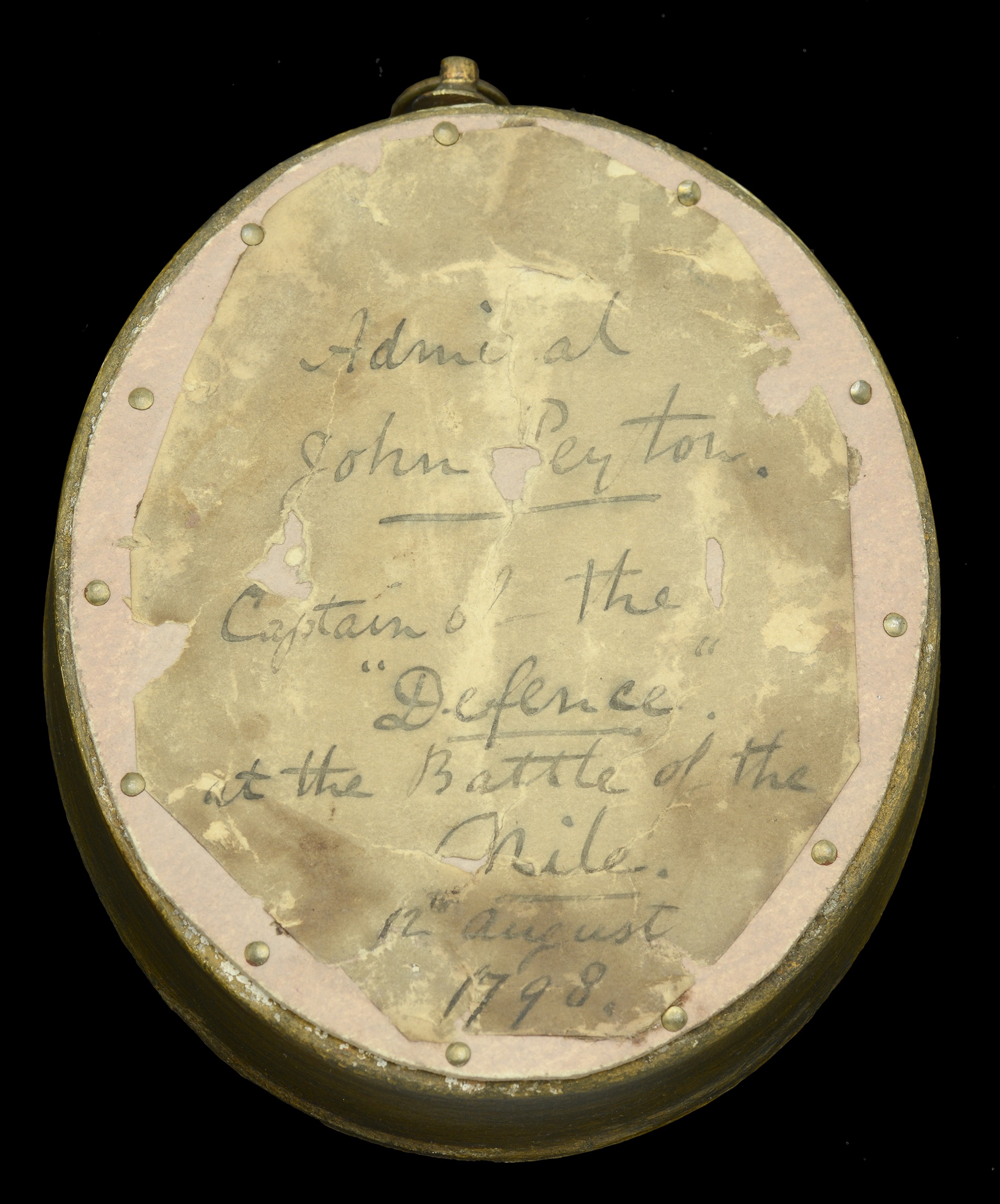

The important Small Naval Gold Medal awarded to Rear-Admiral John Peyton, Royal Navy, one of Nelson’s ‘Band of Brothers’ who commanded H.M.S. Defence ‘with good sense and courage’ at the battle of the Nile Captain’s (Small) Naval Gold Medal 1794-1815, for the Nile, 1 August 1798 (John Peyton Esquire Captain of H.M.S. The Defence on the 1 of August MDCCXCVIII The French Fleet Defeated) in its original gold frame with replacement bevelled glass lunettes, original gold rings and bar suspension, and three-pronged gold ribbon buckle, together with an oval portrait miniature of Captain Peyton, extremely fine and rare (2) £50,000-£70,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Nelson and the Napoleonic Wars, Sotheby’s, October 2005, Lot 140 ‘by direct descent.’ In common with Nelson and the other twelve surviving captains at the Nile, Peyton also received Davison’s Medal in gold. His example was acquired by Captain K. J. Douglas-Morris, R.N., and now resides at the Royal Naval Museum, Portsmouth. John Goodwin Gregory Peyton was born in Ardingly, Sussex in 1752, the son of Joseph and Katherine Peyton and scion of a distinguished naval family. His father rose to the rank of admiral, his paternal grandfather onetime served in the rank of commodore, and three of his brothers also opted for a career in the Senior Service. In one of those strange quirks of fate known to the age of sail, father and son were to fight alongside each other aboard H.M.S. Cumberland at the ‘moonlight battle’ off Cape St. Vincent in January 1780. John is believed to have entered the Royal Navy aboard his father’s ship, H.M.S. Belleisle, in 1766, although his early career is not well documented. Having then gained his Lieutenancy in February 1772, he appears to have remained under his father’s patronage. He was, as stated, serving in Peyton senior’s command the Cumberland at the ‘moonlight battle’ off Cape St. Vincent in January 1780. Peyton junior’s first command was the 10-gun schooner Kite, in which he captured the privateer Fantasque off Dunkirk in March 1782. He was advanced to Commander and, in January of the following year, he was appointed to the command of the 74-gun Carnatic, but it proved to be a short-lived assignment and he was placed on half-pay. In July 1794, Peyton returned to sea with command of the 38-gun Seahorse and spent the next two years on the Irish station. On 29 August 1795, in an action alongside two of her consorts, Seahorse captured the Dutch East Indiaman Cromhout, whilst in May 1796 she was credited taking the French cutter L’Abrille. It appears Peyton was placed back on half-pay about this time, although one source credits him with command of the Ceres on the Mediterranean station. Either way, he was by now a full-fledged Captain, R.N. Nelson’s Band of Brothers In May 1798, Peyton was appointed to the command of the 74-gun Defence and he is said to have shared a coach with Nelson’s wife, Fanny, to Portsmouth, where he was embarked for the Mediterranean in the Admiral’s flagship Vanguard. He surely enjoyed the great man’s company and hospitality over the coming weeks, prior to joining the Defence on station in June. The scene was now set for the epic battle of the Nile, Earl St. Vincent, the C.-in-C. of the Mediterranean, being able to confirm that ten ships, including Defence, were ready to join Nelson’s squadron. In so doing, he told the First Lord of the Admiralty: ‘The whole of these ships are in excellent order, and so well officered, manned and appointed I am confident they will perform everything to be expected of them.’ And so it proved at Aboukir Bay on 1 August 1798, when Nelson’s combined force of 15 ships delivered a stunning victory over the French fleet. For his part, Peyton was credited with commanding the Defence with ‘good sense and courage’. Defence’s log records Nelson’s signal to prepare for battle at 4.00 p.m., when the enemy ships were some nine or ten miles distant, and his next signal at 6.20 p.m. to engage the van. Defence duly took-on the 74-gun Peuple Souverain, already under attack on her other beam by Orion. Firing continued for three hours until 10.00 p.m. when Peuple Souverain cut her cable and drifted away completely mastless. Just five minutes later, Defence manoeuvred to attack the 80-gun Franklin which was already engaged with the Swiftsure. Firing continued until 11.20 p.m. when Franklin hailed Defence to say that she had struck. Both enemy ships suffered heavily, in damage and casualties. For her own part, Defence suffered the loss of her bowsprit and fore topmast and had to replace her main topmast with a jury rig. Given the duration of her ferocious duels and in common with most of her consorts, her human loss was surprisingly light: three seamen and one marine killed, nine seamen and two marines injured; fifteen casualties in all. In writing home to his wife on 13 August, Peyton stated: ‘My ever Dear Love I write you by the Leander who sailed from hence the 6th instant with the Admiral’s dispatches since which we have been busily employed refitting our own ships & prizes. Tomorrow we shall sail & make the best of our way to Gibraltar or Lisbon - & I should hope ultimately to England - at any rate my own Dear Susan, we shall be better situated to hear from each other - no small comfort to both parties - I have my fears you will hear of our action through France before the Leander can probably arrive in England & that in consequence you as well as many others will be kept for some time in a state of anxiety. The more I think of our victory, & its consequences the more I am gratified - & if Bonaparte should fail in his expedition - which we here flatter ourselves that he may - I believe peace not very far distant … The three frigates, Alcmene & Emerald & Bonne Citoyenne that have been looking for us these two months are now coming in - truly mortified they must be - in not meeting us until after the action. I hope to have John dine with me. I think the Captains will get two thousand pounds perhaps more if all our prizes get to England. The Emerald has just passed us & gone to endeavour to free one of our prizes that is aground so that I fear I shall not see John. I must send this to Capt. Capel who leaves us this afternoon. Believe me ever your faithful affectionate husband John Peyton P.S. I find myself a stouter man since the action, another such would make me a fine young fellow. God bless you. The French fleet on the coast of Egypt.’ What made Defence’s role in the battle particularly noteworthy was the fact that most of her crew had been laid low by fever and scurvy. Peyton himself was unwell, writing to Nelson four weeks before the battle that the effect of the weather on his weakening constitution, ‘will make it very unjustifiable in retaining a situation I shall not be equal to.’ Although he somehow managed to take part in the battle, by the end of October 1798 the Earl St. Vincent informed the First Lord of the Admiralty that Peyton was ‘in a deplorable state of health’. He nonetheless took Defence to Gibraltar for repairs, arriving these in mid-September. Following which, in November, he took his passage home in the Colossus. In January 1799, Peyton sent a letter Nelson, explaining that his health was improving. It clearly did the rounds before catching up with the great man in Vanguard in May 1799. But when it did, he responded enthusiastically: ‘It was onl...