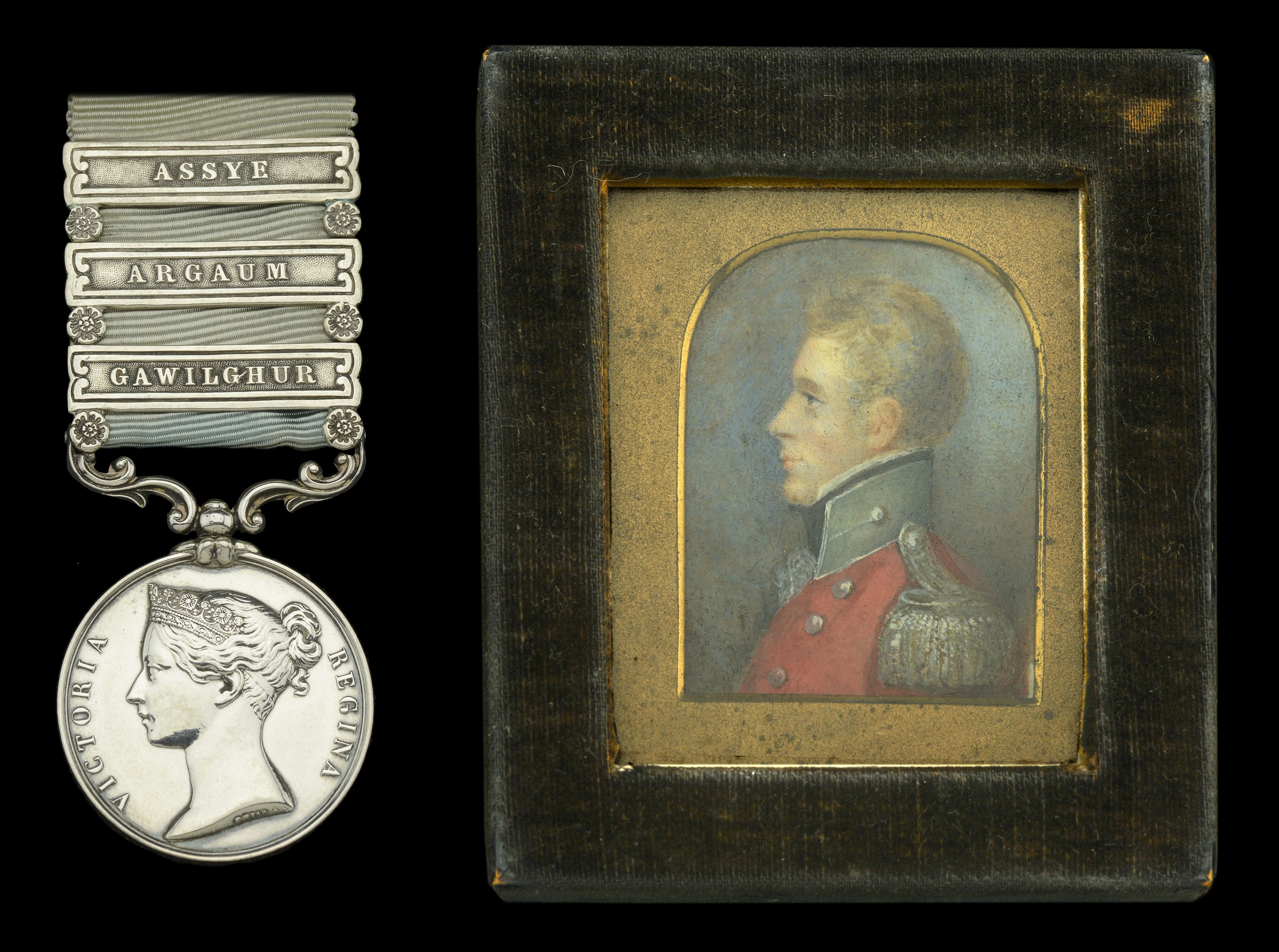

A rare ‘Assye’ three clasp Army of India Medal awarded to Captain J. Smith, 12th Madras Native Infantry, considered by Arthur Wellesley (later the Duke of Wellington) to be his most effective H.E.I.C. Regiment; Smith was wounded at Assaye, probably by cannon fire, which was described by Wellesley as ‘the hottest that has been known in this country’ Army of India 1799-1826, 3 clasps, Assye, Argaum, Gawilghur (Lieut. Jas. Smith, 12th N.I.) short hyphen reverse, officially impressed naming; together with a fine portrait miniature of the recipient, framed and glazed, 52mm x 40mm, the first lightly polished, otherwise very fine and rare (2) £10,000-£14,000 --- Provenance: Sotheby’s, May 2000; Dix Noonan Webb, December 2003. Approximately 149 medals issued with three clasps, 52 with this combination which is unique to the regiment. Arthur Wellesley (later Duke of Wellington) received these same three clasps, of which only 85 were issued for Assaye. Only four of the officers wounded at Assaye lived to claim their medals. James Smith was born in 1784. He was accepted for military service in the H.E.I.C. and appointed to 2nd Battalion, 12th Regiment, Madras Native Infantry. His commissions for the ranks of Ensign and Lieutenant both bear the date 20 July 1801. Lieutenant Smith was wounded at the battle of Assaye on 23 September 1803, the most famous victory won in India by Arthur Wellesley, later the Duke of Wellington. Smith is one of only four officers who were wounded in the battle and lived to claim their medal. Although outnumbered by three to one, Wellesley made an audacious frontal attack on the massed enemy regular battalions which were packed onto a battlefield running north to south, with both their flanks protected by converging rivers. The enemy’s northern flank was additionally anchored on the village of Assye, which had been turned into a heavily fortified stronghold, with heavy guns and infantry protected behind mud walls. Wellesley’s intention was to stay well clear of Assye village and if necessary deal with it after the end of the main battle. Unfortunately, the commander of his right wing mistakenly advanced directly towards it, leading Smith’s regiment into a hurricane of fire which annihilated both the leading H.E.I.C. troops and the 74th Foot. The shattered remnants of the British right were then charged by enemy cavalry. Wellesley’s cavalry retrieved the situation with a countercharge, his battered infantry surged forward and the enemy swung back to a final defensive position arcing westwards from Assye along the northern river bank. As the 2/12th Madras N.I. moved up to take part in the last decisive attack, they were again bombarded by the guns in Assye village. Wellington’s men smashed the enemy infantry and captured all their artillery, at the cost of 27% casualties (compared with 24% at Waterloo). Many years after Waterloo, Wellington was asked to name the best thing he ever did in the way of fighting; he replied “Assye.” The 2/12th M.N.I. had the second highest casualties of all Wellesley’s units engaged at Assye, mostly from enemy artillery fire which was described by Wellesley as “the hottest that has been known in this country”. The battalion lost 212 men and six European officers, including the C.O., Lieutenant-Colonel Macleod, who Wellesley considered to be his best H.E.I.C. battalion commander. Smith recovered from his injuries in time to take part in Wellesley’s next battle, at Argaum on 29 November 1803. The survivors of 2/12th M.N.I. proved somewhat shy, due to their shortage of European officers, their experience of suffering artillery bombardment at Assye and the presence of 1,500 highly professional Arab mercenaries among their adversaries. When the Maratha guns opened fire, two teams of ten bullocks pulling 6-pounder guns bolted, careering back through the infantry and causing several sepoy units including 2/12th M.N.I. to break and flee. Wellesley was close at hand but he could not stop the panic immediately and quietly ordered Smith and the other officers to lead their men into cover. There they re-formed their ranks, when Wellesley led them to their correct positions and ordered them to lie down. After a while, all his battalions began a steady advance through artillery fire towards the enemy line, and destroyed their adversaries, with repeated measured volley fire. Lieutenant Smith participated in the audacious storming in December 1803 of the hilltop fortress of Gawilghur, which was garrisoned by 8,000 men armed with brand-new British Brown Bess muskets, 52 cannon and 150 light swivel guns. He was promoted to Captain in June 1813 but invalided out of the Madras Native Infantry in April 1818, on account of his wounds. Smith’s India medal was issued from the Adjutant General’s Office on 1 April 1852. He had chosen to stay on in India rather than return to Britain and transferred to the 1st Native Veteran Battalion. He is still shown on the strength of this unit in 1856, when he would have been 70 years old. Captain Smith died on 5 June 1859, and is buried in St Mary’s Cemetery, Madras.