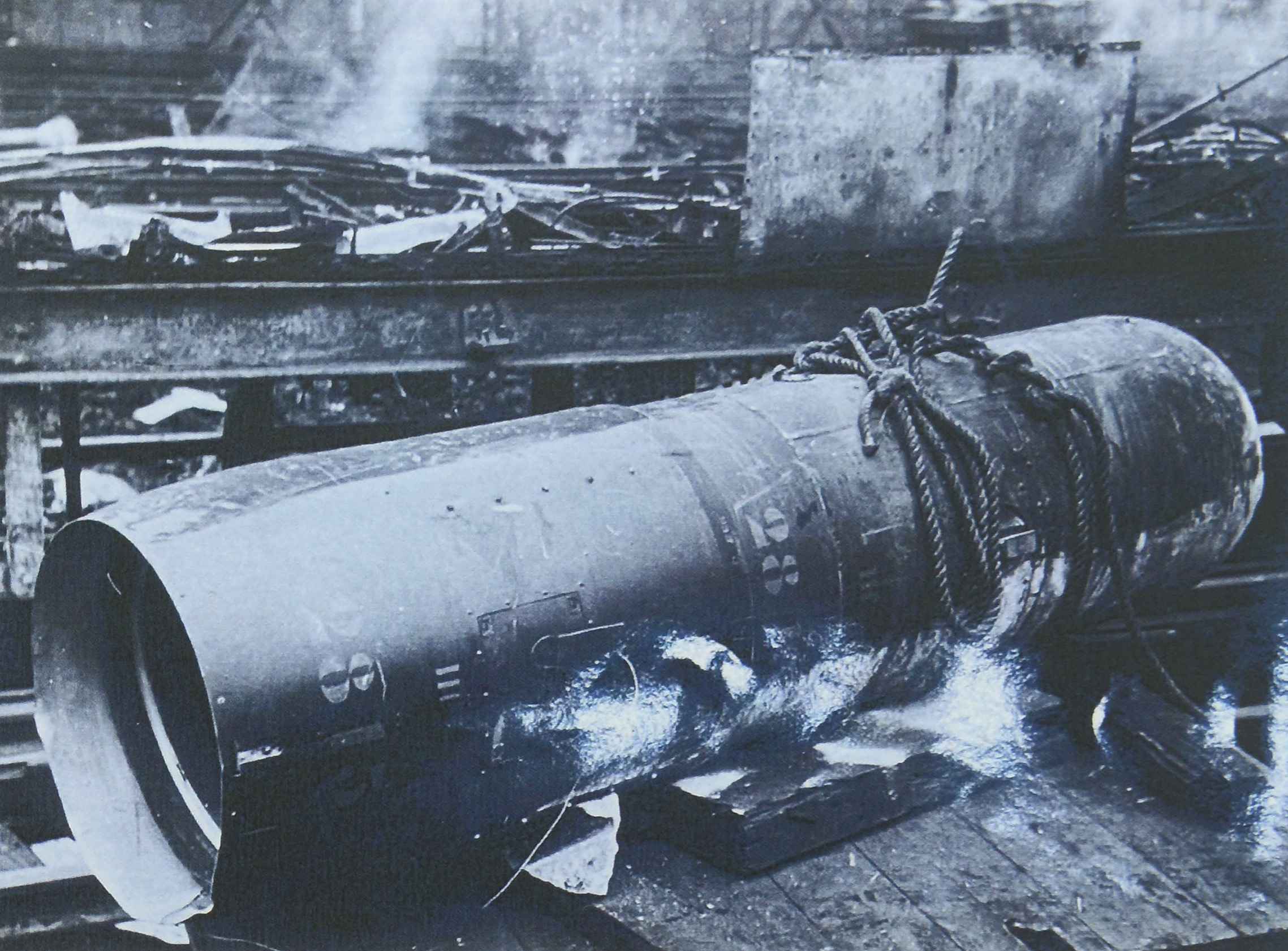

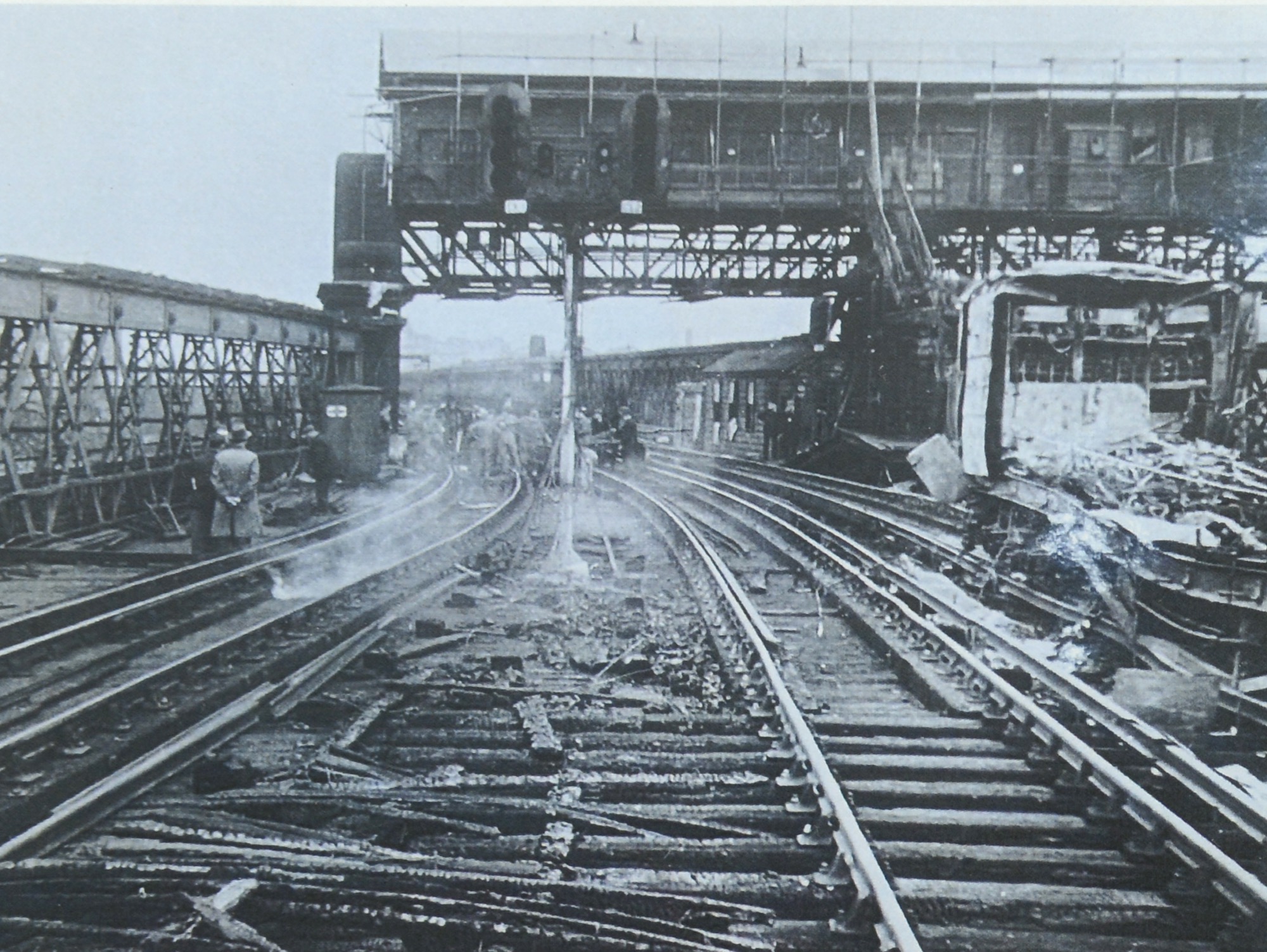

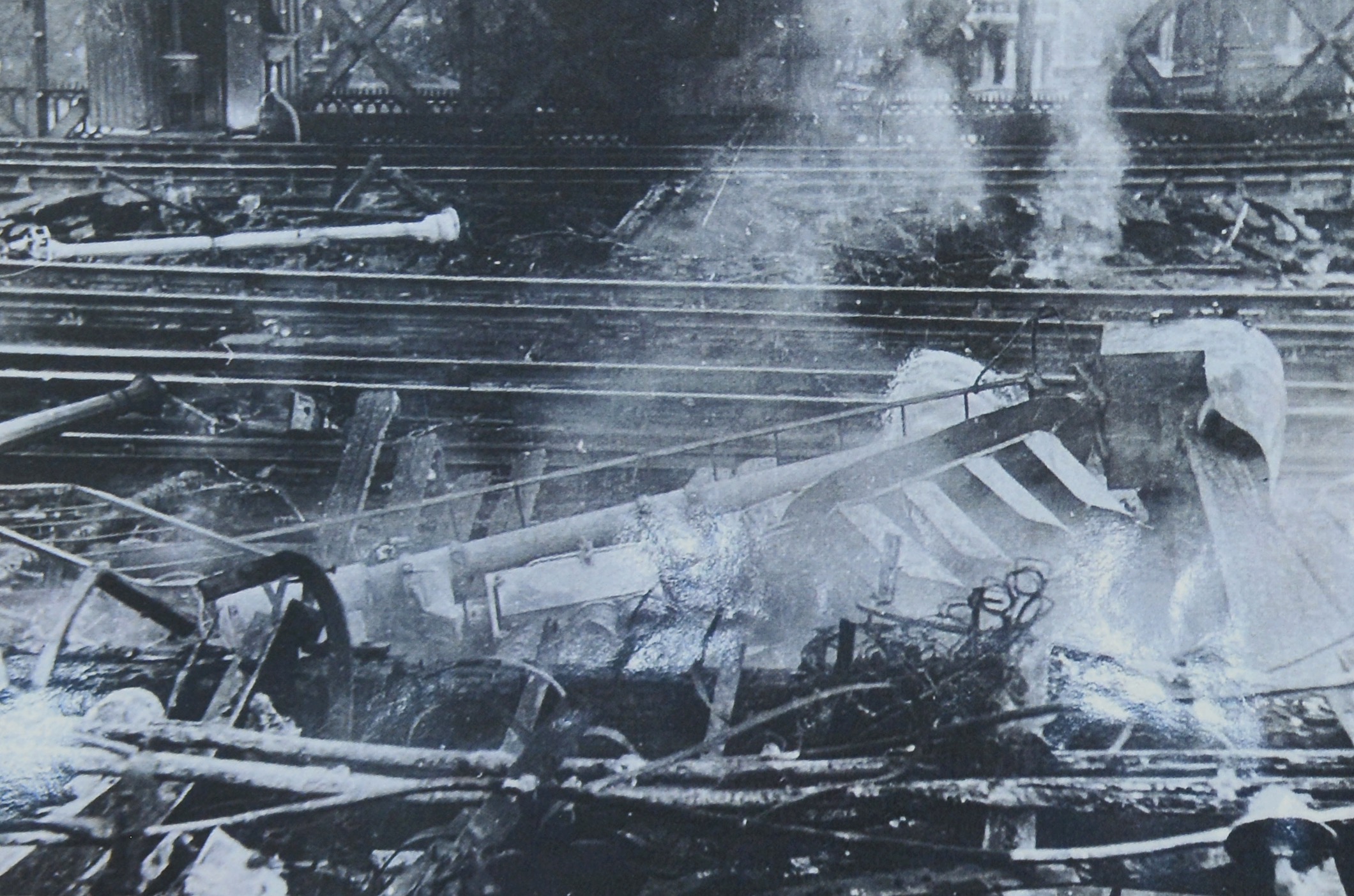

The unique Second War ‘London Blitz’ George Cross, O.B.E., George Medal group of eight awarded to Acting Lieutenant-Commander E. O. ‘Mick’ Gidden, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, ‘the man who saved Charing Cross’ A master of mine disposal operations and the first man to be awarded both the G.C. and G.M., his gallantry in dealing with a parachute mine on Hungerford Bridge, outside Charing Cross Station, in April 1941, was among the great epics of the war: in a six hour operation, in which he was unable to apply a safety device for much of that time, he had to resort to using a hammer and chisel George Cross (Lieut. Ernest Oliver Gidden, G.M., R.N.V.R.); The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, O.B.E. (Military), Officer’s 2nd type breast badge, silver-gilt; George Medal, G.VI.R. (T/Sub-Lieut. Ernest Oliver Gidden, R.N.V.R.); 1939-45 Star; France and Germany Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45; Coronation 1953, mounted as worn, good very fine (8) £100,000-£140,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Just eight men have been awarded the combination of the G.C. and G.M.; the addition of the O.B.E. makes this a unique combination of awards. G.C. London Gazette 9 June 1942: ‘For great gallantry and undaunted devotion to duty.’ The original recommendation states: ‘An unexploded parachute mine dropped on Hungerford Bridge on 17 April 1941. At the time the mine was dropped, some trains and many sleepers were on fire, and Charing Cross Hotel was burning in the background. It was necessary to stop the Underground trains, and evacuate many buildings, including the War Office. Lieutenant Gidden arrived on the Bridge shortly after dawn and found the mine lying across a live electric wire at the foot of the main signal gantry, with the bomb fuse and primer release mechanism facing downwards. The electric current from the rail had melted some of the metal around the bomb fuse and primer release mechanism to such an extent that if the fuse was removed at all, it could only be done by drilling; and, further, before any attempt could be made to arrest the operation of the fuse by the insertion of a “gag”, a lump of molten metal had to be prised from the surface of the fuse itself. Before operations of any kind could be commenced the mine had to be turned to get at the bomb fuse. Turning the mine was in itself likely to detonate it, with disastrous results for railway communications and important buildings. In order, therefore, to be in a position to control the operation with accuracy, Lieutenant Gidden stood at fifty yards only from the mine, while the necessary pull was being exerted from a distance. To appreciate the danger of this case, it should be understood that the fuses in these mines are clockwork and liable to be actuated by the slightest vibration. Lieutenant Gidden had to stop firemen playing water on the sleepers and trains while he got to work, and the burning wood kept giving off loud cracks during the whole of the operations, thus hampering his ability to listen for the clockwork in the fuse running, which is essential for safety. He successfully cleared the surface of the fuse, and inserted a “gag” but the melting had damaged the part in question, and the gag was not a secure fit, and he was aware of the fact. He then attempted to remove the remains of the screw threaded ring (which holds the fuse in place) with a hammer and chisel. At the first blow the clockwork in the fuse started to run. Lieutenant Gidden, who had kept his head close to the fuse, heard the ticking, and made off as best he could, but as it was necessary to jump from sleeper to sleeper, with a ten foot drop below, there was little chance of escape. As it happened the “gag” held, and Lieutenant Gidden returned with a drill. He succeeded in removing the ring, but then found it necessary to prise the fuse out with a chisel. This he successfully did in spite of its dangerous condition. Normally fuses are removed from a distance for fear of some anti-handling device. This operation took six hours to complete. It is considered that this case is in the very highest category of courage and devotion to duty. Lieutenant Gidden has served in the L.I. [Land Incident] Section for over a year, and has dealt with 25 mines. He has successfully commanded the Blue Watch (one third of the Watch) for nine months, and is a most reliable and trustworthy officer.’ O.B.E. London Gazette 28 September 1943: ‘For great bravery and steadfast devotion to duty.’ The original joint recommendation states: ‘This was the second of two acoustic mines dropped at Seasalter, near Whitstable, which had failed to explode and over which a depth charge had been detonated, driving the mine deeper into the mud without countermining it. On this occasion a concrete shaft was used with very satisfactory results. The shaft required no support and remained stationary until the ejector was used, when it sank at a rate of about 6 inches per hour. Work commenced on 31 May 1943, and the mine was exposed on 12 June at a depth of 28 feet over 68 working hours. In order to reduce vibration and noise to a minimum, the last 8 feet were excavated by skip and crane. The mine was found in a vertical position with the tail nuts sheared. This was lifted clear by means of the crane – all unnecessary personnel having been sent to a safe distance. Lieutenant-Commander Gidden, with Leading Seaman Pickett, who volunteered to stay with him, remained at the bottom of the shaft to render the mine safe; Pickett keeping the water, which was coming in under the cutting edge, clear from the two fuses. Whilst uncovering the first fuse, air started to escape, and they were both under the impression that the clock had started. They both started up the iron rungs, knowing full well that if it was the fuse, they could not possibly hope to get clear. After a short interval, they returned and dealt with the fuse – one keep ring had to be drilled off owing to distortion. A flotation bag was then secured to the lifting lug of the mine, which was floated to the surface at high water, towed ashore and steamed out. In the officer’s own words: “I cannot express too highly the manner in which Leading Seaman Pickett worked with me under rather trying circumstances during the rendering safe operations.” It is considered that Lieutenant-Commander E. C. Gidden, G.C., G.M., R.N.V.R., and Leading Seaman F. H. Pickett showed a very high degree of courage and devotion to duty on this occasion and are recommended for awards. G.M. London Gazette 14 January 1941: ‘For gallantry and undaunted devotion to duty.’ The original joint recommendation states: ‘A “D” type mine containing 750lbs. of High Explosive was partly buried in the foundation of a house and in a narrow alley between two houses in Harlesden, in such a position it was not possible to get at the bomb-fuse or electric detonator and primer. Tackles were therefore rigged and the mine dragged out of the ground. It was then lowered into a lorry where attempts to extract the fuse failed, since it had been badly damaged. The electric detonator and primer were now removed and, after reference to the Admiralty, it was decided to sterilise the mine in situ. With the help of an R.E. Bomb Squad, this work was successfully done, with little damage to the surrounding houses. Sub.-Lieutenant Gidden and Able Seaman Lipsham are fortunate in being still alive, since...