barclay and thirty-two children's titles dating from the Victorian era until the 1950s and five Rupert annuals

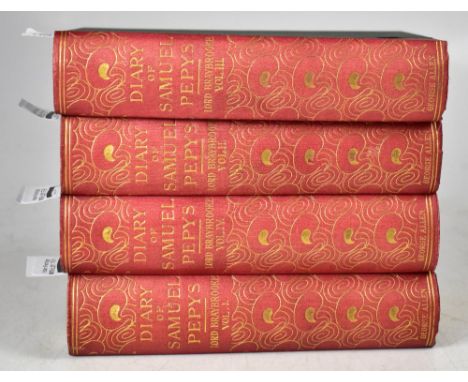

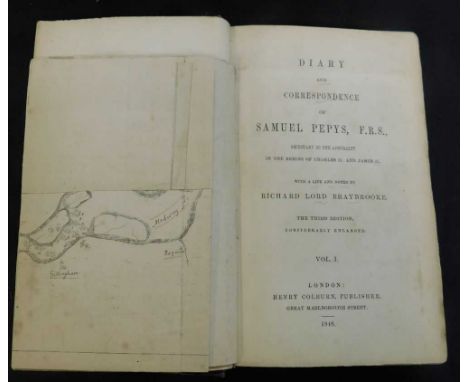

PEPYS, SAMUEL, LORD RICHARD BRAYBROOKE; 'Diary and Correspondence of Samuel Pepys, F.R.S.', London: George Allen & Company, Ltd., 1911. 'A verbatum reprint of the edition of 1848-49', though seemingly the first edition from this publisher, with reprints following in 1914 and several times in the 1920s, complete in four volumes.

A PAINTED PLASTER RELIEF FRAGMENT PANEL OF A CHARIOTAttributed to Samuel Pepys Cockerell, after the north frieze of the Parthenon, Temple of Zeus, Olympia, first half 19th century119cm wide, 12cm deep, 93cm high (46 1/2in wide, 4 1/2in deep, 36 1/2in high) Footnotes:Provenance: Porteus Terrace, Paddington.Christie's, London, South Kensington, 26 October 2016, The Hone Collection, lot 118.This lot is subject to the following lot symbols: * TP* VAT on imported items at a preferential rate of 5% on Hammer Price and the prevailing rate on Buyer's Premium.TP Lot will be moved to an offsite storage location (Cadogan Tate, Auction House Services, 241 Acton Lane, London NW10 7NP, UK) and will only be available for collection from this location at the date stated in the catalogue. Please note transfer and storage charges will apply to any lots not collected after 14 calendar days from the auction date.For further information on this lot please visit Bonhams.com

SAMUEL PEPYS: DIARY AND CORRESPONDENCE, ed Richard Lord Braybrooke, London, Henry Colburn, 1848-49, 3rd edition, 5 vols, considerably enlarged, vol 1 engraved port of Pepys, trimmed and remounted on leaf preceding preface, facsimile plate as list, extra illustrated with an engraved port of Elizabeth Pepys and folding plan (splits at fold) as frontispieces, quantity of pencil annotations, original blind stamped cloth gilt worn, vol 5 with rubber stamp of Brighton Atheneum, vol 1 old booksellers label on front paste down, contains pencil notes in each volume by Peter Cunningham (1816-1869) (5)

[AP] A TROOPER~S SWORD OF THE EARL OF OXFORD~S REGIMENT OF HORSE, LATER THE ROYAL HORSEGUARDS (THE BLUES), LAST QUARTER OF THE 17TH CENTURY with single-edged blade double-edged towards the point and formed with a pair of narrow fullers along the back-edge (extensive rust), brass hilt comprising double shell-guard cast in relief on each side with the crest of Aubrey de Vere, 20th Earl of Oxford enclosed by the most Noble Order of the Garter beneath a coronet, and linked to the knuckle-guard by a scrolling bar front and back, short quillon, globular pommel decorated front and back en suite with the shell-guard, and original wooden grip (cracked) with a moulded collar at the top 73.5 cm; 29 in blade Aubrey de Vere, 20th Earl of Oxford (1627-1703) claimed to have led a ~regiment of scholars~ from Oxford for the king in the first Civil War, though there is limited evidence of this. Shortly after his marriage to Anne Bayning in 1647 he embarked upon his career as a royalist conspirator, being considered for the post of general of the royalist forces in 1665. He was one of the so-called ~new lords~ who took his seat in the house on 27 April 1660 and was made a knight of the garter the following month. The king also appointed him lord lieutenant of Essex and gave him command of the King~s regiment of horse, or, as it was commonly known while he was its colonel, the Oxford Blues. The regiment enjoyed the King~s favour and was entrusted with special duties attaching it to the sovereign. He is recorded living riotously on the Piazza at Covent Garden in the 1660s, where on one occasion a brawl erupted among his guests which was only quelled after the arrival of troops dispatched by the duke of Albemarle. Samuel Pepys recorded in 1665 that he visited Oxford~s house on business, and wrote ~his lordship was in bed at past ten o~clock: and Lord help us, so rude a dirty family I never saw in my life~. Another sword from this group is preserved in the Museum of London (inv. no. A12992) and another is illustrated Brooker 2016, pp. 57. Property from the David Jeffcoat Collection (1945-2020) Part proceeds to benefit Westminster Abbey

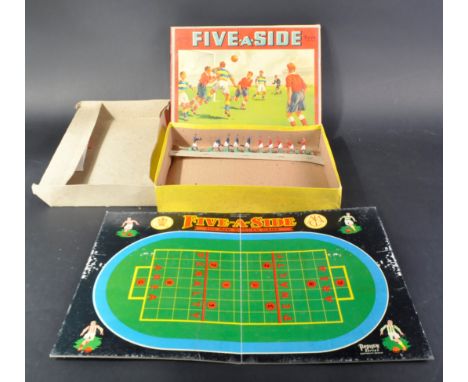

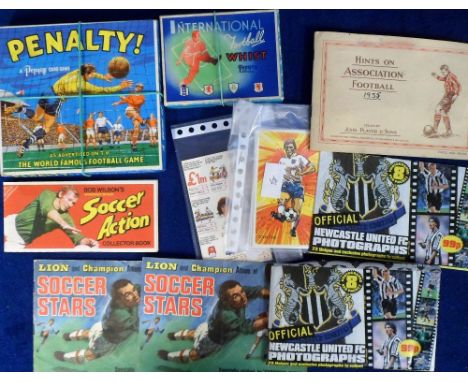

Football, a selection of items inc. Pepys, Box Games, Penalty & International Football Whist, Shredded Wheat, Bob Wilson's Soccer Action Collector Book, Player's, Hints on Association Football (set, 50 cards) in special album, a packet of Newcastle FC Official Photographs, plus a few other items (gen gd)

Collection of books, to include: J. M. Barrie, 'Peter Pan', illustrated by Arthur Rackham (London: Hodder and Stoughton, c. 1910), 'Diary of Samuel Pepys' (5 volumes, London: Henry Colburn), Otto Jah, 'The Life of Mozart' (3 volumes, London: Novello, Ewer and Co. 1891), Humboldt's Cosmos (2 volumes, London: Longman, 1849), John Bowlder, 'Select Pieces' (2 volumes, London, 1817), Francis Bacon, 'Of the Proficience and Advancement of Learning' (London: William Pickering, 1838), Samuel Croxall, 'Fables of Aesop' (London: Longman, 1831), Smollett's 'History of England' (Volumes 3, 4, 5, 6, London, 1794), William Wilberforce, On Christianity (London: Cadell and Davies, 1811). All leather-bound, some with gilt lettering and raised bands to spines. (1 box)

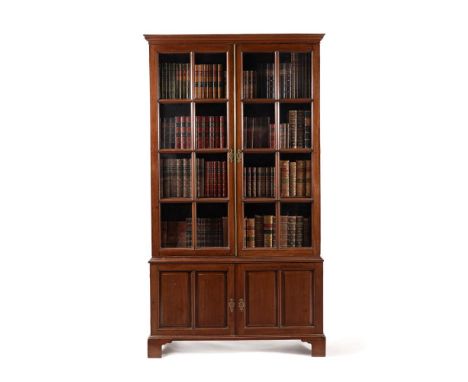

A MAHOGANY BOOKCASE'PEPYSIAN' TYPE, SECOND QUARTER 18TH CENTURY233cm high, 130cm wide, 45cm deepAn unusual feature of this bookcase is that the profile of the glazing bars of the upper section has also been used to bisect the panels of the lower section.The profile of the thick glazing bars also suggests dating the bookcase to the second quarter of the 18th century. The same profile of glazing bars is present to the windows of several Spitalfields houses of the period. In addition the use of mahogany is evident in the construction of the documented staircase at 4-6 Fournier Street, Spitalfields. Mahogany was also known to have been used at Houghton Hall and various churches at this early period.For further discussion and evidence of the early mahogany trade and use of the timber, See Adam Bowett, The English mahogany trade 1700-1793, thesis, 1996. This bookcase is similar in form to the 'Pepys Bookcase' first made by the Master Joiner Thomas Simpson (alias Sympson the Joiner) for the naval administrator and diarist Samuel Pepys to house his vast collection of books at his residence at Seething Lane, London. It is possible that Pepys himself had a hand in the design of the original bookcase. For a related example of bookcase, see Adam Bowet, Early Georgian Furniture 1715-1740, Antiques Collectors Club, 2009, page 133, plate 3:75. Condition Report: Marks, knocks, scratches and abrasions commensurate with age and use. Old splits and chips. Various losses to the putty securing the glazed panels. Locks and catches appear original. Key present and operates both locks. Escutcheons are period replacement. Some small filled holes are visible from previous escutcheons. Two escutcheons are lacking some of their securing pins but remain firmly in position. Hinges are old replacements. Small fillets of timber have been applied adjacent to them to fill the gap from the previously larger hinges. The screws securing the hinges have been 'overdriven' in places resulting in the tips of the screws poking out of the sides of the bookcase. Some small filled holes are also visible to the front of the doors adjacent to the hinges. Some old vertical splits and cracks to backboards. Evidence of old worm. Later securing blocks to backs or feet are detached, three are present. One rear foot with detached rear facet.Please refer to additional images for visual reference to condition. Condition Report Disclaimer

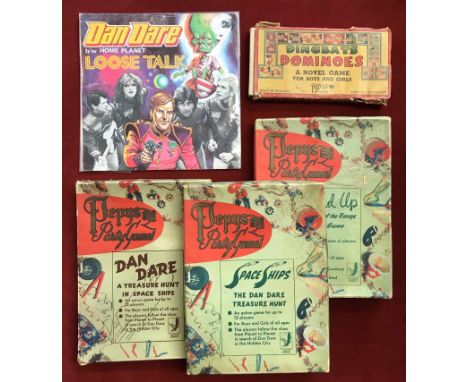

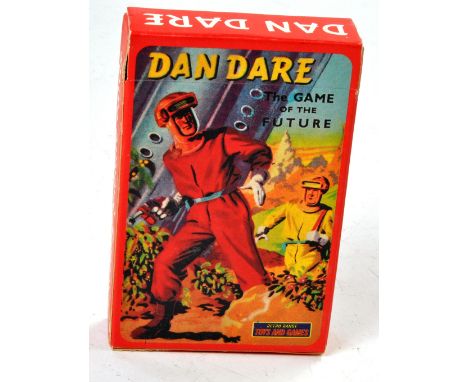

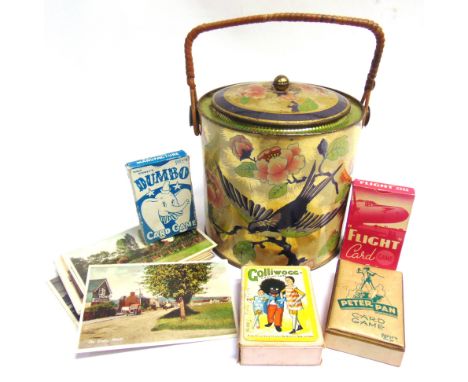

ASSORTED COLLECTABLES comprising a Vincents Chocolate Toffees tin in the form of a biscuit barrel, 18cm high; Golliwogg card game, by Thomas de la Rue, circa 1908, boxed (complete at 48 cards); Pepys Walt Disney Dumbo card card, boxed (complete at 45 cards); Pepys Peter Pan card game, boxed (complete at 45 cards); Flight card game, boxed (complete at 44 cards); and approximately fifty-eight assorted postcards.

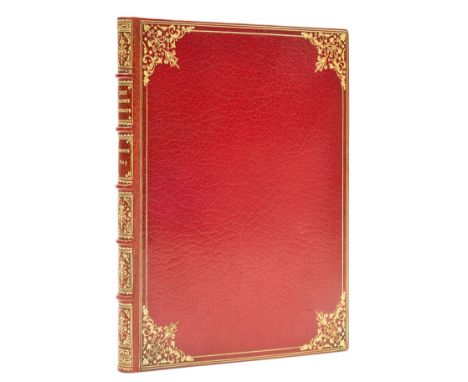

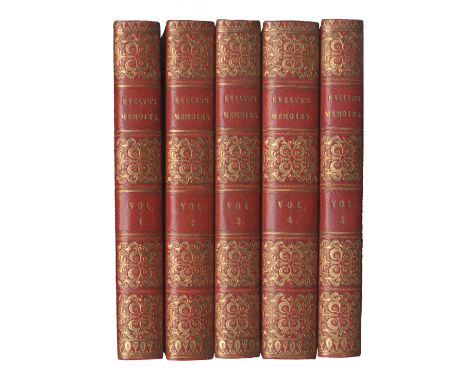

BINDINGSEVELYN (JOHN) Memoirs, 5 vol., edited by William Bray, Henry Colburn, 1827--COCKBURN (HENRY) Memorial of His Time, 3 vol., Edinburgh, A. & C. Black, 1827--PEPYS (SAMUEL) Everybody's Pepys... illustrations by Ernest H. Shepard, G. Bell, 1927--CHESTERTON (G.K.) The Father Brown Stories, Cassell, [1955]--WAUGH (EVELYN) Officers and Gentlemen, 1955; Men at Arms, 1952; Unconditional Surrender, 1961, Chapman and Hall, red half morocco gilt--CORYAT (THOMAS) Coryat's Crudities, 2 vol., later full red calf, Glasgow, Maclehose, 1905--HEBER (REGINALD) Narrative of a Journey through the Upper Provinces of India, 3 vol., second edition, wood-engraved plates, contemporary calf, John Murray, 1828--DRUMMOND (WILLIAM) The Oedipus Judaicus, [LIMITED TO 50 COPIES], 16 lithographed plates, light spotting, bookplate of Laurence Currie, early mottled calf gilt, A.J. Valpy, 1811--GREEN (J.R.) A Short History of English People, 4 vol., contemporary half calf gilt, Macmillan, 1898, 8vo; and a large quantity of others, including approximately 90 bound in half morocco, calf, etc. (quantity)Footnotes:Provenance: The Library of the late A.J. Karter.This lot is subject to the following lot symbols: •• Zero rated for VAT, no VAT will be added to the Hammer Price or the Buyer's Premium.For further information on this lot please visit Bonhams.com

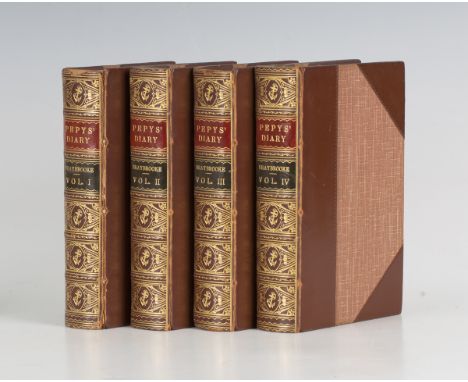

BINDINGS. - Samuel PEPYS. Diary and Correspondence… with a Life and Notes by Richard Lord Braybrooke. London: H.G. Bohn, 1858. 4 vols., sixth edition, 8vo (177 x 114mm.) Numerous engraved plates. (Mild toning.) Later brown half calf bound by Bayntun (Rivière) with red and green morocco lettering pieces to the second and third compartments of the spine, gilt anchors with densely in-filled surround to the rest, t.e.g. (occasional rubbing). - And a further twenty-five leather-bound literary volumes (including, in contemporary tree calf, the Dublin printing of 'The Works of Samuel Johnson', 6 vols., 1793, 8vo) (29).Buyer’s Premium 24.5% (including VAT @ 0%) of the hammer price. Lots purchased online via the-saleroom.com will attract an additional premium of 5% (including VAT @ 0%) of the hammer price.

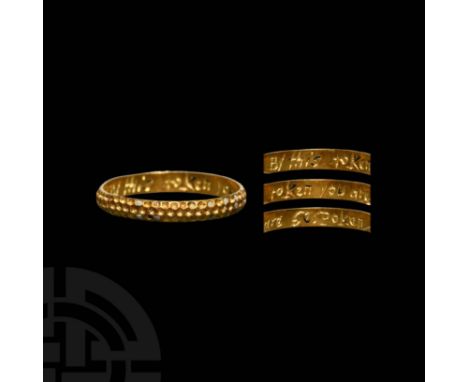

18th century AD. A gold D-section band, the external face ornamented with three circumferential rows of fine dimples, the interior inscribed 'By this token you are bespoken' in script characters. See Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.28, for this posie, sourced from 'The Best and Compleatest Academy of Compliments yet extant. Being wit and mirth improv'd by the most elegant expressions used in the art of courtship...' London, printed and sold by William Dicey, 1750; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. LON-AA2432, for a worn ring which appears to have three rows of dimples also, dated 16th-17th century AD. 1.20 grams, 18.10mm overall, 16.44mm internal diameter (approximate size British J 1/2, USA 5, Europe 9.32, Japan 9) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Fine condition.

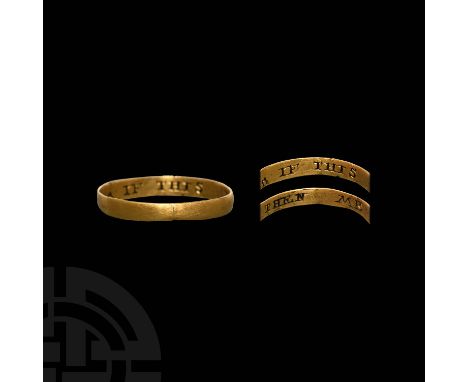

16th-17th century AD. A slender gold D-section annular band with plain outer face, the inner face inscribed 'IF THIS THEN ME' in seriffed capitals with small quatrefoil before; remains of niello fill. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.51, for the same inscription, 'me' spelt 'mee'; cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.413, for this inscription with spelling variation, dated 17th-18th century; museum number AF.1286, for this inscription with spelling variation, dated 16th-17th century AD; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id.LVPL-AD7284, for similar, dated 1550-1650; id. 1.12 grams, 17.40mm overall, 16.23mm internal diameter (approximate size British K, USA 5 1/4, Europe 9.95, Japan 9) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. Capital letter inscriptions are thought to have been more common before the mid 17th century AD, when inscriptions in italic script gained popularity. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Fine condition.

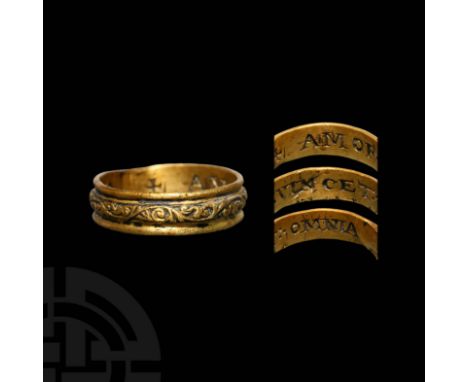

16th-18th century AD. A gold ring with D-section band, two slender c-section circumferential channels to top and bottom of external face, framing a foliate frieze with remains of niello inlay; Latin inscription to the inner face in seriffed capitals: '+ AMOR VINCET OMNIA' ('Love Conquers All'), the words separated by triangles composed of three dots. See Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p1. for this inscription and for multiple variations on the 'Amor Vincit' posie; cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.460, for a different ring with the same inscription and very similar lettering and punctuation, dated 16th-early 17th century AD.; cf. The Portable antiquities Scheme Database, id. YORYM-B0EB9B, for a very similar ring with the same posie, dated 1500-1700 AD; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. GLO-55A844, for a very similar ring design, dated 1650-1740 AD. 3.34 grams, 18.61mm overall, 16.02mm internal diameter (approximate size British K, USA 5 1/4, Europe 9.95, Japan 9) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. 'Amor Vincit Omnia' was perhaps the most popular 'stock' motto engraved onto posy rings bearing Latin inscriptions; it was the motto engraved on a brooch worn by the flirtatious Prioress in Chaucer's Prologue to the 'Canterbury Tales', penned around 1390 AD. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Fair condition.

18th century AD. A gold ring with hoop carinated around the internal face, bezel formed as twin heart-shaped cells set with turquoise coloured glass and garnet, gadrooning to the undersides, the external face of the hoop with French inscription in reserved seriffed capitals: 'MOI SEUL EN . AI . LA CLEF', ('I alone hold the key'), the words punctuated by clusters of decorative vertical notches; remains of niello infill around the lettering. Cf. The British Museum, museum numbers AF.1669 and AF.1641, for a very similar style of ring; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. HESH-4BDAD2, dated 1750-1900, for a similar style with a single heart-shaped cell. 0.97 grams, 17.34mm overall, 14.51mm internal diameter (approximate size British H, USA 3 3/4, Europe 6.18, Japan 6) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Fine condition.

18th century AD. A substantial gold D-section annular band with plain external face, internal face inscribed: 'loVe For EVer' in mixed script and capital characters. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.72, for this inscription; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id.GLO-9143B6, for a similar ring with the same inscription and script, dated c.1650-1850 AD and BH-5C4EAE, for a similar ring with same inscription and similar script dated 1600-1710 AD; cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.309, for a similar ring with the same inscription in a later script, dated 19th century AD. 5.20 grams, 21.84mm overall, 19.31mm internal diameter (approximate size British R, USA 8 1/2, Europe 18 3/4, Japan 18) (1"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition, slightly misshapen. A large wearable size.

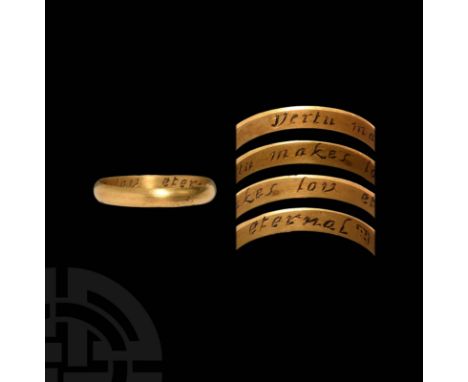

18th century AD. A gold D-section annular band with softly facetted outer face, inscription to the inner face reads 'Vertu makes lov[e] eternal' in script characters, followed by a conjoined 'RH' maker's mark in a rectangular cartouche; remains of niello inlay. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.105, for this inscription; cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.452, for a similar ring and maker's mark, maker unknown, dated 17th-18th century AD; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. SF-0A94B5; PAS-B622E7, for similar rings with the same inscription, albeit with variations in spelling, dated 1600-1799 AD. 2.13 grams, 19.73mm overall, 17.72mm internal diameter (approximate size British O 1/2, USA 7 1/4, Europe 15.61, Japan 15) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. No recorded conjoined 'RH' maker for this period, only for the 16th and very early 17th century AD. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition, a few small nicks.

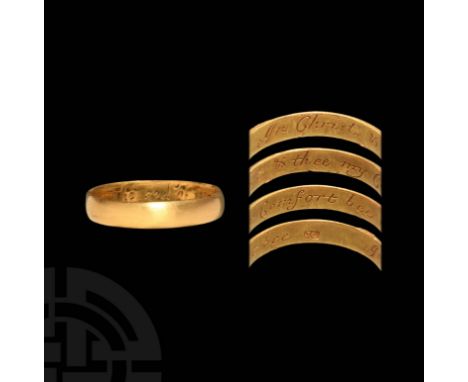

18th century AD. A substantial gold D-section annular band with plain external face, the interior inscribed: 'In Christ & thee my Comfort bee' in script characters, together with a maker's mark 'JC' in a rectangular cartouche. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, p.57, for this inscription; cf. The British Museum, museum numbers 1961,1202.329; AF.1346; AF.1353, for posy rings with the same maker's stamp, dated circa late18th century AD. 5.34 grams, 22.37mm overall, 18.92mm internal diameter (approximate size British R 1/2, USA 8 3/4, Europe 19.38, Japan 18) (1"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985; bought at the Cumberland coin fair, London, believed to have been found in Hertfordshire, UK. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition, a few small scuffs. A large wearable size.

Dated 1 January [1]709 AD. A D-section gold annular finger ring with floral and foliate ornament to outer surfaces showing traces of black enamel background; the inner face engraved in script 'Sr T Littleton Bar ob 1 Jan [1]709 aet 62' and with punched 'IB' maker's mark, possibly for the London maker J. Burridge who was active at this period. See Dictionary of National Biography, pp.1255-1256, for biographical summary; see Morant, P., The History and Antiquities of the County of Essex, Colchester, 1768, p.103; see Chancellor, F., The Ancient Sepulchral Monuments of Essex, London and Chelmsford, 1890, p.186, for details of his memorial and arms. 6.55 grams, 21.66mm overall, 17.84mm internal diameter (approximate size British O, USA 7, Europe 14.98, Japan 14) (1"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985; acquired at an antiques fair, believed to have been found in Essex, UK; this lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by AIAD certificate number no.10956-179120. Sir Thomas Littleton, 3rd Baronet, Stoke St Milborough (Shropshire) and North Ockendon (Essex), also known as Sir Thomas Poyntz (or Pointz), circa 1647-1 January 1709 (Julian calendar or 1710 Gregorian calendar), was born as second son to the 2nd Baronet but, after the early death of his older brother, he inherited the title and attended St Edmund Hall, Oxford, matriculating in 1665 and entered the Inner Temple in 1671; he was elected to the Convention of 1689 for Woodstock and served as Member of Parliament for several seats until his death. In 1697 he became Lord of the Admiralty and had acted as pallbearer at the funeral of Samuel Pepys, his predecessor; in 1698 he was elected Speaker of the House of Commons, later becoming Treasurer to the Navy, a post he held until his death. Although married, he had no children and the title became extinct upon his death. His memorial may be seen to this day in the church of St Mary in North Ockendon, Essex and is described by Chancellor who also gives details of the combined arms of Sir Thomas as: quarterly 1 and 4, argent a chevron. between three escallops sable, 2 and 3 'Pointz', within a mullet sable for difference; overall the Badge of Baronetcy and an inescutcheon gules and chevron ermine between three garbs or. Crest a Moor's head in profile couped at the shoulder proper wreathed about the temples argent and sable and a copy of a contemporary engraved portrait is included, together with extracts from other documentary references. Published sources give the year of his death as either 1709 (as on this ring) or 1710; this results from the changeover from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian in 1752; under the Julian calendar, the new year occurred 1 March, giving his death taking place in 1709; from 1752, the new year was pushed back to 1 January, resulting in his death year becoming 1710 under the new calendar rules. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Fine condition.

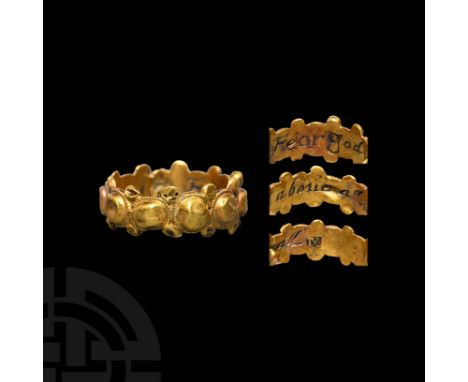

Mid 16th-early 18th century AD. A gold band ornamented with a circumferential frieze of oval bosses to the external face, faux ropework borders around, smaller domed pellets between to the top and bottom edges; the interior inscribed in italics: 'Fear god above all' in cursive script, partial remains of niello inlay, followed by stamped maker's mark 'IY[or V]' in rectangular cartouche, possibly that of John Young entered in 1760 and in use until at least 1793. Cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id.NMS-B8BCC4; BERK-118101; LIN-B6F8A3; SOM-823925; SF-3A8B11, for very similar with different inscriptions dated c.1550-1700; See Oman (1974, plate 58 c, p. 111) for a very similar example with a different inscription, dated to the early 17th century; cf. The British Museum, museum number 1942,0708.1, for broadly similar, different inscription. 2.77 grams, 18.83mm overall, 15.44mm internal diameter (approximate size British I, USA 4 1/4, Europe 7.44, Japan 7) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Fair condition.

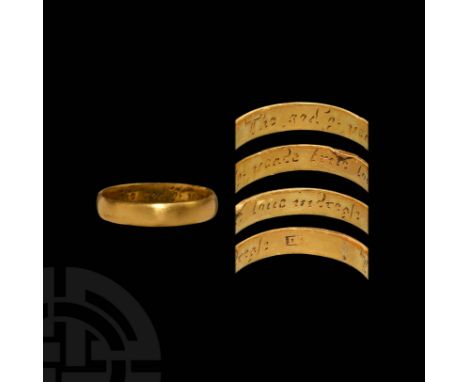

18th century AD. A gold D-section annular band with plain external face, the internal face inscribed: 'The god of peace true love increase' in script characters with remains of niello inlay; stamped with maker's mark 'IV' in rectangular cartouche, likely for the maker John Vickerman. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, p.95, for this inscription; cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1376, for a similar ring with this inscription, by another maker, and museum number AF.1375, for a similar ring with this inscription and date; museum number AF.1215, for the same maker's mark on a gold posy ring. 4.42 grams, 21.75mm overall, 19.33mm internal diameter (approximate size British S 1/2, USA 9 1/4, Europe 20.63, Japan 19) (1"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. John Vickerman's known active dates are 1768-1773 AD. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition, small scuffs at edge. A large wearable size.

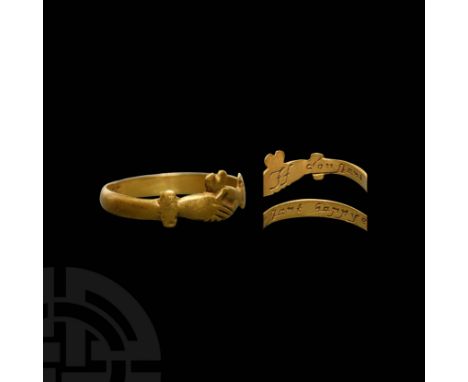

18th century AD. A gold posy or fede ring with D-section band, bezel formed as two clasping hands emergent from sleeve cuffs, a heart between above, with worn detailing to the hands and cuffs; the interior inscribed 'If constant happye' in script characters. Cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.269, for very similar ring, different inscription, with known maker dated 17th century; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. PAS-FB4D00, for similar fede design, dated 1650-1720. 1.44 grams, 18.00mm overall, 16.80mm internal diameter (approximate size British K, USA 5 1/4, Europe 9.95, Japan 9) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition. Rare.

18th century AD. A gold D-section annular band with plain exterior, inscription to internal face: 'We rest Content' in cursive script. Cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.92, for a ring of similar style with similar inscription content and script-'With one Consent wee rest Content', dated 17th-18th century AD, donated by Dame Joan Evans; see Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.110, for the BM's example. 4.53 grams, 20.10mm overall, 17.72mm internal diameter (approximate size British O 1/2, USA 7 1/4, Europe 15.61, Japan 15) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition, slightly misshapen.

18th century AD. A gold D-section annular band with plain outer face, the internal face inscribed 'God alone made us one' in script characters, followed by stamped maker's marks 'MS' in blackletter and 'St' closely stamped in two rectangular cartouches. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.39, for this inscription; cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1239, for a similar ring with this inscription, dated 17th century AD; see The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, IOW-6C0F12, for a gold posy ring also stamped with 'MS' in blackletter script, dated 1613-1733 AD. 4.97 grams, 18.07mm overall, 15.08mm internal diameter (approximate size British H 1/2, USA 4, Europe 6.81, Japan 6) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition.

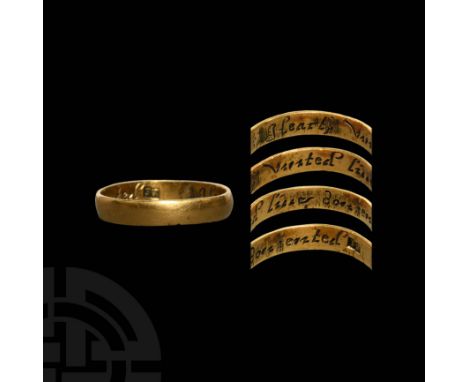

18th century AD. A gold D-section annular band with plain external face, the interior inscribed: 'Hearts united live contented' in script characters, followed by maker's mark 'IV' in rectangular cartouche, probably for John Vickerman. Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, 1931, p.47, for this inscription; cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1270, for a similar ring with this inscription, dated 18th century; museum number AF.1269, for a similar ring with this inscription dated 17th-18th century AD; museum number AF.1215, for a gold posy ring with the same maker's mark, dated later 18th century AD; cf. The Fitzwilliam museum, PER.M.324-1923, for a ring with this inscription, undated. 3.58 grams, 21.50mm overall, 18.90mm internal diameter (approximate size British R 1/2, USA 8 3/4, Europe 19.38, Japan 18) (1"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardised spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition, a few nicks. A large wearable size.

14th-15th century AD. A gold flat-section annular band, engraved around the exterior with stylised flower-and-sprig ornament alternating with French blackletter inscription: 'ma ioie', meaning 'my joy'. Cf. The V&A Museum, accession number 7125-1860, for a similar ring type. 1.41 grams, 16.79mm overall, 15.69mm internal diameter (approximate size British I 1/2, USA 4 1/2, Europe 8.07, Japan 7) (3/4"). From the Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK; acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985. The ring is almost certainly of English manufacture and inscribed in the variety of Anglo-French normal for such amatory inscriptions in the late Middle Ages. A 15th century silver thimble bearing the same inscription was sold at Christie's on 31 May 1995, lot 206, while a contemporary ring-brooch in the British Museum reads 'vous estes ma ioy moundeine [you are my earthly joy]'. ‘Posy’ is derived from ‘poesy’ or ‘poetry’, with posy rings being named thus in the mid 19th century. Prior to this date, there was no specific term for these rings. In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty. [A video of this lot is available to view on Timeline Auctions Website] [No Reserve] Very fine condition.

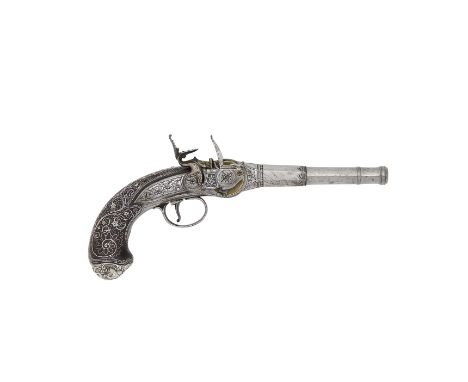

A Very Rare 54-Bore Flintlock Rifled Breech-Loading Repeating Magazine Pistol On The Lorenzoni PrincipleBy Grice, London, Indistinct Birmingham Silver Hallmarks, Maker's Mark Of William Grice, Circa 1780With three-stage cannon barrel turned at the muzzle and rifled with eight spiral grooves, octagonal breech with fluted girdle, engraved 'LONDON' on a foliate scroll along the top flat and with a band of beadwork at the rear, border engraved rounded action and bevelled back-action lock, the former finely decorated with rocailles and foliage, and with a basket of flowers forward of the grooved gas-escape, the latter signed on a foliated scroll, later crude cock automatically cocked via a flat bar on the inside engaging with the circular brass breech-block and operated by the curved side-lever with button terminal, hinged priming magazine cover with spring catch and engraved with a flower (steel-spring missing), hinged border engraved magazine cover for balls on the left decorated en suite with the action and with sprung button catch, steel trigger-guard engraved with a foliate rocaille on the bow, figured swelling rounded butt profusely inlaid with fine symmetrical silver wire scrollwork and engraved silver flower-heads issuing from a basket above a silver wire oval, and involving a rocaille on each side, cast and chased silver lion and rampart butt-cap within a border of rocailles, and in fine condition 11.5 cm. barrelFootnotes:The maker is William Grice (1766-90) recorded working at 5 Sand Street, Birmingham between 1774 and 1781 following which date he was in partnership with Joseph Grice (1782-1797) at the same address. He died on 25 July 1790. It is most unusual to find a gunsmith with a registered silver mark as a small workerFor an unsigned example, Birmingham hallmarked for 1785, see The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Early Firearms of Great Britain and Ireland from the Collection of Clay P. Bedford, 1971, pp. 122 and 125, no. 129. See also a related rifle formerly in the W. Keith Neal Collection and sold in these Rooms, Antique Arms and Armour, 4 April 2007, lot 371Although the breech-loading magazine system employed is usually termed the 'Lorenzoni System' after the Florentine gunmaker Michele Lorenzoni, it is not certain to which European gunmaker the credit for its invention should be given. A much quoted reference to the system in the diaries of Samuel Pepys dates back to 1662. On 3 July he refers to a 'gun to discharge seven times, the best of all devices I ever saw, and very serviceable, and not a bauble, for it is much approved of, and many made thereof'. Despite this eulogy the incidence of explosion in the powder magazines probably explains the great rarity of such firearms todayFor further information on this lot please visit Bonhams.com

MINIATURE FURNITURE - A carved walnut armchairpossibly late 17th/early 18th century in the Charles II styleThe frames carved with scrolled acanthus foliage and flowers, the crest rail and fore rail each carved with a Royal crown, with spiral twist-turned stiles, conforming arm terminals and foliate wrapped scrolled arm supports, on ring turned block-and-baluster legs, stamped several times: 'T.I.', 21cm wide x 23cm deep x 50cm high, (8in wide x 9in deep x 19 1/2in high)Footnotes:The offered lot has featured twice on the renowned BBC television program, 'Antiques Roadshow'. The present chair was first inspected on 15 June 1994 and then also subsequently appeared for a second time on 9 July 2019. Copies of this 'Antiques Roadshow' paperwork are available for inspection upon request. Although chairs of this scale have often been cited erroneously as 'apprentice pieces', the existence of two beech armchairs of this scale in The V&A Museum collection, with their accompanying late 18th century wooden dolls, makes the case for these 'miniature chairs' being intended for use as 'toys' all the more likely. The V&A examples (T.846Y-1974 and T.846V-1974) which accompany the celebrated Lord and Lady Clapham dolls (circa 1690-1700) follow the pattern of full sized chairs of the period. The chairs would almost certainly have been made by a professional chair maker and the construction techniques mirror those found on full sized examples from the period. The scarcity of surviving late 17th century dolls, although many were produced, may well reflect the few surviving miniature chairs. Other surviving period miniature chairs, including one of the 'Clapham' chairs are in poor condition implying the likelihood of them having been played with and hence the few surviving examples.The Lord and Lady Clapham dolls are thought to have belonged to the Cockerell family who were descendants of Samuel Pepys. Pepys' nephew John Jackson married a Cockerell and the dolls were named 'Lord' and 'Lady' of the family home in Clapham. The remarkable condition of the Clapham dolls suggests that in this instance they may have been admired by adults rather than being played with by children and were viewed more as decoration for the home.For further information on this lot please visit Bonhams.com

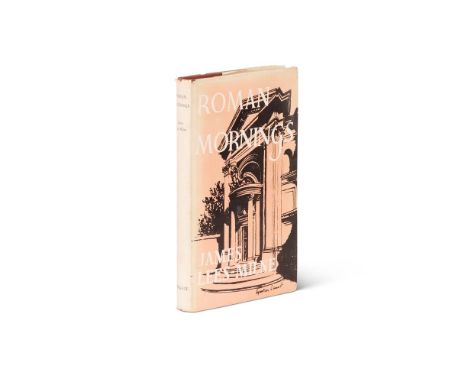

Ɵ LEES-MILNE, James. (1908 - 1997). Roman Mornings. Author's Presentation copy to Sacheverell and Georgia Sitwell. London: Alan Wingate, (1956). single volume, first edition, 8vo. (223 x 145mm), publisher's burgundy cloth, gilt lettering to spine, dustwrapper unclipped, illustration after Lynton Lamb, inscribed and dated by the author in black ink to front free e/p., 'To Sachie & Georgia, / with much affection from / Jim, 26.5.56', title in red and black, half-title, dedicated to Sacheverell, 'To Sacheverell Sitwell who looks at architecture with the eye of a poet', 13 plates, (including frontispiece). The author's fourth book.(George) James Henry Lees-Milne was a British architectural historian, novelist and biographer. His extensive diaries have been compared with that of Samuel Pepys and hailed as 'a treasure of contemporary English literature'. Lees-Milne was friends with many prominent intellectual and social figures of his day. In 1951 he married Alvilde, Viscountess Chaplin, a prominent gardening and landscape expert. Both were bisexual. Alvilde is reputed to have had lesbian affairs with Vita Sackville-West, and others.Provenance: The Library of Dame Edith Sitwell.(Qty. 1)

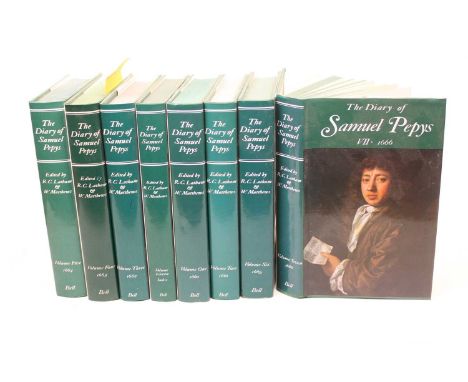

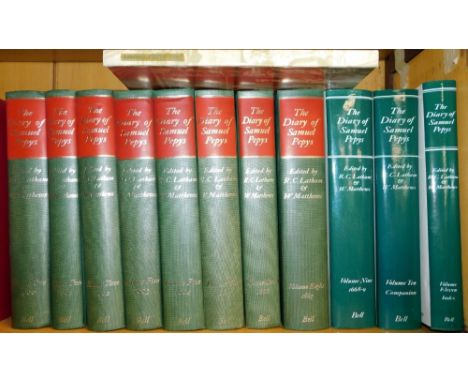

Mavrogordato (J. G.). A Hawk For The Bush, a treatise on the training of the sparrow-hawk and other short-winged hawks, 1st edition, London: H. F. & G. Witherby, 1960, 8 colour & monochrome plates, some minor marginal toning, original cloth in dust jacket, small puncture mark to the head of the front cover, 4to, together with; Snowden Gamble (C. F.), The Story of a North Sea Air Station, 1st edition, Oxford: University Press, 1928, numerous monochrome illustrations & plates, some light toning & minor spotting, original cloth in dust jacket, covers toned, marked & rubbed to head & foot with some minor loss, 8vo, plus Hamilton, Adams, & Co. [publisher], The Full Proceeding of the General Court Martial, held at Cork Barracks...when Captain Augustus Wathen, of the Fifteenth, or King's Hussars, was tried...by his commanding-officer, Lieut.-Colonel Lord Brudenell, London, 1834, 187 pages, bookplate to the front pastedown, some marginal toning, contemporary green cloth, front board partially detached, boards & spine rubbed, slight loss to the paper spine label, 8vo, and Murakami (Haruki), Kafka On The Shore, limited edition, London: Harvill Press, bookplate signed by the author to the limitation page, publishers original white cloth in slipcase, 8vo, 663/1000, plus other miscellaneous modern literature & reference, including The Diary Of Samuel Pepys, 11 volumes, edited by Robert Latham & William Matthews, London: Bell & Hyman, 1970-83, 8vo, many original cloth in dust jackets, some paperback editions, G/VG, 8vo/4toQty: (6 shelves)

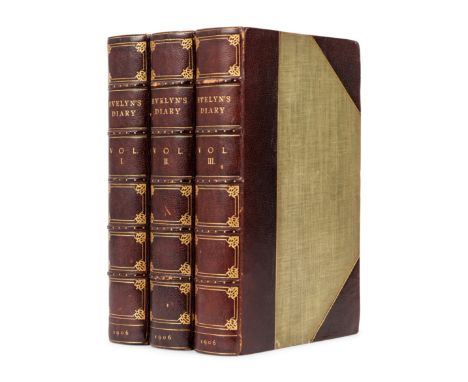

EVELYN, John (1620-1706). The Diary of John Evelyn. Austin DOBSON, introduction. London & New York: Macmillan and Co., Limited & The MacMillan Company, 1906. 3 volumes, 8vo (221 x 140 mm). Engraved portrait frontispieces, titles printed in red and black, 11 engraved portraits, 3 engraved maps (1 folding), 38 engraved views (2 folding), 3 facsimile title-pages, one folding facsimile autograph letter, one folding pedigree of the Evelyn family. (Some offsetting, some staining to preliminary leaves, occasional light spotting.) Contemporary half morocco, green cloth gilt, top edge gilt, others uncut (spines sunned, some light chipping or staining). LIMITED EDITION, one of 100 unnumbered copies of the "Edition de Luxe." Evelyn's diary was first published in 1818 and was immediately well-received. While the publication of Samuel Pepys ' diary a few years later became more widely known, the publication of The Diary of John Evelyn paved the way for Pepys ' success (Harris and Hunter, John Evelyn and His Milieu, 2003, p. 2). Property from the Collection of Norman and Florence BlitchFor condition inquiries please contact lesliewinter@hindmanauctions.com

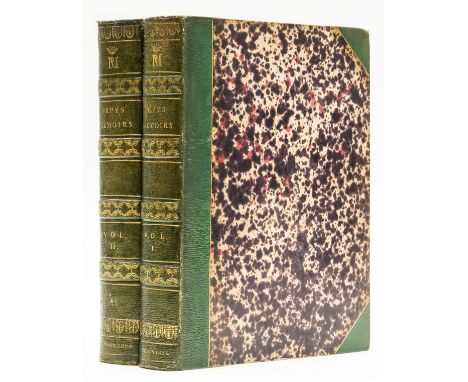

Pepys (Samuel) Memoirs of ... comprising His Diary from 1659 to 1669 ... and a selection from his Private Correspondence, 2 vol., first edition, without half-titles, engraved portrait frontispiece, 7 engraved plates, 2 tables, 1 facsimile, 1 double-page map, off-setting, occasional spotting, contemporary half-straight grain morocco, gilt, a little rubbed, 4to, 1825.

Football Card Collection + Memorabilia: 5 FKS Soccer Stars albums which appear to be nearly complete on most, 2 x early 70s Sun sticker books, Very old Football Whist game by Pepys, Squad signed A4 pages from the 90s of Bury Wycombe Southampton and Falkirk, Albums giveaways from football magazines, Pre War complete sticker albums to include one of football, England 82 World Cup record, Pre War boxing annual and lots more.

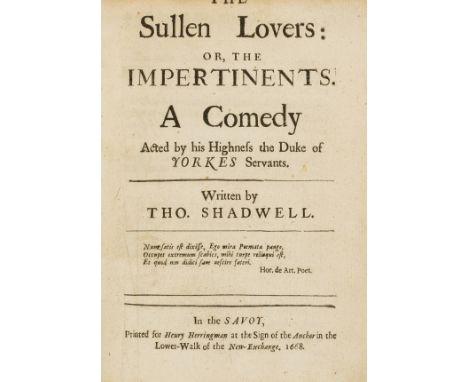

Shadwell (Thomas) The Sullen Lovers: or, the Impertinents. A Comedy, first edition of the author's first book, trimmed at upper edge affecting first word of title and several headlines and pagination occasionally, inner margin of final leaf defective, just touching one letter of text, modern full red morocco by Riviere & Son, spine slightly sunned and extremities very slightly rubbed, inner gilt dentelles, g.e., [Wing S2878], 4to, In the Savoy, Printed for Henry Herringman, 1668.⁂ Based on Moliere's Les Facheux. Shadwell's wife starred in the first production. Samuel Pepys' diary entry for Saturday 2 May, 1668 reads: "...and thence to the Duke of York's playhouse, at a little past twelve, to get a good place in the pit, against the new play, and there setting a poor man to keep my place, I out, and spent an hour at Martin's, my bookseller's, and so back again, where I find the house quite full. But I had my place, and by and by the King comes and the Duke of York; and then the play begins, called "The Sullen Lovers; or, The Impertinents," having many good humours in it, but the play tedious, and no design at all in it. But a little boy, for a farce, do dance Polichinelli, the best that ever anything was done in the world, by all men's report: most pleased with that, beyond anything in the world, and much beyond all the play."

Duelling.- James I (King of England) A Publication of His Ma'ties Edict, and Severe Censure against Private Combats and Combatants, first edition, initial leaf (blank except for signature 'A') present, woodcut decorations, woodcut arms to title verso, first and last leaf slightly soiled, early 20th century red crushed morocco, gilt, by Riviere & Son, g.e., [STC 8498], 4to, by Robert Barker, 1613.⁂ This issue with 'doth' (not 'doeth') reading in line 1 on A3 verso. Signature of Roger Pepys to title - presumably Roger Pepys (1617-88), the cousin of diarist Samuel Pepys, lawyer and MP (1661-78).

English school (early 18th century)Portrait of Dickson Downing wearing powdered wig, white cravat and buttoned pale blue jacket, inscribed 'Dickson Downing Esq.' 1728, oil on canvas, 73 x 61cm, in period gilt frame Dickson was the son of Richard Downing and Elizabeth Dickson (he was her second husband) and grandson of Maj Downing of the Guards, who was mentioned in Pepys Diary in 1666 as Capt Downing. Dickson married Bridget Baldwin and their son (Rev) George was Prebendary of Ely Cathedral who married Catherine Chambers, daughter of Nathaniel Chambers, barrister-in-law

-

1821 item(s)/page

![[Folio Society] Shakespeare's Romeo & Juliet; Hamlet; King Richard II; Antony & Cleopatra and Julius Caesar (5 volume](https://cdn.globalauctionplatform.com/653c5cde-4c3a-4e6f-98f3-adec00b5bd90/dffad8de-a767-4a64-864c-ae0100deba5c/468x382.jpg)

![[AP] A TROOPER~S SWORD OF THE EARL OF OXFORD~S REGIMENT OF HORSE, LATER THE ROYAL HORSEGUARDS (THE BLUES), LAST QUARTER OF TH](https://cdn.globalauctionplatform.com/5810e383-7ca3-4676-b7c8-ade200b9947a/af063543-7d75-4467-a859-ade200c3f48b/468x382.jpg)

![Dated 1 January [1]709 AD. A D-section gold annular finger ring with floral and foliate ornament to outer surfaces showing tr](https://cdn.globalauctionplatform.com/3ae71d3e-8613-4112-af58-adc600fd85ab/28ef1b0c-1cd5-4c8d-ac65-adc6010c65a4/468x382.jpg)