We found 3059 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 3059 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

3059 item(s)/page

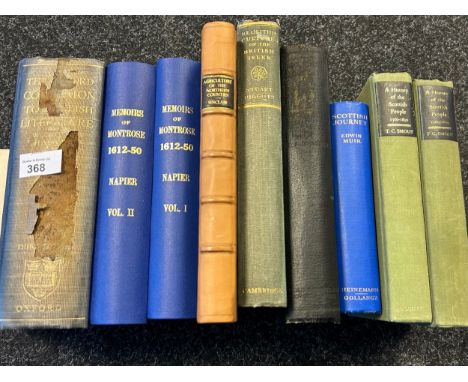

A collection of historical books to include history of the Scottish people Vol 1&2, by Snout. T.C - London 1969, The Neolithic cultures of the British Isles by Piggott, Stuart - Cambridge 1954, Early Irish history and Mythology by O'Rahilly, Thomas - Dublin 1946, Memories of Montrose Vol 1&2 by Edinburgh MTCCCLVI. Please see images for further titles.

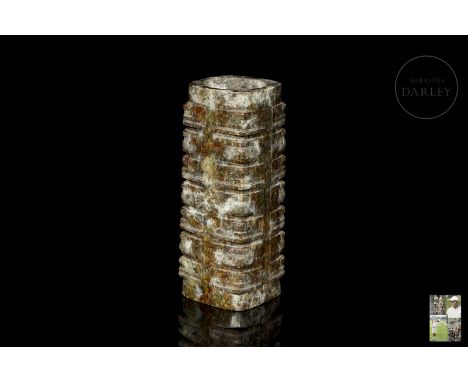

Beautiful greenish jade, with reddish, ochre and amber flecks. Carved in the traditional ‘cong’ shape, with a rectangular exterior with horizontal bands in relief and a hollow cylindrical interior. The perimeter is finely decorated with incised borders. It shows age-related wear. Neolithic period (ca. 6000 - 2000 BC) or later. Size: 21.8 x 8.7 x 8.6 cmWeight: 2427 gProvenance: Collection of Tommy Lam, Hong Kong, from 1980.

Archaeology finds, Neolithic interest etc - to include a Danish (Nordic) flint polished axehead, light greyish-brown mottled creamy white in colour, 9cm. length; Danish polished flint axehead, caramel in colour, 5cm. length; Neolithic part axehead made from granite, probably Guernsey, greenish-grey, sharp cutting edge, 6.7cm. length; well-crafted tanged arrowhead with convex base, probably North American Indian, made from green coloured chert, 5.3cm. length. (4) * Accompanied by Guernsey Museums letter, explaining each piece.

Ilias Lalaounis, a pair of Neolithic horn earrings, hammered brushed finish, with clip fittings for non pierced ears, stamped A21 750 Greece, with makers mark Ilias Lalaounis and logo, one earring measures 5.4 x 3.7cm, in a Ilias Lalaounis red box Condition Report: Gross weight 33.5 grams Overall good conditionclips open and close securely and have silicon covers on

Artefacts, fossils and minerals (30 plus 23x small shark teeth). Noted 4x spinosaurus teeth; a Neolithic stone axe head (found in East Anglia); a couple of iron meteorites; a few pieces of amber, one with some tiny insect inclusions; half a megalodon tooth etc. Note the large flint axe head is of modern workmanship. Sold as seen.

A LARGE CHINESE NEOLITHIC PERIOD TWO-HANDLED OVIFORM JAR, 2650-2300 BC, probably Majiayao culture, Banshan phase, with tall neck and loop handles, painted in dark brown and dark red, with bands of linear and geometric ornament, 47cm highProvenance: Private German collection, formed in the 1960s. Purchased and housed by a British collector circa 1970s until now. Small chips and losses to the rim of the neck, some small possibly areas of in-filling to these chips and possibly to the handles, although there is nothing visible under UV, there is some typical wear and surface scratching to pigment, minor surface deterioration.

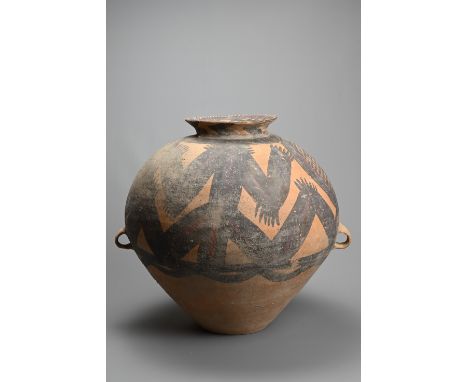

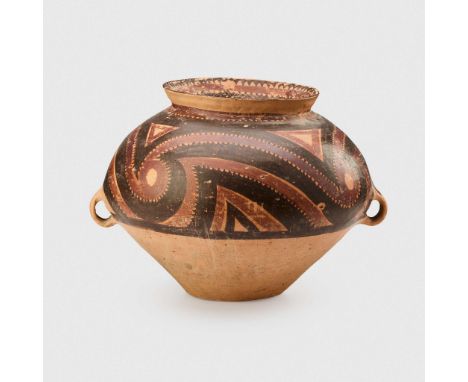

A CHINESE NEOLITHIC PERIOD POTTERY OVIFORM TWO-HANDLED JAR, circa 3300-2000 BC, possibly Majiayao culture, with loop handles and everted rim, painted in brown and dark red pigment with stylised figures and a circular diaper-pattern panel, 38cm highProvenance: Private German collection, formed in the 1960s. Purchased and housed by a British collector circa 1970s until now.Overall in good decorative order. Some typical surface wear and deterioration to pigment, although overall it is boldly decorated and much of the decorative remains. Some cracking and small losses to the neck, small areas of pitting and scratching to body overall.

A GROUP OF CHINESE POTTERY FIGURES, MODELS AND ASSOCIATED FRAGMENTS, PREDOMINATELY TANG DYNASTY (618-906). Comprising: a guardian earth spirit, enriched in red and white pigment approx. 56cm high, two models of terracotta horses, a large painted model of a court lady, probably Han Dynasty, approx. 52cm high, a straw-glazed model of a guardian spirit 36.5cm high, a rectangular section warmer, a small painted model of a standing court lady 24.5cm high, a Neolithic two-handled oviform vase painted in dark brown pigment with linear bands and scrolls, a Tang amber-glazed cylindrical jar incised with reeded bands, on scroll feet For the most part, the majority of items are extensively damaged and with losses, some of the associated fragments are present, but all require restoration. The neolithic vase is extensively broken and repaired, the amber glazed jar is lacking a foot, The small standing Tang court lady is in good order, other than the usual surface losses to pigment.

CHINESE NEOLITHIC "YANGSHAO" VASE CHINA, MAJIAYAO YANGSHAO CULTURE, C. 2300–2000 B.C. painted terracotta, brown and tan earthenware jar, the upper two thirds painted in black and red with a series of curved arcs 25cm tall Private collection, London, United Kingdom, acquired from the belowPeter Petrou, London The Yangshao culture and the following Majiayao culture (c. 5000–2000 B.C.) were Neolithic civilisations that flourished along the middle reaches of the Yellow River in China. Known for their early advancements in agriculture, these cultures practised millet farming and domestication of animals, supporting settled village life. Yangshao and Majiayao societies are particularly noted for their painted pottery, often featuring geometric and stylised motifs in black and red on buff-coloured earthenware. These ceramics, typically hand-built using coiling techniques, suggest a sophisticated aesthetic sensibility and possible ritual or symbolic significance.

AFRICAN NEOLITHIC GREEN FELSITE POUNDER TENERIAN CULTURE, CENTRAL SAHARA, C. 4TH – 2ND MILLENNIUM B.C. of narrow cylindrical shape with slightly pointed ends, on a bespoke black metal stand 51cm tall Private collection, Belgium, formed late 1960s – present The Tenerians, a people named for the Ténéré Desert, a stretch of the Sahara in Niger known to Tuareg nomads as a "desert within a desert", were in the region from 5200 B.C. E. to around 2500 B.C.E. This is one of the driest deserts in the world today, but archaelogical evidence confirms it hosted at least two flourishing lakeside populations during the Stone Age. The first culture appearing in the area 10 000 years ago were the Kiffians, hunter-fisher-gatherers whose large stature of up to 6 feet proves that food was abundant. The Sahara dried up around 7200 B.C., which caused the Kiffians to disappear. The arid period lasted roughly a millenia, after which the water returned, and with it a new population, this time the Tenerians. Based on skeletal evidence, they curiously seemed to have more in common with people living in the Mediterranean than neighbouring settlers in the Sahara. Around 2500 B.C., the onset widespread desertification of the Sahara ended the settlement in Gobero.

AFRICAN NEOLITHIC STONE CHOPPER TENERIAN CULTURE, CENTRAL SAHARA, C. 4TH – 2ND MILLENNIUM B.C. carved black stone, long cylindrical form with the striking surface worked to a sharp point, ribbed handle 42cm long Private collection, Belgium, formed late 1960s – present The Tenerians, a people named for the Ténéré Desert, a stretch of the Sahara in Niger known to Tuareg nomads as a "desert within a desert", were in the region from 5200 B.C. E. to around 2500 B.C.E. This is one of the driest deserts in the world today, but archaeological evidence confirms it hosted at least two flourishing lakeside populations during the Stone Age. The first culture appearing in the area 10,000 years ago were the Kiffians, hunter-fisher-gatherers whose large stature of up to 6 feet proves that food was abundant. The Sahara dried up around 7200 B.C., which caused the Kiffians to disappear. The arid period lasted roughly a millenia, after which the water returned, and with it a new population, this time the Tenerians. Based on skeletal evidence, they curiously seemed to have more in common with people living in the Mediterranean than neighbouring settlers in the Sahara. Around 2500 B.C., the onset widespread arification of the Sahara ended the settlement in Gobero.

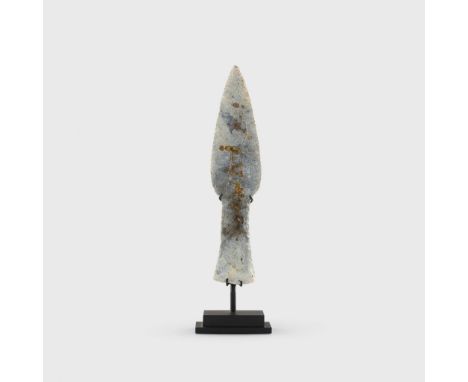

NEOLITIHIC FLINT DAGGER TYPE IV. NORTHERN GERMANY, C. 2000 - 1800 B.C. knapped grey flint, with an elongated leaf shaped blade and thin handle terminating in a fish-tail butt, raised on a bespoke mount 18.8cm high Private collection, northern GermanySubsequently part of a Belgian collection This fine blade is an example of the remarkable heights achieved by flint workers in late Neolithic Scandinavia and northern Germany. It dates to c. 2000 – 1800 B.C., aptly named the “Dagger Period”, an era where much of the rest of Europe had already adopted metallurgy. Though fashioned from flint, daggers such as these were inspired by contemporaneous European metal counterparts. During this period, Scandinavia lacked a sustainable supply of copper ore to support a metallurgical industry, so communities were traditionally thought to have lacked the ability, rather than the will, to produce copper daggers. However, recent studies have found that the delicate finishing could only have been completed with the aid of a metal-tipped tool. As such, it appears that the continued use of flint as a medium was made through choice as opposed to necessity. Indeed, even as bronze became very popular, the production of these beautiful flint daggers continued well into the Bronze Age.The common consensus is now that these daggers were a symbol of status. Used to demonstrate prestige or given as gifts. Microwear analysis on these items reveals that they were unlikely to have been used for practical purposes. Rather, the wear was found to be consistent with frequent removal from a protective sheath.They are widely considered to represent the very pinnacle of a European flint working industry that dated back tens of thousands of years.

AFRICAN NEOLITHIC GRINDING STONE CENTRAL SAHARA, C. 4TH – 3RD MILLENNIUM B.C. carved volcanic stone, worked into a deep crescent shape over years of use 43.7cm long Private collection, Belgium, formed 1960s – present 12,000 years ago, global climate shifts redirected Africa's seasonal monsoons northward, bringing rainfall to a vast expanse of the modern Sahara. This transformation led to the formation of lush watersheds spanning from Egypt to Mauritania, attracting diverse animal life and eventually human settlement. The present piece dates to around 6,000 - 5,000 years before the present day, when a people known as the Tenerian herded, hunted and cultivated crops beside great lakes amidst a savannah environment. The rains departed again around 2,500 B.C., and the Green Sahara became a desert once more, with only artefacts such as this grinding stone left to bear witness to the society which had once flourished.

NORDIC STONE BATTLE AXE SCANDINAVIA, NEOLITHIC PERIOD, C. 3RD MILLENNIUM B.C. carved stone, dual cutting edges featuring an elegant tapering form, with an off-centre circular perforation, the surface is smoothly finished with refined contours that emphasise its balanced proportions, raised on a bespoke mount 16.5cm long Private collection, Belgium The most significant weapons of Early Bronze Age Europe were not forged from metal but shaped from stone. These remarkable artefacts, in use for over a millennium, were wielded by peoples across a vast expanse from the Baltic to the Atlantic. Far more than mere tools, they were symbols of power, prestige, and cultural identity, their forms and craftsmanship attesting to the sophistication of their creators.They are most closely associated with the archaeological Corded Ware Culture, a society distinguished by its distinctive cord-impressed pottery, which flourished across much of northern and central Europe. Skilled farmers, traders, and warriors, the people of this culture left behind burial sites rich with evidence of complex social structures and belief systems. Among the first to adopt and spread the use of copper and bronze, the Corded Ware people marked a pivotal shift in European metallurgy. Yet, it is the stone battle axes that stand out as some of their most diagnostic objects.Diametrically aligned around a central perforation, these axe-hammers are finely sculpted, with intricate chiselled details that reveal an aesthetic intent behind their design. Among the most striking are the "boat-shaped" models, their sleek profiles reminiscent of Native American canoes (see lot 80), which are characteristic of the late Neolithic period.André Grisse argued these objects were crafted with geometric precision, based on metric standards. He observed: "These artefacts convey a spiritual and ideological message. Their forms, shaped by geometric and mathematical principles, reflect cultural connections across Europe from the late 6th millennium to the mid-3rd millennium B.C. They bore invisible geometric traces, suggesting their creators' advanced understanding of design and symbolism. Those who carried these objects were likely not just warriors but also scholars or astronomers, connected to earthworks."While their imposing forms may suggest a martial purpose, many clues point also to a ceremonial role. Though nothing can be said with absolute certainty about their use, the limited effectiveness of these axes as cutting tools combined with the significant effort required to produce them makes their function as everyday implements unlikely (though there is debate in this respect). Instead, their depiction on funerary stelae alongside warriors, coupled with the exceptional care in their craftsmanship, suggests they symbolised social status. Some examples may even have been influenced by the earliest copper axes emerging in southeastern Europe during the 5th millennium B.C., reinforcing their symbolic significance.So integral were these artefacts to local cultures that miniature versions were created, possibly for personal adornment or ritual use. In southern Sweden, such miniatures have been found in wetland deposits, likely offered as gifts to the watery realm, while in northern Germany, they appear in mortuary contexts linked to cremation practices. Interestingly, while full-sized battle axes are typically associated with male burials, smaller examples are found in contexts involving women and children, suggesting they may have held talismanic properties. Some miniatures display pounding wear on their edges, unseen on full-sized axes, hinting at their use as mortars, perhaps for grinding materials for rituals. These miniatures might even be precursors to Thor’s hammer pendants of the Viking Age.Though we must be cautious when drawing direct connections, there is a further intriguing link between these ancient stone battle axes and the mythological world of the Viking Age, particularly through language. The people of the Corded Ware Culture are believed to have spoken an early form of the Indo-European language family. The Old Norse word hamarr, which describes Thor’s hammer, carries a dual meaning, both "hammer" and "rock." It's Indo-European roots, signifying "pointed," "sharp," and "stone," connect Thor’s weapon to the same qualities embodied by the stone axes wielded by the Corded Ware peoples. This linguistic link suggests that the hammer, much like the stone axes, was seen not just as a tool, but as an object imbued with power and symbolism deeply tied to the natural and metaphysical world.These stone axes appear to have been passed down through generations, with the evidence shown in their wear patterns and reworked edges, indicating prolonged use and careful maintenance. Some axes show signs of resharpening or re-polishing, suggesting they were prized possessions, preserved and adapted for continued use. Their deposition in high-status burials hints at their role as cherished heirlooms, interred at significant moments - possibly the death of the final owner. Others were placed in liminal spaces, such as riverbanks, bogs, or hilltops, indicating they were offerings to mark transitions or connections between realms both physical and spiritual. In later centuries and millennia, the discovery of these stone battle axes often occurred during ploughing, particularly following storms, when the soil was disturbed and these ancient artefacts emerged. Their striking forms, coupled with this timing, led to their association with "thunderstones", a folkloric belief that such objects were remnants of thunderbolts hurled by gods or supernatural beings. In many European traditions, these axes were thought to possess protective or magical properties, guarding homes from lightning, evil spirits, or even the mischief of trolls and fairies.Originally symbols of power, these axes took on new meaning when they were rediscovered in fields, riverbanks, and other liminal spaces. This connection to celestial or magical power deepened their mystique, transforming them from simple tools into sacred relics. In this way, and in a manner that continues to resonate today, objects such as these have seen many lives, first as weapons, then as relics of forgotten pasts, and now as artefacts that continue to captivate and intrigue, bridging the ancient and the modern.Axelsson, B. & Christensen, P.G.R. (eds.) (2004) The Corded Ware Culture in the Neolithic of Europe: A Social and Economic Approach.Beauvarlet, M. (2000) La Hache de Pierre à Travers le Monde. Paris: Editions Errance.Garrow, D. and Wilkin, N. (2022) The World of Stonehenge. London: British Museum Press.

NEOLITIHC STONE "BOAT" AXE NORTHERN EUROPE, LIKELY SWEDEN, NEOLITHIC PERIOD, C. 3RD MILLENNIUM B.C. carved stone, with a sleek, elongated form tapering towards dual rounded cutting edges, a gently curved profile reminiscent of a boat with a central perforation, subtly recessed interior, the surface is smoothly finished with refined contours highlighting its symmetry, raised on a bespoke mount, centre marked ‘cc/70472’ 18cm long Private collection, BelgiumPublished:Beauvarlet, M. (2000) La Hache de Pierre à Travers le Monde. Paris: Editions Errance, p. 113 The most significant weapons of Early Bronze Age Europe were not forged from metal but shaped from stone. These remarkable artefacts, in use for over a millennium, were wielded by peoples across a vast expanse from the Baltic to the Atlantic. Far more than mere tools, they were symbols of power, prestige, and cultural identity, their forms and craftsmanship attesting to the sophistication of their creators.They are most closely associated with the archaeological Corded Ware Culture, a society distinguished by its distinctive cord-impressed pottery, which flourished across much of northern and central Europe. Skilled farmers, traders, and warriors, the people of this culture left behind burial sites rich with evidence of complex social structures and belief systems. Among the first to adopt and spread the use of copper and bronze, the Corded Ware people marked a pivotal shift in European metallurgy. Yet, it is the stone battle axes that stand out as some of their most diagnostic objects.Diametrically aligned around a central perforation, these axe-hammers are finely sculpted, with intricate chiselled details that reveal an aesthetic intent behind their design. Among the most striking are the "boat-shaped" models, their sleek profiles reminiscent of Native American canoes (see lot 80), which are characteristic of the late Neolithic period.André Grisse argued these objects were crafted with geometric precision, based on metric standards. He observed: "These artefacts convey a spiritual and ideological message. Their forms, shaped by geometric and mathematical principles, reflect cultural connections across Europe from the late 6th millennium to the mid-3rd millennium B.C. They bore invisible geometric traces, suggesting their creators' advanced understanding of design and symbolism. Those who carried these objects were likely not just warriors but also scholars or astronomers, connected to earthworks."While their imposing forms may suggest a martial purpose, many clues point also to a ceremonial role. Though nothing can be said with absolute certainty about their use, the limited effectiveness of these axes as cutting tools combined with the significant effort required to produce them makes their function as everyday implements unlikely (though there is debate in this respect). Instead, their depiction on funerary stelae alongside warriors, coupled with the exceptional care in their craftsmanship, suggests they symbolised social status. Some examples may even have been influenced by the earliest copper axes emerging in southeastern Europe during the 5th millennium B.C., reinforcing their symbolic significance.So integral were these artefacts to local cultures that miniature versions were created, possibly for personal adornment or ritual use. In southern Sweden, such miniatures have been found in wetland deposits, likely offered as gifts to the watery realm, while in northern Germany, they appear in mortuary contexts linked to cremation practices. Interestingly, while full-sized battle axes are typically associated with male burials, smaller examples are found in contexts involving women and children, suggesting they may have held talismanic properties. Some miniatures display pounding wear on their edges, unseen on full-sized axes, hinting at their use as mortars, perhaps for grinding materials for rituals. These miniatures might even be precursors to Thor’s hammer pendants of the Viking Age.Though we must be cautious when drawing direct connections, there is a further intriguing link between these ancient stone battle axes and the mythological world of the Viking Age, particularly through language. The people of the Corded Ware Culture are believed to have spoken an early form of the Indo-European language family. The Old Norse word hamarr, which describes Thor’s hammer, carries a dual meaning, both "hammer" and "rock." It's Indo-European roots, signifying "pointed," "sharp," and "stone," connect Thor’s weapon to the same qualities embodied by the stone axes wielded by the Corded Ware peoples. This linguistic link suggests that the hammer, much like the stone axes, was seen not just as a tool, but as an object imbued with power and symbolism deeply tied to the natural and metaphysical world.These stone axes appear to have been passed down through generations, with the evidence shown in their wear patterns and reworked edges, indicating prolonged use and careful maintenance. Some axes show signs of resharpening or re-polishing, suggesting they were prized possessions, preserved and adapted for continued use. Their deposition in high-status burials hints at their role as cherished heirlooms, interred at significant moments - possibly the death of the final owner. Others were placed in liminal spaces, such as riverbanks, bogs, or hilltops, indicating they were offerings to mark transitions or connections between realms both physical and spiritual. In later centuries and millennia, the discovery of these stone battle axes often occurred during ploughing, particularly following storms, when the soil was disturbed and these ancient artefacts emerged. Their striking forms, coupled with this timing, led to their association with "thunderstones", a folkloric belief that such objects were remnants of thunderbolts hurled by gods or supernatural beings. In many European traditions, these axes were thought to possess protective or magical properties, guarding homes from lightning, evil spirits, or even the mischief of trolls and fairies.Originally symbols of power, these axes took on new meaning when they were rediscovered in fields, riverbanks, and other liminal spaces. This connection to celestial or magical power deepened their mystique, transforming them from simple tools into sacred relics. In this way, and in a manner that continues to resonate today, objects such as these have seen many lives, first as weapons, then as relics of forgotten pasts, and now as artefacts that continue to captivate and intrigue, bridging the ancient and the modern.Axelsson, B. & Christensen, P.G.R. (eds.) (2004) The Corded Ware Culture in the Neolithic of Europe: A Social and Economic Approach.Beauvarlet, M. (2000) La Hache de Pierre à Travers le Monde. Paris: Editions Errance.Garrow, D. and Wilkin, N. (2022) The World of Stonehenge. London: British Museum Press.

AFRICAN NEOLITHIC STONE MACEHEAD TENERIAN CULTURE, CENTRAL SAHARA, C. 4TH – 2ND MILLENNIUM B.C. drilled and polished stone, of circular shape, with a central perforation, raised on a bespoke mount 15.6cm diameter Private collection, Belgium, formed late 1960s – present Distinctive stone rings often found in the Sahara are typically associated with the Tenerian culture. Dating to around 6,000 - 5,000 years before the present day, the Tenerian herded, hunted and cultivated crops beside great lakes amidst a savannah environment. These rings, made of stone or occasionally other materials, are thought to have served as decorative or ritualistic objects, although their exact purpose remains a subject of debate among archaeologists.

AFRICAN NEOLITHIC GREEN FELSITE POUNDER TENERIAN CULTURE, CENTRAL SAHARA, C. 4TH – 2ND MILLENNIUM B.C. of narrow cylindrical shape with slightly pointed ends, on a bespoke black metal stand 60cm tall Private collection, Belgium, formed late 1960s – present The Tenerians, a people named for the Ténéré Desert, a stretch of the Sahara in Niger known to Tuareg nomads as a "desert within a desert", were in the region from 5200 B.C. E. to around 2500 B.C.E. This is one of the driest deserts in the world today, but archaeological evidence confirms it hosted at least two flourishing lakeside populations during the Stone Age. The first culture appearing in the area 10 000 years ago were the Kiffians, hunter-fisher-gatherers whose large stature of up to 6 feet proves that food was abundant. The Sahara dried up around 7200 B.C., which caused the Kiffians to disappear. The arid period lasted roughly a millenia, after which the water returned, and with it a new population, this time the Tenerians. Based on skeletal evidence, they curiously seemed to have more in common with people living in the Mediterranean than neighbouring settlers in the Sahara. Around 2500 B.C., the onset widespread desertification of the Sahara ended the settlement in Gobero.

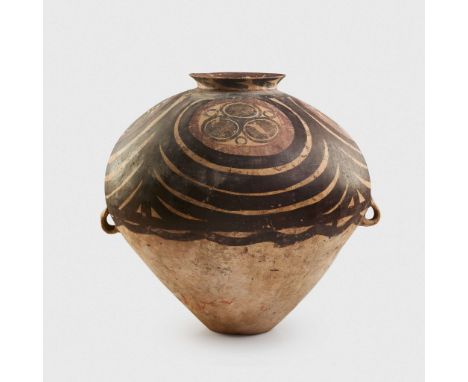

LARGE CHINESE NEOLITHIC "YANGSHAO" VASE CHINA, MAJIAYAO YANGSHAO CULTURE, C. 2300–2000 B.C. painted terracotta, of ovoid form, standing on a flat disc base, with dual miniature strap handles and a short neck with everted rim, the body adorned with thick swirling lines executed in umber pigment 42cm tall Private collection, London, United Kingdom, acquired from the belowPeter Petrou, London The Yangshao culture and the following Majiayao culture (c. 5000–2000 B.C.) were Neolithic civilisations that flourished along the middle reaches of the Yellow River in China. Known for their early advancements in agriculture, these cultures practised millet farming and domestication of animals, supporting settled village life. Yangshao and Majiayao societies are particularly noted for their painted pottery, often featuring geometric and stylised motifs in black and red on buff-coloured earthenware. These ceramics, typically hand-built using coiling techniques, suggest a sophisticated aesthetic sensibility and possible ritual or symbolic significance.

FINE NEOLITHIC POLISHED FLINT AXEHEAD SCANDINAVIA, C. 3500 B.C. flint, the polished stone displaying a mottled grey colour, the cutting edge rounded, raised on a bespoke mount 32.4cm tall Maurice Braham (1938-2022), LondonK. John Hewitt (1919-1994), KentPrivate Collection, UK, 1994-2023Exhibited:An Eye Into the Ancient Past, Forge and Lynch, 3rd - 7th July 2023 “Throughout temperate Europe, the establishment of farming settlements required forest clearance on a substantial scale. These pioneers had to fell trees to create fields for arable crops and to provide timber for houses. In this new world the stone axe came to have huge significance. This simple tool form was prevalent across the continent. While functionally useful for all types of woodworking, stone axes appear to have been much more than essential, well-used tools. Many were completely polished to a shine after being roughly shaped. This process takes several hours of hard work using sand, water and a fine-grained polishing stone. Polishing the body of an axe does not improve its functional qualities as a cutting/chopping tool and it is likely that people did this to enhance the appearance of its surface, bringing out the aesthetic qualities of the stone. The stone used to make axes itself seems to have had special significance. It was often quarried from deep within the earth and some sources were possibly venerated through being invested with magical, mythical significance.”Garrow, D. and Wilkin, N. (2022) The World of Stonehenge. London: British Museum Press. p. 39.

AFRICAN NEOLITHIC GRINDING STONE AND PESTLE CENTRAL SAHARA, C. 4TH – 3RD MILLENNIUM B.C. carved sandstone, with a central depression from repeated use, accompanied by an ancient pestle 62 x 40.5 cm Private collection, E.H., Bavaria, Germany, acquired 1980sRupert Wace, London, United KingdomExhibited: 'The Science of Imaginary Solutions', Breese Little, London, 10th June - 17th September 2016 12,000 years ago, global climate shifts redirected Africa's seasonal monsoons northward, bringing rainfall to a vast expanse of the modern Sahara. This transformation led to the formation of lush watersheds spanning from Egypt to Mauritania, attracting diverse animal life and eventually human settlement. The present piece dates to around 6,000 - 5,000 years before the present day, when a people known as the Tenerian herded, hunted and cultivated crops beside great lakes amidst a savannah environment. The rains departed again around 2,500 B.C., and the Green Sahara became a desert once more, with only artefacts such as this grinding stone left to bear witness to the society which had once flourished.

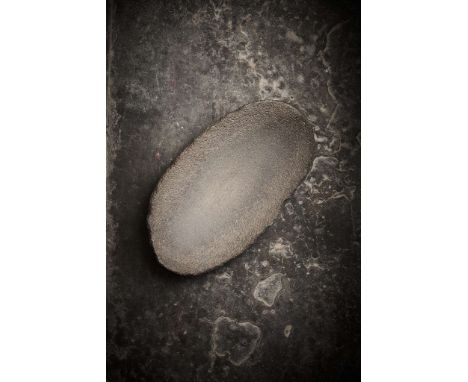

HUGE AFRICAN NEOLITHIC STONE PESTLE CENTRAL SAHARA, C. 4TH – 3RD MILLENNIUM B.C. worked stone, of elliptical form, with sand polished patination, an exceptionally large example 41cm long Private collection, Belgium, formed late 1960s – present The form of this grinding stone is both simple and striking, with its smooth sand polished surface and warm, earthy tones evoking a sense of quiet harmony.

BRITISH NEOLITHIC POLISHED AXEHEAD KENT, UNITED KINGDOM, C. 4TH MILLENNIUM B.C. knapped and polished flint, of mottled grey colour, the cutting edge rounded, the butt tapering to a point, raised on a bespoke mount 25.4cm tall Private collection, London, United Kingdom, acquired on the UK art marketRobert Jay collection, United Kingdom, acquired prior to 1970 Accompanied by a copy of a letter from the British Museum dated to 1970 “Throughout temperate Europe, the establishment of farming settlements required forest clearance on a substantial scale. These pioneers had to fell trees to create fields for arable crops and to provide timber for houses. In this new world the stone axe came to have huge significance. This simple tool form was prevalent across the continent. While functionally useful for all types of woodworking, stone axes appear to have been much more than essential, well-used tools. Many were completely polished to a shine after being roughly shaped. This process takes several hours of hard work using sand, water and a fine-grained polishing stone. Polishing the body of an axe does not improve its functional qualities as a cutting/chopping tool and it is likely that people did this to enhance the appearance of its surface, bringing out the aesthetic qualities of the stone. The stone used to make axes itself seems to have had special significance. It was often quarried from deep within the earth and some sources were possibly venerated through being invested with magical, mythical significance.”Garrow, D. and Wilkin, N. (2022) The World of Stonehenge. London: British Museum Press. p. 39.

Neolithic Period, 6th-4th millennium B.P. Group of three lentoid-section tools each with a worked edge and irregular butt; one marked 'Naphill High Wycombe'. 380 grams total, 66-98 mm (2 1/2 - 3 7/8 in). [3, No Reserve] From the private collection of Kenneth Machin (1936-2020), Buckinghamshire, UK; his collection of antiquities and natural history was formed since 1948; thence by descent.

Neolithic Period, circa 6th-4th millennium B.P. Comprising mostly bifacial and uniface flint and chert arrowheads; probably from the Sahara region of North Africa. See Greenwell, D.F., Artefacts of North Africa, privately published, 2005, for much information. 100 grams total, 24-48 mm (1 - 2 in.). [50, No Reserve] UK gallery, early 2000s.Similar specimens of arrowheads have been found in the Eastern Sahara Region of Abu Tartur Plateau. Most of the arrowheads came from the El Jarar Neolithic, c. 7700-7300 B.P. (c.6500-6100 B.C.). Other parallels occur in the region of Kharga Oasis.

Neolithic Period, circa 6th-4th millennium B.P. or later. Modelled in the round as a figure of a pregnant woman sitting upright with emphasised breast and stomach; mounted on a custom-made stand. Cf. Morris, D., The Art of Ancient Cyprus, Oxford, 1985, figs.107-109, p.119, for similar idols; Various, Idoles, Au commencement etait l’image, A la Reine Margot, 22 Novembre 1990-28 Fevrier 1991, Paris, 1990, fig. 11, for similar; also see Caldwell, Duncan, ‘The Use of Animals in Birth Protection Rituals and Possible Uses of Stone Figurines from the Central Sahel’ in African Arts, UCLA, 2015 Winter issue, vol.48, no.4, Nov., pp.14-25, figs.5, letters A (especially), J-O. 1.47 kg total, 16 cm including stand (6 1/4 in.). [No Reserve] From a collection acquired on the UK art market from various auction houses and collections mostly before 2000. From an important Cambridgeshire estate; thence by descent. Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D’Amato. This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate number no.12334-224207.Most scholars consider these as symbols of the fertility cult and as evidence of the existence of a matriarchal society as a form of organisation of the earliest human society. The people of the Stone Age may have considered figures such as this to represent women and mothers with their life-giving powers, or as depictions of the ancestors.

Neolithic Period, circa 6000 B.P. Possibly from organised archaeology digs: five flint scrapers marked 'BHM' and 'BHS' with dates in the 1980s; two boar tusks marked 'BHM' with dates in the 1980s; quantity of mammal teeth, some marked 'BHM' or 'BHS' 224 grams total, 35-77 mm (1 3/8 - 3 in.). [12, No Reserve] Probably found in the 1980s. From an old large English collection from Lincolnshire. Acquired on the UK art market. From the private collection of an East Anglian, UK, collector.

Neolithic Period, circa 4000-2300 B.P. A complete ground or polished stone axehead sub-ovate in plan, narrower at the butt end with a steep curve to the cutting edge, facetted ovate section with squared off sides. 332 grams, 10.6 cm (4 1/4 in.). [No Reserve] Found Skirpenbeck, East Riding of Yorkshire, UK. Accompanied by a copy of the British Museum's Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) report no.YORYM-3B9FD3.

Neolithic Period, 6th-4th millennium B.P. Roughly spherical with inked '127' legend. 285 grams, 64 mm (2 1/2 in.). [No Reserve] Found Libya. Acquired Phillip Carter, UK. From the private collection of Kenneth Machin (1936-2020), Buckinghamshire, UK; with collection no.N127; his collection of antiquities and natural history was formed since 1948; thence by descent.

Neolithic Period, circa 6000 B.P. Showing the long flake removals which were then made into knives, tools and daggers; marked twice 'SP.' for the findspot 'Spiennes'. 490 grams, 18 cm (7 1/8 in.). [No Reserve] From the world renowned and now world heritage flint factory site of Spiennes, Belgium. From an old Paris collection. Acquired on the European art market. From the private collection of an East Anglian, UK, collector.

Neolithic Period, circa 6000 B.P. Triangular in section with narrow point to each end, grey-white silicious material with some traces of cortex; two inked findspot legend 'SP / I' for 'Spiennes'. 205 grams, 18 cm (7 1/8 in.). [No Reserve] From the world renowned and now world heritage flint factory site of Spiennes, Belgium. From an old Paris collection. Acquired on the European art market. From the private collection of an East Anglian, UK, collector.

Neolithic Period, 4th-2nd millennium B.P. Group of irregular worked stone blades with much cortex. 689 grams total, 7.6-10 cm (3 - 4 in.). [3, No Reserve] Found Fontmaure, France. Acquired in the 1970s-1990s. From the collection of famous UK musician and amateur archaeologist, Victor Brox (1941-2023). From the collection of a South West London, UK, specialist Stone Age collector.

Neolithic Period, circa 6000 B.P. Scaphoid in section with irregular rounded butt and curved edge, polished; old find spot label 'Fontigny Lalbie'. Cf. MacGregor, A. (ed.), Antiquities from Europe and the Near East in the Collection of Lord McAlpine of West Green, Oxford, 1987, item 4.2, for type. 318 grams, 16.2 cm (6 3/8 in.). [No Reserve] Found east of Paris, France. From an old Parisian collection. Acquired on the UK art market. From the private collection of an East Anglian, UK, collector.

Neolithic Period, circa 6th-4th millennium B.P. Comprising mostly bifacial and uniface leaf-shaped and piriform flint and chert arrowheads; probably from the Sahara region of North Africa. See Greenwell, D.F., Artefacts of North Africa, privately published, 2005, for much information. 113 grams total, 23-41 mm (1 - 1 5/8 in.). [50, No Reserve] UK gallery, early 2000s.Similar specimens of arrowheads have been found in the Eastern Sahara Region of Abu Tartur Plateau. Most of the arrowheads came from the El Jarar Neolithic, c. 7700-7300 B.P. (c.6500-6100 B.C.). Other parallels occur in the region of Kharga Oasis.

Neolithic-Early Bronze Age Period, circa 2nd-1st millennium B.P. Plano-convex in section and triangular in plan with short tang and barbs; old inked find spot 'Botley/Hants'. 2.97 grams, 42 mm (1 5/8 in.). [No Reserve] Found Botley, Hampshire, UK. Ex old UK collection. From a Leicestershire, UK, collection.

Neolithic Period, circa 6th-4th millennium B.P. or later. Comprising bird and quadruped figures carved in the round with rounded profile; each mounted on a custom-made stand. Cf. Morris, D., The Art of Ancient Cyprus, Oxford, 1985, fig. 342, p.212, for a similar idol; Various, Idoles, au commencement était l’image – 22 Novembre 1990 – 28 Février 1991, Paris, 1990, fig.11, for a Neolithic sculpture in similar style; Nanoglou, S., ‘Representation of Humans and Animals in Greece and the Balkans during the Earlier Neolithic’ in Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 18, 2008, pp. 1-13, fig.3, nos.2-7, and fig. 6, for similar; also see Caldwell, Duncan, ‘The Use of Animals in Birth Protection Rituals and Possible Uses of Stone Figurines from the Central Sahel’ in African Arts, UCLA, 2015 Winter issue, vol.48, no.4, Nov., pp.14-25, fig.3, letters A, D, F. 1.59 kg total, 9.3-11.7 cm including stand (3 5/8 - 4 5/8 in.). [3, No Reserve] From a collection acquired on the UK art market from various auction houses and collections mostly before 2000. From an important Cambridgeshire estate; thence by descent. Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D’Amato. This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate number no.12338-224208.Most scholars consider these as symbols of the fertility cult and as evidence of early agricultural organisation of the earliest human society. The Stone Age people may have considered figures such as these to represent animals with their life-giving powers.

Neolithic Period, 6th-4th millennium B.P. Rectangular-section bar with rounded sides due to edge-polishing; inked legend 'A24', 'M2'. 300 grams, 15 cm (5 7/8 in.). [No Reserve] Acquired Stephen Murray, UK, 1979. From the private collection of Kenneth Machin (1936-2020), Buckinghamshire, UK; with collection no.N2; his collection of antiquities and natural history was formed since 1948; thence by descent. Accompanied by an original old black and white photograph.

Rugen (Northern Germany), Nordic Neolithic Period, circa 4000-2000 B.P. Knapped and polished in fine honey-coloured flint, trapezoidal in profile and rectangular in section; with rounded butt and slightly convex edge; mounted on a custom-made stand. Cf. MacGregor, A. (ed.), Antiquities from Europe and the Near East in the Collection of Lord McAlpine of West Green, Oxford, 1987, item 4.85, for type. 493 grams total, 17.5 cm (640 grams total, 20.2 cm including stand) (6 7/8 in. (8 in.). (For this specific lot, 5% import VAT is applicable on the hammer price.) From the old German private collection Von Korff family, Germany; inherited by Julian von Korff before 1980, Germany. with Athena Munzen der Antike, Munchen, prior 2004. Inscription on object: Varbelvitz Rügen; inscription on label: 104; inscription on label: 335.

Neolithic Period, 6th-4th millennium B.P. Ovate in profile with carefully worked edge; old collector's label '14 145'. 131 grams, 91 mm (3 1/2 in.). [No Reserve] Found possibly Scarborough area, North Yorkshire, UK. Acquired Oxford, UK, November 2002. From the private collection of Kenneth Machin (1936-2020), Buckinghamshire, UK; with collection no.N145; his collection of antiquities and natural history was formed since 1948; thence by descent.

Neolithic Period, circa 6000 B.P. Triangular in section with narrow square butt and broad curved edge. 125 grams, 18.5 cm (7 1/4 in.). [No Reserve] From the world renowned and now world heritage flint factory site of Spiennes, Belgium. From an old Paris collection. Acquired on the European art market. From the private collection of an East Anglian, UK, collector.

Neolithic Period, 4th-2nd millennium B.P. Each triangular in section with broad butt, some cortex remaining; marked 'Troussencourt' in black ink. 260 grams total, 8.5-10 cm (3 3/8 -- 4 in.). [2, No Reserve] Found Troussencourt, France. Ex Norfolk, UK, private collection of French artefacts acquired prior to 2000. From the collection of a South West London, UK, specialist Stone Age collector.

Neolithic Period, circa 6th-4th millennium B.P. Comprising mostly bifacial and uniface flint and chert arrowheads, including tanged and other types; probably from the Sahara region of North Africa. See Greenwell, D.F., Artefacts of North Africa, privately published, 2005, for much information. 122 grams total, 23-44 mm (1 - 1 3/4 in.). [50, No Reserve] UK gallery, early 2000s.Similar specimens of arrowheads have been found in the Eastern Sahara Region of Abu Tartur Plateau. Most of the arrowheads came from the El Jarar Neolithic, c. 7700-7300 B.P. (c.6500-6100 B.C.). Other parallels occur in the region of Kharga Oasis.

Neolithic Period, 4th-2nd millennium B.P. Triangular in plan with scooped point, cortex to one face. 223 grams, 12.2 cm (4 3/4 in.). [No Reserve] Found Caply, France. Ex Norfolk, UK, private collection of French artefacts acquired prior to 2000. From the collection of a South West London, UK, specialist Stone Age collector.

Neolithic Period, circa 6th-4th millennium B.P. Comprising mostly bifacial and uniface leaf-shaped flint and chert arrowheads; probably from the Sahara region of North Africa. See Greenwell, D.F., Artefacts of North Africa, privately published, 2005, for much information. 207 grams total, 28-46 mm (1 - 1 3/4 in.). [50, No Reserve] UK gallery, early 2000s.Similar specimens of arrowheads have been found in the Eastern Sahara Region of Abu Tartur Plateau. Most of the arrowheads came from the El Jarar Neolithic, c. 7700-7300 B.P. (c.6500-6100 B.C.). Other parallels occur in the region of Kharga Oasis.

Neolithic Period, 6th-4th millennium B.P. Deltoid, leaf-shaped and barbed types each in a collector's archive box with label. 45 grams total, 28-46 mm (1 1/8 - 1 3/4 in.). [3, No Reserve] Found Tillemsi, Mali, West Africa. Acquired Oxford show, UK, July 2010. From the private collection of Kenneth Machin (1936-2020), Buckinghamshire, UK; with collection no.N159a-c; his collection of antiquities and natural history was formed since 1948; thence by descent.

Neolithic Period, circa 1500 B.P. Narrow thick-butted with flared sides, rectangular in section with gently curved edge. Cf. MacGregor, A. (ed.), Antiquities from Europe and the Near East in the Collection of Lord McAlpine of West Green, Oxford, 1987, item 4.12, for type. 455 grams, 16.5 cm (6 1/2 in.). [No Reserve] From an old Danish collection. Acquired on the UK art market. Acquired on the European art market. From the private collection of an East Anglian, UK, specialist collector.

-

3059 item(s)/page